Abstract

Summary

Aging alone is not the only factor accounting for poor bone health in older men. There are modifiable factors and lifestyle choices that may influence bone health and result in higher bone density and lower fracture risk even in very old men.

Introduction

The aim of this cross-sectional analysis was to identify the factors associated with areal bone mineral density (BMD) and their relative contribution in older men.

Methods

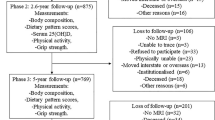

The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project is a population-based study in Sydney, Australia, involving 1,705 men aged 70–97. Data were collected using questionnaires and clinical assessments. BMD of the hip and spine was measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry.

Results

In multivariate regression models, BMD of the hip was associated with body weight and bone loading physical activities, but not independently with age. The positive relationship between higher BMD and recreational activities is attenuated with age. Factors independently associated with lower BMD at the hip were inability to stand from sitting, a history of kidney stones, thyroxine use, and Asian birth and at the spine, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, paternal fracture history, and thyroxine use. Higher body weight, participation in dancing, tennis or jogging, quadriceps strength, alcohol consumption, and statin use were associated with higher hip BMD, while older age, osteoarthritis, higher body weight, and aspirin use were associated with higher spinal BMD.

Conclusion

Maintaining body weight, physical activity, and strength were positively associated with BMD even in very elderly men. Other parameters were also found to influence BMD, and once these were included in multivariate analysis, age was no longer associated with BMD. This suggests that age-related diseases, lifestyle choices, and medications influence BMD rather than age per se.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmö. Osteoporos Int 11(8):669–674

Cummings SR et al (2006) BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res 21(10):1550–1556

Bass E et al (2007) Risk-adjusted mortality rates of elderly veterans with hip fractures. Ann Epidemiol 17(7):514–519

Szulc P et al (2005) Bone mineral density predicts osteoporotic fractures in elderly men: the MINOS study. Osteoporos Int 16(10):1184–1192

Yoshimura N et al (2002) Bone loss at the lumbar spine and the proximal femur in a rural Japanese community, 1990–2000: the Miyama study. Osteoporos Int 13(10):803–808

Hannan MT et al (2000) Risk factors for longitudinal bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 15(4):710–720

Orwoll ES et al (2000) Determinants of bone mineral density in older men. Osteoporos Int 11(10):815–821

Lunt M et al (2001) The effects of lifestyle, dietary dairy intake and diabetes on bone density and vertebral deformity prevalence: the EVOS study. Osteoporos Int 12(8):688–698

Lau EM et al (2006) The determinants of bone mineral density in Chinese men—results from Mr. Os (Hong Kong), the first cohort study on osteoporosis in Asian men. Osteoporos Int 17(2):297–303

Glynn NW et al (1995) Determinants of bone mineral density in older men. J Bone Miner Res 10(11):1769–1777

Chiu G et al (2009) Relative contribution of multiple determinants to bone density in men. Osteoporoisis Int 20:2035–2047

Cauley JA et al (2005) Factors associated with the lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density in older men. Osteoporos Int 16(12):1525–1537

Papaioannou A et al (2009) Risk factors for low BMD in healthy men age 50 years or older: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 20:507–518

Huuskonen J et al (2000) Determinants of bone mineral density in middle aged men: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 11(8):702–708

Nguyen TV, Center JR, Eisman JA (2000) Osteoporosis in elderly men and women: effects of dietary calcium, physical activity, and body mass index. J Bone Miner Res 15(2):322–331

Jones G et al (1994) Progressive loss of bone in the femoral neck in elderly people: longitudinal findings from the Dubbo osteoporosis epidemiology study. Bmj 309(6956):691–695

Dennison E et al (1999) Determinants of bone loss in elderly men and women: a prospective population-based study. Osteoporos Int 10(5):384–391

Burger H et al (1998) Risk factors for increased bone loss in an elderly population: the Rotterdam study. Am J Epidemiol 147(9):871

NHMRC, Australian Alcohol Guidelines: Health Risks and Benefits. Canberra, NHMRC, N.H.a.M.R. Council, Editor. 2001, Commonwealth of Australia

Blyth FM et al (2008) Pain, frailty and comorbidity on older men: the CHAMP study. Pain 140(1):224–230

Fried L et al (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Med Sci 56(3):146

Washburn RA et al (1999) The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol 52(7):643–651

Sherrington C, Lord S (2005) Reliability of simple portable tests of physical performance in older people after hip fracture. Clin Rehabil 19(5):496

Jorm AF (2004) The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): a review. Int Psychogeriatr 16(03):275–293

Szulc P et al (2000) Cross-sectional assessment of age-related bone loss in men: the MINOS study. Bone 26(2):123–1229

Liu H et al (2008) Screening for osteoporosis in men: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Guideline. Ann Intern Med 148(9):685–701

Nguyen ND et al (2007) Development of a nomogram for individualizing hip fracture risk in men and women. Osteoporos Int 18(8):1109–1117

Kanis JA et al (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19(4):385–397

Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT (1995) Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol 142(9):889–903

Turner C et al (2009) Mechanobiology of the skeleton. Science Signaling 2(68):pt3

Frost HM (1999) Why do bone strength and "mass" in aging adults become unresponsive to vigorous exercise? Insights of the Utah paradigm. J Bone Miner Metab 17(2):90–97

Brin I et al (1981) Rapid palatal expansion in cats: effect of age on sutural cyclic nucleotides. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 79(2):162–175

Rubin CT, Bain SD, McLeod KJ (1992) Suppression of the osteogenic response in the aging skeleton. Calcif Tissue Int 50(4):306–313

Srinivasan S et al (2003) Enabling bone formation in the aged skeleton via rest-inserted mechanical loading. Bone 33(6):946–955

Leppänen O et al (2008) Pathogenesis of age-related osteoporosis: impaired mechano-responsiveness of bone is not the culprit. PLoS ONE 3(7):e2540

Cheung E et al (2005) Determinants of bone mineral density in Chinese men. Osteoporos Int 16(12):1481–1486

Lau EM et al (2005) Prevalence of and risk factors for sarcopenia in elderly Chinese men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60(2):213–216

Cauley JA et al (2005) Bone mineral density and the risk of incident nonspinal fractures in black and white women. Jama 293(17):2102–2108

Uzzan B et al (2007) Effects of statins on bone mineral density: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Bone 40(6):1581–1587

Tang Q et al (2008) Statins: under investigation for increasing bone mineral density and augmenting fracture healing. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 17(10):1435–1463

Carbone LD et al (1795) Association between bone mineral density and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin: impact of cyclooxygenase selectivity. J Bone Miner Res 18(10):1795–1802

Yamaza T, Akiyama K, Shi S (2008) Is aspirin treatment an appropriate intervention for osteoporosis? Future Rheumatol 3(6):499–502

Jodar E et al (2001) Bone mineral density in male patients with L-thyroxine suppressive therapy and Graves disease. Calcif Tissue Int 69(2):84–87

Karner I et al (2005) Bone mineral density changes and bone turnover in thyroid carcinoma patients treated with supraphysiologic doses of thyroxine. Eur J Med Res 10(11):480

Sheppard M, Holder R, Franklyn J (2002) Levothyroxine treatment and occurrence of fracture of the hip. Arch Intern Med 162(3):338

Papi G et al (2005) A clinical and therapeutic approach to thyrotoxicosis with thyroid-stimulating hormone suppression only. Am J Med 118(4):349–361

Franco C et al (2009) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with osteoporosis and low levels of vitamin D. Osteoporos Int 20(11):1881–1887

Nuti R et al (2009) Vertebral fractures in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the EOLO study. Osteoporos Int 20(6):989–998

Cumming RG et al (2009) Cohort profile: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP). Int J Epidemiol 38(2):374–378

Holden C, McLaclan R, Pitts M (2005) Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet 366:218–224

Trivedi D, Khaw K (2001) Bone mineral density at the hip predicts mortality in elderly men. Osteoporos Int 12(4):259–265

Fuerst T et al (2009) Evaluation of vertebral fracture assessment by dual X-ray absorptiometry in a multicenter setting. Osteoporos Int 20:1199–1205

Schousboe J et al (2008) Vertebral fracture assessment: the 2007 ISCD official positions. J Clin Densitom 11(1):92–108

Acknowledgements

The CHAMP Study is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC Project Grant No. 301916) and the Ageing and Alzheimer’s Research Foundation (AARF). Kerrin Bleicher’s Ph.D. research is supported by the AARF scholarship. Many thanks to the scientists, Lynley Robinson and Beverly White, for assessing the scans for vertebral deformities.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bleicher, K., Cumming, R.G., Naganathan, V. et al. Lifestyle factors, medications, and disease influence bone mineral density in older men: findings from the CHAMP study. Osteoporos Int 22, 2421–2437 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1478-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1478-9