Abstract

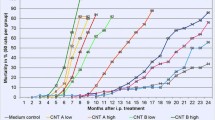

Potassium octatitanate (K2O·8TiO2, POT) fibers are used as an alternative to asbestos. Their shape and biopersistence suggest that they are possibly carcinogenic. However, inhalation studies have shown that respired POT fibers have little carcinogenic potential. We conducted a short-term study in which we administered POT fibers, and anatase and rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles (a-nTiO2, r-nTiO2) to rats using intra-tracheal intra-pulmonary spraying (TIPS). We found that similarly to other materials, POT fibers were more toxic than non-fibrous nanoparticles of the same chemical composition, indicating that the titanium dioxide composition of POT fibers does not appear to account for their lack of carcinogenicity. The present report describes the results of the 3-week and 52-week interim killing of our current 2-year study of POT fibers, with MWCNT-7 as a positive control and r-nTiO2 as a non-fibrous titanium dioxide control. Male F344 rats were administered 0.5 ml vehicle, 62.5 µg/ml and 125 µg/ml r-nTiO2 and POT fibers, and 125 µg/ml MWCNT-7 by TIPS every other day for 2 weeks (eight doses: total doses of 0.25 and 0.50 mg/rat). At 1 year, POT and MWCNT-7 fibers induced significant increases in alveolar macrophage number, granulation tissue in the lung, bronchiolo-alveolar cell hyperplasia and thickening of the alveolar wall, and pulmonary 8-OHdG levels. The 0.5 mg POT- and the MWCNT-7-treated groups also had increased visceral and parietal pleura thickness, increased mesothelial cell PCNA labeling indices, and a few areas of visceral mesothelial cell hyperplasia. In contrast, in the r-nTiO2-treated groups, none of the measured parameters were different from the controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potassium octatitanate fibers (POT fibers: K2O·8TiO2) are heat resistant and have high tensile strength and chemical stability, giving them numerous commercial uses. However, in combination with their straight, needle-like shape, these properties also make POT fibers highly biopersistent in living tissues. Notably, POT fibers have been recovered from the rat lung 12 months after inhalation exposure without any erosion (Yamato et al. 2002). The fiber pathogenicity paradigm identifies biopersistent fibers with aerodynamic diameters that allow them to be deposited beyond the ciliated airways as potential lung carcinogens (Donaldson et al. 2011). Application of POT fibers directly to the pleural surface of Osborne–Mendel rats and administration of POT fibers to female F344 rats by intraperitoneal injection resulted in induction of malignant tumors (Adachi et al. 2001; Stanton and Layard 1978; Stanton et al. 1981), demonstrating that POT fibers are carcinogenic when in contact with susceptible tissues, and in 2006 the WHO Workshop on Mechanisms of Fibre Carcinogenesis and Assessment of Chrysotile Asbestos Substitutes issued a statement that “respirable potassium octatitanate fibers are likely to pose a high hazard to humans after inhalation exposure” (WHO 2005). However, long-term inhalation studies have reported mostly negative results (Ikegami et al. 2004; Lee et al. 1981; Oyabu et al. 2004; Yamato et al. 2003). (See Supplementary Doc S1 for a brief overview of in vivo POT fiber studies.)

Thus, the physical characteristics of POT fibers and the fact that they can induce malignant transformation in susceptible tissues suggest high carcinogenic potential, but inhalation studies indicate that respirable POT fibers have low carcinogenic potential in test animals. To investigate the possibility that this apparent discrepancy was due to the titanium dioxide composition of POT fibers, we conducted a short-term experiment to compare the toxicity of POT fibers with two titanium dioxide nanoparticles, anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles (a-nTiO2) and rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles (r-nTiO2). We administered POT fibers and a-nTiO2 and r-nTiO2 to the lungs of rats using intra-tracheal intra-pulmonary spraying (TIPS) and found that POT fibers had greater biopersistence and induced a greater degree of toxicity in the lung than a-nTiO2 or r-nTiO2 (Abdelgied et al. 2018). These results are in agreement with the findings of studies with other materials that fiber-shaped materials are more toxic to the lungs than spherical-shaped nanoparticles of the same chemical composition (Braakhuis et al. 2014). Thus, the titanium dioxide composition of POT fibers does not appear to explain their lack of carcinogenicity in the lung. Therefore, we are conducting a 2-year study comparing the lung toxicity of POT fibers to r-nTiO2 and MWCNT-7, a known lung carcinogen in rats (Kasai et al. 2016). This report describes the results of the interim killing made 1 week and 1 year after the final TIPS administration of the test materials. Overall, we found that at 1 year POT fibers had a similar or greater degree of toxicity in the lung and pleural cavity compared to MWCNT-7.

Materials and methods

Preparation of particle suspension

All three particles were dispersed by the Taquann method to generate aerosols consisting predominantly of dispersed single fibers/particles (Taquahashi et al. 2013). After dispersion, the material was stored in tert-butyl alcohol. Shortly before administration, the frozen T-butyl alcohol was removed using an Eyela Freeze Drying machine (FDU-2110; Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The test materials were then dispersed in saline containing 0.5% poloxamer-188 solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at concentrations of 62.5 and 125 µg/ml (POT and r-nTiO2) and 125 µg/ ml (MWCNT 7), and then sonicated for 30 min using an SFX250 bench top sonicator at 250 watts and a frequency of 20 kHz. (Sonifier®, Emerson Electric Asia-Pacific, Hong Kong). To minimize aggregation, after transfer to the animal rooms the suspensions were kept in a Bransonic M1800-J bath sonicator (Branson Ultrasonics Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Characterization of particles in suspension

After sonication, 20 µl of each test material suspension was placed on a micro-grid membrane pasting copper mesh (EMS 200-Cu, Nisshin EM Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The shape of the nanoparticles was imaged by transmission electron microscopy (JEOL Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and the photos were analyzed by NIH image analyzer software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Over 1000 particles of each type of material were measured.

Animals

Nine-week-old male F344 rats were purchased from Charles River Japan Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan). The rats were housed in the animal center of Nagoya City University Medical School, maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle, and received oriental MF basal diet (Oriental Yeast Co., Tokyo, Japan) and water ad libitum. The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagoya City University Medical School. The research was conducted according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Nagoya City University.

Experimental design

After acclimatization for 2 weeks, 210 rats were divided into seven groups of 30 animals each: group 1, without treatment; group 2, vehicle (saline plus 0.5% poloxamer-188 solution); group 3, administered 0.25 mg r-nTiO2; group 4, administered 0.5 mg r-nTiO2; Group 5, administered 0.25 mg POT fibers; Group 6, administered 0.50 mg POT fibers; and Group 7, administered 0.50 mg MWCNT-7. Vehicle and test material suspensions were administered to the animals by intra-tracheal intra-pulmonary spraying (TIPS) using a microsprayer (series IA–1B Intratracheal Aerosolizer Penn-century, Philadelphia, PA) under 3% isoflurane anesthesia as previously described (Xu et al. 2012). Rats were administered 0.5 ml vehicle, 62.5 µg/ml and 125 µg/ml r-nTiO2 and POT fibers, and 125 µg/ml MWCNT-7 once every other day over a 15-day period (eight doses). Three weeks and 52 weeks after the start of the experiment interim killing was performed: five rats from each group were killed by exsanguination from the abdominal aorta under deep isoflurane anesthesia.

The high dose of 0.50 mg resulted in a lung burden of approximately 0.5 mg particles per gram lung tissue when instilled into the lungs of 11-week-old male F344 rats (see Table S5 in Supplementary Doc S2). This dose was chosen based in part on the results of studies with poorly soluble materials, including POT fibers, in which lung burdens above approximately 1–3 mg inhaled particles per gram lung tissue altered retention kinetics in the lung (Elder et al. 2005; Oyabu et al. 2004). The high dose is also equal to one-half of the amount of MWCNT-N, which is similar to MWCNT-7, that was found to be carcinogenic in an earlier study using TIPS administration (Suzui et al. 2016).

At 1 week after the final TIPS administration, one of the measured parameters (macrophage counts) was elevated in the vehicle control group compared to the untreated group (Table S6 in Supplementary Doc S3). Therefore, only data obtained at the 1-year interim sacrifice were used to assess the toxicity of the test materials. All of the data obtained from the 3-week sacrifice are shown in Supplementary Doc S2 and Tables S6, S7, and S9 in Supplementary Doc S3.

Tissue sample collection, organ weights, and pathological examination

The animals were observed daily for clinical signs and mortality. Body weights were measured weekly throughout the experimental period. At necropsy, blood samples were collected via the abdominal aorta under deep isoflurane anesthesia and serum samples were stored at − 80 °C. Organs, including lung, liver, kidney, spleen, brain, and testes, were weighed and examined for any macroscopic lesions. The lungs were excised and the right upper and middle lobes were cut into pieces and immediately frozen at − 80 °C for biochemical analysis. The remaining right lobes and the left lung were inflated and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) adjusted to pH 7.3 and processed for immunohistochemical, light microscopic, and electron microscopic examinations. Collagen deposition in the lung tissue, and the visceral and parietal pleura was quantified in light microscopic images of lung tissue sections stained with Masson’s trichrome (Abcam, Tokyo, Japan) using NIH image analyzer software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA): ten individual images were captured from each of three longitudinal lung sections from each rat. The trachea, heart, lymph nodes (including mediastinal lymph nodes), epididymis, seminal vesicles, prostrate, intestines, spinal bone, muscles, and diaphragm were processed and examined histopathologically.

Polarized light microscopy and electron microscopy

Identification of the dosed materials in the tissue cells and alveolar macrophages was made by polarized microscopy (PLM, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For high-magnification viewing, slides were immersed in xylene to remove the cover glass, immersed in 100% ethanol, then air-dried and coated with platinum, and viewed by SEM (Field Emission Scanning Electronic Microscope; Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) at 5–10 kV. For ultrafine viewing of the dosed materials in the lung, the area in the paraffin block corresponding to the H&E slide was cut out, deparaffinized, and embedded in epoxy resin and processed for TEM (EDAX, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

For CD68, PCNA, 8-OHDG, and mesothelin/ERC staining, lung sections processed for immunohistochemical analysis were used. Sections were incubated with anti-rat-CD68 (T-3003; BMA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), anti-PCNA (D3H8P; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-8-OHdG (15A3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and anti-rat mesothelin/c-ERC (28,001; Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd.) diluted 1:2000 in PBS containing 1% BSA and 1% goat serum overnight at 4 °C, then incubated with secondary antibody (414191F; Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan), visualized with DAB (Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan), and counterstained with hematoxylin. In sections stained with CD68, the number of alveolar macrophages (CD68-positive cells) were counted and expressed as number per cm2. In sections stained with PCNA, more than 1000 pulmonary epithelial cells and more than 500 pleural mesothelial cells were counted blindly in random fields. All nuclei showing staining of more than half of the nucleus were considered to be positive.

Collection of the pleural lavage fluid (PLF) and the pleural lavage cell pellet

Collection of the PLF and preparation of the pleural lavage cell pellet were performed as previously described (Abdelgied et al. 2018).

Measurement of lactate dehydrogenase and total protein in the PLF

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured using an LDH activity assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and total protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein assay kit (Pierce biotech, Rockford, IL, USA).

Biochemical analysis of the lung tissue

Total oxidant status (TOS) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) levels were measured using total antioxidant status and total oxidant status kits (Rel Assay diagnostics, Gaziantep, Turkey). Oxidative stress index (OSI) was calculated as OSI = TOS/TAC.

The OxiSelect® TBARS Assay Kit (STA-330, Cell Biolabs) was used to measure thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in lung tissue.

For quantification of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in lung tissue DNA, lung tissue samples (approximately 50 mg) were washed in ice-cold PBS and total DNA was extracted using “FitAmp™ General Tissue Section DNA Isolation Kit” (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY, USA). The concentration of DNA was measured using a Nanodrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, USA). The level of 8-OHdG was measured using an EpiQuikTM 8-OHdG DNA Damage Quantification Direct Kit (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY, USA).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was isolated as previously described (Abdelgied et al. 2018). The RNA integrity numbers of all samples were higher than 8. 1 µg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) using the SuperScript TM III system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Real-time PCR was performed with Power up™ SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) in MicroAmp Optical 96-well Reaction Plates (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System. The cycling parameters were 2 min at 50 °C and 2 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 55 °C and 60 s at 72 °C. Each reaction in the 96-well plates was performed in triplicates and results from three independent 96-well plates were used for analysis. Target genes were normalized to actin using the 2 (−∆∆CT) method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001) with actin and target gene reactions performed in the same 96-well plates. Primers were designed using Primer Premier 6.11 software (Premier Biosoft International, CA, USA) and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Primers are listed in Table S8 in Supplementary Doc S3.

ELISA for CCL2 and CCL3

Samples were prepared as previously described (Abdelgied et al. 2018). The levels of CCL2 and CCL3 in the tissue supernatants were measured using Rat MCP-1 and CCL3 Picokine™ ELISA Kits (Boster Biological Technology, Pleasanton, CA), and the values expressed as pg/mg lung tissue.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed for homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test when the variance was homogenous or the Games–Howell post hoc test when the variance was not homogeneous. SPSS software version 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Characterization of test materials dispersed in working solutions

POT fibers, MWCNT-7 fibers, and r-nTiO2 particles were supplied by Dr. A. Hirose (one of the authors). The primary sizes of the POT fibers and r-nTiO2 particles are described in Abdelgied et al. (2018). The primary sizes of the MWCNT-7 fibers were 5.305 ± 3.81 µm in length and 75.65 ± 20.54 nm in width. The dimensions of all three test materials were evenly distributed around their means (data not shown). Fig. S2 in Supplementary Doc S4 shows transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images of the three test materials.

Pathological findings

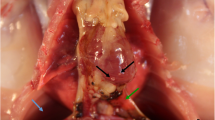

Body and organ weights are described in Supplementary Doc S2. The lungs of the MWCNT-7 treated rats were dark grayish in color at both weeks 3 and 52, while the r-nTiO2- and POT-treated rats showed normal external lung morphology. At week 52, the lungs of vehicle- and r-nTiO2 (0.25 and 0.5 mg)-treated rats showed normal lung histology (Fig. 1a, b); however, the lungs of the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated rats showed reactive bronchiolo-alveolar cell hyperplasia, thickening of the alveolar wall, and granulation tissue encasing the administered materials (Fig. 1c–f). Fibrotic changes with increased deposition of collagen in the alveolar wall, the areas around the bronchioles, in granulation tissue (Fig. 2), and in the sub-pleural tissues of the visceral and parietal pleura (Fig. 3) were observed in the 0.50 mg POT- and MWCNT-7-treated rats: Pulmonary collagen and the thickness of the visceral and parietal pleura are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Hyperplasia of the visceral mesothelium was found in two rats in the 0.50 mg POT group and in one rat in the 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated group (Fig. 4): Hyperplasia of mesothelial cells was confirmed by staining for mesothelin (Fig. 4).

Histological observation of lung tissue at week 52 of rats administered; a, b 0.50 mg r-nTiO2, c, d 0.50 mg POT fibers, and e, f 0.50 mg MWCNT-7. The lung histology of the untreated and vehicle control rats, and the rats administered 0.25 mg r-nTiO2-treated rats was similar to that of the rats administered 0.50 mg r-nTiO2 shown in a and b. The lung histology of rats administered 0.25 mg POT fibers was similar to, but less intense than, that of the rats administered 0.50 mg POT fibers shown in c and d. Black arrows indicate alveolar macrophages phagocytizing test materials. White arrows indicate granulation tissue. Striped arrows indicate thickening and hyperplasia of the alveolar epithelium. Inserts: polarized light microscope images

Three lung sections from each rat in the POT and MWCNT-7 groups were examined for granulation tissue. The average number of granulation tissue lesions found in the 0.50 mg POT-treated rats was 5.20 ± 2.28, which was significantly lower than the average number found in the MWCNT-7-treated rats, 56.40 ± 12.20, p < 0.001.

Numerous POT and MWCNT-7 fibers persisted in the lung at week 52. These fibers were mostly internalized in granulation tissue and the alveolar wall (Fig. 1c–f), but a considerable number of POT fibers were found free or partially engulfed by macrophages in the alveolar space (Fig. 1d). Macrophages were also found interacting with MWCNT-7 fibers (Fig. 1f).

At week 52, the number of alveolar macrophages in the r-nTiO2- and 0.25 mg POT-treated rats was the same as in the controls; however, the number of alveolar macrophages was significantly elevated in the 0.50 mg POT- and MWCNT-7-treated rats (Table 1). The number of macrophages phagocytosing test materials in the 0.25 mg and 0.50 mg r-nTiO2-treated rats and the 0.25 mg POT-treated rats at week 52 was considerably reduced from week 3 (see Macrophages with test particles shown in Supplementary Table S6 and Table 1), suggesting that free particles were mostly cleared from the lungs of these rats. The percentage of macrophages phagocytosing test materials remained relatively high in the 0.50 mg POT- and MWCNT-7-treated rats (Table 1). r-nTiO2 was completely engulfed by macrophages without causing any obvious cellular distortions (Fig. 5a, d). In contrast, both POT and MWCNT-7 fibers can be seen penetrating alveolar macrophages (Fig. 5b, c), indicative of frustrated phagocytosis. These cells also have vacuolated cytoplasm (Fig. 5e, f), a morphology seen in macrophages undergoing autophagy due to oxidative stress (Perrotta et al. 2011).

SEM and TEM of alveolar macrophages from rats treated with 0.50 mg r-nTiO2, POT fibers, and MWCNT-7 fibers. a–c SEM images of macrophages. Striped arrows designate macrophages. White arrows indicate POT b and MWCNT-7 c fibers. d–f TEM images of alveolar macrophages engulfing the three test materials (white arrows). White arrows indicate r-nTiO2 (d), POT fibers (e), and an MWCNT-7 fiber (f). Black arrows indicate cytoplasmic vacuoles. The hatched arrow indicates a phagosomal membrane in a macrophage phagocytizing POT fibers; POT fibers can only be seen in cross section in TEM images because the thickness of the ultra-thin tissue sections used for TEM (less than 100 nm) is less than the thickness of POT fibers (300 nm)

Small amounts of all three test materials were detected in extrapulmonary organs, including the heart, epididymis, liver, kidney, and spleen at both week 3 and week 52 (Fig. S3 in Supplementary Doc S4), but without causing obvious inflammation or other pathological changes.

Several POT fibers, but only a very few, mostly long, MWCNT-7 fibers were detected in the pleural cavity lavage cell pellet (Fig. S4 in Supplementary Doc S4). Most of these fibers appeared to be free. In contrast, no r-nTiO2 particles were detected in the pleural cavity lavage cell pellet. POT and MWCNT-7 fibers were also found in the mediastinal lymph nodes, with the number of fibers that had translocated to the mediastinal lymph nodes obviously higher in the 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated rats compared to the 0.50 mg POT-treated rats (Fig. S5 in Supplementary Doc S4).

Total protein (TP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the pleural cavity lavage fluid

At week 52, TP in the pleural cavity lavage fluid (used as an indicator of tissue integrity) was elevated in the 0.50 mg POT-treated group (Table 2). Notably, TP in the POT (0.5 mg/ rat)-treated group was also significantly higher than in the MWCNT-7 treated group. LDH activity in the pleural cavity lavage fluid, an indicator of cellular toxicity, was not different in any of the treated groups compared to the controls (data not shown).

Oxidative stress parameters in the lung

At week 52, pulmonary TOS, TAC, OSI, and TBARS levels did not show any significant changes in the treated rats compared to the controls (data not shown).

Pulmonary 8-OHdG levels

At week 52, pulmonary 8-OHdG levels were significantly increased in the 0.50 mg POT-treated rats (Table 1, Fig. S6 in Supplementary Doc S4). 8-OHdG levels were also elevated in the rats treated with MWCNT-7, but without statistical significance. There was no significant difference between the POT- and MWCNT-7-treated groups. 8-OHdG levels were not elevated in the rats treated with r-nTiO2.

Pulmonary and mesothelial cell proliferation

At week 52, there was a significant increase in the PCNA labeling indexes of lung alveolar epithelium in the 0.25 mg POT-, 0.50 mg POT-, and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated groups (Table 1, Fig. S7 in Supplementary Doc S4). There was no significant difference between the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated groups. The PCNA labeling index of visceral mesothelium was also significantly increased in the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated groups (Table 1, Fig. S8 in Supplementary Doc S4). There was no significant difference between the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated groups. Similarly, the PCNA labeling index of the parietal mesothelium was significantly increased in the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated groups (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S8). Again, there was no significant difference between the POT- and MWCNT-7-treated groups. PCNA labeling indexes were not elevated in the lung or pleura in r-nTiO2-treated rats.

Pulmonary expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

At week 52, we found increases in the CCL2 RNA expression in the lung tissue of 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated rats compared to the vehicle controls, and increased CCL3 RNA expression in the lung tissue of 0.50 mg POT-treated rats (Table S9 in Supplementary Doc S3). There was no significant difference in the expression of CCL4 between any of the treated groups and the vehicle control group. Therefore, we measured the protein concentration of CCL2 and CCL3 in lung tissue homogenates. We found slight but significant increases in CCL2 and CCL3 levels in the 0.50 mg POT- and 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated rats compared to the controls (Table 1).

Discussion

This report describes the results of interim killing of a 2-year study that were performed at 1 week and 1 year after TIPS administration of POT fibers, r-nTiO2, and MWCNT-7, a known carcinogen in the rat lung (Kasai et al. 2016). At 1 year in rats administered POT fibers and MWCNT-7, there were persistent inflammatory and fibrotic changes in the lung and pleura, elevated alveolar macrophage counts, elevated levels of CCL2 and CCL3 in the lung tissue, increased levels of 8-OHdG adducts in the lung tissue DNA, and increased PCNA labeling of lung alveolar cells and visceral and parietal mesothelium. Hyperplasia of the visceral mesothelium was found in two of five rats in the 0.50 mg POT group and one of five rats in the 0.50 mg MWCNT-7 group. In contrast, none of these parameters was elevated in rats administered r-nTiO2.

Inhaled fibers and dusts that are deposited beyond the ciliated airways are subject to various lung defenses. The first of these consists of alveolar macrophages, which will attempt to phagocytose and destroy the invading particle by generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The interaction with foreign particles will also result in macrophages releasing mediators that attract neutrophils. The neutrophils will attempt to eliminate the invading particle by a range of mechanisms including the release of oxygen radicals and cytotoxic peptides and proteins. The tissue damage consequent to the release of cytotoxic agents by macrophages and neutrophils will result in a tissue repair response. Importantly, if the particle is not degraded or physically removed, the macrophage/neutrophil response to the particle will continue during the tissue repair process, exposing the DNA of dividing cells to DNA damaging agents and greatly increasing the probability of DNA mutations being fixed in the genomes of daughter cells (also see Supplementary Material 1 in (El-Gazzar et al. 2018). Particles that exceed the phagocytic capacity of macrophages (see Fig. 5) are not easily removed physically, and these fibers may be sequestered in granulation tissue (see Fig. 1). However, if the fibers remain free (see Fig. 1) they can provoke repeated cycles of tissue damage and repair that may result in some cells acquiring the mutations necessary for initiating the neo-transformation process.

In the present study, increased numbers of alveolar macrophages were still present in the lungs of POT- and MWCNT-7-treated rats 1 year after TIPS administration (see Table 1), and a significant fraction of these macrophages was engulfing, or attempting to engulf, POT and MWCNT fibers (see Fig. 1; Table 1). Inflammatory changes, production of 8-OHdG adducts, and increased PCNA indexes in the lung were evident in these animals (see Figs. 1, 2; Table 1; and Supplementary Fig. S6, S7).

Particles inhaled into the lung can translocate into the lymphatic system and hence into the pleural cavity (Harmsen et al. 1985; Miserocchi et al. 2008; NIOSH 2011). As in the lung, biopersistent particles retained in the pleural cavity can interact with pleural tissues and macrophages, and provoke repeated cycles of damage and repair and consequent fixation of DNA mutations into the genomes of mesothelial cells. In the present study, free POT and MWCNT-7 fibers were found in the pleural cavity lavage cell pellet, and collagen deposition at the visceral and parietal pleura, indicative of damage to the pleura, was also evident in these rats (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, total protein concentration in the pleural cavity lavage fluid, an indicator of tissue integrity, was elevated in POT-treated rats (see Table 2). Finally, the PCNA indexes of both the visceral and parietal mesothelium were elevated in POT- and MWCNT-7-treated rats (see Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S8), and importantly, two of the five rats in the 0.50 mg POT-treated group and one of the five rats in the 0.50 mg MWCNT-7-treated group had hyperplastic lesions in the visceral mesothelium (see Fig. 4).

Cytokine analysis of the lung tissue showed that both POT fibers and MWCNT-7 induced elevation of CCL2 and CCL3 levels in the lung tissue. These cytokines are potent chemotaxins and their expression can lead to the recruitment of monocytes, macrophages, monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and this process is associated with tumor development (Deshmane et al. 2009; Huang et al. 2007; Kitamura et al. 2015; Salcedo et al. 2000; Solinas et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2008; Yoshimura 2017).

In summary, there is clear evidence that POT fibers are toxic in the lung and pleura of male rats. POT fibers were biopersistent in the lung and mesothelium of rats, provoking inflammation and tissue and DNA damage. These results are in agreement with the physical characteristics of these fibers and the potential adverse health effects of thin, long, biopersistent fibers. The pulmonary and pleural toxicity of POT fibers was similar or greater than that of MWCNT-7, a known carcinogen to the rat lung.

References

Abdelgied M, El-Gazzar AM, Alexander DB et al (2018) Potassium octatitanate fibers induce persistent lung and pleural injury and are possibly carcinogenic in male Fischer 344 rats. Cancer Sci 109(7):2164–2177. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13643

Adachi S, Kawamura K, Takemoto K (2001) A trial on the quantitative risk assessment of man-made mineral fibers by the rat intraperitoneal administration assay using the JFM standard fibrous samples. Industrial Health 39(2):168–174

Braakhuis HM, Park MV, Gosens I, De Jong WH, Cassee FR (2014) Physicochemical characteristics of nanomaterials that affect pulmonary inflammation. Part Fibre Toxicol 11:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-11-18

Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE (2009) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res 29(6):313–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/jir.2008.0027

Donaldson K, Murphy F, Schinwald A, Duffin R, Poland CA (2011) Identifying the pulmonary hazard of high aspect ratio nanoparticles to enable their safety-by-design. Nanomedicine (Lond) 6(1):143–156. https://doi.org/10.2217/nnm.10.139

Elder A, Gelein R, Finkelstein JN, Driscoll KE, Harkema J, Oberdorster G (2005) Effects of subchronically inhaled carbon black in three species. I. Retention kinetics, lung inflammation, and histopathology. Toxicol Sci 88(2):614–629. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfi327

El-Gazzar AM, Abdelgied M, Alexander DB et al (2018) Comparative pulmonary toxicity of a DWCNT and MWCNT-7 in rats. Arch Toxicol 5:1–11

Harmsen AG, Muggenburg BA, Snipes MB, Bice DE (1985) The role of macrophages in particle translocation from lungs to lymph nodes. Science 230(4731):1277–1280

Huang B, Lei Z, Zhao J et al (2007) CCL2/CCR2 pathway mediates recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells to cancers. Cancer Lett 252(1):86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.012

Ikegami T, Tanaka A, Taniguchi M et al (2004) Chronic inhalation toxicity and carcinogenicity study on potassium octatitanate fibers (TISMO) in rats. Inhal Toxicol 16(5):291–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958370490428391

Kasai T, Umeda Y, Ohnishi M et al (2016) Lung carcinogenicity of inhaled multi-walled carbon nanotube in rats. Part Fibre Toxicol 13(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-016-0164-2

Kitamura T, Qian BZ, Soong D et al (2015) CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med 212(7):1043–1059. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20141836

Lee KP, Barras CE, Griffith FD, Waritz RS (1981) Pulmonary response and transmigration of inorganic fibers by inhalation exposure. Am J Pathol 102(3):314–323

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25(4):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Miserocchi G, Sancini G, Mantegazza F, Chiappino G (2008) Translocation pathways for inhaled asbestos fibers. Environ Health 7:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-7-4

NIOSH (2011) Current intelligence bulletin 62. Asbestos fibers and other elongate mineral particles: state of the science and road map for research. 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2011-159/pdfs/2011-159.pdf Accessed 24 Oct 2017

Oyabu T, Yamato H, Ogami A et al (2004) The effect of lung burden on biopersistence and pulmonary effects in rats exposed to potassium octatitanate whiskers by inhalation. J Occup Health 46(5):382–390

Perrotta I, Carito V, Russo E, Tripepi S, Aquila S, Donato G (2011) Macrophage autophagy and oxidative stress: an ultrastructural and immunoelectron microscopical study. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2011:282739. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/282739

Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA et al (2000) Human endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: direct role of MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood 96(1):34–40

Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P (2009) Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 86(5):1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0609385

Stanton MF, Layard M (1978) The carcinogenicity of fibrous minerals. In: workshop on asbestos: definitions and measurement methods. National Bureau of Standards Special Publication. https://ia801405.us.archive.org/6/items/proceedingsofwor506grav/proceedingsofwor506grav.pdf Accessed 08 Dec 2018. 506:143–151

Stanton MF, Layard M, Tegeris A et al (1981) Relation of particle dimension to carcinogenicity in amphibole asbestoses and other fibrous minerals. J Natl Cancer Inst 67(5):965–975

Suzui M, Futakuchi M, Fukamachi K et al (2016) Multiwalled carbon nanotubes intratracheally instilled into the rat lung induce development of pleural malignant mesothelioma and lung tumors. Cancer Sci 107(7):924–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12954

Taquahashi Y, Ogawa Y, Takagi A, Tsuji M, Morita K, Kanno J (2013) Improved dispersion method of multi-wall carbon nanotube for inhalation toxicity studies of experimental animals. J Toxicol Sci 38(4):619–628

WHO (2005) Workshop on Mechanisms of fibre carcinogenesis and assessment of chrysotile asbestos substitutes 8–12 November 2005, Lyon, France. Summary Consensus Report. https://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/new_issues/summary_report.pdf Accessed 22 Oct 2018

Wu Y, Li YY, Matsushima K, Baba T, Mukaida N (2008) CCL3-CCR5 axis regulates intratumoral accumulation of leukocytes and fibroblasts and promotes angiogenesis in murine lung metastasis process. J Immunol 181(9):6384–6393

Xu J, Futakuchi M, Shimizu H et al (2012) Multi-walled carbon nanotubes translocate into the pleural cavity and induce visceral mesothelial proliferation in rats. Cancer Sci 103(12):2045–2050. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12005

Yamato H, Morimoto Y, Tsuda T et al (2002) Clearance of inhaled potassium octatitanate whisker from rat lungs. J Occupat Health 44(1):34–39

Yamato H, Oyabu T, Ogami A et al (2003) Pulmonary effects and clearance after long-term inhalation of potassium octatitanate whiskers in rats. Inhal Toxicol 15(14):1421–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958370390248969

Yoshimura T (2017) The production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCL2 in tumor microenvironments. Cytokine 98:71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2017.02.001

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan (Grant number: 'H30-kagaku-shitei-004', ‘H27-kagaku-shitei-004’, ‘H25-kagaku-ippan-004’, 'H28-kagaku-ippan 004'); YOG Specified Nonprofit Corporation; Association for the Promotion of Research on Risk Assessment; and the Egyptian cultural affairs and missions sector. The authors wish to thank Chisato Ukai for administrative assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Horiyuki Tsuda received 3,000,000 JPY from YOG Specified Nonprofit Corporation. There are no other potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelgied, M., El-Gazzar, A.M., Alexander, D.B. et al. Pulmonary and pleural toxicity of potassium octatitanate fibers, rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles, and MWCNT-7 in male Fischer 344 rats. Arch Toxicol 93, 909–920 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-019-02410-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-019-02410-z