Abstract

This paper utilizes time-varying parameters Bayesian vector auto-regression model with stochastic volatility approach to investigate the time-varying dynamic relation between FDI, growth and trade partisan conflict in the US. The empirical results confirm that an increase in trade partisan conflict will deter FDI inflows to the US and discourage economic activities. Besides, we also examine the responses of equity investment, intra-company loans and reinvestment earnings given trade partisan conflict shock. In a robustness check, we consider different measurements on FDI and other control variables. The negative role of a trade partisan conflict shock is not altered, indicating the robustness of the findings. Moreover, trade partisan conflicts like GATT, Omnibus Bill Veto, NAFTA, Bush versus Kerry, the financial crisis and TPP are key factors which affect the dynamics. The US government should remedy the negative impacts of trade policy conflict on FDI inflows and economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The UNCTAD (2019) is available at https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=1980, accessed on 14/03/2019.

The OECD (2018) is available at http://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/FDI-in-Figures-April-2018.pdf, accessed on 14/03/2019.

Based on the referees’ comments, we check the robustness against foreign direct investment, growth rate and interest rate, respectively.

As suggested by the reviewer, we utilize the net FDI inflows in the following analysis as shown in equation (20).

To solve the issue of negative values of FDI, Busse and Hefeker (2007) propose a method which is considered in the following robustness check. Azzimonti (2019) also uses such method to inspect the robustness of estimations against different proxies for foreign direct investment. The results suggest there are no significant changes.

Following Primiceri (2005) and Franta et al. (2014), the effective federal funds rate and 3-month treasury bill entered into the model are in level. To examine the stationarity of other variables, we utilize Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron unit root tests. The stationary results are upon request. All variables used in this paper are shown in “Appendix.”

As Canova and Ciccarelli (2009) suggested, eliciting the priors over the whole sample is reasonable if a training sample is not available. Franta et al. (2014) also use such method to generate the priors because the data of Czech Republic cannot be reached pre-1996. The TPCI is freshly constructed, which is used in few studies. Thus, the priors in this study are actually the estimations on a fixed-coefficient VAR model on the full sample from January 1985 to December 2018.

Primiceri (2005) presents three reasons behind for the choice of the time variation of the coefficients. In short, the model misbehaves by choosing a higher \(k_Q\), especially in forecasting (Stock and Watson 1996). Further, Kirchner et al. (2010) use Monte Carlo simulation to check the fits with different situations.

The sign of the responses of \({\text {EI}}_t\), \({\text {IL}}_t\) and \({\text {RE}}_t\) is imposed like the main model shown in Table 3. Besides, the estimations in this part are based on the sample period from 1982Q1 to 2016Q4.

Abbreviations

- GATT:

-

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

- NAFTA:

-

North American Free Trade Agreement

- TPP:

-

Trans-Pacific Partnership

References

Adkins LC, Moomaw RL, Savvides A (2002) Institutions, freedom, and technical efficiency. South Econ J 69(1):92–108.https://doi.org/10.2307/1061558

Alhakimi SS, Peoples J (2009) Foreign direct investment and domestic wages in the usa. Manch. Sch. 77(1):47–64

Arminen H, Menegaki AN (2019) Corruption, climate and the energy-environment-growth nexus. Energy Econ 80:621–634

Azzimonti M (2016) Does partisan conflict deter fdi inflows to the us? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Azzimonti M (2018a) Partisan conflict and private investment. J Monet Econ 93:114–131

Azzimonti M (2018b) The politics of fdi expropriation. Int Econ Rev 59(2):479–510

Azzimonti M (2019) Does partisan conflict deter fdi inflows to the us? J Int Econ 120(C):162–178

Azzimonti M, Talbert M (2014) Polarized business cycles. J Monet Econ 67:47–61

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2016) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ 131(4):1593–1636

Balcilar M, Akadiri SS, Gupta R, Miller SM (2018) Partisan conflict and income inequality in the united states: A nonparametric causality-in-quantiles approach. Soc Indic Res 142:1–18

Bastiaens I (2016) The politics of foreign direct investment in authoritarian regimes. Int Interact 42(1):140–171

Busse M, Hefeker C (2007) Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. Eur J Polit Econ 23(2):397–415

Büthe T, Milner HV (2008) The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing fdi through international trade agreements? Am J Polit Sci 52(4):741–762

Caldara D, Iacoviello M (2018) Measuring geopolitical risk. FRB International Finance Discussion Paper (1222)

Canova F, Ciccarelli M (2009) Estimating multicountry var models. Int Econ Rev 50(3):929–959

Coan TG, Kugler T (2008) The politics of foreign direct investment: an interactive framework. Int Interact 34(4):402–422

Cogley T, Sargent TJ (2005) Drifts and volatilities: monetary policies and outcomes in the post wwii us. Rev Econ Dyn 8(2):262–302

Creal DD, Wu JC (2017) Monetary policy uncertainty and economic fluctuations. Int Econ Rev 58(4):1317–1354

Driffield N, Karoglou M (2019) Brexit and foreign investment in the UK. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 182(2):559–582

Dunning JH (1973) The determinants of international production. Oxf Econ Papers 25(3):289–336

Dunning JH (1980) Toward an eclectic theory of international production: some empirical tests. J Int Bus Stud 11(1):9–31

Franta M, Horváth R, Rusnak M (2014) Evaluating changes in the monetary transmission mechanism in the Czech Republic. Empir Econ 46(3):827–842

Fry R, Pagan A (2011) Sign restrictions in structural vector autoregressions: a critical review. J Econ Lit 49(4):938–60

Ghazalian PL, Amponsem F (2018) The effects of economic freedom on fdi inflows: an empirical analysis. Appl Econ 51:1–22

Gulen H, Ion M (2015) Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Rev Financ Stud 29(3):523–564

Gupta R, Pierdzioch C, Selmi R, Wohar ME (2018) Does partisan conflict predict a reduction in us stock market (realized) volatility? Evidence from a quantile-on-quantile regression model. North Am J Econ Fin 43:87–96

Hajko V, Sebri M, Al-Saidi M, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2018) The energy-growth nexus: history, development, and new challenges. In: The economics and econometrics of the energy-growth Nexus, Elsevier, pp 1–46

Handley K, Limão N (2017) Policy uncertainty, trade, and welfare: theory and evidence for china and the united states. Am Econ Rev 107(9):2731–83

Hartzmark SM (2016) Economic uncertainty and interest rates. Rev Asset Pricing Stud 6(2):179–220

Helpman E (1984) A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. J Polit Econ 92(3):451–471

Husted L, Rogers JH, Sun B (2017) Monetary policy uncertainty. FRB International Finance Discussion Paper (1215)

Inglesi-Lotz R (2018) The role of potential factors/actors and regime switching modeling. In: The economics and econometrics of the energy-growth nexus, Elsevier, pp 113–139

Jiang X, Shi Y (2018) Does us partisan conflict affect US–China bilateral trade? Int Rev Econ Fin https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2018.12.005

Kirchner M, Cimadomo J, Hauptmeier S (2010) Transmission of government spending shocks in the euro area: time variation and driving forces

Krugman P, Venables AJ (1995) Globalization and the inequality of nations. Q J Econ 110(4):857–880

Li Q, Resnick A (2003) Reversal of fortunes: democratic institutions and foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries. Int Org 57(1):175–211

Lucas RE (1990) Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? Am Econ Rev 80(2):92–96

Markusen JR (1984) Multinationals, multi-plant economies, and the gains from trade. J Int Econ 16(3–4):205–226

Mayer M, Kenter R, Morris JC (2015) Partisan politics or public-health need? An empirical analysis of state choice during initial implementation of the affordable care act. Polit Life Sci 34(2):44–51

Menegaki A (2018) The economics and econometrics of the energy-growth nexus. Academic Press, London

Mishra BR, Jena PK (2019) Bilateral fdi flows in four major asian economies: a gravity model analysis. J Econ Stud 46(1):71–89

Ohlin B (1952) Interregional and international trade, vol 39. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Owen E (2015) The political power of organized labor and the politics of foreign direct investment in developed democracies. Comp Polit Stud 48(13):1746–1780

Primiceri GE (2005) Time varying structural vector autoregressions and monetary policy. Rev Econ Stud 72(3):821–852

Rodrik D, Subramanian A, Trebbi F (2004) Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. J Econ Growth 9(2):131–165

Sommer J (2017) Trump immigration crackdown is great for private prison stocks. The New York Times

Stock JH, Watson MW (1996) Evidence on structural instability in macroeconomic time series relations. J Bus Econ Stat 14(1):11–30

Zhou J, Latorre MC (2014) The impact of foreign direct investment on the production networks between China and East Asia and the role of the USA and the rest of the world as final markets. Global Econ Rev 43(3):285–314

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Work on this paper is supported by Australian Government International Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and University Postgraduate Award (UPA).

Appendix A: Variables and sources for the US data

Appendix A: Variables and sources for the US data

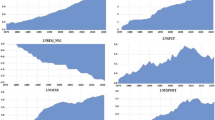

See Fig. 9.

In this appendix, we present the details of variables and sources for US data.

-

\({\text {FDIF}}_t\): Foreign direct investment flow in the USA from the rest of the world. In millions of dollars, quarterly, seasonally adjusted (annual rate). Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {CFDIP}}_t\): Foreign direct investment levels in the USA from the rest of the world. In millions of dollars, quarterly, not seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {EI}}_t\): Equity investment flow in the USA from the rest of the world. Millions of dollars, quarterly, seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1982Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {IL}}_t\): Intra-company debt of US affiliates’ liabilities; asset, flow, millions of dollars, quarterly, seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1982Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {RE}}_t\): Rest of the world; foreign direct investment in the USA: reinvested earnings; asset (current cost), flow, millions of dollars, quarterly, seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1982Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {GR}}_t\): US real GDP growth. Corresponds to real gross domestic product, percent change from quarter one year ago, quarterly, seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {IR}}_t\): Effective federal funds rate, percent, quarterly, not seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {IPG}}_t\): Industrial Production Index, percent change from year ago, quarterly, seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

-

\({\text {TB}}_t\): 3-month treasury bill, secondary market rate, percent, quarterly, not seasonally adjusted. Source: FRED Economic data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Web site: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/. Time span: 1981Q1–2016Q4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Menegaki, A. FDI, growth and trade partisan conflict in the US: TVP-BVAR approach. Empir Econ 60, 1335–1362 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01795-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01795-1