Abstract

Business confidence is a well-known leading indicator of future output. Whether it has information about future investment is, however, unclear. We determine how informative business confidence is for investment growth independently of other variables using US business confidence survey data for 1955Q1–2016Q4. Our main findings are: (i) business confidence has predictive ability for investment growth; (ii) remarkably, business confidence has superior forecasting power, relative to conventional predictors, for investment downturns over 1–3-quarter forecast horizons and for the sign of investment growth over a 2-quarter forecast horizon; and (iii) exogenous shifts in business confidence reflect short-lived non-fundamental factors, consistent with the ‘animal spirits’ view of investment. Our findings have implications for improving investment forecasts, developing new business cycle models, and studying the role of social and psychological factors determining investment growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Historically, the view that behavioural factors may influence investment decisions has been around at least since Keynes (1936) who famously invoked ‘animal spirits’ as an inducement to invest and noted: “But individual initiative will only be adequate when reasonable calculation is supplemented and supported by animal spirits.”(Chap 12, page 163).

Appendix provides details on how the business confidence index is constructed.

Rossi (2013) points out that it is not necessary for the in-sample results to be similar to OOS results.

This definition is similar to that in Taylor and McNabb (2007) for output downturns.

Online Appendix available at https://carleton.ca/economics/wp-content/uploads/cep17-13.pdf provides the details of data construction and sources.

To save space, we have put all the associated Tables and Figures from this section in Appendix.

Chirinko and Schaller (2001) also use neoclassical model where dependent variable is investment rate and the regressors are the level and lag of change in output, the level and lag of change in the cost of capital and liquidity, where liquidity is retained earnings plus depreciation.

Allowing for different lags for different sets of variables in (2) does not affect our empirical findings (the results are available upon request).

The general setup for obtaining OOS data is similar to Estrella and Mishkin (1998).

The results for the rolling-window estimation are available upon request. Notably, the recursive estimation scheme performs better for structures investment, and with statistical significance, relative to the rolling-window estimation.

This definition is similar to that used for output downturns in Taylor and McNabb (2007).

Previously, the probit model has been used by Estrella and Mishkin (1998), Kauppi and Saikkonen (2008), Nyberg (2010), Christiansen et al. (2014), Chen et al. (2016), among others, to forecast recessions. The main difference relative to these papers and other previous research is that our focus is on investment downturns, not output recessions.

We consider dynamic probit model in the robustness section.

The results based on the alternative approach of rolling-window estimation are available upon request.

Nyberg (2010) uses nine months lags of the dependent variable (recession indicator) due to the NBER announcement delay.

References

Ang JB (2010) Determinants of private investment in Malaysia: what causes the post-crisis slumps? Contemp Econ Policy 28:378–391

Angeletos G-M, Collard F, Dellas H (2018) Quantifying confidence. Econometrica 86(5):1689–1726

Barro RJ (1990) The stock market and investment. Rev Financ Stud 3:115–131

Barsky RB, Sims ER (2012) Information, animal spirits, and the meaning of innovations in consumer confidence. Am Econ Rev 102:1343–1377

Berge TJ, Jordà Ò (2011) Evaluating the classification of economic activity into recessions and expansions. Am Econ J Macroecon 3:246–277

Bram J, Ludvigson SC (1998) Does consumer confidence forecast household expenditure? A sentiment index horse race. Econ Policy Rev 4:59–78

Carriero A, Clark TE, Marcellino M (2015) Bayesian VARs: specification choices and forecast accuracy. J Appl Econ 30:46–73

Carroll CD, Fuhrer JC, Wilcox DW (1994) Does consumer sentiment forecast household spending? If so, why? Am Econ Rev 84:1397–1408

Chen S-S, Chou Y-H, Yen C-Y (2016) Predicting US recessions with stock market illiquidity, B.E. J Macroecon (Contrib) 16:93–123

Chirinko RS, Schaller H (2001) Business fixed investment and “bubbles”: the Japanese case. Am Econ Rev 91:663–680

Christiansen C, Eriksen JN, Møller SV (2014) Forecasting US recessions: the role of sentiment. J Bank Finance 49:459–468

Christoffersen PF, Diebold FX (2006) Financial asset returns, direction-of-change forecasting, and volatility dynamics. Manag Sci 52:1273–1287

Christoffersen PF, Diebold FX, Mariano RS, Tay AS, Tse YK (2007) Direction-of-change forecasts based on conditional variance, skewness and kurtosis dynamics: International evidence. J Financ Forecast 1:1–22

Clark TE, West KD (2007) Approximately normal tests for equal predictive accuracy in nested models. J Econom 138:291–311

Cotsomitis JA, Kwan AC (2006) The usefulness of consumer confidence in forecasting household spending in Canada: a national and regional analysis. Econ Inq 44:185–197

Dasgupta S, Lahiri K (1993) On the use of dispersion measures from NAPM surveys in business cycle forecasting. J Forecast 12:239–253

Diebold FX, Rudebusch GD (1989) Scoring the leading indicators. J Bus 62:369–391

Estrella A (1998) A new measure of fit for equations with dichotomous dependent variables. J Bus Econ Stat 66:198–205

Estrella A, Mishkin FS (1998) Predicting US recessions: financial variable as leading indicators. Rev Econ Stat 80:45–61

Fuhrer JC (1993) What role does consumer sentiment play in the US macroeconomy? New Engl Econ Rev 32–44

Gilchrist S, Himmelberg CP (1995) Evidence on the role of cash flow for investment. J Monet Econ 36:541–572

Gilchrist S, Zakrajšek E (2012) Credit spreads and business cycle fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 102:1692–1720

Goyal A, Welch I (2003) Predicting the equity premium with dividend ratios. Manag Sci 49:639–654

Goyal A, Welch I (2008) A comprehensive look at the empirical performance of equity premium prediction. Rev Financ Stud 21:1455–1508

Hall RE, Jorgenson DW (1969) Tax policy and investment behavior: reply and further results. Am Econ Rev 59:388–401

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1982) The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36

Heye C (1993) Labor market tightness and business confidence: an international comparison. Polit Soc 21:169–193

Jorgenson DW (1963) Capital theory an investment behavior. Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 59:247–259

Kauppi H, Saikkonen P (2008) Predicting US recessions with dynamic binary response models. Rev Econ Stat 90:777–791

Keynes JM (1936) The general theory of employment, interest, and money. Palgrave McMillan, Basingstoke

Lahiri K, Monokroussos G, Zhao Y (2016) Forecasting consumption: the role of consumer confidence in real time with many predictors. J Appl Econ 31:1254–1275

Leeper E (1992) Consumer attitudes: king for a day. Fed Reserve Bank Atlanta Econ Rev 77:1–15

Liu W, Moench E (2016) What predicts US recessions? Int J Forecast 32:1138–1150

Ludvigson SC (2004) Consumer confidence and consumer spending. J Econ Perspect 18:29–50

Matsusaka JG, Sbordone AM (1995) Consumer confidence and economic fluctuations. Econ Inq 32:296–318

Nyberg H (2010) Dynamic probit models and financial variables in recession forecasting. J Forecast 29:215–230

Nyberg H (2011) Forecasting the direction of the US stock market with dynamic binary probit models. Int J Forecast 27:561–578

Pesaran MH, Timmermann A (2009) Testing dependence among serially correlated multicategory variables. J Am Stat Assoc 485:325–337

Pönkä H (2017a) Predicting the direction of US stock markets using industry returns. Empir Econ 52:1451–1480

Ponka H (2017b) The role of credit in predicting US recessions. J Forecast 36:469–482

Rapach DE, Wohar ME (2007) Forecasting the recent behavior of US business fixed investment spending: an analysis of competing models. J Forecast 26:33–51

Rossi B (2013) Advances in forecasting under model instability. Handb Econ Forecast 2:1203–1324

Taylor K, McNabb R (2007) Business cycles and the role of confidence: evidence for europe. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 69:185–208

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank three anonymous referees, Patrick Coe, Lilia Karnizova, Lynda Khalaf, Konstantinos Metaxoglou and participants at the Canadian Economic Association Conference, 2017 at Antigonish, Nova Scotia for comments.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data construction and source

Business confidence index We obtain the business confidence index from the OECD’s leading indicator database. The OECD collects business confidence data, based on business tendency survey of manufacturing activity, from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM).Footnote 21 The business confidence series refers to PMI (previously, PMI referred to the Purchasing Managers’ Index), which is based on Manufacturing ROB. The PMI is an equally weighted (20% each) composite index of five seasonally adjusted diffusion indices, namely new orders, production, employment, supplier deliveries and inventories. An index value of over 50 represents growth or expansion within the manufacturing sector of the economy compared with the prior month and a value of under 50 indicates contraction. The OECD converts the PMI diffusion index into a net balance (in %) for cross-country consistency.

Real business investment and its components The real business investment corresponds to the private non-residential fixed investment and its components are non-residential structure, equipment and intellectual property products. We obtain the data from NIPA Table 1.1.3 of BEA. Real gross domestic product We obtain the data for the real gross domestic product from NIPA Table 1.1.3 of BEA.

Price index of gross domestic product We obtain the data for the price index of real gross domestic product from NIPA Table 1.1.4 of BEA.

Price index of business investment We obtain the data for the price index of real business investment from NIPA Table 1.1.4 of BEA.

Real lending rate It is the prime business rate of commercial bank. We obtain the data from Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

We calculate the real lending rate as an ex post measure as follows:

where R is the real lending rate.

User cost of capital We measure the user cost of capital following Chirinko and Schaller (2001) and Ang (2010), which is similar to the Hall and Jorgenson (1969). The user cost of capital is as follows:

where DEP is the depreciation. We fix the DEP as 5%.

Real cash flow It is the net cash flow with Inventory Valuation Adjustment (IVA) divided by the price index of gross domestic product. We obtain from Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Source: BEA.

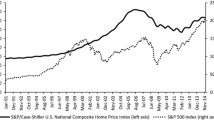

Stock market price It is the monthly S&P 500 index divided by the price index of gross domestic product. We collect from Yahoo!Finance.Footnote 22

Term spread It is the monthly rate of 10-year government bond minus the monthly rate of 3-month treasury bill. We obtain from Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Credit spread It is the Moody’s Baa corporate bond yield minus the Moody’s Aaa corporate bond yield. We obtain from Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

1.2 SR calculation

The calculation of SR is as:

where \(\hat{g_t}\), u and d are the forecast of \(g_t\), upward signal and downward signal, respectively.

1.3 Additional models for downturns and direction of investment

Table 13 contains the results to assess the robustness whether BCI has independent forecasting power for business investment downturns, after controlling for other relevant predictors. Panel (a) shows that BCI-nested model performs better than BCI non-nested model for 1–4-quarter horizons. The result suggests that BCI has additional information to forecast investment downturns, after controlling for conventional predictors, TS and \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\) of recessions. Panel (b) shows that BCI-nested model is superior than BCI non-nested model for all forecast horizons, where we control for CS and \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\). We next consider CS, \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\) and \(\Delta \hbox {GDP}\) as control variables and show the results in panel (c). This result is also consistent with previous result and implies that BCI has independent information to forecast the investment downturns for 1–4-quarter horizons.

Finally, we use different control variables to evaluate whether BCI forecast for direction of investment growth independently. Table 14 shows the results. Panel (a) shows that BCI-nested model is better than BCI non-nested model for 1- and 3-quarter forecast horizons, suggesting that BCI has independent information to explain the direction of investment, controlling for conventional predictors, TS and \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\). We then control for CS and \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\) and show the results in panel (b). The results show that BCI-nested model has better performance than BCI non-nested model for 1- and 4-quarter horizons. Panel (c) also shows the results after controlling for three predictors, CS, \(\Delta \hbox {SP}\) and \(\Delta \hbox {GDP}\) and suggests that BCI has additional information to explain the direction of investment for 2-quarter horizons (Table 15).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, H., Upadhayaya, S. Does business confidence matter for investment?. Empir Econ 59, 1633–1665 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01694-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01694-5