Abstract

The prediction skills of climate model simulations in the western tropical Pacific (WTP) and East Asian region are assessed using the retrospective forecasts of seven state-of-the-art coupled models and their multi-model ensemble (MME) for boreal summers (June–August) during the period 1983–2005, along with corresponding observed and reanalyzed data. The prediction of summer rainfall anomalies in East Asia is difficult, while the WTP has a strong correlation between model prediction and observation. We focus on developing a new approach to further enhance the seasonal prediction skill for summer rainfall in East Asia and investigate the influence of convective activity in the WTP on East Asian summer rainfall. By analyzing the characteristics of the WTP convection, two distinct patterns associated with El Niño-Southern Oscillation developing and decaying modes are identified. Based on the multiple linear regression method, the East Asia Rainfall Index (EARI) is developed by using the interannual variability of the normalized Maritime continent-WTP Indices (MPIs), as potentially useful predictors for rainfall prediction over East Asia, obtained from the above two main patterns. For East Asian summer rainfall, the EARI has superior performance to the East Asia summer monsoon index or each MPI. Therefore, the regressed rainfall from EARI also shows a strong relationship with the observed East Asian summer rainfall pattern. In addition, we evaluate the prediction skill of the East Asia reconstructed rainfall obtained by hybrid dynamical–statistical approach using the cross-validated EARI from the individual models and their MME. The results show that the rainfalls reconstructed from simulations capture the general features of observed precipitation in East Asia quite well. This study convincingly demonstrates that rainfall prediction skill is considerably improved by using a hybrid dynamical–statistical approach compared to the dynamical forecast alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As one of the major monsoon climate regions in the world, East Asia suffers frequently from severe floods and/or droughts in summer. Many researchers have studied the characteristics of the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM), including the large-scale circulation related to the rainband (Huang and Sun 1992; Huang 2004; Gong et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013a). The atmospheric circulation of EASM is characterized by a low-level convergence zone between southerlies from the tropics and weak northerlies from mid-latitudes, and upper-tropospheric westerlies in the north of the subtropical ridge (Wang and Xu 1997).

The seasonal climate prediction of East Asian summer rainfall remains a challenging issue with various limitations, in spite of the facts that refined statistical methods have reasonably improved the predictability of the simulated outcomes (Zhu et al. 2008; Wang and Fan 2009; Lang and Wang 2010; Ke et al. 2011) and state-of-the art climate prediction models have been improved significantly (Wang et al. 2007, 2008a, 2009). Several studies have also revealed that the models have not only difficulties in simulating the mean climate state over the EASM region, but also deficiencies in predicting the variability of mean summer rainfall anomalies (Kang et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2004, 2008a, 2009; Yang et al. 2008; Liang et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2010).

Unlike the East Asian region, the forecast skill for the summer rainfall anomaly in the western tropical Pacific (WTP) shows relatively high performance (Lee et al. 2011b; Li et al. 2012). The present study results also support the superior predictability of individual models, including multi-model ensemble (MME), for precipitation and temperature in WTP, in comparison to the East Asian region (Figs. 1, 2, 3). Because the low-level tropospheric circulation anomalies over the WTP, which affect atmospheric moisture transport into the East Asian monsoon zone, play an important role in reinforcing precipitation in the East Asian region (Nitta 1987; Huang and Sun 1992; Lau et al. 2000; Lu 2001), the seasonal predictability of the WTP summer anomalies is of central importance to seasonal prediction of East Asian summer rainfall. Sun and Chen (2012) also mentioned that the climate information from the tropical region is very significant to improve the prediction of the extratropical rainfall during the boreal summer.

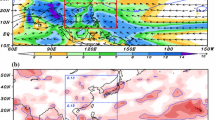

Temporal correlation coefficients (TCCs) between the observed and predicted precipitation over the East Asian (90°E–160°E, 20°–60°N) region from individual models and MME. The contour line depicts the region of significant correlation (0.352) at the 90 % confidence level from a two-tailed Student’s t test

Same as Fig. 1, except for the Maritime continent-western tropical Pacific (MC-WTP: 100°E–180°E, 20S°–20°N) region

Scatter diagram between the spatial PCCs and NRMSEs for precipitation (left) and temperature (right) at 850 hPa over the two regions of the East Asia (red) and MC-WTP (blue) derived from the individual model and MME predictions. The x (mean of individual models) indicates the average of the PCC (or NRMSE) skills of all constituent models

The present study investigates the limitations and possibilities for seasonal climate prediction, with a particular focus on summer rainfall anomalies in the WTP and East Asian region, using available hindcast datasets for the 23-year period of 1983–2005 obtained from the operational climate forecast models in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Climate Center (APCC). We focus on developing a new approach to further improve the prediction skill of EASM rainfall using the characteristics of convective activity in the WTP affecting the East Asian monsoon rainfall. Further issues that are addressed in this study include: (1) an assessment of the predictive quality of the climate model simulations for the East Asian summer rainfall and WTP convection, (2) investigation of the possible methods to improve the predictability of the East Asian monsoon rainfall using predictable information and (3) an evaluation of the prediction skill for the reconstructed summer rainfall over the East Asian region by applying the developed approach method.

Section 2 presents a brief description of the observational data, coupled model data, and statistical methods used in this study. Section 3 describes the relationship between the WTP convective activity and East Asian summer rainfall, and compares the observed and simulated convective activity over the WTP. Section 4 describes the development of a hybrid dynamical–statistical method for improving the prediction skill of the East Asian summer rainfall and the assessment of the skills for the reconstructed rainfall in East Asia. The final section presents the summary and conclusions.

2 Data and statistical methods

2.1 Data

The boreal summer (June through August, JJA) retrospective seasonal forecast outputs at a lead time of 1-month for the period of 1983–2005 from seven coupled atmosphere–ocean climate models, which contribute to the operational 6-month 1-tier MME seasonal prediction system of the APCC, have been used in the present study. These models are selected due to the availability of the longest and most continuous quality-controlled common hindcast datasets. A brief description of the models is presented in Table 1. In addition, the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP)—Department of Energy (DOE) reanalysis 2 data (Kanamitsu et al. 2002), and the Climate Prediction Center Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP) data (Xie and Arkin 1997) are used for the same season and period as the model retrospective forecasts for atmospheric variables and rainfall. Before the analysis is computed, observed data and seasonal hindcasts from all models are interpolated to a common 2.5° resolution grid.

2.2 Statistical methods

We adopt a simple composite MME method (Peng et al. 2002; Kang et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2008, 2009, 2011a, 2013a, b), which assigns equal weights to the ensemble mean predictions of individual models. The performance of this method is on par with the best available operational MME techniques (Lee et al. 2009). Henceforth, MME refers to this simple composite method, unless otherwise specified.

The MME results are generated by the application of a bias correction (Lee et al. 2009, 2011a) to model forecast anomalies, which are obtained from the standard ‘‘leave-one-out’’ cross-validation method (Michaelsen 1987; Jolliffe and Stephenson 2003; World Meteorological Organization 2006; Lee et al. 2013a, b). This cross-validation method essentially computes seasonal anomalies for each model parameter, from the corresponding yearly climatological means obtained by excluding information from the target year, as well as those of observations.

We use the Student’s two-tailed t test (Wilks 1995; Spiegel and Stephens 2008) to compute the statistical significance of temporal correlations. We compute the statistical significance using the simple number of degrees of freedom estimated as N-2, where N is 23, the number of summer seasons during the study period.

3 Relationship between the observed WTP convection and East Asian summer rainfall

3.1 Characteristics of convective activity over the WTP

Many studies (Nitta 1987; Huang and Sun 1992; Lau et al. 2000; Lu 2001; Sun et al. 2009) have addressed the effect of the low-level circulation in the tropical western Pacific on the variability of rainfall over the East Asian region. These findings clearly show that the convective activity induced by heating in the WTP is closely related to East Asian summer rainfall. We expect an investigation aimed at improving our understanding of the empirical relationship between the two regions to improve the prediction skills of the East Asian summer rainfall. First, the performance of the climate prediction models and their MME used in this study is assessed in terms of the simulated rainfall anomalies.

Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of the prediction skills of all individual models and their MME for precipitation over the East Asian (90°E–160°E, 20°–60°N) region in terms of temporal correlation coefficient (TCC) at each grid point for the period of 1983–2005. The statistical significance of the TCCs is computed using Student’s two‐tailed t test. The region of significant correlation at the 90 % confidence level is outlined. In general, the predicted skills over the ocean areas are significantly superior to those over the land areas in most of the models. We also find that the MME prediction skills are considerably improved as compared to those of the individual models. However, certain limitations remain in improving the predicted rainfall in the mid-latitude region, particularly over East Asia. In contrast to these concerns, TCCs over the Maritime continent-WTP (MC-WTP: 100°E–180°E, 20S°–20°N) display considerably more significant values and higher correlations (Fig. 2). The prediction skills of most individual models except for MSC_CANCM3 and MSC_CANCM4 show high performance. Especially, the area average of the MME prediction skill reaches more than 0.4 for the period of 1983–2005, which is statistically significant at the 95 % confidence level based on Student’s two-tailed t test. Figure 3 shows the scatter diagram between the spatial pattern correlation coefficients (PCCs; Jolliffe and Stephenson 2003; World Meteorological Organization 2006) and normalized root mean square errors (NRMSEs; Jolliffe and Stephenson 2003; World Meteorological Organization 2006) with respect to the corresponding observed standard deviation for precipitation and temperature at 850 hPa from all seven models and MME predictions over the abovementioned two regions. We calculated the PCC and NRMSE between observed and predicted anomalies for each grid point over the regions in every year, and then time-averaged skill and error scores were computed for each model and MME. The prediction skills of MMEs as well as individual models for both variables differ markedly between the East Asia and MC-WTP regions, although the differences between the NRMSEs for MME predictions are relatively smaller than those of the PCCs. Furthermore, the PCC difference of the MME prediction between the two regions for precipitation is considerably higher than that for temperature.

Based on the aforementioned close relationship between observed and predicted precipitation over the MC-WTP region, we carry out empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis to identify the dominant spatial patterns and interannual variability of rainfall anomalies represented as the convective activity in the tropical western Pacific. Figure 4 displays the spatial distributions and time series of the principal components (PCs) of the first and second EOF modes for observed rainfall anomaly. The fraction of variance of the first two EOF modes is more than 50 %. In the first EOF mode, the structures of the zonal dipole mode, which are located in the south of the Philippines around 130°E (positive node) and western Pacific around 160°E (negative node) near the equator, are formed. The second EOF mode of the variability of the rainfall anomaly in MC-WTP features a tripole pattern. The enhanced (reduced) rainfall is located near the Philippine Sea (around 15°N, 140°E), and the patterns of the suppressed (increased) rainfall are exhibited in the Island of Borneo around 115°E within the equatorial region and western Pacific around 170°E and south of the equator. Cross-validation is applied to assess the variability of the leading EOF mode for the 23-year period of 1983–2005 (figures not shown). The cross-validated patterns, corresponding to the two leading EOF modes, between each target year are similar, as shown in Fig. 4, except for a few out-of-phase years.

To investigate the influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on convective activity in the tropical western Pacific and the relationship between the two, we carry out composite analysis for summer rainfall anomalies by selecting the ENSO developing and ENSO decaying summers among all 23 summers from 1983 to 2005. In this study, we follow the method of Wu et al. (2009), who classify ENSO into the developing and decaying summers based on the Niño 3.4 index. Seven summers (El Niño: 1987, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2002, 2004, La Niña: 1999) and thirteen summers (El Niño: 1983, 1988, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2003, 2005, La Niña: 1984, 1985, 1989, 1996, 2000, 2001) are classified as the ENSO developing and decaying types, respectively. Figure 5a, b indicate composite patterns for summer rainfall anomalies of each ENSO type over the tropical western Pacific. We can find that these patterns are consistent with the Fig. 3c and d of Wu et al. (2009), respectively. The figures also show that the composite rainfall anomaly maps are very similar to the EOF modes of Fig. 4. Especially, it is notable that the PCC between the composite pattern of the ENSO developing (decaying) type and the first (second) EOF mode shows a significantly high skill score of −0.861 (−0.816), which is beyond the 99 % confidence level. These results confirm that the major patterns of summer rainfall represented as the western Pacific convection are strongly associated with the development and decay of ENSO.

Figure 6 displays the correlation and regression patterns between the observed rainfall and the normalized PC time series of the two leading EOF modes in Fig. 4c. The correlation and regression patterns obtained from each PC are similar to one another with little difference from the spatial patterns of the EOF modes in Fig. 4a, b. To quantitatively depict the spatial patterns of precipitation over the WTP, normalized MC-WTP Indices (MPIs) by the corresponding standard deviation for MPIs are defined as the difference of the area-averaged precipitation in the dipole (Fig. 6a) and tripole (Fig. 6b) mode pattern. The MPIs can be calculated according to the following formula:

Temporal correlation (shaded) and regression (contour) patterns between observed precipitation and normalized PC time series of the a first and b second EOF modes from the observed precipitation. c The corresponding normalized PC time series of the first (red line) and second (blue line) EOF modes, and normalized MPIs obtained by the area-averaged precipitation differences. The dashed lines (gray) in Fig. 6a, b represent the region of significant values at the 90 % confidence level from a two-tailed Student’s t test

MPI1 (MPI2) obtained from the dipole (tripole) pattern exhibits a nearly consistent variation with the PC1 (PC2) time series. The correlation coefficients between the MPIs and PCs reach 0.97 and 0.94, respectively. In addition, the correlation coefficient between the two MPIs is nearly similar to that between the two PC time series representing the orthogonal feature to each other.

3.2 Influences of convective activity over the WTP on the EASM region

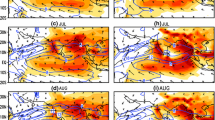

To better understand the impacts of the WTP convection on the summer rainfall and atmospheric circulation over the EASM region, Fig. 7 presents the summer rainfall and wind circulation at 850 hPa associated with the normalized MPIs. The meridional tripole structure of the rainfall is evident in Fig. 7a, b. In Fig. 7b, particularly, the rainfall distribution associated with MPI2 shows a meridional tripole pattern, termed the Pacific-Japan (PJ) pattern by Nitta (1987), with the suppressed rainband along the eastern part of China, Korean peninsula and eastern Japan, and the enhanced rainfall pattern in the vicinity of the western Pacific (including the South China Sea and Philippine Sea) and the Okhotsk Sea. The rainfall pattern of Fig. 7a related to MPI1 at the north of about 15°N is similar to a slight northward shifted pattern of the meridional tripole structure in Fig. 7b associated with the PJ teleconnection pattern. The wind field at 850 hPa displays a similar feature to the regressed pattern of rainfall over East Asia. The anticyclonic circulation pattern covers the Korean peninsula and Japan, and the cyclonic circulation field is located at the southern and northern regions (Fig. 7c, d).

Regression patterns of the precipitation (unit: mm day−1, top panels) and wind circulation at 850 hPa (unit: m s−1, bottom panels) on the normalized MPI1 (left) and MPI2 (right), respectively. The gray dashed lines (top) and wind vectors (bottom) depict the region of significant values at the 90 % confidence level from a two-tailed Student’s t test

Figure 8 illustrates how the patterns of sea level pressure and 500 hPa geopotential height fields over the East Asian region are affected by the MPIs over the WTP. For the geopotential height at 500 hPa, a wave train, with opposite signs of summer rainfall patterns, initiating around the Philippines, propagates along the coast of East Asia through the western part of North America (Fig. 8a, b). A similar structure also appears in the regressed pattern of the sea level pressure associated with MPIs (Fig. 8c, d). However, it is slightly weaker than the upper level pattern. In addition, the wave train patterns of the summer rainfall and upper level pressure associated with the tropical convective activity over the WTP in this study are very similar to the East Asia/Pacific (EAP) teleconnection pattern suggested by Huang and Sun (1992) and the EASM structure related to EAP Index defined by Huang (2004).

Same as Fig. 7, but for the geopotential height at 500 hPa (unit: m, top panels) and sea level pressure (unit: hPa, bottom panels). The gray dashed lines represent the region of significant values at the 90 % confidence level from a two-tailed Student’s t test

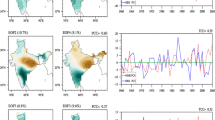

These study results objectively support the possible use of the MPIs in influencing to the EASM region. Figures 9 and 10 reveal how well the East Asia summer rainfall affected by the MPIs represented as the western tropical convection describes the major features of the East Asian rainfall pattern and its interannual variability. The regression results of the summer rainfall on the EASM Index (Wang and Fan 1999; Wang et al. 2008b; Lee et al. 2013a; henceforth, EASMI), which is defined as the difference of the area-averaged zonal wind at 850 hPa between the southern (5°–15°N, 90°–130°E) and northern (22.5°–32.5°N, 110°–140°E) portion of the monsoon domain, and MPIs are compared with the spatial pattern of the first EOF mode (fraction of variance is 26.56 %) of rainfall over East Asia (Fig. 9). In Fig. 10, the interannual variability of each index and PC time series of the first EOF mode also are examined, and the PCCs and TCCs for each pattern and interannual variance are described in Table 2. Section 4.1 presents more details on the East Asian Rainfall Index (EARI) in Figs. 9 and 10.

Spatial distribution of a the first EOF mode for the observed precipitation over the East Asia and regressed precipitation (unit: mm day−1) on the normalized, b EASMI, c MPI1, d MPI2 and e EARI. The dashed lines (gray) represent the region of significant values at the 90 % confidence level from a two-tailed Student’s t test

In Table 2, the precipitation patterns regressed on the MPIs are much more similar to the spatial pattern of the first EOF mode of the summer rainfall over East Asia than those on EASMI. The PCC between the spatial patterns associated with the EOF and EASMI is about 0.6, while the regressed patterns on the MPIs have much closer relationships (higher correlation of more than around 0.7) with the EOF1 spatial pattern. The regression pattern of the summer rainfall with respect to the EASMI shows a very similar structure (PCC is more than 0.9) compared to the pattern with respect to MPI2, unlike that to MPI1 which has a correlation close to zero. Figure 10 shows the interannual variability of each index. All indices except for EASMI have variation with a period of 4–5 years (figure not shown). Table 2 also illustrates that the first PC time series of the observed precipitation has a statistically significant and strong correlation with MPI2 (0.75) compared to the EASMI (0.54) and MPI1 (0.49). Furthermore, the relationship between the EASMI and MPI2 implies that the EASMI has a close relationship with the tripole structure, represented as the second EOF mode of the convective activity over the tropical western Pacific, related to the ENSO decaying.

The previous sections have used the observed MPIs produced by the major patterns of the rainfall representing convective activity over the WTP to investigate the relationship of the MPIs with the East Asian monsoon rainfall and the usefulness of the MPIs as the predictors in predicting monsoon rainfall over East Asia. In the next section, an intercomparison is conducted between the observed and predicted MPIs for the individual models and MME.

3.3 Comparison between the observed and simulated convective activity over the WTP

We analyze the interannual variability of the MPIs to determine whether the strong relationship between the observation and the models shown in Fig. 2 also presents in the comparisons between the observed and simulated MPIs indicating the significant feature of the convection over the WTP.

The MPIs produced from the each model and MME forecasts as well as observation are depicted in Fig. 11 and the TCCs between the observation and predictions for MPI1 and MPI2 are shown in Table 3. In general, the patterns of interannual variation of the MPIs obtained from the predictions of the individual models and MME follow a similar distribution to those of the observation (Fig. 11). The TCC results in Table 3 show that the prediction skills for MPI1 for all models and MME, except the NASA model, tend to have higher correlations than those for MPI2. While the prediction skills of the MPIs obtained by the two MSC models show relatively poor performance as compared to those by the other models, the prediction of MPI1 (MPI2) from the APCC (NASA) simulation indicates a considerably high performance of 0.86 (0.83). The performances of the MPIs from MME prediction (0.9 and 0.74 for MPI1 and MPI2, respectively) are generally superior to those from individual models (Table 3).

4 Development of East Asian Rainfall Index (EARI) and skill assessment of the reconstructed rainfall

4.1 East Asian Rainfall Index (EARI)

The previous sections discussed the production and verification of the MPIs representing the main characteristics of convective activity over the WTP and examined the influence of the MPIs on precipitation in the East Asian region. We also investigate the potential feasibility in using of the MPIs as a predictor in terms of rainfall prediction over East Asia. In this section, we develop the EARI by applying the two MPIs to the multiple linear regression method to predict the East Asia summer rainfall. Using the normalized EOF PC1 of observed rainfall over East Asia as a predict and observed normalized MPIs as predictors, the multiple linear regression coefficients are calculated. The EARI representing the EASM rainfall is defined as follows:

The temporal relationship between the developed EARI and EOF PC1 for observed rainfall in East Asia has a considerably higher correlation (more than 0.85 in Table 2; Fig. 10), which is statistically significant at the 99 % confidence level based on Student’s two-tailed t test, and the East Asia summer rainfall regressed onto the EARI shows a significant relationship with the first EOF spatial mode of the observed rainfall (pattern correlation is more than 0.87 in Table 2; Fig. 9e). These results show that, compared to the EASMI and each MPI, the EARI is very closely related to the variation of the observed rainfall over East Asia, and particularly emphasize the necessity of using the two MPIs for the East Asia rainfall prediction. To examine the practicality of the prediction through the verification for the study period of 1983–2005, we use the leave-one-out cross-validation (Michaelsen 1987; Jolliffe and Stephenson 2003; World Meteorological Organization 2006; Lee et al. 2013a, b) for each target year in calculating the cross-validated EARI with normalized observed MPIs. Little difference is evident between the TCCs with the EOF PC1 of observed rainfall over East Asia on the cross-validated EARI (0.848) and EARI (0.855 in Table 2) in observation.

For practical application of the close relationship in observations between the convective activity over the WTP and rainfall over East Asia to the prediction of the individual models and MME, we produce the cross-validated simulated EARI using the regression coefficients obtained in the calculation process of the cross-validated observed EARI and normalized simulated MPIs from the predictions of the MME and individual models. Figure 12 depicts the normalized and cross-validated predicted EARI and EOF PC1 for the observed rainfall in East Asia. In addition, the TCCs between the cross-validated EARIs for individual models and observed PC1 are shown in Table 4. The cross-validated EARI of NASA displays the strongest correlations (0.76) among the models with the observed PC1 time series and there is also no apparent strong relationship between the cross-validated EARIs of the two MSC models and the observed EOF PC1 for rainfall over East Asia due to the lower performance of MPIs in two MSC models. The TCC for cross-validated EARI of the MME shows generally lower performance than that of APCC and NASA. We attribute this to the effect of the two MSC models involved in the MME. For quantitative analysis, the cross-validated simulated EARI of the MME produced by the predictions of the five models, excluding the two MSC models, is compared with the cross-validated EARI of the existing MME. As a result, the correlation for the variability of rainfall in MME except for the lower skilled models is relatively improved (0.66), although not to the expected extent.

4.2 Assessment of the skill of the reconstructed rainfall using EARI

To reconstruct the novel empirical predicted precipitation of each simulation over the East Asia region, the cross-validated predicted EARIs developed from the individual climate model and MME are projected statistically to the observed precipitation pattern regressed onto the cross-validated observed EARI. Figure 13 shows the spatial distributions of prediction skills of each model and MME for the reconstructed precipitation during the period of 1983–2005. In general, the skills of statistical model prediction for precipitation are considerably enhanced, as compared with those of the dynamical model prediction in Fig. 1, over the East Asian region. Particularly, over the land and the vicinity of the Okhotsk Sea, the prediction skills of individual models and MME are notably improved. In addition, the area-averaged TCCs for the statistically reconstructed precipitation of individual models have a relatively better performance of more than 0.1 compared to those for the dynamical prediction of precipitation (table not shown). However, as for the statistical forecast which includes the two MSC models, attaining these improved prediction skills is difficult in the East Asia region due to the relatively poor performance of the EARIs obtained by the MPIs of the two model predictions (see Tables 3, 4). These results negatively affect the reconstructed precipitation using the MME prediction and are expected to reduce the skill enhancement of the MME prediction. Therefore, the eventual enhancement of the prediction performance of individual models should form a basis to overcome the limitations of MME seasonal prediction.

Same as Fig. 1, except for the reconstructed precipitation projected by the normalized and cross-validated EARIs for individual models and MME

In Fig. 14, the skills for the dynamical predicted precipitation of Fig. 3a are compared to those for the statistical reconstructed precipitation by using the scatter diagram between the PCC and NRMSE over East Asia. These results reveal that the skills of the hybrid dynamical–statistical prediction are generally better than those of dynamical prediction, as evidenced by the performance comparison between each model of Figs. 1 and 13. The PCC of the MME prediction by the hybrid dynamical–statistical method shows an improved performance of about 0.1 as compared to that by the dynamical prediction. Furthermore, the difference between the averaged PCC skills of all constituent dynamical and statistical models is similar to the result of the aforementioned MME performance. The distribution toward the lower right side of the PCC and NRMSE of the statistical models demonstrates the considerably improved overall performance in the statistical predictions as compared with the dynamical models.

Scatter diagram between the spatial PCCs and NRMSEs for precipitation of each model and MME derived from dynamical model prediction (DMP, red) and statistical model prediction (SMP, blue) over East Asia. The x (mean of individual models) indicates the average of the PCC (or NRMSE) skills of all constituent models

5 Summary and conclusions

The impact of convective activity in the WTP on East Asian rainfall was investigated to develop a hybrid dynamical–statistical method using the inter-relationship between western Pacific convection and rainfall variance in East Asia. By applying the developed method to the individual models and MME, the summer rainfall over the East Asian region was predicted and the prediction skill was examined.

The model data used in this diagnostic study consisted of seasonal retrospective forecasts for boreal summer (JJA) over the 23-year period (1983–2005) from the seven APCC operational coupled forecast models. The NCEP-DOE reanalysis 2 (Kanamitsu et al. 2002) and CMAP precipitation (Xie and Arkin 1997) were used for the same period as the model data.

The EASM region experiences complex climate variation having wide spatial and temporal spectrum influenced by climate factors originating from both the extra-tropics and the tropics. In this study, we focused on the WTP affecting lower-level moisture transport into East Asia and thus strongly influencing rainfall in East Asia during the boreal summer. Using this relationship, we tried to overcome the limitations of dynamical model prediction for summer precipitation in East Asia.

We examined the characteristics of convection in the western Pacific affecting the East Asian monsoon rainfall and identified two types of distinct structure patterns in the WTP. In our results, the first and second patterns were closely related to ENSO developing and ENSO decaying modes, respectively. Using two distinct patterns, as the major influences on the East Asian summer rainfall, related to western Pacific convection, normalized MPIs were developed. We investigated the inter-relationship in terms of teleconnection patterns for the various variables to assess the possible use of the developed MPIs. Consequently, we found teleconnection patterns with a meridional tripole structure for each variable, which confirmed the suitability of the MPIs in representing the EASM variability. These patterns resembled the well-known PJ and EAP teleconnection patterns. Accordingly, the MPIs are useful predictors for precipitation prediction in the East Asia region. We also found that the regressed precipitation on MPIs and the interannual variability of MPIs had a statistically significant and strong correlation with the pattern and variability of observed precipitation over East Asia.

We selected the PC time series of the first EOF mode for precipitation over East Asia as a predict and two newly developed MPIs as predictors, and used a multiple linear regression method to develop the EARI, which indicates the interannual variability of the East Asian monsoon rainfall. The regressed rainfall pattern from EARI exhibited superior performance to that from the EASMI or each MPI. This result demonstrated the necessity of using these two new MPIs, which represent western Pacific convection, to improve the prediction skill of East Asian precipitation. For practical application to real-time forecasts, we used the leave-one-out cross-validation for each target year of the study period and obtained multiple linear regression coefficients for 23 years by calculating the cross-validated observed EARI. The normalized predicted MPIs obtained from the individual climate model and MME predictions were subjected to multiple regression analysis to produce the cross-validated and predicted EARI. The developed EARIs of the individual climate models and MME were applied statistically to the observed and regressed precipitation pattern to reconstruct the novel empirical predicted precipitation over the East Asia region. We evaluated the reconstructed East Asia summer precipitation of the individual models and MME, and found that the observed characteristics over East Asia are well captured. In general, the predictions of the individual models and MME using the hybrid dynamical–statistical method showed better performance than those of the dynamical models and their MME.

In the present study, the relatively small size of the available hindcast datasets posed a sampling limitation. In addition, we considered only climate factors from the WTP convection for the summer rainfall variability in East Asia, which is a complex area influenced by a variety of spatial and temporal climatic factors. As mentioned in many recent studies (Kwon et al. 2005; Ha et al. 2009; Choi et al. 2010), the trend of the change in rainfall variability over East Asia before and after the mid-1990s may be another potential consideration for seasonal prediction of East Asian monsoon rainfall. Nonetheless, the study methodology enhanced the prediction skill of the reconstructed summer rainfall, produced by the hybrid dynamical–statistical method using the predictors obtained from a statistically significant region. Consequently, the developed method can be applied to the operational seasonal forecast system for further improvement of forecast information. This research also emphasizes that the enhancement of forecasting capabilities of the individual models themselves should take precedence in attempts to improve seasonal prediction, not only in East Asia but worldwide.

References

Ahn JB, Kim HJ (2013) Improvement of one-month lead predictability of the wintertime AO using a realistically varying solar constant for a CGCM. Meteorol Appl. doi:10.1002/met.1372

Choi KS, Moon JY, Kim DW, Byun HR, Kripalani RH (2010) The significant increase of summer rainfall occurring in Korea from 1998. Theor Appl Climatol. doi:10.1007/s00704-010-0256-0

Gong DY, Yang J, Kim SJ, Gao YQ, Guo D, Zhou TJ, Hu M (2011) Spring Arctic oscillation-East Asian summer monsoon connection through circulation changes over the western North Pacific. Clim Dyn 37:2199–2216. doi:10.1007/s00382-011-1041-1

Ha KJ, Yun KS, Jhun JG, Li J (2009) Circulation changes associated with the interdecadal shift of Korean August rainfall around late 1960s. J Geophys Res 114:D04115. doi:10.1029/2008JD011287

Huang G (2004) An index measuring the interannual variation of the East Asian summer monsoon—the EAP index. Adv Atmos Sci 21:41–52

Huang R, Sun F (1992) Impacts of the tropical western Pacific on the East Asia summer monsoon. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 70:243–256

Jeong HI, Ashok K, Song BG, Min YM (2008) Experimental 6-month hindcast and forecast simulation using CCSM3. APCC 2008 technical report, APEC Climate Center

Jolliffe IT, Stephenson DB (2003) Forecast verification: a practitioner’s guide in atmospheric science. Wiley, ISBN: 0-471-49759-2

Kanamitsu M, Ebisuzaki W, Woollen J, Yang SK, Hnilo JJ, Fiorino M, Potter GL (2002) NCEP-DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2). Bull Am Meteorol Soc 83:1631–1643

Kang IS, Jin K, Wang B, Lau KM, Shukla J, Krishnamurthy V, Schubert SD, Wailser DE, Stern WF, Kitoh A, Meehl GA, Kanamitsu M, Galin VY, Satyan V, Park CK, Liu Y (2002) Intercomparison of the climatological variations of Asian summer monsoon precipitation simulated by 10 GCMs. Clim Dyn 19:383–395

Kang H, Park CK, Saji NH, Ashok K (2009) Statistical downscaling of precipitation in Korea using multimodel output variables as predictors. Mon Weather Rev 137:1928–1938

Ke ZJ, Zhang PQ, Chen LJ et al (2011) An experiment of a statistical downscaling forecast model for summer precipitation over China. Atmos Ocean Sci Lett 4:270–275

Kim SJ, Flato GM, Boer GJ (2003) A coupled climate model simulation of the last glacial maximum, part 2: approach to equilibrium. Clim Dyn 20:635–661

Kwon M, Jhun JG, Wang B, An SI, Kug JS (2005) Decadal change in relationship between east Asian and WNP summer monsoons. Geophys Res Lett 32:L16709. doi:10.1029/2005GL023026

Lang XM, Wang HJ (2010) Improving extraseasonal summer rainfall prediction by merging information from GCMs and observations. Weather Forecast 25:1263–1274

Lau KM, Kim KM, Yang S (2000) Dynamical and boundary forcing characteristics of regional components of the Asian summer monsoon. J Clim 13:2461–2482

Lee DY, Tam CY, Park CK (2008) Effects of multicumulus convective ensemble on East Asian summer monsoon rainfall simulation. J Geophys Res 113:D24111. doi:10.1029/2008JD009847

Lee WJ et al (2009) APEC Climate Center for Climate Information Services. APCC 2009 final report. http://www.apcc21.net/eng/research/pub/repo/japcc040602_lst.jsp

Lee JY, Wang B, Kang IS et al (2010) How are seasonal prediction skills related to models’ performance on mean state and annual cycle? Clim Dyn 35:267–283

Lee DY, Ashok K, Ahn JB (2011a) Toward enhancement of prediction skills of multimodel ensemble seasonal prediction: a climate filter concept. J Geophys Res 116:D06116. doi:10.1029/2010JD014610

Lee SS, Lee JY, Ha KJ, Wang B, Schemm J (2011b) Deficiencies and possibilities for long-lead coupled climate prediction of the western North Pacific-East Asian summer monsoon. Clim Dyn 36:1173–1188

Lee DY, Ahn JB, Ashok K, Alessandri A (2013a) Improvement of grand multi-model ensemble prediction skills for the coupled models of APCC/ENSEMBLES using a climate filter. Atmos Sci Lett 14:139–145. doi:10.1002/asl2.430

Lee DY, Ahn JB, Ashok K (2013b) Improvement of multi-model ensemble seasonal prediction skills over East Asian summer monsoon region using a climate filter concept. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 52:1127–1138. doi:10.1175/JAMC-D-12-0123.1

Li C, Lu R, Dong B (2012) Predictability of the western North Pacific summer climate demonstrated by the coupled models of ENSEMBLES. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-011-1274-z

Liang J, Yang S, Hu ZZ, Huang B, Kumar A, Zhang Z (2009) Predictable patterns of the Asian and Indo-Pacific summer precipitation in the NCEP CFS. Clim Dyn 32:989–1001

Lim EP, Hendon HH, Langford S, Alves O (2012) Improvements in POAMA2 for the prediction of major climate drivers and south eastern Australian rainfall. CAWCR Tech. Rep. No. 051. http://www.cawcr.gov.au/publications/technicalreports.php

Lu R (2001) Interannual variability of the summertime North Pacific subtropical high and its relation to atmospheric convection over the warm pool. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 79:771–783

Michaelsen J (1987) Cross-validation in statistical climate forecast models. J Clim Appl Meteorol 26:1589–1600

Nitta T (1987) Convective activities in the tropical western Pacific and their impact on the Northern Hemisphere summer circulation. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 65:373–390

Peng P, Kumar A, van den Dool H, Barnston AG (2002) An analysis of multimodel ensemble predictions for seasonal climate anomalies. J Geophys Res 107:4710. doi:10.1029/2002JD002712

Rienecker MM et al (2008) The GEOS-5 data assimilation system—documentation of versions 5.0.1, 5.1.0, and 5.2.0, NASA technical report series on global modeling and data assimilation, V27

Saha S, Moorthi S, Wu X, Wang J, Nadiga S, Tripp P, Pan HL, Behringer D, Hou YT, Chuang HY, Iredell M, Ek M, Meng J, Yang R, van den Dool H, Zhang Q, Wang W, Chen M (2014) The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J Clim 27:2185–2208. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00823.1

Simmons H, St Laurent L, Jayne S, Weaver A (2004) Tidally driven mixing in a numerical model of the ocean general circulation. Ocean Model. doi:10.1016/S1463-5003(03)00011-8

Spiegel MR, Stephens LJ (2008) Schaum’s outline of theory and problems of statistics, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Sun JQ, Chen HP (2012) A statistical downscaling scheme to improve global precipitation forecasting. Meteorol Atmos Phys 117:87–102

Sun JQ, Wang HJ, Yuan W (2009) A possible mechanism for the co-variability of the boreal spring Antarctic Oscillation and the Yangtze River valley summer rainfall. Int J Climatol 29:1276–1284

Wang B, Fan Z (1999) Choice of South Asian Summer Monsoon Indices. Bull Am Meteorol Sci 80:629–638

Wang HJ, Fan K (2009) A new scheme for improving the seasonal prediction of summer precipitation anomalies. Weather Forecast 24:548–554

Wang B, Xu X (1997) Northern hemisphere summer monsoon singularities and climatological intraseasonal oscillation. J Clim 10:1071–1085

Wang B, Kang IS, Lee JY (2004) Ensemble simulations of Asian-Australian monsoon variability by 11 AGCMs. J Clim 17:803–818

Wang B, Lee JY, Kang IS, Shukla J, Hameed SN, Park CK (2007) Coupled predictability of seasonal tropical precipitation. CLIVAR Exch 12:17–18

Wang B, Lee JY, Kang IS, Shukla J et al (2008a) How accurately do coupled climate models predict the Asian-Australian monsoon interannual variability? Clim Dyn 30:605–619

Wang B, Wu Z, Li J, Liu J, Chang C-P, Ding Y, Wu G (2008b) How to measure the strength of the East Asian summer monsoon. J Clim 21:4449–4463

Wang B, Lee JY, Kang IS, Shukla J et al (2009) Advance and prospectus of seasonal prediction: assessment of the APCC/CliPAS 14-model ensemble retrospective seasonal prediction (1980–2004). Clim Dyn 33:93–117

Wilks DS (1995) Statistical methods in the atmospheric sciences: an introduction. Academic, San Diego

World Meteorological Organization (2006) Standardised verification system (SVS) for long‐range forecasts (LRF): new attachment II‐8 to the manual on the GDPFS, WMO 485, vol I, Geneva, Switzerland, pp 83

Wu B, Zhou T, Li T (2009) Contrast of rainfall–SST relationships in the Western North Pacific between the ENSO-developing and ENSO-decaying summers. J Clim 22:4398–4405. doi:10.1175/2009JCLI2648.1

Xie P, Arkin PA (1997) Global precipitation: a 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge observations, satellite estimates, and numerical model outputs. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 78:2539–2588

Yang S, Zhang Z, Kousky VE, Higgins RW, Yoo SH, Liang J, Fan Y (2008) Simulations and seasonal prediction of the Asian summer monsoon in the NCEP Climate Forecast System. J Clim 21:3755–3775

Zhu C, Park CK, Lee WS et al (2008) Statistical downscaling for multi-model ensemble prediction of summer monsoon rainfall in the Asia-Pacific region using geopotential height field. Adv Atmos Sci 25:867–884. doi:10.1007/s00376-008-0867-x

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the APCC MME Producing Centres for making their hindcast/forecast data available for analysis, the APEC Climate Center for collecting and archiving them and for organizing APCC MME prediction. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2014R1A6A3A01009455), and by the Korea Meteorological Administration Research and Development Program under Grant CATER 2012-3100 and Rural Development Administration Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development under Grant Project No. PJ009353, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D.Y., Ahn, JB. & Yoo, JH. Enhancement of seasonal prediction of East Asian summer rainfall related to western tropical Pacific convection. Clim Dyn 45, 1025–1042 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2343-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2343-x