Abstract

Rationale

Research on psychedelics has recently shown promising results in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders, but relatively little remains known about the psychiatric risks associated with naturalistic use of psychedelics.

Objective

The objective of the current study was to investigate associations between naturalistic psychedelic use and psychiatric risks.

Methods

Using a sample representative of the US adult population with regard to sex, age, and ethnicity (N=2822), this study investigated associations between lifetime naturalistic psychedelic use, lifetime unusual visual experiences, and past 2-week psychotic symptoms.

Results

Among respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use (n=613), 1.3% reported having been told by a doctor or other medical professional that they had hallucinogen persisting perception disorder. In covariate-adjusted linear regression models, lifetime psychedelic use was associated with more unusual visual experiences at any point across the lifetime, but no association was observed between lifetime psychedelic use and past 2-week psychotic symptoms. There was an interaction between lifetime psychedelic use and family (but not personal) history of psychotic or bipolar disorders on past 2-week psychotic symptoms such that psychotic symptoms were highest among respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use and a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and lowest among those who reported lifetime psychedelic use and no family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders.

Conclusions

Although the results in this study should be interpreted with caution, the findings suggest that lifetime naturalistic use of psychedelics might be associated with more unusual visual experiences across the lifetime, as well as more psychotic symptoms in the past 2 weeks for individuals with a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and the reverse for those without such a family history. Future research should distinguish between different psychotic and bipolar disorders and should also utilize other research designs (e.g., longitudinal) and variables (e.g., polygenic risk scores) to better understand potential cause-and-effect relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Research on psychedelics such as psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) has recently shown promising results in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders (Andersen et al. 2021; Galvão-Coelho et al. 2021). For example, in a recent double-blind randomized, controlled trial with patients who had been diagnosed with moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder, psilocybin-assisted therapy was at least as effective as an active control condition (escitalopram) in reducing depressive symptoms (Carhart-Harris et al. 2021; see also, Goodwin et al. 2022; von Rotz et al. 2023). The evidence to date suggests that psychedelics generally have a favorable safety profile (Roscoe and Lozy 2022), but psychedelic trials are characterized by strict exclusion criteria and relatively little remains known about the range of possible adverse events (Schlag et al. 2022). It is therefore important to further investigate potential risks associated with psychedelic use, especially among populations that are typically excluded from participation in psychedelic trials (e.g., personal or family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders; Johnson et al. 2008).

One potential risk associated with psychedelic use is visual hallucinations or flashback-type experiences (e.g., halos around objects, macropsia, micropsia) occurring after the acute pharmacological effects have subsided (Baggott et al. 2011; Müller et al. 2022; but see Krebs and Johansen 2013). Such experiences can be diagnosed as hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD; Halpern and Pope Jr 2003) if (1) the visual phenomena persist and cause significant distress or impairment in daily functioning and (2) other medical or psychiatric conditions can be ruled out (American Psychiatric Association 2013; see Halpern et al. 2016 for proposed HPPD subtypes). Yet, the evidence on the prevalence and predictors of unusual visual experiences and HPPD-like symptoms remains relatively limited.

Another concern is that psychedelic use might in rare cases provoke the onset of prolonged psychosis (Strassman 1984), but the evidence has been mixed so far. For example, having used psychedelics five or more times in the past was associated with lifetime experience of two or more psychotic symptoms, in a representative community sample of adolescents and young adults in Germany (Kuzenko et al. 2011). Another study, by contrast, found no association between lifetime psychedelic use and two or more psychotic symptoms in the past year, in a nationally representative sample of adults in the USA (Krebs and Johansen 2013; see also Lebedev et al. 2021). The differences in results across studies may be explained by the heterogeneous research designs, but these studies also did not investigate whether the association between psychedelic use and psychotic symptoms was stronger in populations with a genetic risk for certain psychiatric disorders (e.g., psychotic or bipolar disorders), which could provide insight into the potential risks associated with psychedelic use for these populations.

It is not ethically tenable to experimentally test if, for whom, and under what circumstances psychedelic use may have potentially harmful effects (e.g., HPPD-like symptoms, psychotic symptoms), which highlights the need for epidemiological research on potential psychiatric risks associated with the use of psychedelics. Using a sample representative of the US adult population with regard to sex, age, and ethnicity (N=2822), the objective of the current study was to investigate associations between naturalistic psychedelic use, unusual visual experiences, and psychotic symptoms.

Methods

Participants and procedure

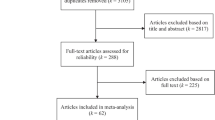

Using linear multiple regression in GPower 3.1 (Faul et al. 2009), it was determined that a sample size of 395 psychedelic users would achieve 80% power to detect a small effect size (Cohen’s f2 of .02) with an alpha of .05. Based on recent data on the prevalence of lifetime psychedelic use in the US adult population (~14%; Simonsson et al. 2021), we estimated approximately 2800 participants would be necessary to obtain 395 psychedelic users in the sample. We aimed to recruit 2800 participants in total.

Participants were current residents of the USA (≥18 years old) and were recruited on Prolific Academic (https://app.prolific.co). The sample (N=2822) was collected in October (1st–9th) 2021 and was stratified across three demographic characteristics—sex, age, and ethnicity—to reflect the demographic distribution of the US adult population. The participants were asked about demographic characteristics, substance use (including psychedelics), unusual visual experiences, and psychotic symptoms. Study completion resulted in $2.20 payment and study procedures were determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The data and Stata syntax are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24316432.v1.

Measures

Demographics and substance use

All respondents were asked to report age in years, gender, ethnoracial identity, educational attainment, annual household income, marital status, engagement in risky behavior, and lifetime use of cocaine, sedatives, pain relievers, marijuana, phencyclidine (PCP), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA/ecstasy), and inhalants.

Lifetime psychedelic use

All respondents were asked to report which, if any, of the following psychedelics they had ever used: ayahuasca, N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), LSD, mescaline, peyote, or San Pedro, or psilocybin. Respondents who reported that they had used any of these substances were coded as 1, whereas those indicating that they had never used any of these substances were coded as 0.

Unusual visual experiences

All respondents completed the 9-item unusual visual experiences scale (Baggott et al. 2011), which asks respondents to report if they have ever had any of the listed unusual visual experiences (e.g., “Stationary things appear to move, breathe, grow, or shrink”), excluding times when they were intoxicated or had used drugs in the past 3 days and times when they were in trance, falling asleep, waking up, or had not been sleeping for a long time. Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate (alpha = .80). The total score was calculated by summing across items. Similar to Baggott et al. (2011), respondents who endorsed any of the first seven listed unusual visual experiences were asked about the frequency of those experiences (very rarely, rarely, occasionally, very frequently, constantly) and also whether these unusual visual experiences overall had been so troublesome or had made social, work, school, or other activities so difficult that they had considered or sought professional treatment (treatment not considered, treatment considered, treatment sought).

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD)

All respondents were asked whether a doctor or other medical professional had ever told them that they had HPPD (yes = 1, no = 0).

Psychotic symptoms

All respondents completed the 6-item psychotic ideation subscale of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ; Zimmerman and Mattia 2001), which asks respondents to report psychotic symptoms during the past 2 weeks (e.g., “During the past two weeks, did you think that you had special powers other people didn’t have?”). Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate (alpha = .69). The total score was calculated by summing across items.

Personal and family history of psychotic disorders, or bipolar disorders I or II

All respondents were asked to report whether they had a current or past history of any psychotic disorders or bipolar I or II disorders, as well as whether they had a first- or second-degree relative with any psychotic disorders or bipolar I or II disorders. For personal history, respondents who reported that they had a current or past history of any psychotic or bipolar disorders were coded as 1, whereas those indicating that they did not have a current or past history of any psychotic or bipolar disorders were coded as 0. For family history, respondents who reported they had a first- or second-degree relative with any psychotic or bipolar disorders were coded as 1, whereas those indicating that they did not have a first- or second-degree relative with any psychotic or bipolar disorders were coded as 0.

Statistical analyses

We used Pearson’s chi-squared tests (for categorical variables) and t-tests (for continuous variables) to examine unadjusted differences between the two groups (users, non-users). Two separate multiple linear regression models were then used to evaluate associations of lifetime psychedelic use (the independent variable in both models) with unusual visual experiences (the dependent variable in model 1) and psychotic symptoms (the dependent variable in model 2). A third multiple linear regression model (model 3) evaluated the interaction between lifetime psychedelic use and personal history of psychotic or bipolar disorders on psychotic symptoms. The purpose of this model was to determine whether psychedelic use might aggravate psychotic symptoms, although the temporal relationship between age of first psychedelic use and age of diagnosis was not investigated. A fourth multiple linear regression model (model 4) evaluated the interaction between lifetime psychedelic use and family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders on psychotic symptoms. The purpose of the fourth model was to determine whether psychedelic use might be more strongly associated with psychotic symptoms among those genetically predisposed to psychotic or bipolar disorders. As sensitivity analyses, we also ran all four analyses using multiple logistic regression models with the dependent variables dichotomized (i.e., one or more unusual visual experiences = 1, no unusual visual experiences = 0; one or more psychotic symptoms = 1, no psychotic symptoms = 0).

In all models, we controlled for broadly the same covariates that were used in the only prior study that has evaluated the associations between lifetime psychedelic use, unusual visual experiences, and psychotic symptoms in a sample representative of the US adult population (Krebs and Johansen 2013): age in years, gender, ethnoracial identity, educational attainment, annual household income, marital status, engagement in risky behavior, and lifetime use of cocaine, sedatives, pain relievers, marijuana, phencyclidine (PCP), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA/ecstasy), and inhalants (each drug use variable entered as a separate covariate). Due to a data collection error, not all covariates in Krebs and Johansen (2013) were included in this study (e.g., lifetime exposure to an extremely stressful event). For all analyses, p-values are reported with 3 decimal places, allowing the reader to estimate any p-value corrections of the reader’s choosing.

Results

Descriptive statistics and sample characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show descriptive statistics and sample characteristics. As seen in Table 1, respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use had significantly higher scores on unusual visual experiences across the lifetime than those who did not report previous psychedelic use, but there were no differences in past 2-week psychotic symptoms between those who reported lifetime psychedelic use and those who did not (see Supplemental Table 1 for additional descriptive statistics). As shown in Table 2, personal and family histories of psychotic or bipolar disorders were significantly more common among psychedelic users. Notably, having been told by a doctor or other medical professional that they had HPPD was significantly more common among psychedelic users (1.3% versus 0.3% among non-users), but no differences were observed across groups in frequency or treatment of unusual visual experiences.

Covariate-adjusted regression models

Table 3 presents results from four separate multiple linear regression models on the associations of lifetime psychedelic use with unusual visual experiences and psychotic symptoms. While lifetime psychedelic use was associated with more unusual visual experiences at any point across the lifetime, no association was observed between lifetime psychedelic use and recent psychotic symptoms. There was an interaction between lifetime psychedelic use and family (but not personal) history of psychotic or bipolar disorders on psychotic symptoms such that psychotic symptoms were highest among respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use and a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and lowest among those who reported lifetime psychedelic use and no family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders (see Supplemental Table 2 for adjusted means). Sensitivity analyses showed broadly the same results (see Supplemental Table 3 for results).

Discussion

The present study investigated the associations between lifetime naturalistic psychedelic use, lifetime unusual visual experiences, and past 2-week psychotic symptoms in a sample representative of the US adult population with regard to sex, age, and ethnicity. Although the results in this study should be interpreted with caution, the findings suggest that lifetime use of psychedelics might be associated with more unusual visual experiences across the lifetime, as well as more psychotic symptoms in the past 2 weeks for individuals with a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and the reverse for those without such a family history.

Lifetime psychedelic use was associated with unusual visual experiences at any point across the lifetime. While such experiences may not have been functionally impairing, the results showed that 1.3% of respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use had been told by a doctor or other medical professional that they had HPPD. Previous research on lifetime users of psychedelics and other substances (e.g., cannabis, ketamine, MDMA) found that at least 1.7% of respondents had a clear temporal relationship between drug use and onset of HPPD-like symptoms (Baggott et al. 2011), which is a statistic that broadly corresponds with the HPPD prevalence reported in this study. Given that potential risk factors (e.g., genetic, extra-pharmacological) of these types of experiences are not yet well-understood, future studies should use longitudinal research designs to better understand if, for whom, and under what circumstances psychedelic use might lead to unusual visual experiences.

Lifetime psychedelic use was not directly associated with recent psychotic symptoms, but there was an interaction between lifetime psychedelic use and family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders on psychotic symptoms such that psychotic symptoms were highest among respondents who reported lifetime psychedelic use and a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and lowest among those who reported lifetime psychedelic use and no family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders. These findings suggest that there may be a genetic predisposition that puts certain individuals at risk of psychotic symptoms following use of psychedelics, which corresponds with the leading guidelines for psychedelic research (Johnson et al. 2008). Previous research suggests that psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are genetically related to bipolar disorders (Ruderfer et al. 2018), but it is possible that the effects of psychedelic use on psychotic symptoms might differ between these disorders. It is also possible that psychedelics can induce a manic switch and put certain individuals at risk of mania (potentially with psychotic features; Gard et al. 2021), which highlights the need for future research to investigate psychotic and bipolar disorders separately and also to examine both psychotic and manic symptoms.

There are many features of the study design that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, causality cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional research design. Any findings suggesting psychedelic use elicits unusual visual experiences or psychotic symptoms could also be interpreted to mean that unusual visual experiences or psychotic symptoms elicit psychedelic use. Consistent with this interpretation, family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders (i.e., a variable that could not be affected by lifetime psychedelic use) was more commonly reported among those who reported lifetime use of psychedelics. Second, even though the sample was stratified across sex, age, and ethnicity to reflect the demographic distribution of the US adult population, it may not have been representative on other relevant variables such as income or educational attainment. It is also possible that associations in the covariate-adjusted models were influenced by other variables not included in the survey that are relevant to unusual visual experiences and psychotic symptoms (e.g., amphetamine use). Fourth, the survey item related to HPPD did not specify whether it concerned HPPD type I or II. Given that the estimated prevalence rate of HPPD type II among hallucinogen users is extremely low (Halpern et al. 2016), it is possible that those respondents who reported HPPD diagnosis by a doctor or other medical professional had received a HPPD type I diagnosis. It should be noted, however, that these may have been inaccurate diagnoses. For example, it is possible that distressing symptoms associated with psychedelic use were labeled HPPD as a diagnostic category necessary for third party reimbursement. Fifth, the questionnaires in this study used the same phrases that were used in the original questionnaires, which resulted in different time frames for unusual visual experiences (at any point across the lifetime) and psychotic symptoms (past 2 weeks). This suggests that the reported associations of psychedelic use with unusual visual experiences and psychotic symptoms may not be comparable. Sixth, respondents were asked whether they had a current or past history of a psychotic or bipolar disorder and also whether they had a first- or second-degree relative with a psychotic or bipolar disorder, which corresponds with criteria that would typically lead to exclusion from participation in a clinical trial with psychedelics. The respondents were not, however, asked to specify whether they had either a personal or family history of either psychotic disorders or bipolar disorders per se (or subtypes thereof), which would have been useful in determining the associations of each unique disorder. Future research should use longitudinal research designs to investigate interaction effects between psychedelic use and potentially relevant psychiatric histories (e.g., anxiety disorders) on unusual visual experiences. It would also be important to investigate interaction effects between psychedelic use and more specific psychiatric histories (e.g., schizophrenia, brief psychotic disorder, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder) on psychotic and manic symptoms.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of this study, the current results suggest that lifetime naturalistic use of psychedelics might be associated with more unusual visual experiences across the lifetime, as well as more psychotic symptoms in the past 2 weeks for individuals with a family history of psychotic or bipolar disorders and the reverse for those without such a family history. Future research should distinguish between different psychotic and bipolar disorders and specify subtypes of these mental health conditions and should also utilize other research designs (e.g., longitudinal) and variables (e.g., polygenic risk scores) to better understand potential cause-and-effect relationships.

Data Availability

The data and Stata syntax are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24316432.v1.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental diseases (DSM-V), 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association Press, Washington, DC

Andersen KA, Carhart-Harris R, Nutt DJ, Erritzoe D (2021) Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: a systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 143(2):101–118

Baggott MJ, Coyle JR, Erowid E, Erowid F, Robertson LC (2011) Abnormal visual experiences in individuals with histories of hallucinogen use: a web-based questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend 114(1):61–67

Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R et al (2021) Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med 384(15):1402–1411

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160

Galvão-Coelho NL, Marx W, Gonzalez M, Sinclair J, de Manincor M, Perkins D, Sarris J (2021) Classic serotonergic psychedelics for mood and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of mood disorder patients and healthy participants. Psychopharmacology 238(2):341–354

Gard DE, Pleet MM, Bradley ER, Penn AD, Gallenstein ML, Riley LS et al (2021) Evaluating the risk of psilocybin for the treatment of bipolar depression: a review of the research literature and published case studies. J Affect Disord Rep 6:100240

Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC et al (2022) Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med 387(18):1637–1648

Halpern JH, Lerner AG, Passie T (2016) A Review of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) and an Exploratory Study of Subjects Claiming Symptoms of HPPD. In: Halberstadt AL, Vollenweider FX, Nichols DE (eds) Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, vol 36. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2016_457

Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr (2003) Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years? Drug Alcohol Depend 69(2):109–119

Johnson MW, Richards WA, Griffiths RR (2008) Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol 22(6):603–620

Krebs TS, Johansen PØ (2013) Psychedelics and mental health: a population study. PLoS One 8(8):e63972

Kuzenko N, Sareen J, Beesdo-Baum K, Perkonigg A, Höfler M, Simm J et al (2011) Associations between use of cocaine, amphetamines, or psychedelics and psychotic symptoms in a community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 123(6):466–474

Lebedev AV, Acar K, Garzón B, Almeida R, Råback J, Åberg A et al (2021) Psychedelic drug use and schizotypy in young adults. Sci Rep 11(1):15058

Müller F, Kraus E, Holze F, Becker A, Ley L, Schmid Y et al (2022) Flashback phenomena after administration of LSD and psilocybin in controlled studies with healthy participants. Psychopharmacology 239(6):1933–1943

Roscoe J, Lozy O (2022) Can psilocybin be safely administered under medical supervision? A systematic review of adverse event reporting in clinical trials. Drug Sci Policy Law 8:20503245221085222

Ruderfer DM, Ripke S, McQuillin A, Boocock J, Stahl EA, Pavlides JMW et al (2018) Genomic dissection of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, including 28 subphenotypes. Cell 173(7):1705–1715

Schlag AK, Aday J, Salam I, Neill JC, Nutt DJ (2022) Adverse effects of psychedelics: from anecdotes and misinformation to systematic science. J Psychopharmacol 36(3):258–272

Simonsson O, Sexton JD, Hendricks PS (2021) Associations between lifetime classic psychedelic use and markers of physical health. J Psychopharmacol 35(4):447–452

Strassman RJ (1984) Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis 172(10):577–595

von Rotz R, Schindowski EM, Jungwirth J, Schuldt A, Rieser NM, Zahoranszky K et al (2023) Single-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy in major depressive disorder: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 56(101809)

Zimmerman M, Mattia JI (2001) A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58(8):787–794

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. OS was supported by Osmond Foundation, Ekhaga Foundation and Olle Engkvist Foundation. SG was supported by a grant (K23AT010879) from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Support for this research was also provided by FORMAS, Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (Grant number: FR-2018/0006), Three Springs Foundation through the Monash Centre for Consciousness & Contemplative Studies, the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, and the University of Wisconsin - Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and with funding from the Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OS conceptualized and designed the study, with input from SG and PSH. OS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All drafts received comments and input from SG, PSH, RC, and WO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was deemed to be exempt by the Internal Review Board (IRB) at UW-Madison.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Conflict of interest

PSH has been in paid advisory relationships with the following organizations regarding the development of psychedelics and related compounds: Bright Minds Biosciences Ltd., Eleusis Benefit Corporation, Journey Colab Corporation, Reset Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Silo Pharma. OS and RC were co-founders of Eudelics AB.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article belongs to a Special Issue on Psychedelics 2024

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 107 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simonsson, O., Goldberg, S., Chambers, R. et al. Psychedelic use and psychiatric risks. Psychopharmacology (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-023-06478-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-023-06478-5