Abstract

The Frank–Starling mechanism describes the relationship between stroke volume and preload to the heart, or the volume of blood that is available to the heart—the central blood volume. Understanding the role of the central blood volume for cardiovascular control has been complicated by the fact that a given central blood volume may be associated with markedly different central vascular pressures. The central blood volume varies with posture and, consequently, stroke volume and cardiac output (\( \dot{Q} \)) are affected, but with the increased central blood volume during head-down tilt, stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \) do not increase further indicating that in the supine resting position the heart operates on the plateau of the Frank–Starling curve which, therefore, may be taken as a functional definition of normovolaemia. Since the capacity of the vascular system surpasses the blood volume, orthostatic and environmental stress including bed rest/microgravity, exercise and training, thermal loading, illness, and trauma/haemorrhage is likely to restrict venous return and \( \dot{Q} \). Consequently the cardiovascular responses are determined primarily by their effect on the central blood volume. Thus during environmental stress, flow redistribution becomes dependent on sympathetic activation affecting not only skin and splanchnic blood flow, but also flow to skeletal muscles and the brain. This review addresses the hypothesis that deviations from normovolaemia significantly influence these cardiovascular responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most common clinical evaluation of the circulation is by reporting cardiac frequency (f c) and arterial pressure and it was on the initiative of Cushing (1903) that Riva-Rocci’s (1896) mercury sphygmomanometer was introduced to medicine and forwarded to monitoring arterial pressure in patients during surgery (Bogert and Van Lieshout 2005). Arterial pressure, however, is a regulated variable that is maintained during, e.g. haemorrhage until blood loss exceeds about one litre (Secher et al. 1992; Kinsella and Tuckey 2001; Harms et al. 2003; Campagna and Carter 2003; Cooke et al. 2004). Consequently, arterial pressure is not a reliable index of the intravascular volume (Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al. 1992; Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al. 1996; Pinsky 2002; Boulain et al. 2002) and it is unlikely that normovolaemia can be defined or monitored based on blood pressure or f c (Murrell et al. 2010). It may be considered that when arterial pressure becomes the target of treatment, e.g. with administration of sympathomimetic drugs to restore blood pressure, it is at the expense of regional flow that may include that of the brain (Brassard et al. 2009). Also, the experience is that fluid infusion guided by focus on blood pressure allows for wide variation in the administered volume. In contrast, cardiac output (\( \dot{Q} \)) and especially cardiac stroke volume are sensitive to deviations in preload (Cooke et al. 2004; Secher and Van Lieshout 2005). With the development of techniques like trans-oesophageal and thoracic echocardiography or Doppler (Singer et al. 1989; Toska and Walloe 2002), arterial pulse wave analysis (Harms et al. 1999; Bogert and Van Lieshout 2005) and determination of \( \dot{Q} \) by lithium kinetics (Kurita et al. 1997), several alternatives to the traditional dye dilution and pulmonary catheterisation techniques have become available. These techniques facilitate continuous, and even non-invasive evaluation of not only volume treatment of patients but also the effect of environmental stress on the circulation.

This review focuses on the possibility to define normovolaemia on the basis of the Frank–Starling “law of the heart”. For supine healthy humans, the heart is operating on the plateau of the Frank–Starling curve since further expansion of the central blood volume does neither increase stroke volume nor \( \dot{Q} \) (Harms et al. 2003; Jans et al. 2008; Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2009a, b). The influence of environmental stress including posture, microgravity, heat, exercise, haemorrhage and shock on the central blood volume and its consequence for cardiovascular control are considered in this review.

Starling’s law of the heart for humans

Stroke volume of the heart depends on its preload or on the volume of blood that the heart is provided with, often indicated by its filling pressure (central venous pressure for the right ventricle and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure for the left ventricle), and the relationship between stroke volume and one of the two filling pressures is termed the Frank–Starling mechanism (Zimmer 2002) because of the pioneering studies by Frank (1895) and Starling and colleagues (Patterson and Starling 1914; Patterson et al. 1914). The Frank–Starling mechanism or the “law of the heart” was established in a physiologic canine preparation, but is widely accepted also to apply to the intact organism. This hypothesis has now been evaluated for humans with emphasis on the filling volume of the heart rather than its filling pressures (Harms et al. 2003; Van Lieshout et al. 2005). An increase in central vascular pressures, e.g. with pressure breathing and positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation, is associated with a reduction in central blood volume and \( \dot{Q} \), preload expressed as volume rather than the so-called filling pressure to the heart is relevant for its function. Stroke volume is directly dependent on the volume provided to the heart and hence suitable to estimate cardiac preload in resting humans. A maximal value of stroke volume (and also \( \dot{Q} \) and mixed venous oxygenation) is achieved in the supine position since a further increase in central blood volume by head-down tilt, causing a 7% increase in diastolic filling volume of the heart, is of no consequence, indicating that the maximum value of the Starling curve is reached (Fig. 1c) (Harms et al. 2003; Van Lieshout et al. 2005; Jans et al. 2008). This has been confirmed in supine healthy subjects where a fluid challenge does not increase stroke volume or \( \dot{Q} \). With the extreme 90° head-down tilt position causing a 16% increase in diastolic volume a reduction (12%) in stroke volume is observed (Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2009a, b) indicating that the “right” descending part of the Starling curve is also a physiological phenomenon. Conversely, in the head-up position \( \dot{Q} \) is reduced by more than 1 l min−1 with a concomitant ~10% fall in mixed venous oxygenation reflecting that in upright humans about 70% of the blood volume is positioned below the level of the heart. This orthostatic redistribution takes place since the location in the vascular tree where venous pressure is independent of posture is at the level of the diaphragm (Gauer and Thron 1965; Blomqvist and Stone 1984; Vorstrup et al. 1992; Rowell 1993), while the volume indifference point is somewhat lower, i.e. at the level of the abdomen (Jarvis and Pawelczyk 2009) or the pelvis (Perko et al. 1995).

Oesophageal Doppler aortic flow velocity during goal-directed fluid treatment with illustration of the Starling curve. Actual volume optimization using oesophageal Doppler technique utilizing flow velocity of blood in the descending aorta to estimate stroke volume in a 79-year-old male undergoing surgery. Panels depict the oesophageal Doppler signal and derived values of stroke volume (Q), cardiac output (\( \dot{Q} \)) and cardiac frequency (f c) before optimization (a), after 200 ml of colloid (b) and 400 ml of colloid (c) where the top of the Starling curve was considered to be reached since additional colloid administration did not result in >10% increase in Q. Hereafter colloid infusion was discontinued and additional boluses only administered if Q decreased >10%

Orthostatic stress

Accordingly, from the supine to the erect position, there is a significant displacement of blood to the lower parts of the body with a similar reduction in the central blood volume (Wieling et al. 2002b). The first circulatory event upon assumption of the upright position, either passive or active, is a gravitational displacement of blood away from the thorax filling the veins of dependent regions of the body resulting in a fall in central venous return (Hill 1895; Amberson 1943; Matzen et al. 1991). This shift in blood volume distribution is estimated to 300–800 ml (Blomqvist and Stone 1984) of which 50% takes place within the first few seconds (Brown et al. 1949; De Marées et al. 1973; Kirsch et al. 1980; Smith and Ebert 1990). The central blood volume is further challenged by an estimated 10% or ~500 ml reduction after 5 min and 15–20% or ~750 ml reduction after 10 min (Lundvall et al. 1996) reflecting a shift in the balance between transcapillary fluid loss and gain with distension of dependent veins (Thompson et al. 1928; Tarazi et al. 1970; Hagan et al. 1978; Smith and Ebert 1990). Accordingly, features affecting the central blood volume play a key role in the cardiovascular response to posture (van Heusden et al. 2006).

Since the capacity of the vasculature is larger than the total blood volume, distribution of the blood volume is critical for maintenance of arterial pressure and regional flow. Cardiovascular reflexes controlling sympathetic activation operate to translocate blood volume from the peripheral to the central circulation as a countermeasure to the circulatory effects of gravitational stress, while the veno-arterial reflex (Henriksen and Skagen 1986) elevates total peripheral resistance. However, if humans stand still they may faint, usually with a concomitant decrease in f c and arterial pressure. This reflex, named a vasovagal syncope (Lewis 1932; Van Lieshout et al. 2003b), is activated when central blood volume is reduced by ~30% due to gravitational pooling in the upright posture or by, e.g. haemorrhage or pressure breathing hindering venous return to the heart. The associated reduction in arterial pressure is attributed to a Bezold–Jarisch-like reflex (Jarisch 1941), an eponym for the responses (apnoea, bradycardia and hypotension) demonstrated following intravenous injection of veratrum alkaloids in experimental animals (Aviado and Guevara 2001). The apnoea is mediated through pulmonary vagal afferents and the bradycardia and vasodepression through cardiac vagal afferents that induce vasodilatation in skeletal muscles even at the expense of flow to the brain (Jacobsen et al. 1994; Kinsella and Tuckey 2001; Aviado and Guevara 2001; Campagna and Carter 2003; Mitchell et al. 2009; Hamner et al. 2010).

Time to presyncope during graded orthostatic stress relates to plasma volume normalized for lean body mass (El-Sayed and Hainsworth 1996). This suggests that individuals with a large plasma volume tolerate postural stress better (Wieling et al. 2002b), and supports that venous return is the critical variable during orthostatic stress. A lower orthostatic tolerance in women (Meendering et al. 2005) seems associated with decreased cardiac filling rather than reduced responsiveness of vascular resistance during orthostatic challenges (Fu et al. 2004). Also, in the upright position subjects intolerant to orthostatic stress tend to demonstrate a larger increase in calf filling volume than tolerant subjects (de Chantemele et al. 2004).

The orthostatic fall in venous return affects the central blood volume and thus stroke volume with a decline in \( \dot{Q} \) despite the increase in f c. Furthermore, both middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity and frontal lobe oxygenation decrease in association with the postural reduction in \( \dot{Q} \) (Secher et al. 2008) even though mean arterial pressure increases (Van Lieshout et al. 2001). The postural decrease in middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity (Levine et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 1998; Pott et al. 2000) and frontal lobe oxygenation (Harms et al. 2000) is not accounted for by the associated reduction in the arterial carbon dioxide tension (Immink et al. 2006, 2009) and seems at odds with the concept of cerebral autoregulation, i.e. that cerebral blood flow is relatively constant within a wide range of perfusion pressures (Lassen 1964; Panerai 1998). Accordingly, either central blood volume or more likely \( \dot{Q} \) influences the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation and, therefore, cerebral perfusion both at rest and during exercise (Ide et al. 1998, 1999a; Ogoh et al. 2005a, 2007; Nissen et al. 2009a).

Despite the assault of posture on central blood volume and, in turn, \( \dot{Q} \) and cerebral perfusion, humans can stand erect as long as their circulation is supported by a reflex increase in vasomotor tone. Vasomotor tone limits fluid accumulation in the lower extremities and the increase in total peripheral resistance maintains arterial pressure (Jacobsen et al. 1993; Ray et al. 1993; Ng et al. 1995). As known from soldiers standing in line a vasovagal syncope can be elicited when humans stand still illustrating that there is a need to activate leg muscles to prevent accumulation of blood and fluid in dependent parts of the body in order to maintain orthostatic tolerance (Mayerson and Burch 1940; Madsen et al. 1998; Van Lieshout et al. 2001; Krediet et al. 2006).

Taken together these findings are contrary to the “upright set point” hypothesis for defining a “normal state” of the circulation in humans (Gauer and Thron 1965). Only in the supine position stroke volume, \( \dot{Q} \) and mixed venous oxygenation are maximal for rest (Van Lieshout et al. 2005) at minimal sympathetic activation. The need for activation of cardiovascular reflexes for circulatory postural adaptation, questions whether, in healthy humans, central blood volume is optimised to support the circulation in the upright position. In quadruped animals, the heart is placed at the level of, or below the main part of the circulation and any, even small deviation from that premises, as when the giraffe lowers its head to drink, challenges the circulation since preload to the heart declines because of venous pooling in the neck (Brondum et al. 2009). However, the anatomy of humans is much different since a great part of the musculature is located in the extremities. Consequently, even when humans position themselves on four extremities as quadruped animals, still much of musculature and, hence blood volume is below heart level. Only in the supine and prone positions is preload to the heart comparable with that established for standing quadruped animals. These considerations are consistent with the notion that the blood volume that fosters a maximal stroke volume, \( \dot{Q} \) and mixed venous oxygen saturation corresponds to the central blood volume that manifests in supine humans, i.e. when the heart is at the level of the main part of the vasculature.

Microgravity and bed rest

Bed rest and exposure to microgravity during spaceflight lower the threshold for orthostatic intolerance (Khan et al. 2002; Wieling et al. 2002a; Eckberg 2003). Orthostatic intolerance may develop quickly after even a brief parabolic flight and is associated with an exaggerated fall in total peripheral resistance suggesting that autonomic cardiovascular function alters rapidly after changes in gravity (Schlegel et al. 2001). During spaceflight plasma volume declines within the first day (Hinghofer-Szalkay and White 2008) with a reduction in red cell mass by diminished cell survival via an undefined mechanism and a possibly decreased production of new erythrocytes (Alfrey et al. 1996). In microgravity and with bed rest, the central blood volume is initially increased because of reduced venous pooling in the extremities. The effect of an increased central blood volume is an elevated central venous pressure and through influence from, e.g. increased release of plasma atrial natriuretic peptide and a reduction in plasma antidiuretic hormone (also referred to as vasopressin), total blood volume becomes reduced by renal excretion. According to a model approach of body fluid volume regulation that includes a “set point” regulatory mechanism, the result is what has been addressed to as a new lower set point for total body water (Sawka et al. 2000). The reverse phenomenon is observed in patients with orthostatic hypotension related to sympathetic failure, for whom the improvement during the day by postural renal retention of salt and water (Bradbury and Eggleston 1925) is enforced by an increased blood volume established by head-up sleeping (MacLean and Allen 1940; Cooper and Hainsworth 2008), salt loading (Cooper and Hainsworth 2002) and/or by administration of mineralocorticoids (Sancho et al. 1976; Van Lieshout et al. 2000).

The corollary that cardiovascular and fluid regulatory systems seek the “upright set point” in microgravity constitutes a central hypothesis for studies on acclimation to microgravity. The reduction in blood volume and in stroke volume during spaceflight (Watenpaugh et al. 2001) results in development of orthostatic intolerance upon return to gravity (Buckey et al. 1996). A symptomatic decline in blood volume is also common to humans after prolonged bed rest, and especially hospitalization. Such post bed rest hypovolaemia is attributed to redistribution of the diminished blood volume due to the lack of an effect of gravity (Alfrey et al. 1996).

With stroke volume directly related to central blood volume (Van Lieshout et al. 2005) and left ventricular end-diastolic volume (Levine et al. 2002), the excessive postural fall in stroke volume characterises the reduced orthostatic intolerance related to bed rest that has been attributed to a combination of hypovolaemia and cardiac atrophy (Levine et al. 1997; Mtinangi and Hainsworth 1998; Pawelczyk et al. 2001). Restoration of plasma volume improves the condition (Takenaka et al. 2002), but the observation that only a single day of bed rest reduces sympathetic nerve responses to lower body negative pressure does not support that cardiac “atrophy” is the primary mechanism (Khan et al. 2002). However, it remains debated whether orthostatic intolerance after bed rest is related to insufficient increase in sympathetic discharge in response to a greater postural reduction in stroke volume (Shoemaker et al. 1999; Levine et al. 2002; Khan et al. 2002; Ertl et al. 2002; Kamiya et al. 2003; Eckberg 2003). Whatever the opinion about the benchmark for sympathetic activity, the adaptation of the cardiovascular system to microgravity is a handicap on return to Earth (Wieling et al. 2002a). Hypovolaemia on return to Earth is manifested by a reduced pulse pressure, a lower stroke volume, and a large increase in f c during standing, often with orthostatic intolerance (Buckey et al. 1996; Alfrey et al. 1996; Levine et al. 2002; Gisolf et al. 2005).

Furthermore, both bed rest and microgravity reduce exercise tolerance (Levine et al. 1996; Watenpaugh et al. 2000) and simulated microgravity by prolonged head-down bed rest restricts upright exercise capacity with a reduction in maximal pulmonary oxygen uptake (\( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \)) (Watenpaugh et al. 2000). The finding that \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \) is maintained in the absence of gravity but is reduced immediately on return to Earth is attributed to a reduced blood volume with a lower stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \) (Levine et al. 1996). Yet, submaximal exercise performed daily in space is ineffective to improve orthostatic tolerance (Greenleaf et al. 1989) unless additional exposure to simulated gravity is applied (Watenpaugh et al. 2000; Schneider et al. 2002). Of interest, the reduction in plasma volume as induced by head-down tilt bed rest was restored by a single bout of maximal leg exercise because of greater fluid intake and reduced urine volume during the following 24 h (Convertino et al. 1996). An explanation may be that thirst is provoked by the post-exercise reduction in central blood volume also manifested as a restricted pulmonary diffusion capacity due to a lower amount of red blood cells to receive carbon monoxide (Rasmussen et al. 1992; Hanel et al. 1997).

Heat stress

During heating the vasculature of the skin dilates and is, therefore, increasingly perfused in order to decrease body temperature. Consequently, the central blood volume is reduced with a concomitant decrease in preload (Cai et al. 2000c; Wilson et al. 2007). An upward and leftward displacement of the Starling curve is demonstrated and the ascending part of the curve also becomes steeper (Wilson et al. 2009). Yet, the reduced central blood volume is the likely explanation for the increasing tendency of orthostatic intolerance in heat stressed individuals, since even a minor reduction in central blood volume with the standing position causes large reductions in stroke volume.

Exercise capacity and training

During exercise, an important function of the cardiovascular system is to supply oxygen to active skeletal muscles (Mortensen et al. 2008). Oxygen delivery depends on the transport capacity of the cardio-respiratory system including the volume of blood available. During exercise the major adaptive mechanism is to increase \( \dot{Q} \) and thereby generate a greater perfusion pressure for blood flow which partially restores the blood flow deficit in the active muscles (O’Leary and Joyner 2006). During low intensity exercise, muscle oxygen delivery is prioritised by enhanced vascular conductance and the central blood volume is supported by splanchnic vasoconstriction (Doe et al. 1996; Noble et al. 1997). However, during intense whole-body exercise blood pressure regulation and, therefore, vasoconstriction develops also for working skeletal muscles (Volianitis and Secher 2002).

Ideally, perfusion to exercising skeletal muscles is regulated to match oxygen delivery to demand. Yet, venous oxygenation decreases during maximal exercise to very low levels (<10%) and oxygen delivery becomes dependent on flow. Thus, when \( \dot{Q} \) can no longer support adequate flow, muscle metabolic capacity is affected restricting working muscle as during whole-body exercise (Mortensen et al. 2008). For maintained exercise, perfusion of the brain is of particular importance and accordingly middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity and frontal lobe oxygenation increase during dynamic exercise (Jørgensen et al. 1992; Hellstrøm et al. 1996a; Ide et al. 1999b). However, the capacity to increase cerebral perfusion is attenuated or absent in patients with cardiac insufficiency (Hellstrøm et al. 1996b) or atrial fibrillation (Ide et al. 1999a). Similarly when during cycling the ability to increase \( \dot{Q} \) is limited by cardio-selective β-1 adrenergic blockade in healthy subjects, the increase in middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity (Ide et al. 1998) and frontal lobe oxygenation is equally reduced although mean arterial pressure is maintained (Seifert et al. 2008). Conversely, in patients with heart failure, cerebral blood flow is reduced substantially but increases after cardiac transplantation (Gruhn et al. 2001). Thus, it seems that not only during orthostatic stress but also during exercise, cerebral blood flow participates in overall flow regulation that prioritizes maintained blood pressure at the expense of flow.

Oxygen delivery to the working muscles is a major determinant of \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \) attained during large muscle group exercise (Gonzalez-Alonso and Calbet 2003). Elite endurance athletes possess a high \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \) primarily due to a high \( \dot{Q} \) (Levine 2008) and the blood volume expansion associated with exercise training contributes to improve aerobic power. The main difference between endurance-trained athletes and sedentary individuals is maximal stroke volume (Ekblom and Hermansen 1968). The lowered stroke volume in trained subjects during exercise associated with dehydration appears largely related to an increase in f c (Fritzsche et al. 1999) in response to a reduction in blood volume (Gonzalez-Alonso et al. 2000). During exercise humans lose weight by sweating, but even after weight is restored by drinking, central blood volume remains reduced for many hours following exercise and plasma volume is expanded by further drinking as thirst is maintained (Convertino et al. 1996). Central blood volume is reduced following exercise due to muscle oedema provoked by the combined effects of elevated perfusion pressure and muscle vasodilatation associated with exercise. Also, cutaneous vasodilatation induced by the elevated body temperature contributes to the reduction of central blood volume (Cai et al. 2000c). Even though body temperature normalises and muscle oedema is cleared rapidly after exercise (Clausen et al. 1973; Rasmussen et al. 1992), muscle blood volume remains elevated for several hours (Hanel et al. 1997).

The reduced central blood volume following exercise is reflected in the levels of hormones that regulate fluid balance, including plasma vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) and atrial natriuretic peptide (Hanel et al. 1997). Plasma vasopressin remains elevated while plasma atrial natriuretic peptide is low following exercise and both hormonal changes act to limit urine production resulting in positive fluid balance. As mentioned, during bed rest and space flight, central blood volume is maintained elevated and plasma volume is down-regulated by a reverse hormonal profile to that established following exercise.

An intrinsic problem with whole-body exercise is that, due to vasodilatation, the total capacity of the vasculature outweighs the total blood volume, restricting venous return and thus \( \dot{Q} \) (Andersen and Saltin 1985; Noakes and Ekblom 2008). Restriction of maximal \( \dot{Q} \) implies that oxygen delivery sets a limit to \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \) (Volianitis and Secher 2002; Calbet et al. 2004) with a reduction in regional (muscle, brain) blood flow and, therefore, requires active vasoconstriction (Secher et al. 1977; Savard et al. 1988; Wagner and Secher 2008). Due to the limitation of \( \dot{Q} \) in humans, sympathetic restraint of metabolic vasodilation in the active muscles when standing or exercising is important for arterial pressure regulation. The reflex pressor response is marked by a rise in sympathetic activation with vasoconstriction that in itself limits the ability to improve blood flow to the underperfused contracting muscles or brain (Ide et al. 1998; Van Lieshout et al. 2001; Ogoh et al. 2005a, b; O’Leary and Joyner 2006; Secher et al. 2008). Examples of differentiated regulation of blood flow during whole-body exercise are arm vasoconstriction (Calbet et al. 2007) to an extent that affects oxygen delivery to and utilisation by working skeletal muscles (Volianitis and Secher 2002), reduction of leg blood flow (Pawelczyk et al. 1992), and brain perfusion (Ide et al. 1998; Seifert et al. 2008) when the increase in \( \dot{Q} \) is restricted by cardio-selective β1-adrenergic blockade. Thus, the impaired systemic and skeletal muscle aerobic capacity that precedes fatigue is largely related to the failure of the heart to maintain \( \dot{Q} \) and oxygen delivery to locomotive muscle (Gonzalez-Alonso and Calbet 2003) limiting duration and intensity of exercise (Mortensen et al. 2008).

Exercise training increases blood volume both in healthy subjects and in subjects with orthostatic intolerance (Saltin et al. 1968; Convertino et al. 1980; Greenleaf et al. 1989; Gillen et al. 1991, 1994; Hainsworth 1998; Winker et al. 2005) but whether training-induced plasma volume changes improve athletic performance is debated (Nose and Montain 2008). Expansion of plasma volume usually occurs immediately, but erythrocyte volume expansion takes weeks (Sawka et al. 2000). The plasma volume expansion 1 day following intense exercise is related to a reduced transcapillary filtration rate for albumin suggesting a role for local transcapillary forces in the leg muscle favouring albumin retention in the vascular space after exercise (Haskell et al. 1997; Mack et al. 1998). It is less clear why the red cell volume increases in response to training. Bone marrow is stimulated by erythropoietin released mainly from the kidneys to produce haemoglobin. In that regard the regular finding of reduced arterial oxygen saturation and especially oxygen tension during whole-body exercise may be important (Dempsey and Wagner 1999). However, exposure to high altitude hypoxaemia increases haemoglobin production, but the acute increase in haematocrit is caused by loss of plasma volume (Heinicke et al. 2003). Conversely, end-stage kidney disease is associated with anaemia attributed to low erythropoietin production and erythropoietin administration is integrated in the treatment of these patients. Thus, whole-body exercise, in addition to the exercise-induced hypoxaemia stimulus for erythropoietin production, may stimulate haemoglobin production via sympathetically induced reduction in kidney blood flow (Bodary et al. 1999). In rowers, for whom arterial hypoxaemia is prevalent (Nielsen et al. 2002), approximately 10% of the athletes present with a haematocrit above the ‘doping’ limit of 50% applied to, e.g. cycling (Johansson et al. 2009). The increase in total haemoglobin is an important adaptation to training because \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\;{ \max }}} \) is related to haemoglobin mass (Heinicke et al. 2001). In an apparent paradox, athletes often present somewhat low haemoglobin concentrations (or haematocrit: 44 vs. 46% in untrained) because of the enlarged plasma volume. For athletes plasma and red cell volume may be 61 and 46 ml kg−1, respectively, compared to reference values of 46 and 33 ml kg−1, respectively, for men (Heinicke et al. 2001) and training-induced increase in both plasma volume and red cell mass support preload to the heart.

During exercise, central blood volume contributes to the level of sympatho-excitation established as reflected by f c. For example, at supine rest f c may be 60 beat min−1 and increase to 80 beat min−1 when standing but f c decreases 10 beat min−1 during contraction of the leg muscles in the upright position (Van Lieshout et al. 2001). Muscle contractions increase sympathetic activity but the concomitant enhancement of central blood volume and central venous pressure by the muscle pump elicits a “paradoxical” reduction in sympathetic activity (Ray et al. 1993; Van Lieshout et al. 2001; Secher 2009). Also, during running a smaller central blood volume manifests as a lower central venous pressure and less distension of the atria, as reflected by the plasma level of atrial natriuretic peptide. Furthermore, the lowest f c increase in response to exercise is observed in the supine position (Stenberg et al. 1967). Thus, there is a lower f c during rowing compared to running despite the higher \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2\,{ \max }}} \) established by the larger active muscle mass during rowing (Fig. 2) (Yoshiga and Higuchi 2002). Similarly, the lowering of f c both at rest and during exercise in response to endurance training likely resembles the positional effect on central blood volume (Ogoh et al. 2003).

Lower cardiac frequency during rowing versus running despite a higher oxygen uptake while rowing. Cardiac frequency rowing versus running (*P < 0.05). Modified from Yoshiga and Higuchi (2002)

Blood volume encompasses both red cell mass and plasma volume that change rapidly in response to physical activity. For example, plasma volume is elevated by 20% following short-term training and it decreases during bed rest or space flight (Saltin et al. 1968; Alfrey et al. 1996). The enlargement of plasma volume following training and the reduction in plasma volume when central blood volume remains elevated as during bed rest or space flight suggests that central blood volume rather than total blood volume is the regulated variable (Secher 2009).

The effects of training on a subject’s tolerance to orthostatic stress are less clear with reports indicating improvement, no change or even deterioration (Stegemann 1976; Convertino 1987, 1993). Athletes may develop structural cardiac changes with a steeper slope of the left cardiac pressure–stroke volume relationship indicating a greater reduction in stroke volume for a given decrease in pressure during an orthostatic challenge (Fu et al. 2004). This may be of benefit when exercising but it leads to a considerable reduction in stroke volume during orthostasis (Levine et al. 1991). Ogoh et al. (2003) demonstrated a changed central venous pressure–central blood volume relationship in endurance-trained subjects indicating changes in the mechanical properties of the right heart as well. The implication is that highly fit subjects depend more tightly on the preservation of venous return to maintain \( \dot{Q} \) in the upright body position. The effects of fluid expansion related to endurance training as an intervention to improve orthostatic tolerance appear to be paradoxically offset by cardiac remodelling and reduced effectiveness of baroreceptor control mechanisms. Orthostatic intolerance in deconditioned subjects is related to hypovolaemia and possibly cardiac atrophy (Pawelczyk et al. 2001), and to attenuated carotid baroreflex responsiveness and a larger compliance of the heart in the highly fit. The debate as to the effect of physical training on an individual’s tolerance to orthostatic stress may come to an end by accepting the existence of an ‘optimal level of fitness’, ill-defined as it is, located between the deconditioned and the highly trained state (Van Lieshout 2003). In practice, extreme levels of aerobic fitness associated with orthostatic intolerance are likely to be achieved only by elite military personnel or athletes (Ogoh et al. 2003). The finding that the usual increase in carotid baroreflex responsiveness during head-up tilt is attenuated in endurance-trained subjects provides an explanation for the predisposition to orthostatic hypotension and intolerance in athletes (Ogoh et al. 2003). In moderately fit individuals improvement of the aerobic capacity usually enhances orthostatic tolerance (Carroll et al. 1995; Mtinangi and Hainsworth 1999).

Thus, it seems reasonable to advise exercise training to people who do not easily tolerate standing but to what extent is less certain (Wieling et al. 2002b; Van Lieshout 2003). In addition to the effects of increasing aerobic capacity, resistance training (weight lifting) may reduce venous pooling by increasing muscle tone (Lightfoot et al. 1994; Mayerson and Burch 1940). In contrast, e.g. swimming training does not lead to greater orthostatic tolerance than training for running (Franke et al. 2003). The opposite effects may be seen following prolonged inactivity (Menninger et al. 1969; Convertino et al. 1989). Improving the aerobic capacity of moderately fit individuals increases the plasma volume and is usually associated with improved orthostatic tolerance (Wieling et al. 2002b). The beneficial effect of a training programme in improving orthostatic tolerance was demonstrated in identical twins who fainted during passive tilting. After a 3-week training program applied to one of them, a subsequent head-up tilt-induced faint could be elicited in the untrained twin only (Allen et al. 1945). This observation contrasts to the propensity of highly trained individuals towards a lower tolerance to orthostatic stress than untrained people, paraphrased as ‘trained men can run, but they cannot stand’ (Greenleaf et al. 1981).

Haemorrhage

The changes in f c and arterial pressure during a progressive reduction in central blood volume by haemorrhage illustrate how central blood volume can be followed in humans (Jacobsen and Secher 1992; Secher et al. 1992). The first documented observations are from World War II in air raid casualties with hypovolaemic shock (Grant and Reeve 1941; McMichael 1944), in volunteers bleeding large amounts (Shenkin et al. 1944), and in patients with serious haemorrhagic shock where the finding of a low f c was unexpected (Van Lieshout and Secher 1999; Kinsella and Tuckey 2001).

During the first stage of haemorrhage, corresponding to a reduction of the blood volume by approximately 15%, a modest increase in f c (<100 beats min−1) and total peripheral resistance compensate for the blood loss with maintenance of a near normal arterial pressure (Schadt and Ludbrook 1991; Jacobsen and Secher 1992). The second stage is marked by a decrease in f c, total peripheral resistance and arterial pressure when the central blood volume becomes reduced by ~30% attributed to a Bezold–Jarisch-like reflex (Jarisch 1941; Murray et al. 1968; Matzen et al. 1991; Esler et al. 1995). When blood loss continues, arterial pressure declines further and tachycardia (>120 beats min−1) becomes manifest; this third stage probably reflects the transition to irreversible shock (Jacobsen and Secher 1992; Kirkman and Little 1994). Sander-Jensen et al. (1986) showed in patients with serious blood loss f c was initially low and increased only after repletion of the volume deficit. This observation underscores that the traditional teaching that haemorrhage is diagnosed easily by a reflex tachycardia and a low arterial pressure is not legitimate.

Values for arterial pressure and f c are easily obtained and continue to serve as monitors for volume treatment in hypotension and shock. This approach seems physiological when considering that arterial pressure is the principal cardiovascular variable monitored by the body through the baroreceptors (Eckberg and Sleight 1992) but may be less relevant in old healthy subjects (Secher and Van Lieshout 2010) in whom f c changes during post-exercise hypotension are insignificant (Murrell et al. 2010). Cardiac stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \) still play a subservient role although it is flow, not pressure that the tissues are in need of (Nichols and O’Rourke 2005). For instance, in patients with septic shock, artificially increasing mean arterial pressure beyond ~65 mmHg does not improve established variables of tissue perfusion (LeDoux et al. 2000). Nevertheless, a value for mean arterial pressure rather than flow continues to be the major target of treatment with fluids and inotropic agents.

Thus the traditional description of hypovolaemic shock (Wiggers 1950; Chien 1967) contrasts to the non-linear relationships of f c and arterial pressure with a volume loss in both humans (Murray et al. 1968; Sander-Jensen et al. 1986) and animals (Rasmussen et al. 1999; Krantz et al. 2000).

Normovolaemia

According to studies in humans at rest and under different types of environmental stress, a functional definition of ‘normovolaemia’ would be by its ability to provide the heart with an optimal central blood volume, i.e. that cardiac pumping capacity is not limited by its preload (Ejlersen et al. 1995b). Thus, hypovolaemia may be characterised by a reduced preload to the heart, i.e. with stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \) becoming dependent on central blood volume. A sensitive and specific measure of early reductions in central blood volume is stroke volume (Cooke et al. 2004) and documenting that stroke volume increases with volume loading is taken to imply that a patient is preload-responsive (Pinsky 2002). In contrast, the intravascular volume may be expanded beyond the volume that can provide for a ‘maximal’ \( \dot{Q} \) at rest. By interpolation between hypo- and hypervolaemia, functional normovolaemia is the point in the cardiac preload–output relationship at which \( \dot{Q} \) does not increase further under circumstances where venous return is unimpeded (Van Lieshout et al. 2005).

Applications to clinical medicine

In clinical medicine central blood volume rather than the total blood volume is to be balanced between hypovolaemic shock and development of pulmonary and peripheral oedema. With the functional perspective of normovolaemia, volume treatment should be provided to secure a resting \( \dot{Q} \) that is not preload limited (Secher and Van Lieshout 2005; Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2007a). There are several reservations in providing volume treatment primarily on the basis of cardiovascular variables.

Physiology is concerned with regulation of cardiovascular variables such as mean arterial pressure, regional blood flow (Vatner 1974; Cooke et al. 2004), vascular resistance and blood volume (Ludbrook 1969), whereas clinical practise focuses on the information that such variables provide for treatment. Therefore, it is problematic that no single variable responds exclusively to a reduced central blood volume (Secher and Van Lieshout 2005). Under various conditions, normal or average circulatory values do not apply to the individual, or to a given disease or condition.

Acute blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients may reduce cerebral perfusion (Immink et al. 2004). Conversely, even a normal mean arterial pressure may induce cerebral hyperperfusion and death in a patient with acute liver failure (Larsen et al. 1995). Comparable to what happens to skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise, regional flow is allowed to increase for as long as it does not affect mean arterial pressure. However, when \( \dot{Q} \) is restricted and challenges mean arterial pressure, flow to exercising muscles, and to the brain, becomes limited (Secher et al. 2008). Under these conditions monitoring of cerebral blood flow is indicated, but continuous measurement of regional blood flow is not regularly available in the clinical setting. Since cerebral blood flow is related to \( \dot{Q} \) independent from arterial pressure, maintaining \( \dot{Q} \) may prevent undetected cerebral hypoperfusion and monitoring of \( \dot{Q} \) under these circumstances becomes mandatory.

The most common volume assessment still used in intensive care units is central venous pressure, together with pulmonary artery wedge pressure. Most often stroke volume or \( \dot{Q} \) are related to either central venous pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressures or pulmonary artery wedge pressure (Levine et al. 1991; Perhonen et al. 2001). The implicit assumption is that pressure changes in parallel with the central blood volume, but in some cases the reverse may be true. In patients there may be no correlation between stroke volume and central pressures while there is a tight relation between stroke volume and the filling of the heart (Thys et al. 1987; Levine et al. 1991). Recent studies have questioned the correlation between these estimates of ventricular filling pressures and \( \dot{Q} \); healthy volunteers demonstrate a lack of correlation between initial central venous pressure and pulmonary artery wedge pressure and both end-diastolic ventricular volume and stroke volume (Kumar et al. 2004). Also with changes in central blood volume as elicited by tilting head-up and head-down, stroke volume changed with the thoracic fluid content rather than with the central vascular pressures (Van Lieshout et al. 2005). These findings question central venous pressure and pulmonary artery wedge pressure as useful predictors of ventricular preload (Godje et al. 1998) and support the notion that the function of the heart relates to its volume rather than to its so-called filling pressures (Van Lieshout et al. 2005).

The classical method for determination of central blood volume is by a dye dilution estimate of \( \dot{Q} \) with a concomitant determination of transit time (Sjöstrand 1953). The tight coupling of \( \dot{Q} \) with the filling volume of the heart, even in situations where a relationship between \( \dot{Q} \) and central filling pressures is lost, illustrates the feasibility of evaluation of cardiac preload by echocardiography (Thys et al. 1987). As most methods for measuring central blood volume require extensive apparatus, it is useful to apply Ohm’s law to the body and evaluate volume directly by electrical impedance plethysmography (Nijboer 1970; Cai et al. 2000a, b; Krediet et al. 2006). Such assessment of the volume of the body, and more specifically of the volume contained within the central vessels and the heart, is readily available (Fig. 3).

Left ventricular stroke volume and thoracic electrical admittance. Relationship between cardiac output and preload (thoracic admittance) during progressive central hypovolaemia by passive head-up tilt at 60° in 9 healthy humans (1 female) with median age 29 (range 22–39) years, height 183 (170–191) cm, and weight 75 (68–82) kg. The supine and tilt positions are indicated with the duration in the head-up position in minutes. Values are mean ± SE. Modified from Van Lieshout et al. (2005)

Although estimates of changes in central blood volume are available, it is a problem that the optimal filling of the heart remains unknown. In surgery, preservation of the central blood volume is challenged by factors such as bleeding, capillary leakage and evaporation. Also anaesthetic drugs applied in spinal and epi(peri)dural anaesthesia reduce the central blood volume (Arndt et al. 1985) as a result of redistribution. Establishment of normovolaemia to maintain an optimal oxygen delivery to organs is intuitively rational. Whereas standard monitoring of f c and arterial pressure does not detect a reduction of central blood volume, which is a prerequisite of circulatory support, flow-related variables reflect the intravascular volume status in surgical patients, facilitating correct fluid therapy. However, fluid overload is also detrimental leading to compromised cardiac-, lung-, and gastrointestinal function (Holte et al. 2002) affecting post-operative outcome (Lobo et al. 2002; Brandstrup et al. 2003; Nisanevich et al. 2005). Consequently, to avoid both hypovolaemia and fluid overload in surgical patients, fluid therapy with individual maximization of flow-related haemodynamic variables, so-called goal-directed therapy, has been introduced (Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2007b).

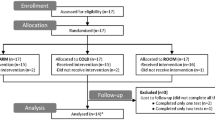

With individualized goal-directed therapy, a volume (usually a synthetic colloid) is administered in amounts of 200–250 ml challenges. If stroke volume increases ≥10% the patient is regarded as being on the ascending part of the cardiac function curve (Fig. 1) and then the fluid challenge is repeated until the ceiling of the cardiac function curve is reached. Hereafter stroke volume is monitored and a fluid challenge is only provided if a 10% decrease in stroke volume is observed (Grocott et al. 2005; Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2007a). In this context, peri-operative maximization of cardiac stroke volume by means of fluid therapy improves post-operative outcome after femoral fractures (Sinclair et al. 1997; Venn et al. 2002), general (Gan et al. 2002; Pearse et al. 2005), cardiac (Mythen and Webb 1995; McKendry et al. 2004) and major bowel surgery (Conway et al. 2002; Wakeling et al. 2005; Noblett et al. 2006). Goal-directed therapy reduces gastro-intestinal complications, overall complication and hospital stay (Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2007a). The reduction of complications especially in the splanchnic system may be explained by improved perfusion of its vasculature (Mythen and Webb 1995) and possibly by avoidance of intestinal oedema.

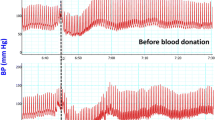

The implication of individualised goal-directed fluid therapy is that when a maximal stroke volume is established for patients, cardiac preload has become comparable to that of supine healthy subjects (Jans et al. 2008; Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2009a, b). In this context it is demonstrated that although the overall volume that has to be administered to obtain a maximal stroke volume is minor, patients with a larger deficit of clinical relevance may be identified (Jenstrup et al. 1995; Ejlersen et al. 1995a; Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2009a, b). Use of the goal-directed approach is, however, challenged by the invasiveness of traditional monitoring modalities of stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \). The thermodilution technique is the accepted clinical method of estimating \( \dot{Q} \), but it is discontinuous and requires the presence of a pulmonary artery catheter for as long as monitoring of \( \dot{Q} \) is needed. However, advances in the area potentially provides more readily available and less invasive modalities that may encourage more widespread use of the goal-directed approach (Bundgaard-Nielsen et al. 2007b; Kehlet and Bundgaard-Nielsen 2009). Ultrasound (Sugawara et al. 2003; Van Lieshout et al. 2003a) and pulse wave analysis or stroke volume modelling either non-invasively from finger pressure (Eeftinck Schattenkerk et al. 2009) or from intra-arterial pressure (Antonutto et al. 1994; Harms et al. 1999; Nissen et al. 2009b) posses the potential to track beat-to-beat changes in stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \) in humans as initiated by postural fluid shifts (Fig. 4) (Harms et al. 1999). The use of variation in stroke volume and pulse pressure as markers of fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients is promising but so far the evidence of favoured outcome with use of these variables is limited (Lopes et al. 2007).

Non-invasive stroke volume tracking during orthostatic variations in central blood volume. Tracking of a thermodilution estimate of stroke volume (Q, solid line) by Modelflow stroke volume (broken line) from non-invasive finger blood pressure (Finapres); averaged values obtained in 10 healthy subjects. Central blood volume was manipulated by passive (tilt) and active (standing) changes in body position. Direction of changes in stroke volume is reciprocal to body position (head-up vs. supine). Modified from Harms et al. (1999)

Conclusions

Environmental stress including posture, microgravity, heat, exercise haemorrhage and shock affect preload to the heart and, consequently, stroke volume and \( \dot{Q} \). Both at rest and during exercise, \( \dot{Q} \) is preload dependent in upright humans, which results in sympathetic activation with an increase in f c and total peripheral resistance. Under these conditions, primarily flow to the splanchnic area is reduced but also flow to the brain and working skeletal muscles become affected, especially during whole-body exercise. Conversely, the plateau of the Starling curve for the heart is reached when humans are supine and that observation may be applied to define normovolaemia of consequence for monitoring of volume treatment of patients, and, as exemplified in this review, to explain at least part of the cardiovascular response to environmental stress.

References

Alfrey CP, Udden MM, Leach-Huntoon C, Driscoll T, Pickett MH (1996) Control of red blood cell mass in spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81:98–104

Allen SC, Taylor CL, Hall VE (1945) A study of orthostatic insufficiency by the tiltboard method. Am J Physiol 143:11–20

Amberson WR (1943) Physiologic adjustments to the standing posture. Bull School Med 27:127–145

Andersen P, Saltin B (1985) Maximal perfusion of skeletal muscle in man. J Physiol 366:233–249

Antonutto G, Girardis M, Tuniz D, Petri E, Capelli C (1994) Assessment of cardiac output from noninvasive determination of arterial pressure profile in subjects at rest. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 69:183–188

Arndt JO, Hock A, Stanton-Hicks M, Stuhmeier KD (1985) Peridural anesthesia and the distribution of blood in supine humans. Anesthesiology 63:616–623

Aviado DM, Guevara AD (2001) The Bezold-Jarisch reflex. A historical perspective of cardiopulmonary reflexes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 940:48–58

Blomqvist CG, Stone HL (1984). Cardiovascular adjustments to gravitational stress. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM (eds) Handbook of physiology—section 2: the cardiovascular system. Peripheral circulation and organ blood flow, vol 3. American Physiological Society, Washington D.C., pp 1025–1063

Bodary PF, Pate RR, Wu QF, McMillan GS (1999) Effects of acute exercise on plasma erythropoietin levels in trained runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31:543–546

Bogert LW, Van Lieshout JJ (2005) Non-invasive pulsatile arterial pressure and stroke volume changes from the human finger. Exp Physiol 90:437–446

Boulain T, Achard JM, Teboul JL, Richard C, Perrotin D, Ginies G (2002) Changes in BP induced by passive leg raising predict response to fluid loading in critically ill patients. Chest 121:1245–1252

Bradbury S, Eggleston C (1925) Postural hypotension: a report of three cases. Am Heart J 1:73–86

Brandstrup B, Tonnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R, Hjortso E, Ording H, Lindorff-Larsen K, Rasmussen MS, Lanng C, Wallin L, Iversen LH, Gramkow CS, Okholm M, Blemmer T, Svendsen PE, Rottensten HH, Thage B, Riis J, Jeppesen IS, Teilum D, Christensen AM, Graungaard B, Pott F (2003) Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens: a randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg 238:641–648

Brassard P, Seifert T, Secher NH (2009) Is cerebral oxygenation negatively affected by infusion of norepinephrine in healthy subjects? Br J Anaesth 102(6):800–805

Brondum ET, Hasenkam JM, Secher NH, Bertelsen MF, Grondahl C, Petersen KK, Buhl R, Aalkjaer C, Baandrup U, Nygaard H, Smerup M, Stegmann F, Sloth E, Oestergaard KH, Nissen P, Runge M, Pitsillides K, Wang T (2009) Jugular venous pooling during lowering of the head affects blood pressure of the anesthetised giraffe. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297(4):R1058–R1065

Brown GE, Wood EH, Lambert EH (1949) Effects of tetra-ethyl-ammonium chloride on the cardiovascular reactions in man to changes in posture and exposure to centrifuged force. J Appl Physiol 2:117–132

Buckey JCJ, Lane LD, Levine BD, Watenpaugh DE, Wright SJ, Moore WE, Gaffney FA, Blomqvist CG (1996) Orthostatic intolerance after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81:7–18

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Holte K, Secher NH, Kehlet H (2007a) Monitoring of perioperative fluid administration by individualized goal-directed therapy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 51:331–340

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Ruhnau B, Secher NH, Kehlet H (2007b) Flow-related techniques for preoperative goal-directed fluid optimization. Br J Anaesth 98:38–44

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Jorgensen CC, Secher NH, Kehlet H (2009a) Functional intravascular volume deficit in patients before surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand [Epub ahead of print]

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Sorensen H, Dalsgaard M, Rasmussen P, Secher NH (2009b) Relationship between stroke volume, cardiac output and filling of the heart during tilt. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53:1324–1328

Cai Y, Boesen M, Stromstad M, Secher NH (2000a) An electrical admittance based index of thoracic intracellular water during head-up tilt in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 83:356–362

Cai Y, Holm S, Jenstrup M, Strømstad M, Eigtved A, Warberg J, Hojgaard L, Friberg L, Secher NH (2000b) Electrical admittance for filling of the heart during lower body negative pressure in humans. J Appl Physiol 89:1569–1576

Cai Y, Jenstrup M, Ide K, Perko M, Secher NH (2000c) Influence of temperature on the distribution of blood in humans as assessed by electrical impedance. Eur J Appl Physiol 81:443–448

Calbet JA, Jensen-Urstad M, van Hall G, Holmberg HC, Rosdahl H, Saltin B (2004) Maximal muscular vascular conductances during whole body upright exercise in humans. J Physiol 558:319–331

Calbet JA, Gonzalez-Alonso J, Helge JW, Sondergaard H, Munch-Andersen T, Boushel R, Saltin B (2007) Cardiac output and leg and arm blood flow during incremental exercise to exhaustion on the cycle ergometer. J Appl Physiol 103:969–978

Campagna JA, Carter C (2003) Clinical relevance of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Anesthesiology 98:1250–1260

Carroll JF, Convertino VA, Pollock ML, Graves JE, Lowenthal DT (1995) Effect of 6 months of exercise training on cardiovascular responses to head-up tilt in the elderly. Clin Physiol 15:13–25

Chien S (1967) Role of the sympathetic nervous system in hemorrhage. Physiol Rev 47:214–288

Clausen JP, Klausen K, Rasmussen B, Trap-Jensen J (1973) Central and peripheral circulatory changes after training of the arms or legs. Am J Physiol 225:675–682

Convertino VA (1987) Aerobic fitness, endurance training, and orthostatic intolerance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 15:223–259

Convertino VA (1993) Endurance exercise training: conditions of enhanced hemodynamic responses and tolerance to LBNP. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25:705–712

Convertino VA, Brock PJ, Keil LC, Bernauer EM, Greenleaf JE (1980) Exercise training-induced hypervolemia: role of plasma albumin, renin, and vasopressin. J Appl Physiol 48:665–669

Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Stein SL (1989) Changes in size and compliance of the calf after 30 days of simulated microgravity. J Appl Physiol 66:1509–1512

Convertino VA, Engelke KA, Ludwig DA, Doerr DF (1996) Restoration of plasma volume after 16 days of head-down tilt induced by a single bout of maximal exercise. Am J Physiol 270:R3–R10

Conway DH, Mayall R, Abdul-Latif MS, Gilligan S, Tackaberry C (2002) Randomised controlled trial investigating the influence of intravenous fluid titration using oesophageal Doppler monitoring during bowel surgery. Anaesthesia 57:845–849

Cooke WH, Ryan KL, Convertino VA (2004) Lower body negative pressure as a model to study progression to acute hemorrhagic shock in humans. J Appl Physiol 96:1249–1261

Cooper VL, Hainsworth R (2002) Effects of dietary salt on orthostatic tolerance, blood pressure and baroreceptor sensitivity in patients with syncope. Clin Auton Res 12:236–241

Cooper VL, Hainsworth R (2008) Head-up sleeping improves orthostatic tolerance in patients with syncope. Clin Auton Res 18:318–324

Cushing H (1903) On routine determination of arterial tension in operating room and clinic. Boston Med Surg J 148:250–256

de Chantemele B, Pascaud L, Custaud MA, Capri A, Louisy F, Ferretti G, Gharib C, Arbeille P (2004) Calf venous volume during stand-test after a 90-day bed-rest study with or without exercise countermeasure. J Physiol 561:611–622

De Marées H, Kunitsch G, Barbey K (1973) Untersuchung über Kreislaufregulation während der orthostatischen Anpassungsphase. Basic Res Cardiol 69:462–478

Dempsey JA, Wagner PD (1999) Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia. J Appl Physiol 87:1997–2006

Doe CP, Drinkhill MJ, Myers DS, Self DA, Hainsworth R (1996) Reflex vascular responses to abdominal venous distension in the anesthetized dog. Am J Physiol 271:H1049–H1056

Eckberg DL (2003) Bursting into space: alterations of sympathetic control by space travel. Acta Physiol Scand 177:299–311

Eckberg DL, Sleight P (1992) Human baroreflexes in health and disease. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, Van Lieshout JJ, Van den Meiracker AH, Wesseling KR, Blanc S, Wieling W, Van Montfrans GA, Settels JJ, Wesseling KH, Westerhof BE (2009) Nexfin noninvasive continuous blood pressure validated against Riva-Rocci/Korotkoff. Am J Hypertens 22:378–383

Ejlersen E, Skak C, Moller K, Pott F, Secher NH (1995a) Central cardiovascular responses to surgical incision at a maximal mixed venous oxygen saturation. Transplant Proc 27:3500

Ejlersen E, Skak C, Moller K, Pott F, Secher NH (1995b) Central cardiovascular variables at a maximal mixed venous oxygen saturation in severe hepatic failure. Transplant Proc 27:3506–3507

Ekblom B, Hermansen L (1968) Cardiac output in athletes. J Appl Physiol 25:619–625

El-Sayed H, Hainsworth R (1996) Salt supplement increases plasma volume and orthostatic tolerance in patients with unexplained syncope. Heart 75:134–140

Ertl AC, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Levine BD, Robertson RM, Cox JF, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA, Ray CA, Buckey JC Jr, Lane LD, Shiavi R, Gaffney FA, Costa F, Holt C, Blomqvist CG, Eckberg DL, Baisch FJ, Robertson D (2002) Human muscle sympathetic nerve activity and plasma noradrenaline kinetics in space. J Physiol 538:321–329

Esler M, Ludbrook J, Wallin BG (1995) Cardiovascular regulation: afferent autonomic pathways and mechanisms. In: Secher NH, Pawelczyk JA, Ludbrook J (eds) Blood loss and shock. Edward Arnold, London, pp 77–91

Frank O (1895) Dynamik des Herzmuskels. Zeitschrift für Biologie 32:370–437

Franke WD, Mills KK, Lee K, Hernandez JP (2003) Training mode does not affect orthostatic tolerance in chronically exercising subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 89:263–270

Fritzsche RG, Switzer TW, Hodgkinson BJ, Coyle EF (1999) Stroke volume decline during prolonged exercise is influenced by the increase in heart rate. J Appl Physiol 86:799–805

Fu Q, Arbab-Zadeh A, Perhonen MA, Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD (2004) Hemodynamics of orthostatic intolerance: implications for gender differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286:H449–H457

Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, El Moalem H, Robertson KM, Moretti E, Dwane P, Glass PS (2002) Goal-directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology 97:820–826

Gauer OH, Thron HL (1965). Postural changes in the circulation. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM (eds) Handbook of physiology. Section 2: the cardiovascular system. The peripheral circulation, vol 3. American Physiological Society, Washington DC, pp 2409–2439

Gillen CM, Lee R, Mack GW, Tomaselli CM, Nishiyasu T, Nadel ER (1991) Plasma volume expansion in humans after a single intense exercise protocol. J Appl Physiol 71:1914–1920

Gillen CM, Nishiyasu T, Langhans G, Weseman C, Mack GW, Nadel ER (1994) Cardiovascular and renal function during exercise-induced blood volume expansion in men. J Appl Physiol 76:2602–2610

Gisolf J, Immink RV, Van Lieshout JJ, Stok WJ, Karemaker JM (2005) Orthostatic blood pressure control before and after space flight, determined by time-domain baroreflex method. J Appl Physiol 98:1682–1690

Godje O, Peyerl M, Seebauer T, Lamm P, Mair H, Reichart B (1998) Central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and intrathoracic blood volumes as preload indicators in cardiac surgery patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 13:533–539

Gonzalez-Alonso J, Calbet JA (2003) Reductions in systemic and skeletal muscle blood flow and oxygen delivery limit maximal aerobic capacity in humans. Circulation 107:824–830

Gonzalez-Alonso J, Mora-Rodriguez R, Coyle EF (2000) Stroke volume during exercise: interaction of environment and hydration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278:H321–H330

Grant RT, Reeve EB (1941) Clinical observations on air-raid casualties. Br Med J 2(4208):293–297; 329–332

Greenleaf JE, Sciaraffa D, Shvartz E, Keil LC, Brock PJ (1981) Exercise training hypotension: implications for plasma volume, renin, and vasopressin. J Appl Physiol 51:298–305

Greenleaf JE, Wade CE, Leftheriotis G (1989) Orthostatic responses following 30-day bed rest deconditioning with isotonic and isokinetic exercise training. Aviat Space Environ Med 60:537–542

Grocott MP, Mythen MG, Gan TJ (2005) Perioperative fluid management and clinical outcomes in adults. Anesth Analg 100:1093–1106

Gruhn N, Larsen FS, Boesgaard S, Knudsen GM, Mortensen SA, Thomsen G, Aldershvile J (2001) Cerebral blood flow in patients with chronic heart failure before and after heart transplantation. Stroke 32:2530–2533

Hagan RD, Diaz FJ, Horvath SM (1978) Plasma volume changes with movement to supine and standing positions. J Appl Physiol 45:414–418

Hainsworth R (1998) Exercise training in orthostatic intolerance. QJM 91:715–717

Hamner JW, Tan CO, Lee K, Cohen MA, Taylor JA (2010) Sympathetic control of the cerebral vasculature in humans. Stroke 41:102–109

Hanel B, Teunissen I, Rabøl A, Warberg J, Secher NH (1997) Restricted postexercise pulmonary diffusion capacity and central blood volume depletion. J Appl Physiol 83:11–17

Harms MPM, Wesseling KH, Pott F, Jenstrup M, Van Goudoever J, Secher NH, Van Lieshout JJ (1999) Continuous stroke volume monitoring by modelling flow from non-invasive measurement of arterial pressure in humans under orthostatic stress. Clin Sci 97:291–301

Harms MPM, Colier WNJM, Wieling W, Lenders JW, Secher NH, Van Lieshout JJ (2000) Orthostatic tolerance, cerebral oxygenation, and blood velocity in humans with sympathetic failure. Stroke 31:1608–1614

Harms MPM, Van Lieshout JJ, Jenstrup M, Pott F, Secher NH (2003) Postural effects on cardiac output and mixed venous oxygen saturation in humans. Exp Physiol 88(5):611–616

Haskell A, Nadel ER, Stachenfeld NS, Nagashima K, Mack GW (1997) Transcapillary escape rate of albumin in humans during exercise-induced hypervolemia. J Appl Physiol 83:407–413

Heinicke K, Wolfarth B, Winchenbach P, Biermann B, Schmid A, Huber G, Friedmann B, Schmidt W (2001) Blood volume and hemoglobin mass in elite athletes of different disciplines. Int J Sports Med 22:504–512

Heinicke K, Prommer N, Cajigal J, Viola T, Behn C, Schmidt W (2003) Long-term exposure to intermittent hypoxia results in increased hemoglobin mass, reduced plasma volume, and elevated erythropoietin plasma levels in man. Eur J Appl Physiol 88:535–543

Hellstrøm G, Fischer-Colbrie W, Wahlgren NG, Jøgestrand T (1996a) Carotid artery blood flow and middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity during physical exercise. J Appl Physiol 81:413–418

Hellstrøm G, Magnusson G, Wahlgren NG, Saltin B (1996b) Physical exercise may impair cerebral perfusion in patients with chronic heart failure. Cardiol Elderly 4:191–194

Henriksen O, Skagen K (1986). Local and central sympathetic vasoconstrictor reflexes in human limbs during orthostatic stress. In: Christensen NJ, Henriksen O, Lassen NA (eds) The sympathoadrenal system. Physiology and pathophysiology. Alfred Benzon symposium, no 23. Munksgaard, Copenhagen, pp 83–94

Hill L (1895) The influence of the force of gravity on the circulation of the blood. J Physiol 18:15–53

Hinghofer-Szalkay H, White RJ (2008) Physiological considerations of human performance in space. In: Taylor NAS, Groeller H (eds) Physiological bases of human performance during work and exercise. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp 459–470

Holte K, Sharrock NE, Kehlet H (2002) Pathophysiology and clinical implications of perioperative fluid excess. Br J Anaesth 89:622–632

Ide K, Pott F, Van Lieshout JJ, Secher NH (1998) Middle cerebral artery blood velocity depends on cardiac output during exercise with a large muscle mass. Acta Physiol Scand 162:13–20

Ide K, Gulløv AL, Pott F, Van Lieshout JJ, Koefoed BG, Petersen P, Secher NH (1999a) Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise in patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Physiol 19:284–289

Ide K, Horn A, Secher NH (1999b) Cerebral metabolic response to submaximal exercise. J Appl Physiol 87:1604–1608

Immink RV, van den Born BJ, Van Montfrans GA, Koopmans RP, Karemaker JM, Van Lieshout JJ (2004) Impaired cerebral autoregulation in patients with malignant hypertension. Circulation 110:2241–2245

Immink RV, Secher NH, Roos CM, Pott F, Madsen PL, Van Lieshout JJ (2006) The postural reduction in middle cerebral artery blood velocity is not explained by PaCO2. Eur J Appl Physiol 96:609–614

Immink RV, Truijen J, Secher NH, Van Lieshout JJ (2009) Transient influence of end-tidal carbon dioxide tension on the postural restraint in cerebral perfusion. J Appl Physiol PMID:19574504

Jacobsen J, Secher NH (1992) Heart rate during haemorrhagic shock. Clin Physiol 12:659–666

Jacobsen TN, Morgan BJ, Scherrer U, Vissing SF, Lange RA, Johnson N, Ring WS, Rahko PS, Hanson P, Victor RG (1993) Relative contributions of cardiopulmonary and sinoaortic baroreflexes in causing sympathetic activation in the human skeletal muscle circulation during orthostatic stress. Circ Res 73:367–378

Jacobsen T, Jost CMT, Converse RL Jr, Victor RG (1994) Cardiovascular sensors: the bradycardic phase in hypovolaemic shock. In: Secher NH, Pawelczyk JA, Ludbrook J (eds) Blood loss and shock. Edward Arnold, London, pp 47–59

Jans O, Tollund C, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Selmer C, Warberg J, Secher NH (2008) Goal-directed fluid therapy: stroke volume optimisation and cardiac dimensions in supine healthy humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 52:536–540

Jarisch A (1941) Vagovasale Synkope. Z Kreisl Forsch 23:267–279

Jarvis SS, Pawelczyk JA (2009) Identification of the human electrical impedance indifferent point: a surrogate for the volume indifferent point? Eur J Appl Physiol 107:473–480

Jenstrup M, Ejlersen E, Mogensen T, Secher NH (1995) A maximal central venous oxygen saturation (SvO2max) for the surgical patient. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 107:29–32

Johansson PI, Ullum H, Jensen K, Secher NH (2009) A retrospective cohort study of blood hemoglobin levels in blood donors and competitive rowers. Scand J Med Sci Sports 19:92–95

Jørgensen LG, Perko M, Hanel B, Schroeder TV, Secher NH (1992) Middle cerebral artery flow velocity and blood flow during exercise and muscle ischemia in humans. J Appl Physiol 72:1123–1132

Kamiya A, Michikami D, Fu Q, Iwase S, Hayano J, Kawada T, Mano T, Sunagawa K (2003) Pathophysiology of orthostatic hypotension after bed rest: paradoxical sympathetic withdrawal. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285:H1158–H1167

Kehlet H, Bundgaard-Nielsen M (2009) Goal-directed perioperative fluid management: why, when, and how? Anesthesiology 110:453–455

Khan MH, Kunselman AR, Leuenberger UA, Davidson WR Jr, Ray CA, Gray KS, Hogeman CS, Sinoway LI (2002) Attenuated sympathetic nerve responses after 24 hours of bed rest. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H2210–H2215

Kinsella SM, Tuckey JP (2001) Perioperative bradycardia and asystole: relationship to vasovagal syncope and the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Br J Anaesth 86:859–868

Kirkman E, Little RA (1994) Cardiovascular regulation during hypovolaemic shock—central integration. In: Secher NH, Pawelczyk JA, Ludbrook J (eds) Blood loss and shock. Edward Arnold, London, pp 61–75

Kirsch KA, Merke J, Hinghofer-Szalkay H (1980) Fluid volume distribution during changes in body posture in man. Pflügers Arch 383:195–201

Krantz T, Cai Y, Lauritsen T, Warberg J, Secher NH (2000) Accurate monitoring of blood loss: thoracic electrical impedance during hemorrhage in the pig. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 44:598–604

Krediet CT, Van Lieshout JJ, Bogert LW, Immink RV, Kim YS, Wieling W (2006) Leg crossing improves orthostatic tolerance in healthy subjects: a placebo-controlled crossover study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291:H1768–H1772

Kumar A, Anel R, Bunnell E, Habet K, Zanotti S, Marshall S, Neumann A, Ali A, Cheang M, Kavinsky C, Parrillo JE (2004) Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and central venous pressure fail to predict ventricular filling volume, cardiac performance, or the response to volume infusion in normal subjects. Crit Care Med 32:691–699

Kurita T, Morita K, Kato S, Kikura M, Horie M, Ikeda K (1997) Comparison of the accuracy of the lithium dilution technique with the thermodilution technique for measurement of cardiac output. Br J Anaesth 79:770–775

Larsen FS, Pott F, Hansen BA, Ejlersen E, Knudsen GM, Clemmesen JD, Secher NH (1995) Transcranial Doppler sonography may predict brain death in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Transplant Proc 27:3510–3511

Lassen NA (1964) Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res 15:201–204

LeDoux D, Astiz ME, Carpati CM, Rackow EC (2000) Effects of perfusion pressure on tissue perfusion in septic shock. Crit Care Med 28:2729–2732

Levine BD (2008) \( \dot{V}{\text{O}}_{{ 2{ \max }}} \): what do we know, and what do we still need to know? J Physiol 586:25–34

Levine BD, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Friedman DB, Blomqvist CG (1991) Left ventricular pressure-volume and Frank-Starling relations in endurance athletes. Implications for orthostatic tolerance and exercise performance. Circulation 84:1016–1023

Levine BD, Giller CA, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG (1994) Cerebral versus systemic hemodynamics during graded orthostatic stress in humans. Circulation 90:298–306

Levine BD, Lane LD, Watenpaugh DE, Gaffney FA, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG (1996) Maximal exercise performance after adaptation to microgravity. J Appl Physiol 81:686–694

Levine BD, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA (1997) Cardiac atrophy after bed-rest deconditioning: a nonneural mechanism for orthostatic intolerance. Circulation 96:517–525

Levine BD, Pawelczyk JA, Ertl AC, Cox JF, Zuckerman JH, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Ray CA, Smith ML, Iwase S, Saito M, Sugiyama Y, Mano T, Zhang R, Iwasaki K, Lane LD, Buckey JC Jr, Cooke WH, Baisch FJ, Eckberg DL, Blomqvist CG (2002) Human muscle sympathetic neural and haemodynamic responses to tilt following spaceflight. J Physiol 538:331–340

Lewis T (1932) Vasovagal syncope and the carotid sinus mechanism with comments on Gowers’s and Nothnagel’s syndrome. Br Med J 1(3723):873–876

Lichtwarck-Aschoff M, Zeravik J, Pfeiffer UJ (1992) Intrathoracic blood volume accurately reflects circulatory volume status in critically ill patients with mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 18:142–147

Lichtwarck-Aschoff M, Beale R, Pfeiffer UJ (1996) Central venous pressure, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure, intrathoracic blood volume, and right ventricular end-diastolic volume as indicators of cardiac preload. J Crit Care 11:180–188

Lightfoot JT, Torok DJ, Journell TW, Turner MJ, Claytor RP (1994) Resistance training increases lower body negative pressure tolerance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26:1003–1011

Lobo DN, Bostock KA, Neal KR, Perkins AC, Rowlands BJ, Allison SP (2002) Effect of salt and water balance on recovery of gastrointestinal function after elective colonic resection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359:1812–1818

Lopes MR, Oliveira MA, Pereira VO, Lemos IP, Auler JO Jr, Michard F (2007) Goal-directed fluid management based on pulse pressure variation monitoring during high-risk surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 11:R100

Ludbrook J (1969) The interaction between vasoconstriction and autoregulation after hemorrhage. Surg Clin N Am 49:637–641

Lundvall J, Bjerkhoel P, Quittenbaum S, Lindgren P (1996) Rapid plasma volume decline upon quiet standing reflects large filtration capacity in dependent limbs. Acta Physiol Scand 158:161–167

Mack GW, Yang R, Hargens AR, Nagashima K, Haskell A (1998) Influence of hydrostatic pressure gradients on regulation of plasma volume after exercise. J Appl Physiol 85:667–675

MacLean AR, Allen EV (1940) Orthostatic hypotension and orthostatic tachycardia; treatment with the “head-up” bed. JAMA 115:2162–2167

Madsen P, Svendsen LB, Jorgensen LG, Matzen S, Jansen E, Secher NH (1998) Tolerance to head-up tilt and suspension with elevated legs. Aviat Space Environ Med 69:781–784

Matzen S, Perko G, Groth S, Friedman DB, Secher NH (1991) Blood volume distribution during head-up tilt induced central hypovolaemia in man. Clin Physiol 11:411–422

Mayerson HS, Burch GE (1940) Relationships of tissue (subcutaneous and intramuscular) and venous pressures to syncope induced in man by gravity. Am J Physiol 128:258–269

McKendry M, McGloin H, Saberi D, Caudwell L, Brady AR, Singer M (2004) Randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of a nurse delivered, flow monitored protocol for optimisation of circulatory status after cardiac surgery. BMJ 329:258

McMichael J (1944) Clinical aspects of shock. JAMA 124:275–281

Meendering JR, Torgrimson BN, Houghton BL, Halliwill JR, Minson CT (2005) Menstrual cycle and sex affect hemodynamic responses to combined orthostatic and heat stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289:H631–H642

Menninger RP, Mains RC, Zechman FW, Piemme TA (1969) Effect of two weeks bed rest on venous pooling in the lower limbs. Aerosp Med 40:1323–1326

Mitchell DA, Lambert G, Secher NH, Raven PB, Van Lieshout JJ, Esler MD (2009) Jugular venous overflow of noradrenaline from the brain: a neurochemical indicator of cerebrovascular sympathetic nerve activity in humans. J Physiol 587:2589–2597

Mortensen SP, Damsgaard R, Dawson EA, Secher NH, Gonzalez-Alonso J (2008) Restrictions in systemic and locomotor skeletal muscle perfusion, oxygen supply and VO2 during high-intensity whole-body exercise in humans. J Physiol 586:2621–2635

Mtinangi BL, Hainsworth R (1998) Early effects of oral salt on plasma volume, orthostatic tolerance, and baroreceptor sensitivity in patients with syncope. Clin Auton Res 8:231–235

Mtinangi BL, Hainsworth R (1999) Effects of moderate exercise training on plasma volume, baroreceptor sensitivity and orthostatic tolerance in healthy subjects. Exp Physiol 84:121–130

Murray RH, Thompson LJ, Bowers JA, Albright CD (1968) Hemodynamic effects of graded hypovolemia and vasodepressor syncope induced by lower body negative pressure. Am Heart J 76:799–811

Murrell C, Cotter JD, Georg K, Shave R, Wilson L, Thomas K, Williams MJA, Lowe T, Ainslie PN (2010) Influence of age on syncope following prolonged exercise; differential responses but similar orthostatic intolerance. J Physiol 588

Mythen MG, Webb AR (1995) Perioperative plasma volume expansion reduces the incidence of gut mucosal hypoperfusion during cardiac surgery. Arch Surg 130:423–429

Ng AV, Johnson DG, Callister R, Seals DR (1995) Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during postural change in healthy young and older adults. Clin Auton Res 5:57–60

Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF (2005) McDonald’s blood flow in arteries: theoretical, experimental and clinical principles, 5th edn. Hodder Arnold, London

Nielsen HB, Bredmose PP, Stromstad M, Volianitis S, Quistorff B, Secher NH (2002) Bicarbonate attenuates arterial desaturation during maximal exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 93:724–731

Nijboer J (1970) Electrical impedance plethysmography. Thomas, Springfield

Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I (2005) Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intraabdominal surgery. Anesthesiology 103:25–32

Nissen P, Van Lieshout JJ, Nielsen HB, Secher NH (2009a) Frontal lobe oxygenation is maintained during hypotension following propofol-fentanyl anesthesia. AANA J 77:271–276

Nissen P, Van Lieshout JJ, Novovic S, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Secher NH (2009b) Techniques of cardiac output measurement during liver transplantation: arterial pulse wave versus thermodilution. Liver Transpl 15:287–291

Noakes TD, Ekblom B (2008) Human performance and maximal aerobic power. In: Taylor NAS, Groeller H (eds) Physiological bases of human performance during work and exercise. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp 177–190

Noble BJ, Drinkhill MJ, Myers DS, Hainsworth R (1997) Mechanisms responsible for changes in abdominal vascular volume during sympathetic nerve stimulation in anaesthetized dogs. Exp Physiol 82:925–934

Noblett SE, Snowden CP, Shenton BK, Horgan AF (2006) Randomized clinical trial assessing the effect of Doppler-optimized fluid management on outcome after elective colorectal resection. Br J Surg 93:1069–1076