Abstract

Purpose

The objective is to evaluate the association between various indicators of alcohol consumption and the degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet among the Spanish adult population.

Methods

A cross-sectional study including 44,834 participants ≥ 15 years of age from the 2017 National Health Survey and the 2020 European Health Survey in Spain. Alcohol patterns were defined based on (1) average intake: individuals were classified as low risk (1–20 g/day in men and 1–10 g/day in women) and high risk (> 20 g/day in men or > 10 g/day in women), (2) binge drinking, and (3) alcoholic beverage preference. Non-adherence to the Mediterranean diet was defined as scoring < 7 points on an adapted Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener index (range 0–10). Odds ratios (OR) were estimated using logistic regression models adjusted for relevant covariates.

Results

Compared to non-drinkers, low and high-risk drinkers were more likely to report non-adherence to the Mediterranean diet: ORs 1.35 (95% CI 1.23; 1.49) and 1.54 (95% CI 1.34; 1.76), respectively. Similarly, reports of binge drinking less than once a month was associated with higher likelihood of non-adherence (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.04; 1.31). Individuals reporting no preference for a specific beverage and those with a preference for beer or for spirits had lower adherence: ORs 1.18 (95% CI 1.05; 1.33), 1.31 (95% CI 1.17; 1.46), and 1.72 (95% CI 1.17; 2.54), respectively, while a preference for wine showed no association (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.90; 1.13).

Conclusion

Alcohol consumption, even in low amounts, is associated with lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Therefore, alcoholic beverages should not be included in measures that define the Mediterranean diet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Alcohol consumption is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide, with risk increasing with rising levels of consumption [1]. In 2016, excessive alcohol consumption was responsible for 3 million deaths, 5.3% of all deaths, and 5.1% of all Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) [2]. Further, about 750,000 new cancer cases, 4.1% of the total, were ascribed worldwide to this risk factor in 2020 alone [3].

Alcohol is an intricate component of any diet with numerous effects on appetite [4]. A recent meta-analysis concludes that not only alcohol consumption increases energy intake but that even low amounts of alcohol increase food consumption [5]. Overall consensus is that excessive alcohol drinkers generally have lower diet quality [6,7,8,9,10], with the discussion increasingly focusing on evidence linking light alcohol consumption and poorer diet [6, 10]. However, others fail to detect dietary differences between light-drinkers and non-drinkers [8, 9]. The scientific community´s ongoing debate on the potential benefits of low-to-moderate alcohol consumption on all-cause and cardiovascular disease-mortality [11, 12] only underscores the importance of ascertaining the alcohol-diet association; as any such health benefits may actually be accounted for by drinkers´ dietary habits differing from those of non-drinkers [9, 13].

Many studies on the alcohol-diet relationship analyze how the quantity of alcohol ingested affect diet characteristics. However, consumption patterns may be also associated with variations in diet quality and, thus, examining patterns would contribute to a better understanding of this association [7]. Finally, it is essential to consider the role of binge drinking, as well as the type of alcoholic beverage consumed, since large variations in the results have been described depending on the geographical area [14].

The Mediterranean diet (MD) stands for a dietary pattern characteristic of the European southern regions in the early 1960s and considered a model for a healthy diet [15,16,17]. Moderate alcohol consumption, especially wine, has traditionally been counted as one of its features [17]. In fact, pictograms describing the MD usually include representations of alcoholic beverages [18]. However, previous studies conducted in Spain [19] cast doubt on this relationship, concluding that alcohol is currently not one of the MD´s distinctive elements.

This study´s main aim was to evaluate the association between various alcohol consumption patterns and the adherence level to the MD among a representative sample of the Spanish adult population.

Methods

Study design and population

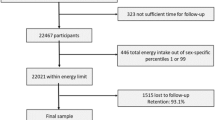

We analyzed data from two surveys, the 2017 Spanish National Health Survey and the 2020 European Health Survey in Spain. These surveys are representative of the Spanish population and use harmonized sample design and questionnaires collecting data on sociodemographic characteristics, health status, social and environmental determinants, lifestyles, and access to and use of health services. Their multistage sampling selects all provinces first, followed by a sample of municipalities within each province, stratified by population size. Subsequently, a sample of census tracts is selected within these municipalities. Finally, a sample of households is picked within each tract, and an adult aged ≥ 15 years is chosen. Participants are interviewed face-to-face with the aid of an electronic device (Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing-CAPI) [20, 21].

The overall response rate (number of completed interviews relative to the total number of eligible households) was 70.3%, resulting in an initial sample size of 45,161 subjects. After excluding participants with missing data in any of the study variables, the final sample consisted of 44,834 individuals. In the case of 1417 participants, the survey was answered by a proxy (a person responding on behalf of the selected respondent).

Study variables

Alcohol consumption patterns

Alcohol consumption (frequency and amount) of six types of alcoholic beverages (wine, beer, vermouth and aperitifs, spirits, mixed drinks, and cider) was recorded and analyzed. Participants were classified into the following categories: non-drinkers (individuals who never drank alcohol or only took a few sips throughout their life), former drinkers (individuals who reported quitting alcohol and reported zero consumption in the past 12 months), occasional drinkers (≤ 1 time per week), low-risk alcohol consumers (up to 20 g/day for men and 10 g/day for women) and high-risk alcohol consumers (> 20 g/day for men and > 10 g/day for women) [22]. Binge drinking was defined as the consumption of ≥ 6 or ≥ 5 standard drinks within a 4–6 h period for men and women, respectively [23], and its frequency classified as never, < 1 time per month, monthly, weekly/daily. Alcoholic beverage preference for wine, beer, or spirits was considered defined if the consumption of any of these beverages accounted for ≥ 80% of the total alcohol intake [19, 24]. Additionally, we estimated total consumption of each beverage in grams per day (0, > 0–10, > 10–20, > 20).

Mediterranean diet

We used an adapted version of the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) [25] to measure participants’ degree of adherence to the MD. We assigned a score ranging from 0 to 10 based on the reported consumption of the following items: 1–2 servings of fruit per day (1 point), > 3 servings per day (2 points); 1 serving of vegetables per day (1 point), > 1 serving per day (2 points); ≥ 3 servings of legumes per week (1 point); ≥ 3 servings of fish per week (1 point); < 1 serving of meat per day (1 point); < 1 serving of sugary drinks per day (1 point); < 3 servings of sweets per week (1 point); < 3 servings of fast food (including snacks) per week (1 point). A score < 7 points was considered non-adherence to the MD.

Covariates

The following variables were included in multivariate analyses as covariates: Age group (15–24 years of age, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥ 75); sex; educational level [primary education (6–12 years of schooling) or lower, first stage of secondary education (12–16 years of schooling), second stage of secondary education (16–18 years of schooling), university education (≥ 18 years of schooling)]; country of birth (Spain, other); size of residential municipality (> 500,000 inhabitants, province capital, > 100,000–500,000, > 50,000–100,000, > 20,000–50,000, 10,000–20,000, and < 10,000); body mass index (BMI) [ratio of weight (kg) to square of height (m)]; tobacco consumption (non-smoker, former smoker, smoker of up to 14 cigarettes/day, smoker > 14 cigarettes/day); sedentary leisure time (some degree of physical activity or none); perceived health status (very good, good, fair, poor, very poor); and survey year (2017, 2020).

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses to ascertain the sample´s prevalence and distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, perceived health status, and MD adherence by alcohol consumption pattern. Associations with non-adherence to the MD were analyzed with fully-adjusted multivariate logistic regression models, estimating odds ratios (OR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). Binge drinking was also adjusted for when analyzing average alcohol consumption and, vice versa, we controlled for quantity of alcohol consumed when evaluating binge drinking. Further, in the models where the primary independent variable was alcoholic beverage preference, we took into account both total daily alcohol intake (g/day) and binge drinking. Finally, when wine, beer, and liquor consumption (0 g/day, > 0–10, > 10–20, and > 20) were the primary independent variable, the models were adjusted for binge drinking.

Furthermore, we assessed whether these associations varied by age group (< 65 vs ≥ 65), sex, or educational level (4 categories) including the corresponding interaction terms in the models. When any interaction terms were statistically significant (p < 0.05), the results were stratified according to the corresponding sociodemographic variables.

Sensitivity analyses included examining these associations using the MEDAS adapted index in a continuous form. First, the Spearman’s correlation between the continuous form of the MEDAS index and the alcohol total consumption (g/day) was calculated. Second, coefficients β were estimated through linear regression models adjusted for the same covariates. Third, logistic regression models of the associations of interest were also repeated excluding proxies´ data. Finally, logistic regression models examining binge drinking and total consumption of each type of beverage regarding MD non-adherence were repeated excluding former drinkers.

The estimates were weighted using sampling weights to ensure proportional representation. All analyses were conducted using the survey procedure in Stata v.17 (StataCorp, College Station, USA) to incorporate the complex sample design features of the surveys.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the sample according to alcohol consumption patterns. Among the participants, 21.5% were classified as non-drinkers, 13% as former drinkers, 29.7% as occasional drinkers, 28.1% as low-risk drinkers, and 7.7% as high-risk drinkers. Binge drinking in the previous 30 days was reported by 7% of the participants. Among drinkers, 21.2%, 35.7%, and 2.8% reported preference for wine, beer, and spirits, respectively. A vast majority of the study sample, 76.3%, reported no adherence to the MD.

Average alcohol consumption, binge drinking, and Mediterranean diet

Compared to non-drinkers, former and occasional drinkers were more likely to report poorer adherence to the MD (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.06; 1.30 and OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.03; 1.24, respectively). Adherence to MD was even poorer among low-risk and high-risk drinkers, with ORs of 1.35 (95% CI 1.23; 1.49) and 1.54 (95% CI 1.34; 1.76), respectively (Table 3). No significant differences were observed between individuals who did and did not engage in binge drinking in the previous 30 days (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.78; 1.03). However, individuals who binge drank less than once a month had lower adherence to the MD (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.04; 1.31) compared to those who reported no binge drinking at all.

Type of alcoholic beverage and Mediterranean diet

Compared to non-drinkers, former and occasional drinkers and also individuals who reported no preference for a certain alcoholic beverage showed lower adherence to the MD (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.07; 1.31; OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.04; 1.25, and OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.13; 1.48, respectively) (Table 4). Individuals with a preference for beer reported poorer adherence to the MD (OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.26; 1.63), and the lowest adherence was observed among those with a preference for spirits (OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.26; 2.79). A preference for wine failed to show an association with MD adherence (OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.96; 1.24). The direction of the associations was the same when considering the total consumption of wine, beer, and spirits in a categorized manner (Table 4).

Subgroup analysis

Sex. Statistically significant interactions were observed between sex and low-risk and high-risk consumption, as well as binge drinking less than once a month (p for interaction < 0.05) (Table 5). Men had an OR of 1.50 (95% CI 1.27; 1.77) for low-risk consumption and 1.84 (95% CI 1.49; 2.28) for high-risk consumption, whereas these values were lower in women (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.16; 1.48; and OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.19; 1.70, respectively). Regarding binge drinking less frequently than once a month, the OR for men was 1.25 (95% CI 1.07; 1.45), and no association was found in women.

Age. Statistically significant interactions were observed between age and occasional, low-risk and high-risk consumption, binge drinking and preferred beverage consumption (p for interaction < 0.05). The results of the age-stratified analyses (< 65 vs. ≥ 65) are described in Table 6. Regarding average consumption, the association in both groups were in the same direction but the magnitude was greater in individuals younger than 65 years of age. Regarding binge drinking, the better adherence to the MD among ≥ 65 year-old weekly binge drinkers is noteworthy (OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.39; 0.84). Lastly, individuals under 65 reporting no beverage preference or with a preference for beer and spirits showed poorer adherence to the MD. No association was found among individuals 65 and over.

Educational level. No statistically significant interactions were detected between educational achievement and alcohol consumption indicators (data not shown).

Sensitivity analysis

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the continuous form of the MEDAS index and the alcohol total consumption (g/day) was − 0.06. When compared to non-drinkers, linear regression results show that any drinker, regardless of the amount of average alcohol reported, scored a significantly lower adherence to the MD (measured with the MEDAS index in its continuous form). This was even more notable in low-risk and high-risk drinkers (Supplementary Table 1). Further regression analyses on the type of beverage produced similar results to those observed using the categories of the MEDAS index (Supplementary Table 2).

Overall analyses excluding proxies, as well as analyses of binge drinking and beverage preference excluding former drinkers, produced similar results to those observed for the entire sample (Supplementary Table 3, 4, and 5).

Discussion

The main results of the study show that, compared to the abstemious population, both low-risk and high-risk alcohol consumption are associated with poorer adherence to the MD. This association is also observed among former and occasional drinkers, occasional binge drinkers, those with no beverage preference as well as among those with a preference for beer or for spirits.

Our findings support past work concluding that both low-risk and high-risk alcohol consumers had diets of poorer quality compared to abstainers or non-drinkers [7, 10]. Overall, poorer diet quality has been reported as average alcohol consumption increases [7], as our results confirm regarding adherence to the MD. However, other authors [8, 9, 24] failed to detect any significant differences between the dietary patterns of moderate drinkers and non-drinkers.

It is worth highlighting the following work conducted with similar methods as ours. León-Muñoz and colleagues, using population-based data aged 18–64 years from Spain, also failed to find differences in adherence to the MD between moderate drinkers and non-drinkers. However, adherence was significantly lower in high-risk drinkers [19]. These findings, in turn, supported Valencia-Martín et al.’s previous study in Madrid region [24] regarding poor diet and excessive drinking.

Regarding gender differences, men´s greater magnitude of non-adherence to the MD in all categories of average consumption may be related to their higher frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption compared to women’s [26].

In Anglo-Saxon countries, binge drinking tends to be a sporadic practice and, on such occasions, the consumption takes place over a short period of time. In Mediterranean regions, however, the binging tends to occur more often but spread over several hours with a strong social component [23]. Whereas the Anglo-Saxon habit is clearly associated with poorer diet quality [8], findings in Spain are inconclusive. Authors have reported both higher adherence to the MD [19] and poorer adherence to healthy eating guidelines [24] among binge drinkers. Our results contribute to the current controversy because, contrary to expectations, we failed to detect any significant differences in adherence to the MD between binge drinkers and never binge drinkers. Further, only those who binge drank less than once a month reported poorer adherence to the MD than those never engaging in it.

Due to the scarce evidence available, any gender and age differences found in this association were interpreted cautiously. Several studies report higher prevalence of binge drinking in men [26,27,28,29], which could be attributed to a combination of biological and cultural factors [26, 27] which, in turn, may also influence the gender-based relationship between binge drinking and diet quality. Meanwhile, compared to their older counterparts (≥ 65), younger individuals are increasingly departing from the MD [30] and they often engage in sporadic binge drinking during nighttime social events or open-air drinking parties known in Spain as “botellón” [31,32,33]. Binge drinking in older individuals is more often associated to higher frequency and around meals. However, further research should delve into these findings as they may have significant implications for public health.

Regarding beverage preference, our findings support previous descriptions of poorer dietary habits among individuals with a preference for beer or spirits [14, 34]. However, we failed to find any association with a preference for wine consumption as did León-Muñoz and colleagues, who reported a higher adherence to the MD among individuals with a preference for wine compared to those with no beverage preference [19]. We get similar results when excluding non-drinkers from the analysis and using those with no preference as reference category. Another study conducted in Spain reported no association between beverage preference and adherence to the MD [35]. Only in Northern European countries and the United States has a preference for wine consumption been associated with higher-quality dietary patterns [36,37,38]. This could be attributed to the fact that in Mediterranean countries, wine is consumed across all socioeconomic strata due to its affordable price and strong connection to food consumption.

Among the limitations of this study to consider when interpreting its findings is its cross-sectional nature, which prevents establishing causal associations between alcohol consumption and adherence to the MD. Additionally, the use of self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias and underestimation of alcohol consumption, especially for high-risk or occasional consumption [39, 40].

Among the many strengths of the study, we would highlight the comprehensive assessment of alcohol consumption patterns in a large, population-based sample of the Spanish adult population. Particularly relevant was the distinction made among abstainers, former drinkers, and occasional drinkers. These consumer groups often fail to account for high percentages of study samples and are usually combined into a single category as “non-drinkers,” making any interpretation problematic.

Regarding data analysis, a key strength was the full adjustment for relevant covariates in the statistical analyses. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses using the continuous form of MEDAS index confirmed that our results were not due to the cutoff point chosen to define adherence to the MD. Instead, they showed consistent trends supporting the logistic regression results. Lastly, the analyses excluding former drinkers and proxies provided further evidence that the results were robust and consistent across the entire sample.

Conclusions

Our results challenge the traditional belief that consuming small amounts of alcohol or certain alcoholic beverages, especially wine, are part of the Mediterranean diet pattern. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and provide more robust evidence on the association between alcohol consumption and dietary patterns. If these findings were confirmed by future studies, it would be advisable to exclude the inclusion of alcohol consumption in dietary quality questionnaires, especially those focused on evaluating adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Furthermore, it may be necessary to emphasize the potential negative effects of alcohol consumption on overall diet quality and health outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- MD:

-

Mediterranean diet

- MEDAS:

-

Mediterranean diet adherence screener

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

References

Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C et al (2018) Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 392:1015–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639

Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H et al (2021) Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 22:1071–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5

Yeomans MR, Caton S, Hetherington MM (2003) Alcohol and food intake. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 6:639–644. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200311000-00006

Kwok A, Dordevic AL, Paton G et al (2019) Effect of alcohol consumption on food energy intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 121:481–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518003677

Breslow RA, Guenther PM, Juan W, Graubard BI (2010) Alcoholic beverage consumption, nutrient intakes, and diet quality in the US adult population, 1999–2006. J Am Diet Assoc 110:551–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.026

Breslow RA, Guenther PM, Smothers BA (2006) Alcohol drinking patterns and diet quality: the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 163:359–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwj050

Parekh N, Lin Y, Chan M et al (2021) Longitudinal dimensions of alcohol consumption and dietary intake in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort (1971–2008). Br J Nutr 125:685–694. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520002676

Fawehinmi TO, Ilomäki J, Voutilainen S, Kauhanen J (2012) Alcohol consumption and dietary patterns: the FinDrink study. PLoS One 7:e38607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038607

Brenes JC, Gómez G, Quesada D et al (2021) Alcohol contribution to total energy intake and its association with nutritional status and diet quality in eight Latina American countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:13130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413130

Krittanawong C, Isath A, Rosenson RS et al (2022) Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular health. Am J Med S0002–9343(22):00356–00364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.021

Stockwell T, Zhao J, Panwar S, et al (2016) Do “moderate” drinkers have reduced mortality risk? A systematic review and meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 77:185–198. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2016.77.185

Kesse E, Clavel-Chapelon F, Slimani N, Van Liere M (2001) Do eating habits differ according to alcohol consumption? Results of a study of the French cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (E3N-EPIC). Am J Clin Nutr 74:322–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/74.3.322

Sluik D, Bezemer R, Sierksma A, Feskens E (2016) Alcoholic beverage preference and dietary habits: a systematic literature review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 56:2370–2382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2013.841118

English LK, Ard JD, Bailey RL et al (2021) Evaluation of dietary patterns and all-cause mortality: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2122277. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22277

Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R et al (2008) Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 337:a1344. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1344

Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A et al (1995) Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr 61:1402S-1406S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1402S

Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D et al (2011) Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr 14:2274–2284. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002515

León-Muñoz LM, Galán I, Valencia-Martín JL et al (2014) Is a specific drinking pattern a consistent feature of the Mediterranean diet in Spain in the XXI century? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24:1074–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.04.003

Ministerio de Sanidad e Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2017) Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2017. (Metodología). https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuestaNac2017/ENSE17_Metodologia.pdf

Ministerio de Sanidad e Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2020) Encuesta Europea de Salud en España 2020. (Metodología). https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/EncuestaEuropea/EncuestaEuropea2020/Metodologia_EESE_2020.pdf

Sordo L, Córdoba R, Gual A, Sureda X (2020) Low-risk alcohol drinking limits based on associated mortality. Rev Esp Salud Publica 94:e202011167

Valencia Martín JL, Galán I, Segura García L, et al (2020) [Binge drinking: the challenges of definition and its impact on health.]. Rev Esp Salud Publica 94:e202011170

Valencia-Martín JL, Galán I, Rodríguez-Artalejo F (2011) The association between alcohol consumption patterns and adherence to food consumption guidelines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35:2075–2081. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01559.x

Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R et al (2011) A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr 141:1140–1145. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.135566

Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF et al (2009) Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction 104:1487–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x

Hernández-Vásquez A, Chacón-Torrico H, Vargas-Fernández R et al (2022) Gender differences in the factors associated with alcohol binge drinking: a population-based analysis in a Latin American country. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:4931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094931

Mäkelä P, Gmel G, Grittner U et al (2006) Drinking patterns and their gender differences in Europe. Alcohol Alcohol 41:i8–i18. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agl071

Valencia-Martín JL, Galán I, Rodríguez-Artalejo F (2007) Binge drinking in Madrid, Spain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31:1723–1730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00473.x

León-Muñoz LM, Guallar-Castillón P, Graciani A et al (2012) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern has declined in Spanish adults. J Nutr 142:1843–1850. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.164616

Calafat A, Juan M, Becona E, et al (2005) Alcohol consumption in the logic of the “botellón” (binge drinking in the streets in Spain). Adicciones 17:193–202. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.368

Calafat A, Blay NT, Hughes K et al (2011) Nightlife young risk behaviours in Mediterranean versus other European cities: are stereotypes true? Eur J Pub Health 21:311–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq141

Farke W, Anderson P (2007) Binge drinking in Europe. Adicciones 19:333–339. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.293

Sluik D, van Lee L, Geelen A, Feskens EJ (2014) Alcoholic beverage preference and diet in a representative Dutch population: the Dutch national food consumption survey 2007–2010. Eur J Clin Nutr 68:287–294. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.279

Alcácera MA, Marques-Lopes I, Fajó-Pascual M et al (2008) Alcoholic beverage preference and dietary pattern in Spanish university graduates: the SUN cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr 62:1178–1186. https://doi.org/10.1038/SJ.EJCN.1602833

Barefoot JC, Grønbæk M, Feaganes JR et al (2002) Alcoholic beverage preference, diet, and health habits in the UNC Alumni Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 76:466–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/76.2.466

Herbeth B, Samara A, Stathopoulou M et al (2012) Alcohol consumption, beverage preference, and diet in middle-aged men from the STANISLAS Study. J Nutr Metab 2012:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/987243

Tjønneland A, Grønbæk M, Stripp C, Overvad K (1999) Wine intake and diet in a random sample of 48763 Danish men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 69:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/69.1.49

Boniface S, Kneale J, Shelton N (2014) Drinking pattern is more strongly associated with under-reporting of alcohol consumption than socio-demographic factors: evidence from a mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 14:1297. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1297

Boniface S, Scholes S, Shelton N, Connor J (2017) Assessment of non-response bias in estimates of alcohol consumption: applying the continuum of resistance model in a general population survey in England. PLoS One 12:e0170892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170892

Funding

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Health. Government Delegation for the National Drugs Plan (PI 2021I033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JF: Conceptualization, methodology, writing the first draft and editing. CO and TL: Methodology, data curation, data analysis, writing review and editing. MT and EG: Interpretation of the findings, critically revised the manuscript and editing. IG: Conceptualization, study design, methodology, writing the first draft and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article presents independent research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Institute of Health Carlos III.

Consent to participate

The participant's signed consent was obtained before the interview.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fontán-Vela, J., Ortiz, C., López-Cuadrado, T. et al. Alcohol consumption patterns and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the adult population of Spain. Eur J Nutr 63, 881–891 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03318-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03318-2