Abstract

Summary

Attendance at a fragility-fractures-prevention workshop by primary care physicians was associated with higher rates of osteoporosis screening and treatment initiation in elderly female patients and higher rates of treatment initiation in high-risk male and female patients. However, osteoporosis management remained sub-optimal, particularly in men.

Introduction

Rates of osteoporosis-related medical practices of primary care physicians exposed to a fragility-fractures-prevention workshop were compared with those of unexposed physicians.

Methods

In a cluster cohort study, 26 physicians exposed to a workshop were matched with 260 unexposed physicians by sex and year of graduation. For each physician, rates of bone mineral density (BMD) testing and osteoporosis treatment initiation among his/her elderly patients 1 year following the workshop were computed. Rates were compared using multilevel logistic regression models controlling for potential patient- and physician-level confounders.

Results

Twenty-five exposed physicians (1,124 patients) and 209 unexposed physicians (9,663 patients) followed at least one eligible patient. In women, followed by exposed physicians, higher rates of BMD testing [8.5% versus 4.2%, adjusted OR (aOR) = 2.81, 95% CI 1.60–4.94] and treatment initiation with bone-specific drugs (BSDs; 4.8% vs. 2.4%, aOR = 1.95, 1.06–3.60) were observed. In men, no differences were detected. In patients on long-term glucocorticoid therapy or with a previous osteoporotic fracture, higher rates of treatment initiation with BSDs were observed in women (12.0% vs. 1.9%, aOR = 7.38, 1.55–35.26), and men were more likely to initiate calcium/vitamin D (5.3% vs. 0.8%, aOR = 7.14, 1.16–44.06).

Conclusions

Attendance at a primary care physician workshop was associated with higher rates of osteoporosis medical practices for elderly women and high-risk men and women. However, osteoporosis detection and treatment remained sub-optimal, particularly in men.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (1997) Who are candidates for prevention and treatment for osteoporosis? Osteoporos Int 7(1):1–6

Osteoporosis Canada. About osteoporosis: What is osteoporosis? Available from: http://www.osteoporosis.ca/english/About%20Osteoporosis/what-is/default.asp?s=1. Accessed 11 Aug 2008

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Fast facts on osteoporosis. Available from: http://www.nof.org/osteoporosis/diseasefacts.htm. Accessed 11 Aug 2008

Papaioannou A, Giangregorio L, Kvern B et al (2004) The osteoporosis care gap in Canada. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 5:11

Perreault S, Dragomir A, Desgagne A et al (2005) Trends and determinants of antiresorptive drug use for osteoporosis among elderly women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 14(10):685–695

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A et al (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35(5):293–305

Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA et al (2004) Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 15(10):767–778

Goudreau J, Rodrigues I, Lalonde L et al (2005) Faire connaître les recommandations d’un guide de pratiques: développement et évaluation d’une intervention de formation continue. Pédagogie Médicale 6(3):147–159

Brown JP, Josse RG (2002) 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. CMAJ 167(10 Suppl):S1–S34

American Geriatrics Society–British Geriatrics Society–American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention (2001) Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 49(5):664–672

Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. Rapport annuel de gestion 2005-2006. Available from: http://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/publications/documents/rapp0506/rapp_annuel_0506_complet.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2007

Tamblyn R, Lavoie G, Petrella L et al (1995) The use of prescription claims databases in pharmacoepidemiological research: the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the prescription claims database in Quebec. J Clin Epidemiol 48(8):999–1009

Blouin J, Dragomir A, Ste-Marie LG et al (2007) Discontinuation of antiresorptive therapies: a comparison between 1998–2001 and 2002–2004 among osteoporotic women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(3):887–894

Perreault S, Dragomir A, Blais L et al (2008) Population-based study of the effectiveness of bone-specific drugs in reducing the risk of osteoporotic fracture. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 17(3):248–259

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL et al (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288(3):321–333

Brown JP, Fortier M, Frame H et al (2006) Canadian consensus conference on osteoporosis, 2006 update. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 28(2 Suppl 1):S95–S112

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Fracture risk associated with systemic and topical corticosteroids. J Intern Med 257(4):374–384

Gums J, Tovar J (2005) Adrenal gland disorders. In: DiPiro J, Talbert R, Yee G, Matzke G, Wells B, Posey M (eds) Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach, 6th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, p 1403

Pack AM, Morrell MJ (2004) Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy Behav 5(Suppl 2):S24–S29

Wawrzynska L, Tomkowski WZ, Przedlacki J et al (2003) Changes in bone density during long-term administration of low-molecular-weight heparins or acenocoumarol for secondary prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 33(2):64–67

Tamler R, Epstein S (2006) Nonsteroid immune modulators and bone disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1068:284–296

Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P et al (2008) Screening for osteoporosis in men: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 148(9):680–684

Reid RL, Blake J, Abramson B et al (2009) SOGC clinical practice guidelines: Menopause and osteoporosis update 2009. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 31(1):Supplement 1

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J et al (2007) Challenges in improving the quality of osteoporosis care for long-term glucocorticoid users: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 167(6):591–596

Solomon DH, Katz JN, La Tourette AM et al (2004) Multifaceted intervention to improve rheumatologists’ management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 51(3):383–387

Hansen KE, Rosenblatt ER, Gjerde CL et al (2007) Can an online osteoporosis lecture increase physician knowledge and improve patient care? J Clin Densitom 10(1):10–20

Ioannidis G, Thabane L, Gafni A et al (2008) Optimizing care in osteoporosis: the Canadian quality circle project. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:130

Solomon DH, Polinski JM, Stedman M et al (2007) Improving care of patients at-risk for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 22(3):362–367

Solomon DH, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS et al (2007) Osteoporosis improvement: a large-scale randomized controlled trial of patient and primary care physician education. J Bone Miner Res 22(11):1808–1815

Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH et al (2007) Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 167(19):2110–2115

Davis JC, Guy P, Ashe MC et al (2007) HipWatch: osteoporosis investigation and treatment after a hip fracture: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62(8):888–891

Feldstein A, Elmer PJ, Smith DH et al (2006) Electronic medical record reminder improves osteoporosis management after a fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(3):450–457

Cranney A, Lam M, Ruhland L et al (2008) A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with wrist fractures: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int 19(12):1733–1740

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, McAlister FA et al (2008) Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 178(5):569–575

Ashe M, Khan K, Guy P et al (2004) Wristwatch-distal radial fracture as a marker for osteoporosis investigation: a controlled trial of patient education and a physician alerting system. J Hand Ther 17(3):324–328

Lafata JE, Kolk D, Peterson EL et al (2007) Improving osteoporosis screening: results from a randomized cluster trial. J Gen Intern Med 22(3):346–351

Levy BT, Hartz A, Woodworth G et al (2009) Interventions to improving osteoporosis screening: an Iowa Research Network (IRENE) study. J Am Board Fam Med 22(4):360–367

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM et al (1998) Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ 317(7156):465–468

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD et al (1995) Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 274(9):700–705

Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N et al (1999) Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 282(9):867–874

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A (1997) Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ 157(4):408–416

Jaglal SB, Carroll J, Hawker G et al (2003) How are family physicians managing osteoporosis? Qualitative study of their experiences and educational needs. Can Fam Physician 49:462–468

Yuksel N, Majumdar SR, Biggs C et al (2009) Community pharmacist-initiated screening program for osteoporosis: randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int [Epub 2009 Jun 5]

McDonough RP, Doucette WR, Kumbera P et al (2005) An evaluation of managing and educating patients on the risk of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Value Health 8(1):24–31

Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K (1992) A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol 45(2):197–203

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Consortium lavallois de recherche en santé et services sociaux. Lyne Lalonde, Sylvie Perreault, and Lucie Blais are research scholars who receive financial support from the Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec. We thank Chantal Legris for her assistance in the preparation of this article.

Financial disclosure

Consortium lavallois de recherche en santé et services sociaux.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

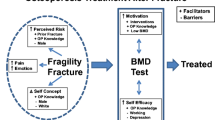

Appendix A

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laliberté, MC., Perreault, S., Dragomir, A. et al. Impact of a primary care physician workshop on osteoporosis medical practices. Osteoporos Int 21, 1471–1485 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1116-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1116-6