Abstract

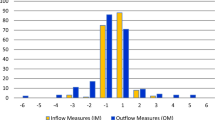

The implementation of macroprudential policies for improving a country’s financial stability has become more common in emerging markets. The aim of this paper is to analyse the effect of macroprudential policy on both capital flow volatility and price stability in emerging market economies. The analysis covers the Global Financial Crisis and post-crisis period. The effects of general macroprudential variables including leverage growth and credit growth and specific instruments, namely loan-to-value caps and reserve requirements on capital inflow, capital outflow and price stability have been tested. Propensity score matching techniques have been used to measure the effectiveness of various macroprudential policy measures on capital flow volatility. Major findings indicate monetary policy instruments are effective in pursuing both monetary policy objectives and macroprudential objectives. Short-term capital account volatility is seen to respond to macroprudential policy instruments. Propensity score matching was only successfully implemented for capital volatility. Results show that increased measures for macroprudential policy are effective for capital outflow and, decreased measures for macroprudential policy are effective, to a lesser extent, for capital inflows. Furthermore, meaningful correlation between increased macroprudential measures during periods of tight monetary policy exists only for capital outflows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of macroprudential in published research databases was small due to lags in the publication process (see Galati and Moessner 2011). Therefore, the large majority of the literature review and references in this area were from the working paper series.

It mirrors the risk-taking attitudes or market risk premiums.

See Appendix 6.1 for a detailed explanation of the variables used in the estimation equations.

Unit root test results show that all variables other than VIX and banking sector leverage ratio are found stationary.

This study followed Forbes et al. (2015) and used logit instead of probit model in order to “spread out” the density of scores at very low and high propensity scores. There are seven covariates used.

The share of bond market funding in the USA was more than 50% in 2007, and it was increased to 70% in 2014. This was 14% in euro area in 2007 and increased to 21% in 2014. We see similar trends in emerging markets. For example, in Latin America, it increased from 27% in 2007 to 42% in 2014; in Asian markets, it increased from 25% in 2007 to 35% in 2014. Nevertheless, the share of non-financial corporate indebtedness to GDP in 2000 was around 89% in mature markets and 53% in emerging markets. In 2014, this increased to 95% in mature markets and more than 80% in emerging markets (see IFF 2015, p. 3).

LTV, RR and other instruments are used to represent endogenous variables in binary regression.

References

Ahmed S, Zlate A (2013) Capital flows to emerging market economies: a brave new world? Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System International Finance, discussion papers 1081

Akinci O, Olmsted-Rumsey R (2015) How effective are macroprudential policies? An empirical investigation. International finance discussion papers 1136

Angelini P, Neri S, Panetta F (2012) Monetary and macroprudential policies. European Central Bank, working paper series no. 1449

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Augouleas E (2015) Bank leverage ratios and financial stability: a micro- and macroprudential perspective. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, working paper no. 849

Bank of International Settlements (1986) Recent innovations international banking. Report prepared by a study group established by the central banks if the Group of Ten countries, Basel, April (cross report)

Blunden G (1987) Supervision and central banking. Bank Engl Q Bull 27:380–385

Bogdanov B (2014) Liberalised capital accounts and volatility of capital flows and foreign exchange rates. European economy economic papers 521

Bose N (2002) Inflation, the credit market and economic growth. Oxf Econ Pap 54(3):412–434

Bruno V, Shim I, Shin HS (2015) Comparative assessment of macroprudential policies, BIS working paper no 502

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2005) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. IZA discussion paper series, IZA DP no. 1588

Cline W (2010) Financial globalisation, economic growth, and the crisis of 2007–2009. Peterson Institute of International Economics, Washington

Crockett AD (2000) Marrying the micro- and macro-prudential dimensions of financial stability. In: BIS management speeches before the eleventh international conference of banking supervisors, Basel, 20–21 September 2000

Fernández-Arias E, Montiel PJ (1996) The surge in capital inflows to developing countries: an analytical Overview. World Bank Rev 10(1):51–77

Forbes KJ (2007) The microeconomic evidence on capital controls: no free lunch. In: Edwards Sebastian (ed) Capital controls and capital flows in emerging economies: policies, practices, and consequences. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 171–202

Forbes K, Klein M (2013) Pick your poison: The choices and consequences of policy responses to crises. MIT-Sloan Working Paper 5061-13.

Forbes KJ, Warnock FE (2011) Capital flow waves: surges, stops, flight, and retrenchment. NBER working paper series, working paper 17351

Forbes KJ, Fratzscher M, Straub R (2015) Capital flow management measures: what are they good for? J Int Econ 99:76–97

Gagnon JE (2011) Flexible exchange rates for a stable world economy. Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economies, Washington

Galati G, Moessner R (2011) Macroprudential policy—a literature review. BIS working papers no 337

Galati G, Moessner R (2014) What do we know about the effects of macroprudential policy? DNB working paper no. 440

Glick R, Guo X, Hutchison M (2006) Currency crises, capital-account liberalisation, and selection bias. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):698–714

Gourinchas P-O, Jeanne O (2006) Capital flows to developing countries: allocation puzzle. Working paper 13602, National Bureau of Economic Research

Hansen LP (1982) Large sample properties of generalised method of movements estimators. Econometrica 50:1029–1054

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA (2007) Matching as nonparametric pre-processing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal 15:199–236

IMF (2012) The liberalisation and management of capital flows: an institutional view. IMF, Washington

IMF (2013a) The interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies. International Monetary Fund, Washington

IMF (2013b) Unconventional monetary policies—recent experience and prospects. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Institute of International Finance (IIF) (2015) Capital markets monitor: key issues. IIF, Washington

Kawata H, Kurachi Y, Nakamura K, Teranisi Y (2013) Impact of macroprudential policy measures on economic dynamics. Bank of Japan, working paper series no. 13-E-3

Klein M (2012) Capital controls: gates versus walls. Brook Pap Econ Act, Fall, pp 317–355

Lechner M (2002) Some practical issues in the evaluation of heterogenous labour market programmes by matching methods. J R Stat Soc 165:59–82

Lim C, Columba F, Costa A, Kongsamut P, Otani A, Saiyid M, Wezel T, Wu X (2011) Macroprutential policy: what instruments and how to use them? Lessens from country experiences. IMF working paper W/11/238. International Monetary Fund

Miranda-Agrippino S, Rey H (2012) World asset markets and global liquidity. Presented at the Frankfurt ECB BIS conference, February 2012, mimeo, London Business School

Morgan SL, Windship C (2015) Counterfactuals and causal inference: methods and principles for social research, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nier E, Sedik TS, Mondino T (2014) Gross private capital flows to emerging markets: can the global financial cycle be tamed? IMF working paper WP/14/196

Ostry JD, Ghosh AR, Chamon M, Qureshi MS (2012) Tools for managing financial stability risks from capital inflows. J Int Econ 88(2):407–421

Pearl J (2010) The foundations of causal inference. Soc Methodol 40:75–149

Powell HJ (2013) Advanced economy monetary policy and emerging market economies. In: Speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 20123 Asia economic policy conference

Prasad ES, Rajan RG, Subramanian A (2007) Foreign capital and economic growth. Brook Pap Econ Act 38:153–230

Rey H (2013) Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. In: Mimeo Kansas FED Jackson Hole conference, Wyoming, August 22–24

Rodman D (2006) An introduction to “difference” and “system” GMM in Stata. Center for Global Development WP 103

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Shim I, Bogdanova B, Shek J, Subeluyte A (2013) Database for policy actions on housing markets. BIS quarterly review, BIS

Shin HS (2012) Adapting macroprudential policies to global liquidity conditions. J Econ Chil (Chil Econ) 15(2):33–65

Sianesi B (2001) Implementing propensity score matching with STATA. Presentation at the UK Stata Users Group, VII meeting, London

Taylor MP, Sarno L (1997) Capital flows to developing countries: long- and short-term determinants. World Bank Rev 11(3):451–470

Unsal F (2011) Capital flows and financial stability: monetary policy and macroprudential responses. IMF working paper WP/11/189

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data

There are 25 countries included in this analysis. These are Albania, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, Turkey and Uruguay. The data range covers 2008Q1–2013Q4. All data have been obtained from International Monetary Fund (IMF) International Financial Statistics (IFS), national central banks and national statistical departments. Details for the sources of data are listed below.

Capital inflow (KAI) and outflow (KAO): Portfolio investment inflow and outflow are used and data were obtained from the IMF.

GDP: Data for Argentina and Mexico was obtained from OECD; for all other countries, data were obtained from the IMF.

Interest rate (1): 3-month interbank rate for Poland, Romania Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania, obtained from Eurostat. Bolivia, India, China, Hong Kong obtained from central banks. Others are monetary policy-related interest rates from IMF.

VIX: Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) Rate Market Volatility Index obtained from Bloomberg and CBOE.

Leverage growth (LEV): Banking leverage is calculated by claims on private sector divided by the sum of transferable deposits included in broad money and other deposits included in broad money. Data obtained from IMF. However, IMF data are not available for Czech Republic, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Latvia, Lithuania and Singapore. Therefore, domestic economy leverage (domestic credits divided by GDP) was used and data were obtained from central banks and national statistical departments.

Domestic credit growth (CR): Domestic credits include the sum of net claims on central government, claims on other financial corporations, claims on public non-financial corporations and claims on private sector (for Bulgaria, only net claims on central government is used due to availability). Data for Bulgaria, Hong Kong, India, Latvia, Lithuania, Peru, Poland and Singapore obtained from national statistical departments, others from the IMF.

Loan-to-value (LTV) and reserve requirements (RR): Dummy variables are used when there are policy changes, obtained from national central banks and other sources (Lim et al. 2011; Shim et al. 2013).

Exchange rates (EXR): Nominal exchange rates, national currency per US dollars, obtained from IMF International Financial Statistics.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uz Akdogan, I. The effects of macroprudential policies on managing capital flows. Empir Econ 58, 583–603 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1541-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1541-5