Abstract

Earlier studies do not agree on whether ethnic identity, i.e., immigrants’ attachment to the home country and the host country, can explain lower employment outcomes among immigrants. This study investigates the relationship between employment and ethnic identity and complements the literature by capturing a novel dimension of ethnic identity: openness to majority norms. Reproducing measures from earlier studies, I find that immigrants’ employment outcomes do not systematically associate with their ethnic identity. However, immigrants who share social norms with the majority experience significantly better employment outcomes, particularly first-generation immigrant women. Furthermore, I show that interethnic differentials in majority norms could account for up to 20 % of the explained part of the employment gap between natives and first-generation immigrants. Those results shed more light on the interethnic employment gap and aspects of immigrants’ identity relevant to economic integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Denmark, the 2008 European Values Survey reveals that one of the biggest concerns associated with immigration is the undermining of the majority culture, and only 6 % of the Danish population wishes that immigrants keep their customs and traditions. This evidence points toward public preferences for an assimilation policy. See also Gundelach (2011).

Sen (1977) represents a pioneer work in the economics of identity literature. Again, see Constant and Zimmermann (2011) for a thorough presentation of the more general literature on the economics of identity. The work of Akerlof and Kranton (2000) constitutes a major reference for recent works linking identity choice and economic outcomes among immigrants. For instance, their model has been used by Fryer and Levitt (2004) to explain the utility associated with the choice of distinctive names among black communities in the USA.

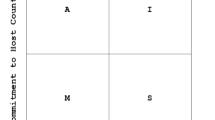

See Constant et al. (2009) for further details on the construction of the ethnosizer. One innovation of the ethnosizer is to measure ethnic identity in two dimensions, placing individual identity relative to both the home and the host countries.

In this paper, the term immigrants designates both first- and second-generation immigrants. The EGV definition of group ancestry equates that of Statistics Denmark. First-generation immigrants were born abroad of parents without Danish citizenship and born outside Denmark. Second-generation immigrants are born in Denmark and none of their parents are both Danish citizen and born in Denmark. If one or both parents born in Denmark become Danish by naturalization, their children will not be second-generation immigrants anymore but natives. If both parents born in Denmark hold their foreign citizenship, their children will be second-generation immigrants. I call second-generation immigrants alternatively descendants.

Gundelach and Nørregård-Nielsen excluded countries of origin close to Denmark in terms of values but largely represented in the immigrant population in 2005 such as Norway and Germany. See Gundelach and Nørregård-Nielsen (2007) for more details on the data set construction.

This period coincides with the international crisis that followed the publication of Mohammed cartoons in a Danish newspaper. Although this crisis could have influenced respondents’ answers, statistics from the EGV data cannot depict major differences in responses before and after the cartoon publication date.

Given that 2006 corresponds to one of the lowest unemployment rates within the past 30 years in Denmark (4.5 % of the total workforce in June 2006, Statistics Denmark (2006), one may fear that a selection of non-working immigrants may have occurred among the survey respondents. In fact, the opposite is true. As found for other surveys conducted among immigrants in different countries (Deding et al. 2008), one can rather observe an overrepresentation of immigrants in employment in the EGV survey.

The EGV survey asks also how many grades (in all education categories) were completed in the home country. The average is around 8.5 (standard deviation 4.3) for both male and female first-generation immigrants. Adding the number of grades from the home country does not appear significant and does not change the results.

A standard factor analysis shows that, even though the variance does not vary much across the four dimensions, the first dimension on the tolerance of some actions and the fourth dimension on gender equality explain most of the variance. See Fig. A1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material for a graphic representation of immigrant shares across the values of the modernization index.

Yet, once the first-generation sample is restricted to Turkish and Pakistanis, the only origins observed for second generations, males from the second generation classify more often as highly modern than males from the first generation of the same origin (see Fig. A2 of the Electronic Supplementary Material).

Tolerance toward abortion, divorce, or homosexuality correlates negatively with the degree of religiosity—the raw coefficient for the whole sample is −0.3. Accordingly, I control simultaneously for religious and a high modernization index in the employment equations.

Origin of regular contacts and language spoken at home constitute two dimensions of the Constant et al. (2009) ethnosizer index. The reproduction of the ethnosizer was considered but abandoned due to a high correlation between employment and interactions measures and the non-availability of pre-study employment information. Nevertheless, in the estimations, I keep the two dimensions of contacts and language as alternative indirect identity measures.

Yet, this pattern does not hold when restricting the first-generation sample to Turkish and Pakistani immigrants (results are not shown but are available from the author).

Looking at simple correlation teaches us that the modernization index only associates with measures of ethnic identity with coefficients below 0.25 for most of them (see Table A1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material).

Other works, however, show that age, time of arrival, and years spent in the country also can shape ethnic identity (Casey and Dustmann 2010).

Running separate models for male and female descendants leads to similar results in terms of associations between employment, ethnic identity, and norms adoption, but due to a significant loss in the number of observations, the statistical significance of other covariates such as education becomes less stable (see Table A2 of the Electronic Supplementary Material). Furthermore, in estimations not shown here, I exclude first-generation immigrants above the age of 35 (upper limit for the descendant sample) and do find very similar results.

Simultaneous endogeneity between employment and, in particular, ethnic identity measured with regular contacts is very likely.

Response bias, including social desirable responding, constitutes a major issue in self-reports on individual attitudes and behaviors (Paulhus 1991).

As results from the previous section show that modernization and religious correlate significantly with employment only for first-generation immigrants, I decompose the employment gap for this group only.

F is the cumulative distribution function from the logistic estimation. Yet, to remain consistent with the previous results, I also employ probit functions to decompose the employment gap.

The ethnic inequality literature often interprets the latter term as actual ethnic discrimination but, as Aaberhardt et al. (2010) discuss, the term unexplained is more appropriate.

Following Jann (2006), I also use weights from a pooled sample of both first-generation immigrants and ethnic Danes. Moreover, weights from this pooled sample were computed after controlling for additional immigrant characteristics. Finally, weights from a larger pooled sample including the two immigrant generations and natives were used. Those robustness checks are shown in Table A6 (Electronic Supplementary Material) and present estimates similar in size and statistical precision.

A recent Danish investigation shows employees’ preference for working with individuals of the same ethnicity (Rockwool Foundation Research Unit 2011).

References

Aaberhardt R, Fougère D, Pouget J, Rathelot R (2010) Wages and employment of French workers with African origin. J Popul Econ 23:881–905

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115:715–753

Alfieri AC, Matthiesen J (2005) Immigrants in Denmark: improving integration to sustain the welfare state. Economic analysis from the European Commission’s Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs 2:19. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication1355_en.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2012

Andersen PB, Lüchau P (2011) Islam and labor market integration in Denmark. In: Hjelm T (ed) Religion and social problems. Routledge, New York, pp 32–49

Battu H, Zenou Y (2010) Oppositional identities and employment for ethnic minorities: evidence from England. Econ J 120:52–71

Battu H, Mwale M, Zenou Y (2007) Oppositional identities and the labor market. J Popul Econ 20:643–667

Berry JW (1997) Immigration acculturation and adaptation (lead article). Appl Psychol: Int Rev 46:5–34

Bevelander P, Veenman J (2006) Naturalisation and employment integration of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands. J Int Migr Integr 7:327–349

Bisin A, Patacchini E, Verdier T, Zenou Y (2011) Ethnic identity and labor-market outcomes of immigrants in Europe. Econ Policy 26:57–92

Borjas GJ (1985) Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. J Labor Econ 3:463–489

Braakmann N (2009) The role of psychological traits for the gender gap in full-time employment and wages: evidence from Germany. German Socio-Economic Panel papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research WP 162

Carlsson M, Eriksson S (2012) Do reported attitudes towards immigrants predict ethnic discrimination? Uppsala University Department of Economics Working Paper Series WP 2012:6

Carlsson M, Rooth DO (2007) Evidence of ethnic discrimination in the Swedish labor market using experimental data. Labour Econ 14:716–729

Carlsson M, Rooth DO (2012) Revealing taste-based discrimination in hiring: a correspondence testing experiment with geographic variation. Appl Econ Lett 19:1861–1864

Casey T, Dustmann C (2010) Immigrants’ identity economic outcomes and the transmission of identity across generations. Econ J 120:31–51

Chiswick BR (1978) The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. J Polit Econ 86:897–922

Constant A, Massey DS (2003) Self-selection, earnings, and out-migration: a longitudinal study of immigrants to Germany. J Popul Econ 16:631–653

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2008) Measuring ethnic identity and its impact on economic behavior. J Eur Econ Assoc 6:424–433

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2009) Work and money: payoffs by ethnic identity and gender. Res Labor Econ 29:3–30

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2011) Migration ethnicity and economic integration. In: Jovanovic MN (ed) International handbook of economic integration. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 145–168

Constant A, Gataullina L, Zimmermann L, Zimmermann KF (2006) Clash of cultures: Muslims and Christians in the ethnosizing process. IZA DP 2350

Constant A, Gataullina L, Zimmermann KF (2009) Ethnosizing immigrants. J Econ Behav Organ 69:274–287

Deding M, Fridberg T, Jakobsen V (2008) Non-response in a survey among immigrants in Denmark. Surv Res Methods 2:107–121

Fairlie RW (1999) The absence of the African-American owned business: an analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. J Labor Econ 17:80–108

Fairlie RW (2005) An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. J Econ Soc Meas 30:305–316

Fryer RG, Levitt SD (2004) The causes and consequences of distinctively black names. Q J Econ 119:767–805

Gundelach P (2011) Små og Store Forandringer—Danskernes Værdier siden 1981. Hans Reitzel, Copenhagen

Gundelach P, Nørregård-Nielsen E (2007) Etniske Gruppers Værdier—Baggrundsrapport. Tænketanken om udfordringer for integrationsindsatsen i Danmark. Danish Ministry of Refugees Immigration and Integration Affairs. https://www.nyidanmark.dk/bibliotek/publikationer/rapporter/2007/taenketanken_vaerdier_og_normer_baggrundsrapport.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2012

Jann B (2006) FAIRLIE: Stata module to generate nonlinear decomposition of binary outcome differentials. IDEAS, Research Division of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. http://ideasrepecorg/c/boc/bocode/s456727html. Accessed 25 Sep 2012

Jann B (2008) OAXACA: Stata module to compute the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. IDEAS, Research Division of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456936.html. Accessed 25 Sep 2012

Kerr SP, Kerr WR (2011) Economic impacts of immigration: a survey. Finn Econ Pap 24:1–32

Liebig T (2007) The labour market integration of immigrants in Denmark. OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers DELSA/ELSA/WD/SEM(2007)5. http://www.oecd.org/els/38195773.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2012

Manning A, Roy S (2010) Culture clash or culture club? The identity and attitudes of immigrants in Britain. Econ J 120:72–100

Nekby L, Rödin M (2010) Acculturation identity and employment among second and middle generation immigrants. J Econ Psychol 31:35–50

Paulhus DL (1991) Measurement and control for response bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS (eds) Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Academic, San Diego, pp 17–59

Rockwool Foundation Research Unit (2011) Etnisk diskrimination: lige børn leger helst. Rockwool Foundation Newsletter June 2011, Copenhagen. http://www.rff.dk/files/RFF-site/Publikations%20upload/Newsletters/Dansk/06.11%20RFF%20Nyhedsbrev%20CS4%20NET.pdf. Accessed 25 Sep 2012

Russo G, van Hooft E (2011) Identities conflicting behavioural norms and the importance of job attributes. J Econ Psychol 32:103–119

Sen A (1977) Rational fools: a critique of the behavioral foundations of economics theory. Philos Public Aff 6:317–344

Sen A (2001) Other people. British Academy lecture. In: The British Academy (ed) 2000 lectures and memoirs, vol 111. Oxbow Books, Oxford

Statistics Denmark (2006) Økonomisk-Politisk Kalendar 2006. Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. http://www.dst.dk/da/statistik/emner/konjunkturindikatorer/okonomisk_politisk.aspx. Accessed 4 Dec 2012

Statistics Denmark (2011) Indvandrere i Danmark 2011. Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. http://www.dst.dk/pukora/epub/upload/16209/indv.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec2012

Statistics Denmark (2012) Database StatBank Denmark, Copenhagen. http://wwwstatbankdk/statbank5a/defaultasp?w=1024. Accessed 3 Aug2012

Zimmermann KF (2007) The economics of migrant ethnicity. J Popul Econ 20:487–494

Acknowledgements

Support from the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation for the funding of this project through a grant provided to the Danish Graduate School for Integration, Production and Welfare is gratefully acknowledged. I am in particular thankful to three anonymous referees, Sylvie Blasco, Herbert Brücker, Anna Piil Damm, Vibeke Jakobsen, Chantal Pohl Nielsen, Giovanni Peri, Dario Pozzoli, Marianne Simonsen, and Lars Skipper for the valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. Special thanks, moreover, go to participants at seminars at Aarhus University and SFI, the NORFACE migration network 2011 conference in London, and the ESRA 4th Conference in Lausanne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gorinas, C. Ethnic identity, majority norms, and the native–immigrant employment gap. J Popul Econ 27, 225–250 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0463-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0463-3