Abstract

The waste problem in the U.S. has only intensified in recent years, first due to China’s National Sword Policy and then to the COVID-19 pandemic. One solution to this problem is to encourage people to adopt pro-environmental behaviors such as opting for reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging. In this study, we employ the value-belief-norm theory to examine whether its proposed causal chain predicts consumers’ willingness to use reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging. We also explore the moderating role of perceived behavior control, one of the strongest predictors of environmental behaviors. Our research provides support to the value-belief-norm theory in predicting behavioral willingness. The moderating role of perceived behavior control provides additional insight into the theoretical model and furnishes practical implications for strategic communication designed to encourage the adoption of reusables and alternative packaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2018, China, the top importer of U.S. recyclables, implemented the National Sword Policy that restricted the import of certain types of solid waste and set strict contamination limits on recyclable materials. This subsequently led to a 23% increase in landfilled waste in the U.S. (Vedantam et al. 2022). Later, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a steep increase in both organic and inorganic waste (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020; Roe et al. 2021). Looking at the food industry alone, deliveries in the U.S. saw a collective revenue increase of $3 billion (Market Watch 2020), while panic buying resulted in sub-optimal storage of perishables (Roe et al. 2021), both of which contributed to greater waste. Meanwhile, the recycling industry took a substantial hit due to budget constraints (Staub 2020) and a sudden shift in waste management practices (Love and Rieland 2020).

While recycling is one approach to solving the waste problem, it is regarded as an end-of-the-pipe solution that falls lower down in the waste hierarchy (European Union 2008). The waste hierarchy is based on the 4-R’s framework that ranks waste management measures according to their importance in protecting the environment: Reduction, Reuse, Recycling, and Recovery. Compared to recycling, reusing materials and reducing the amount of waste sent to the landfill have well-documented benefits such as avoiding garbage collection and transportation costs (Cooper and Gutowski 2017), as well as reducing the associated environmental pollution (Manfredi and Christensen 2009) and conserving natural resources. Thus, shifting attention to the comparatively less touted strategies for waste management not only aligns well with the U.S Environment Protection Agency’s recognition that “no single waste management approach is suitable for managing all materials and waste streams in all circumstances,” (US EPA 2015) but also fits into its overarching goal of fostering a circular economy in the country (Recycling Today 2021).

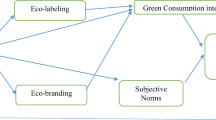

In this study, we examine the social cognitive factors that influence people’s decision to opt for reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging (PAP) using the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory. Even though the theory has fairly strong predictive power in several environmental domains, the linearity of the posited relationships is unclear (Aguilar-Luzón et al. 2012). Meanwhile, the other major theoretical perspective that has been widely recognized to predict environmental behaviors is the theory of planned behavior (TPB). While the TPB explains human behavior as a rational choice based on deliberation across a wide range of contexts (Armitage and Conner 2001), the VBN is specifically developed to predict environmental behavior (Stern et al. 1999). Nevertheless, environmental scholars have highlighted the need for an integrative approach (Steg and Vlek 2009), and several studies have used these two models in conjunction to explain environmental behavior (see, for example, Han 2015; Kaiser et al. 2005). In this study, we examine the influence of perceived behavior control, one of the main constructs of the TPB, on the VBN variables, in predicting behavioral willingness. This decision is driven by the theoretical pursuit to examine the VBN in the context of reusables and PAP, as well as evidence from past literature demonstrating the importance of perceived behavior control in shaping behavioral intention. For instance, studies show that most people maintain a favorable attitude toward recycling and believe it is socially desirable. However, whether people actually engage in recycling often depends on their perceived ability to recycle (Rosenthal 2018). Thus, we expect that perceived behavior control could provide key insights into the relationships proposed in the VBN. Also, if found to be a meaningful predictor of behavioral willingness, perceived behavioral control could serve as a useful audience segmentation tool in designing communication strategies for campaigns seeking to encourage the use of reusables and PAP among members of the public who may or may not find it easy to adopt these materials.

Literature Review

Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory

Stern et al. (1999) proposed the VBN theory that extended the norm activation model (Schwartz 1977) by integrating the value theory (Schwartz 1992) and the new ecological paradigm (Dunlap et al. 2000). The theory presents a causal chain in which relatively stable factors, namely values and environmental concern affect behavior-specific variables (i.e., problem awareness, responsibility ascription, and personal norm), which then influence specific behaviors. Thus, people are likely to perform an environmental behavior when they feel morally obliged to do so. Feelings of moral obligation are stronger when people are aware of the consequences of their environmentally detrimental behavior and feel responsible to avert these undesirable consequences. Further, people are likely to be more aware of the environmentally damaging consequences when they possess a strong level of environmental concern. Lastly, environmental concern is influenced by people’s values. Although values are stable and strong determinants of environmental behavior, they do not influence behavior in a direct way, rather, this influence is mediated by beliefs and norms. Thus, norms are the primary and direct determinant of pro-environmental behavior.

Several studies have provided support for the VBN in explaining specific environmental behaviors. For instance, Fornara and colleagues (2016) found it to be a good fit for predicting the use of renewable energy sources at the household level. Likewise, Onel and Mukherjee (2017) found that recycling behavior was better explained by VBN, relative to other widely used theories such as the theory of planned behavior and the theory on affect (Russell 1980). Results from five European countries provided additional evidence for the theory’s applicability in the sustainable transport domain (de Groot and Steg 2008). Specifically, VBN predicted an acceptable percentage of road pricing as well as the intention to reduce car usage when such a policy was implemented. Having been tested in different countries, the theory also seems to have broad applicability to different cultural contexts (Jakovcevic and Steg 2013).

Environmental Value

Individuals who hold pro-environmental value display a heightened intention to engage in environmental behaviors (van der Werff et al. 2013). Particularly, biospheric values are strongly and consistently related to environmental preferences, intentions, and behaviors (Steg and de Groot 2012). People with biospheric values care for nature and base their decisions about individual behaviors on the consequences these actions would have on the environment (van der Werff et al. 2013). For instance, past research has shown biospheric value to be positively related to support for climate change mitigation (Steg et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2015), sustainable consumption (Thøgersen and Ölander 2002), and a preference for restaurants serving organic food (Steg et al. 2014). In a study by Schultz and Zelezny (1998), for instance, the positive relationship between pro-environmental value and behaviors was evident cross-culturally in a variety of domains ranging from individual actions (e.g., picking up litter, conserving gas by walking or cycling) to policy support (e.g., voting for a candidate who supports environmental issues). Thus, we first propose:

H1: Participants with strong pro-environmental value will have strong beliefs regarding reusables and PAP (H1a) and a strong behavioral willingness to use them (H1b).

See Fig. 1 below for a depiction of the theoretical model with hypotheses.

Beliefs

The beliefs component of VBN includes two constructs, namely awareness of consequences (AC) and ascription of responsibility (AR). While some studies focus on AC and AR beliefs on general environmental conditions (Gärling et al. 2003), others include behavior specific beliefs (Nordlund and Garvill 2003). Klandermans (1992) and Schwartz (1977) argue that for people to be motivated to cooperate in a social dilemma (in this case, the choice between acting to protect the environment or not), they must believe that there are problems that need to be collectively addressed, and their decision to cooperate is relevant to the solution of these problems. Thus, in order for people to opt for reusables and PAP, they must harbor behavior specific beliefs wherein awareness of specific consequences (e.g., waste generated from single-use plastics) and specific perceived responsibility for them (e.g., using a reusable cup for coffee) can help deal with environmental problems. Nordlund and Garvill (2003) tested this argument in the context of reducing personal car usage by quantifying both general awareness (e.g., threat of pollution and energy consumption to the biosphere and humankind) and specific awareness (e.g., degree of influence of car traffic on pollution and energy consumption). Their results indicated that specific awareness of car traffic directly influenced personal norm, which in turn positively predicted willingness to reduce personal car usage, although general awareness was argued to be an important precursor of specific awareness. Thus, behavior specific beliefs were strongly related to behavior (Nordlund and Garvill 2003). Thus, the predictive power of the VBN theory is enhanced when AC and AR are tuned towards a specific behavior (Steg et al. 2005).

The influence of both AC and AR on pro-environmental behaviors is well established. For instance, de Groot and Steg (2009) found that personal norm was stronger when participants were aware of the negative consequences of energy use. Similarly, Harland et al. (2007) found that awareness of consequences positively influences personal norm and household pro-environmental behavior, specifically, public transportation use and water saving. Likewise, in the case of ascription of responsibility, one study indicated that AR significantly contributed to explanation of personal norm and subsequently reduced car usage (de Groot and Steg 2009). Klöckner and Ohms (2009) also found a positive relationship between AR and personal norm when examining purchase of organic milk. In terms of the chain of influence, VBN predicts that AC influences AR, which further impacts personal norm, but the empirical evidence is mixed in this regard. For instance, examining electricity saving behavior, Zhang et al. (2013) found that AC and AR simultaneously and positively influenced personal norm, which in turn affected electricity saving behavior. In another meta-analysis, the model assuming the causal influence of AC on AR and thereafter personal norm showed a poorer fit to the data as compared to an alternative model that specified the simultaneous influence of both AC and AR (Klöckner 2013). Building off these findings, we combine AC and AR into a combined index of beliefs, anticipating that:

H2: Participants with strong beliefs regarding reusables and PAP will feel more personally obligated to use reusables and PAP (H2a) and a strong behavioral willingness to use them (H2b).

Personal Norm

Personal norm or moral norm has been used interchangeably in past literature (Bamberg and Möser 2007). Personal norm is formed by internalized values and refers to an individual’s belief about what is right or wrong so they can maintain a positive self-image (Thøgersen 2006). Several studies have shown that personal or moral norm predicts pro-environmental behaviors such as energy conservation (Black et al. 1985), recycling (Guagnano et al. 1995), and choice of travel mode (Hunecke et al. 2001). According to Bamberg and Möser (2007), personal norm develops as a result of social norm since the latter informs standards of behavior that are considered suitable in a particular situation. When such standards are internalized, they are transformed into personal norm.

It may be important to examine personal norm in certain private-sphere behaviors such as the use of reusables and PAP. As Ajzen (1991) argues, when behavior is related to a moral issue, people may experience a sense of moral obligation, aside from social pressure. Since using reusables and PAP is an altruistic, private behavior with no immediate rewards or benefits to an individual (Hopper and Nielsen 1991), people may engage in this behavior because it is the right thing to do, not because it is socially desirable. Hence, we anticipate that:

H3: Participants who feel more personally obligated to use reusables and PAP will be more likely to use them.

Perceived Behavior Control

Perceived behavior control (PBC; i.e., self-efficacy) refers to a person’s perceived ability to engage in a behavior. Its influence on several pro-environmental behaviors has been well-established, especially as part of the theory of planned behavior (TPB). For instance, Mannetti et al. (2004) found that TPB variables explained a substantial variance in recycling intent, with PBC as one of the most important predictors. Thus, when people lack the requisite skills or resources to perform a behavior, attitude and subjective norm (the other two constructs of TPB) may not predict behavioral intent as well (Yzer 2012). Similar independent effects of PBC on behavioral intent has also been found when examining water conservation (Yazdanpanah et al. 2015) and reduction in car use (Skarin et al. 2019). In another study, researchers investigated behavior adoption (i.e., “currently do”, “could do and planning to”, “could do but don’t”, and “could not do”) related to four types of pro-environmental behaviors – transportation, energy, food, and activism (Lamm et al. 2022). They found that perceived behavioral control was a consistent predictor across all levels and domains. Perceived behavioral control has also been found to be a significant mediator of spillover effect from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, perceived behavior control mediated the transition from easy water conservation behaviors to more difficult actions such as installing water efficient appliances (Lauren et al. 2016).

As part of the TPB, Ajzen (1985) argues that PBC may interact with attitude and subjective norm to influence behavior. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that as an addition to the VBN framework, PBC might also function as a moderator on the relationship between beliefs and personal norm and behavioral willingness. Supporting this conjecture, Luszczynska et al. (2011) maintain that PBC is likely to act as a moderator because people with better skills or resources are likely to be more confident of their behavior, thus being better able to engage in the actual behavior. In a systematic review, Yzer (2012) found that PBC often interacts with attitude and personal norm to influence behavioral intent, although the interaction between perceived behavioral control and attitude is stronger. Looking at past literature, it seems like perceived behavioral control is one of the key variables that influences environmental behaviors both directly and indirectly. Thus, in addition to examining its direct relationship with behavioral willingness, we examine whether the influence of beliefs (conceptualized as awareness of consequences and responsibility attributed to them) on personal norm and behavioral willingness is moderated by PBC. Thus, we propose:

H4: Perceived behavioral control will be positively related to behavioral willingness to use reusables and PAP.

H5: Perceived behavior control will moderate the relationship between beliefs and personal norm (H5a), beliefs and behavioral willingness (H5b), and personal norm and behavioral willingness (H5c).

Material and Methods

Participants

We contracted Ipsos Public Affairs to recruit a representative sample of New York state adult residents (N = 1003). Ipsos Knowledge Panel® is the largest online research panel that is representative of the U.S. population. It uses probability-based sampling to randomly recruit panel members, with the capability to include hard-to-reach populations by providing them Internet and hardware access. The survey began on August 10 and ended on August 29, 2022. The median survey completion time was approximately 20 min.

We had slightly more females (52.3%) than males (47.7%), and the average age was 49.28 (SD = 17.16). The majority of our sample was White (58.4%). Among the respondents, 37.4% (n = 375) received bachelor’s degree or higher, followed by high school (n = 280, 27.9%), some college (n = 267, 26.6%), and less than high school education (n = 81, 8.1%). The median household income was in the bracket of $75,000–$99,999, and most of our respondents (67.1%) were employed. In terms of political ideology, respondents reported middle-of-the-road political ideology (M = 3.93, SD = 1.53, 1 = extremely liberal, 7 = extremely conservative).Footnote 1

Procedure

Selected panel members received an email invitation to complete the survey and were asked to do so at their earliest convenience. The survey was fielded in English. Ipsos fielded 1752 surveys and 1067 were completed, resulting in a completion rate of 60.9%. Among the 1060 surveys, 1003 were qualified, resulting in a qualification rate of 94.0%. As standard with KnowledgePanel® surveys, email reminder was sent to non-responders on Day 3, and an additional reminder was sent to the remaining non-responders on Day 5 of the field period.

Measures

Table 1 shows individual items wording and descriptive statistics of all variables. Table 2 shows the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) analysis, which suggests good discriminant validity among the variables. All items were measured on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Environmental value

To measure environmental value, we used a seven-item subset of the 15-item New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale (Dunlap et al. 2000), which has been widely in past literature (e.g., Feldman and Hart 2018). Sample items included “The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset by human activities” and “We are approaching the limit of the number of people the earth can support.”

Beliefs

Beliefs were measured by quantifying awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility, both adapted from past literature (de Groot and Steg 2009). For AC, responses to items such as “Reusables help to conserve natural resources” and “Reusables prevent waste from going to landfills” were measured. For AR, responses to items such as “Using reusables is a personal choice and it has nothing to do with responsibility to the environment (reverse recoded)” were measured.

Personal norm

Three items were adapted from Park and Ha (2014) to measure personal norm. Participants indicated how morally obligated they felt about using reusables and PAP (e.g., “I feel a strong personal obligation to use reusables when I can”).

Perceived behavior control

For PBC, we used three items adapted from Onel and Mukherjee (2017). Sample items included, “Filling reusable cups or travel mugs at coffee shops is unsanitary (reverse coded)” and “Using reusables is inconvenient (reverse coded).”

Behavioral willingness

Seven items were used to assess participants’ intention to opt for reusables and PAP. Sample items included, “If it were allowed, I would bring a travel mug to be refilled at a coffee shop”, and “I will bring a reusable shopping bag when I go grocery shopping”.

Analysis

Structural equation modeling was conducted in Mplus 8.8 to examine the overall theoretical model. A maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) with robust standard errors was employed to account for potential issue with multivariate normality, although the normality assumption was not violated for any individual observed variable. Two-step modeling verified the measurement model before adding proposed paths to test the structural model (Kline, 2005). All standardized factor loadings in the measurement model were above 0.50. However, the model fit improved significantly when we allowed the first two items that measured environmental value to correlate. Indicators of model fit included chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI; values close to or greater than 0.92), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; values close to or greater than 0.92), root mean square error approximation (RMSEA; values lower than 0.05), and standardized root mean residual (SRMR; values lower than 0.06) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We did not include demographic variables in model testing due to the lack of consensus on how to include control variables in a theoretical model. To address the moderation hypothesis, we used PROCESS macro model 59.

Results

Table 3 shows model fit indices for the measurement model and the structural model, all of which suggest good fit to the data. For the ease of interpretation, Fig. 2 shows the standardized regression coefficients for significant paths in the structural equation model. Overall, the proposed theoretical model accounts for about 46% of the variance in beliefs, 65% of the variance in personal norm, and 75% of the variance in behavioral willingness.

The first hypothesis proposed a positive relationship between pro-environmental value and beliefs (H1a), as well as between pro-environmental value and behavioral willingness (H1b). We found that people who had strong pro-environmental value were likely to have stronger beliefs pertaining to reusables and PAP (β = 0.67, p < 0.001). They were also more likely to use them (β = 0.14, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 was supported.

Next, we proposed a positive relationship between beliefs and personal norm (H2a), as well as beliefs and behavioral willingness to use reusables and PAP (H2b). We found that people who have strong beliefs were likely to feel more personally obligated to use reusables and PAP (β = 0.81, p < 0.001). They were also more likely to use them (β = 0.24, p < 0.01). Thus, H2 was also supported.

In our next hypothesis, we proposed that people who felt more personally obligated to use reusables and PAP would be more likely to use them. We found that this was indeed the case; people who reported stronger personal norm showed higher behavioral willingness to use reusables and PAP (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). Thus, H3 was supported.

Lastly, we found a significant relationship between perceived behavioral control and behavioral willingness to use reusables and PAP (β = 0.38, p < 0.001), supporting H4. Regarding the moderation effect stated in the final hypothesis, we only found a significant moderation effect of perceived behavioral control on the relationship between personal norm and behavioral willingness (β = −0.11, p < 0.001). Specifically, high perceived behavior control diminishes the importance of personal norms in forming behavioral willingness, even though the overall relationship between personal norms and behavioral willingness is positive. However, the strength of the relationship between beliefs and personal norms, as well as beliefs and behavioral willingness is not affected by perceived behavior control. Thus, H5 was partially supported.

Discussion

In this study, we employ the VBN model to determine consumers’ willingness to adopt reusables and PAP. Specifically, we explore whether values, beliefs, and norms are related to behavioral willingness, while also exploring the moderating role of perceived behavior control on these relationships. Results indicate support for most of the hypothesized relationships.

First, environmental value was positively related to beliefs conceptualized by awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility. In other words, when people are concerned about the environment, they are more likely to be aware of the ill-effects of environmentally detrimental behaviors (such as not using reusables and PAP) and feel responsible for avoiding these consequences. Strong environmental concern is also positively associated with behavioral willingness to adopt reusables and PAP. These findings are unsurprising and in line with past literature (Schultz and Zelezny 1998; Steg et al. 2014; Thøgersen and Ölander 2002; Yang et al. 2015).

Furthermore, strong beliefs not only heighten people’s sense of moral obligation to opt for reusables and PAP but also encourage them to opt for them. These findings are supported by previous work that shows that moral obligation originates from a simultaneous influence of problem awareness and an ascription of responsibility (de Groot and Steg 2009). In other words, beliefs induce a sense of moral obligation among people (Klöckner 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). The positive relationship of beliefs with environmental behavior has also been evidenced before (Nordlund and Garvill 2003).

Next, personal norm is the immediate determinant of behavioral willingness, supporting the VBN theory and past empirical work (Bamberg and Möser 2007; Zhang et al. 2017). Research has shown that framing environmental behaviors such as recycling as a moral issue can motivate people to recycle (Chan and Bishop 2013). In our study, the adoption for reusables and PAP could be seen as prosocial, moral behaviors based on what is right or wrong for the environment. Thus, the role of personal norm in activating pro-environmental behavior is unsurprising. Having said that, this behavior may not just be dependent on one’s internalized moral obligation to do the right thing; other variables such as subjective norm (Al-Swidi et al., 2014; Read et al. 2013) and emotions (Rezvani et al. 2017; Wang & Wu, 2016) may also influence the relationships proposed in the VBN. Thus, future research should explore these variables to fine tune communication pertaining to reusables and PAP.

Our study exemplifies a strong positive relationship between perceived behavioral control and the willingness to adopt reusables and PAP, which is consistent with existing literature related to other pro-environmental behaviors (Skarin et al. 2019; Yazdanpanah et al. 2015). Further, perceived behavior control moderates the relationship between personal norm and behavioral willingness. When people perceive higher levels of ability to adopt reusable and PAP, personal norm has a relatively weaker impact on behavioral willingness, although the relationship between personal norm and behavioral willingness is consistently in the positive direction. Thus, when people believe themselves as skilled or capable to adopt reusables and PAP, moral obligation is not as crucial a factor in behavioral formation. In contrast, when people feel less confident in their ability to adopt reusables and PAP, moral obligation is a stronger determinant of behavioral willingness. Interestingly, perceived behavioral control did not moderate the relationship between beliefs and personal norm, or the relationship between beliefs and behavioral willingness. Because beliefs, like environmental value, are relatively stable and long-lasting, it makes sense that the impact of beliefs on personal norm and behavioral willingness is not contingent on perceived behavioral control. This result has been evidenced in past research related to recycling (Liu et al. 2022). Specifically, Liu et al. (2022) argue that people with crystallized beliefs about recycling are likely to recycle regardless of their perceived ability to do so. Likewise, when people hold strong beliefs about reusables and PAP, perceived behavioral control does not seem to influence the extent to which these beliefs influence their behavioral adoption.

Theoretically, our work provides evidence of the linearity of the relationships proposed in the VBN theory for a relatively novel and unfamiliar behavior (i.e., using reusables), which could later be extended to other similar pro-environmental behaviors. Moreover, by including PBC in our model, the predictive power of the model is enhanced, which now explains a significant portion of beliefs (R2 = 0.46), personal norm (R2 = 0.65), and behavioral willingness (R2 = 0.75). This addition also demonstrates that the relative impact of personal norm is contingent on perceived behavioral control. In terms of practical implications, communication campaigns may benefit from emphasizing the negative environmental consequences of not using reusables and PAP and the responsibility people have as consumers to be more mindful of their choices. Highlighting the use of reusables and PAP as a moral issue may work particularly well because there is limited information in the public domain pertaining to these products. Furthermore, the moderating influence of perceived behavioral control suggests that people’s perceived ability to adopt reusables and PAP may serve as an important audience segmentation strategy when implementing communication campaigns. Specifically, among people who may perceive themselves as less capable to adopt these products, it may be more important to highlight the fact that this is a moral behavior/the right thing to do. Thereafter, when people’s abilities are enhanced and there are more opportunities to use reusables and PAP, the moral messaging may not be as important. Previous research has shown support for the efficacy of this audience segmentation strategy. For instance, Kumar and Smith (2018) found that different audiences experience different levels of social pressure due to which their intent to purchase local food also vary. The researchers argue that marketers need to utilize social influence (among the group of people most sensitive to it) in order to increase the purchase of local food. Thus, announcing new farm locations/events or asking consumers in this group to share their local food purchase on social media channels could encourage local food buying behavior. Likewise, in areas where there are limited opportunities to use reusables and PAP, different stakeholders (including state and local governments, policy makers, businesses, non-profits, advocacy organizations, residents in their own communities, institutions and schools) may be able to encourage their use by emphasizing the ethical and moral value of such behavior. Simultaneously, stakeholders should continue to provide people with skills and resources to use reusables and PAP and reduce waste from single-use items with ease (e.g., strategically placing signs at food service establishments reminding people to bring their own travel mug, or allowing customers to opt out of automatically being provided single-use items for takeout orders)) so that moral messaging is not required in due course.

While discussing our results, it is important to point out limitations. First, this study relies on self-report survey data that may suffer from social desirability bias that is known to negatively impact survey results (Larson 2019). Future research may benefit from incorporating macro-level consumer data on the adoption of reusables and PAP to assess actual behavior. Second, we measured perceived behavior control, future research may also consider measuring actual control or barriers for adoption such as opportunities to use reusables and price of PAP, which may influence behaviors differently. Lastly, we only focused on New York state residents in this research due to a ban on specific plastic items, such as plastic bags and foam containers in the state. Future research should examine the adoption of reusables and PAP across the nation.

Conclusion

We examine the Value-Belief-Norm theory to determine people’s willingness to adopt reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging. Our results indicate that personal norm is the immediate predictor of behavioral willingness, which is in turn shaped by environmental value and beliefs. Thus, encouraging the use of reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging by highlighting it as a moral issue may serve as a good campaign strategy. We also found that the importance of personal norm in shaping behavioral willingness is dependent on people’s perceived capability to use such products. Thus, in communication strategies and campaigns about reusables and PAP, perceived behavior control should be used as an audience segmentation strategy whereby using reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging can be highlighted as a morally right thing to do in the initial stage of behavioral formation. Thereafter, when being morally driven may become relatively less important, more emphasis should be placed on enhancing people’s ability and providing them with better opportunities to use reusables and products with plastic-free alternate packaging.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Our sample demographics are largely in line with the 2021 American Community Survey statistics.

References

Aguilar-Luzón MDC, García-Martínez JMÁ, Calvo-Salguero A, Salinas JM (2012) Comparative study between the theory of planned behavior and the value–belief–norm model regarding the environment, on Spanish housewives’ recycling behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 42(11):2797–2833. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00962.x

Ajzen I (1985) From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Kuhl J & Beckmann J (eds), Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Swidi A, Huque SMR, Hafeez MH, Shariff MNM (2014) The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br Food J 116(10):1561–1580. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2013-0105

Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 40(4):471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

Bamberg S, Möser G (2007) Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J Environ Psychol 27(1):14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002

Black JS, Stern PC, Elworth JT (1985) Personal and contextual influences on househould energy adaptations. J Appl Psychol 70:3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.3

Chan L, Bishop B (2013) A moral basis for recycling: extending the theory of planned behaviour. J Environ Psychol 36:96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.010

Cooper DR, Gutowski TG (2017) The environmental impacts of reuse: a review. J Ind Ecol 21(1):38–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12388

De Groot JIM, Steg L (2008) Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: how to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ Behav 40(3):330–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506297831

De Groot JIM, Steg L (2009) Morality and prosocial behavior: the role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J Soc Psychol 149(4):425–449. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449

Dunlap RE, Liere KDV, Mertig AG, Jones RE (2000) New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: a revised NEP scale. J Soc Issues 56(3):425–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

European Union. (2008). Directive 2008/98/EC. Official Journal of the European Union. http://eur.lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008L0098

Feldman L, Hart PS (2018) Is there any hope? How climate change news imagery and text influence audience emotions and support for climate mitigation policies. Risk Anal 38(3):585–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12868

Fornara F, Pattitoni P, Mura M, Strazzera E (2016) Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: the role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. J Environ Psychol 45:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.001

Gärling T, Fujii S, Gärling A, Jakobsson C (2003) Moderating effects of social value orientation on determinants of proenvironmental behavior intention. J Environ Psychol 23(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00081-6

Guagnano GA, Stern PC, Dietz T (1995) Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: a natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ Behav 27(5):699–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916595275005

Han H (2015) Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour Manag 47:164–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.014

Harland P, Staats H, Wilke HAM (2007) Situational and personality factors as direct or personal norm mediated predictors of pro-environmental behavior: questions derived from norm-activation theory. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 29(4):323–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701665058

Hopper JR, Nielsen JM (1991) Recycling as altruistic behavior: normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ Behav 23(2):195–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916591232004

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling: Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hunecke M, Blöbaum A, Matthies E, Höger R (2001) Responsibility and environment: ecological norm orientation and external factors in the domain of travel mode choice behavior. Environ Behav 33(6):830–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973269

Jakovcevic A, Steg L (2013) Sustainable transportation in Argentina: values, beliefs, norms and car use reduction. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav 20:70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2013.05.005

Kaiser FG, Hübner G, Bogner FX (2005) Contrasting the theory of planned behavior with the value-belief-norm model in explaining conservation behavior1. J Appl Soc Psychol 35(10):2150–2170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02213.x

Klandermans B (1992) Persuasive communicatio: measures to overcome real-life social dilemmas. In: Liebrand WBG, Messick DM, Wilke HAM (Eds.) Social dilemmas: Theoretical issues and research findings. Pergamon, Oxford, p 307–318. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203769560-27

Kline RB (2005) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Second Edition. Guilford Publications

Klöckner CA (2013) A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob Environ Change 23(5):1028–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.014

Klöckner CA, Ohms S (2009) The importance of personal norms for purchasing organic milk. Br Food J 111(11):1173–1187. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700911001013

Kumar A, Smith S (2018) Understanding local food consumers: theory of planned behavior and segmentation approach. J Food Prod Mark 24(2):196–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2017.1266553

Lamm AE, McCann RGH, Howe PD (2022) I could but I don’t: What does it take to adopt pro-environmental behaviors in the United States? Energy Res Soc Sci 93:102845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102845

Larson RB (2019) Controlling social desirability bias. Int J Mark Res 61(5):534–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785318805305

Lauren N, Fielding KS, Smith L, Louis WR (2016) You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. J Environ Psychol 48:191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.10.004

Liu Z, Yang JZ, Clark SS, Shelly MA (2022) Recycling as a planned behavior: the moderating role of perceived behavioral control. Environ Dev Sustain 24(9):11011–11026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01894-z

Love BJ & Rieland J (2020) COVID-19 is laying waste to many US recycling programs. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/covid-19-is-laying-waste-to-many-us-recycling-programs-139733

Luszczynska A, Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Mazurkiewicz M (2011) Self-efficacy as a moderator of the planning–behaviour relationship in interventions designed to promote physical activity. Psychol Health 26(2):151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.531571

Manfredi S, Christensen TH (2009) Environmental assessment of solid waste landfilling technologies by means of LCA-modeling. Waste Manag 29(1):32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.02.021

Mannetti L, Pierro A, Livi S (2004) Recycling: Planned and self-expressive behaviour. J Environ Psychol 24(2):227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.01.002

Market Watch (2020) The pandemic has more than doubled food-delivery apps’ business. Now what? Market Watch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-pandemic-has-more-than-doubled-americans-use-of-food-delivery-apps-but-that-doesnt-mean-the-companies-are-making-money-11606340169

Nordlund AM, Garvill J (2003) Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J Environ Psychol 23(4):339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00037-9

Onel N, Mukherjee A (2017) Why do consumers recycle? A holistic perspective encompassing moral considerations, affective responses, and self-interest motives. Psychol Mark 34(10):956–971. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21035

Park J, Ha S (2014) Understanding consumer recycling behavior: combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam Consum Sci Res J 42(3):278–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12061

Read DL, Brown RF, Thorsteinsson EB, Morgan M, Price I (2013) The theory of planned behaviour as a model for predicting public opposition to wind farm developments. J Environ Psychol 36:70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.001

Recycling Today (2021) EPA releases National Recycling Strategy. Recycling Today. https://www.recyclingtoday.com/news/epa-national-recycling-strategy-circular-economy-environmental-justice/

Rezvani Z, Jansson J, Bengtsson M (2017) Cause I’ll feel good! An investigation into the effects of anticipated emotions and personal moral norms on consumer pro-environmental behavior. J Promot Manag 23(1):163–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2016.1267681

Roe BE, Bender K, Qi D (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on consumer food waste. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 43(1):401–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13079

Rosenthal S (2018) Procedural information and behavioral control: longitudinal analysis of the intention-behavior gap in the context of recycling. Recycling 3(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling3010005

Russell JA (1980) A circumplex model of affect. J Personal Soc Psychol 39:1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

Schultz PW, Zelezny LC (1998) Values and proenvironmental behavior: a five-country survey. J Cross Cult Psychol 29(4):540–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022198294003

Schwartz SH (1977) Normative influences on altruism. In Berkowitz L (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 221–279). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5

Schwartz SH (1992) Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 Countries. In Zanna MP (ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Skarin F, Olsson LE, Friman M, Wästlund E (2019) Importance of motives, self-efficacy, social support and satisfaction with travel for behavior change during travel intervention programs. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav 62:451–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.02.002

Staub C (2020) Budget shortfalls threaten local recycling programs—Resource Recycling. Resource Recycling News. https://resource-recycling.com/recycling/2020/05/27/budget-shortfalls-threaten-local-recycling-programs/

Steg L, Dreijerink L, Abrahamse W (2005) Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: a test of VBN theory. J Environ Psychol 25(4):415–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.08.003

Steg L, & de Groot JIM (2012) Environmental Values. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0005

Steg L, Groot JIMD, Dreijerink L, Abrahamse W, Siero F (2011) General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: the role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Soc Nat Resour 24(4):349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903214116

Steg L, Perlaviciute G, van der Werff E, Lurvink J (2014) The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ Behav 46(2):163–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512454730

Steg L, Vlek C (2009) Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: an integrative review and research agenda. J Environ Psychol 29(3):309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

Stern PC, Dietz T, Abel T, Guagnano GA, Kalof L (1999) A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: the case of environmentalism. Hum Ecol Rev 6(2):17

Thøgersen J (2006) Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: an extended taxonomy. J Environ Psychol 26(4):247–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.09.004

Thøgersen J, Ölander F (2002) Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: a panel study. J Econ Psychol 23(5):605–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00120-4

US EPA O (2015) Sustainable Materials Management: Non-Hazardous Materials and Waste Management Hierarchy [Collections and Lists]. https://www.epa.gov/smm/sustainable-materials-management-non-hazardous-materials-and-waste-management-hierarchy

van der Werff E, Steg L, Keizer K (2013) The value of environmental self-identity: the relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J Environ Psychol 34:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.12.006

Vedantam A, Suresh NC, Ajmal K, Shelly M (2022) Impact of China’s national sword policy on the U.S. landfill and plastics recycling industry. Sustainability 14(4):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042456

Wang J, Wu L (2016) The impact of emotions on the intention of sustainable consumption choices: evidence from a big city in an emerging country. J Clean Prod 126:325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.119

Yang ZJ, Seo M, Rickard LN, Harrison TM (2015) Information sufficiency and attribution of responsibility: predicting support for climate change policy and pro-environmental behavior. J Risk Res 18(6):727–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2014.910692

Yazdanpanah M, Feyzabad FR, Forouzani M, Mohammadzadeh S, Burton RJF (2015) Predicting farmers’ water conservation goals and behavior in Iran: a test of social cognitive theory. Land Use Policy 47:401–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.04.022

Yzer M (2012) Perceived behavioral control in reasoned action theory: a dual-aspect interpretation. ANN Am Acad Political Soc Sci 640(1):101–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716211423500

Zambrano-Monserrate MA, Ruano MA, Sanchez-Alcalde L (2020) Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci Total Environ 728:138813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138813

Zhang X, Geng G, Sun P (2017) Determinants and implications of citizens’ environmental complaint in China: integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J Clean Prod 166:148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.020

Zhang Y, Wang Z, Zhou G (2013) Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: an empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy 62:1120–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.036

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the larger project undertaken by the New York State Center for Plastics Recycling, Research, & Innovation at the University at Buffalo, a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) supported center. The center seeks to enhance plastics recycling in New York State, reduce contamination in the recycling stream, understand residents’ knowledge and attitudes about recycling and reuse, study plastics in the natural environment, and develop new recycling technologies. Funding for the New York State Center for Plastics Recycling, Research, and Innovation is provided from the Environmental Protection Fund as administered by the NYSDEC. The authors acknowledge useful discussions with Dr. Amit Goyal at the New York State Center for Plastics Recycling, Research and Innovation, and Amy Bloomfield as well as Kayla Montanye at NYSDEC.

Author Contributions

PS: writing – original draft, conceptualization, methodology. JZY: writing – reviewing and editing, methodology, supervision.

Funding

Funding for the New York State Center for Plastics Recycling, Research, and Innovation, a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) supported center, is provided from the Environmental Protection Fund as administered by NYSDEC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All protocols were approved by the IRB at the University at Buffalo and all participants were treated in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants also consented to publishing their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, P., Yang, J.Z. It Takes Two to Tango: How Ability and Morality Shape Consumers’ Willingness to Refill and Reuse. Environmental Management 73, 311–322 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01828-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01828-7