Abstract

This paper empirically analyzes the labor supply effects of two “making work pay” reforms in Germany. We provide evidence in favor of policies that distinguish between low effort and low productivity by targeting individuals with low wages rather than those with low earnings. We discuss our results more generally and with comparisons to the family-based tax credits in force in the US and the UK. For the evaluation of the policies, we apply a static structural labor supply framework and explicitly account for demand-side constraints by using a double-hurdle model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Another difference with the prereform situation is that income up to 400 Euro from a mini-job held as a secondary activity does not cumulate with the primary income for tax purposes, i.e., both activities are taxed independently. This may explain the apparent success of mini-jobs as a “moonlighting” activity, a feature not captured in our analysis. Modelling multiple activities is often difficult, as it requires information not covered by income surveys.

Conditioning on productivity rather than earnings is a practical example of first best taxation but conveys questions about the cost and reliability of measures of wage rates (or working time) by the administration. We assume hereafter that these administrative issues can be solved and do not generate additional costs for the government (in practice, in Belgium, the information is based on the contractual hours declared by the employers to the social security institutions).

As common in the labor supply literature, we do not model the behavior of the self-employed. The working behavior of the self-employed strongly depends on risk-measures, and moreover, working time and gross earnings are difficult to determine.

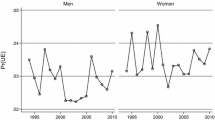

Note that these rates differ from official unemployment statistics since their denominators contain some of the inactive population (precisely the voluntary unemployed) and also because of selection criteria

The underemployment ratio is defined as the relation of the number of unemployed individuals and participants in several active labor market programs to the number of all employed persons plus these programs’ participants. The corrected population density is used to improve the comparability of rural labor office districts with metropolitan and city areas. In addition, the vacancy quota, describing the relation of all reported vacancies at the labor office to the number of employed persons, and the placement quota, which contains the number of placements in relation to the number of employed persons, are used. Finally, an indicator for the tertiarization level built on the number of employed persons in agricultural occupations and an indicator for the seasonal unemployment are considered.

Since the clusters refer to labor office districts and the individuals’ place of residence is on county level, we have to do some readjustments. We follow a rather simplistic approach and assign counties belonging to more than one labor office district to the one where the majority of inhabitants are located.

For this application, we use the German tax-benefit simulation model STSM. For a detailed description, see Steiner et al. (2005)

In the estimation, we account for the problem of matching microdata with aggregate (regional) information as described in Moulton (1990). We allow for correlation within a region and, therefore, derive consistent standard errors for the regional variables.

We follow a calibration method that is consistent with the probabilistic nature of the model at the individual level (Creedy and Duncan 2002). It consists in drawing for each household a set (here, 100 draws) of J + 1 random terms from the EV − I distribution that generates a perfect match between predicted and observed choices. The same draws are kept when predicting labor supply responses to a shock on wages or a tax reform. Averaging individual supply responses over a large number of draws provides robust transition matrices. Confidence intervals for elasticities (or labor supply responses to a reform) are obtained by repetitive random draws of the preference parameters from their estimated distributions and, for each draw, by applying the calibration procedure.

Previous findings confirm that elasticities of hours for single workers are around twice as small when accounting for demand constraints (Euwals and van Soest 1999).

The mini-job reform has, indeed, only a small direct effect on labor cost, while the Employment Bonus has no effect whatsoever on labor demand. In the case of the mini-job, however, firms may adjust labor demand in different ways to respond to changes in legislation (e.g., by splitting previous full-time jobs into several mini-jobs). Other possible feedback effects may lead to changes in the equilibrium gross wages (here assumed to be constant). These effects are very difficult to account for without a more comprehensive framework (e.g., CGE models).

A distinction must be made. The population already employed may freely choose to change working hours or to withdraw from the labor market (they are not rationed). The voluntarily inactive may decide to enter the labor market following the reform, but their expected labor supply is weighted by their individual rationing risk, which is deterministically predicted ex-ante.

With the mini-job reform, for instance, almost 16% of the voluntarily inactive that are induced to enter the labor market will be rationed from the demand side. This percentage is significantly higher than the current unemployment rate of any of the groups. This is hardly surprising, given that the labor market characteristics of the inactive population are often weaker than those of the active population.

Note also that our estimates seem considerably lower than the 523,000 new mini-jobs that have been created between March 2003 and March 2004 according to the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit 2004). However, we focus here on additionally created employment, while the estimates of the FEA include persons who were already employed before the reform (241,000 with an income between 326 and 400 Euro and 196,000 with an income higher than 400 Euro) and who are now categorized as “mini-jobbers.” Official job creations then decrease down to around 86,000. Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that we concentrate on the main labor force, excluding students and pensioners from our analysis. Assuming that these groups account for about a third of the total effect, the FEA number is further reduced down to around 50,000, i.e., a number well within the estimated confidence intervals of both models.

For couples, we estimate one rationing probability per spouse.

We can reasonably assume that desired hours of employed individuals coincide with actual observed hours. This is indeed the case for over 85% of the working population, while means are, respectively, 21.9 and 21.2 h per week (when including nonparticipants). For the involuntarily unemployed, we make use of the information in the data about which type of contract they are looking for, part-time (21–34 h) or full-time (35–40 h) work. This additional information allows us to assign the involuntary unemployed to the respective group and, thus, to estimate the model more precisely. Doing so, we assume that the involuntary unemployed have only a restricted choice set when working.

References

Arntz M, Feil M, Spermann A (2003) Die Arbeitsangebotseffekte der neuen mini- und midijobs - eine ex-ante evaluation, 3/2003. Mittelungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung

Bargain O, Orsini K (2006) In-work policies in Europe: killing two birds with one stone. Labour Econ 13:667–697

Bingley P, Walker I (1997) The labour supply, unemployment and participation of lone mothers in in-work transfer programmes. Econ J 107:1375–1390

Blien U, Hirschenauer F, Arendt M, Braun HJ, Gunst D-M, Kilcioglu S, Kleinschmidt H, Musati M, Ross H, Vollkommer D, Wein J (2004) Typisierung von bezirken der agenturen der arbeit. Z Arb Marktforsch 37(2):146–175

Blundell R (2000) Work incentives and ‘in-work’ benefit reforms: a review. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 18:27–44

Blundell R, Duncan A, McCrae J, Meghir C (2000) The labour market impact of the working families tax credit. Fisc Stud 21(1):75–104

Blundell R, Ham J, Meghir C (1987) Unemployment and female labour supply. Econ J 97:44–64

Blundell R, MaCurdy T (1999) Labor supply: a review of alternative approaches. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3A. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1559–1695

Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2004) Mini- und midijobs in Deutschland. Nürnberg

Creedy J, Duncan A (2002) Behavioural microsimulation with labour supply responses. J Econ Surv 16:1–40

Duncan A, MacCrae J (1999) Household labour supply, childcare costs and in-work benefits: modelling the impact of the working families tax credit in the UK. Working Paper, IFS

Eissa N, Hoynes H (2004) Taxes and the labor market participation of married couples: the earned income tax credit. J Public Econ 88:1931–1958

Euwals R, van Soest A (1999) Desired and actual labour supply of unmarried men and women in the Netherlands. Labour Econ 6:95–118

Haan P (2006) Much ado about nothing: conditional logit vs. random coefficient models for estimating labour supply elasticities. Appl Econ Lett 13:251–256

Haan P, Myck M (2007) Apply with caution: introducing UK-style in-work support in Germany. Fisc Stud 28(1):43–72

Haan P, Steiner V (2005) Distributional effects of the German tax reform 2000—a behavioral microsimulation analysis. J Appl Soc Sci Stud 125:39–49

Ham J (1982) Estimation of a labour supply model with censoring due to unemployment or underemployment. Rev Econ Stud 49:335–354

Hogan V (2004) The welfare cost of taxation in a labor market with unemployment and non-participation. Labor Econ 11:395–413

Laroque G, Salanie B (2002) Labour market institutions and employment in France. J Appl Econ 7:25–48

McFadden D (1974) Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P (ed) Frontiers in econometrics. Academic, New York

Moulton B (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72:334–338

Orsini K (2006) Is Belgium making work pay? CES Discussion Paper, No. 06/06, KU Leuven

Steiner V, Haan P, Wrohlich K (2005) Dokumentation des steuer-transfer-mikrosimulationsmodells 1999–2002. DIW Data Documentation

Steiner V, Wrohlich K (2005) Work incentives and labour supply effects of the mini-jobs reform in Germany. Empirica 32:91–116

van Soest A (1995) Structural models of family labor supply: a discrete choice approach. J Human Resources 30:63–88

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor, Christian Dustmann, and an anonymous referee and Holger Bonin, André Decoster, Friedhelm Pfeiffer, Benjamin Price, Viktor Steiner, and Katharina Wrohlich for valuable comments, as well as contributions from participants of the DIW and IZA seminars. Financial support of the German Science Foundation (DFG) under the research program “Flexibilisierungspotenziale bei heterogenen Arbeitsmärkten” is gratefully acknowledged (project STE 681/5-1). The usual disclaimer applies. A previous version of this paper circulated as “Making Work Pay in a Rationed Labour Market: the Mini-Job Reform in Germany.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Christian Dustmann

A Technical appendix

A Technical appendix

1.1 A.1 Unconstrained model

We assume the error terms ϵ ij of the utility function to be i.i.d. according to an EV-I distribution. Then, the probability that alternative k is chosen by household i is given by McFadden (1974):

Further, we model the utility function in a quadratic specification as in Blundell et al. (2000). Preferences for income and leisure coefficients vary conditional on age, number and age of children, and region of residence. We follow van Soest (1995) and introduce dummy variables for the part-time categories in order to capture specific (dis)utility from working part-time. In the estimation, we do not consider potential effects of unobserved heterogeneity, which implies that the IIA property holds. However, Haan (2006) has shown that labor supply elasticities estimated on the same data as in the present study do not differ significantly when unobserved heterogeneity is introduced.

1.2 A.2 Constrained model

Denoting d as the desired hours and p as a dummy representing nonrationing, we can summarize the situation of a single individual with three possible states,Footnote 15 to be voluntarily inactive, to be rationed, and to participate without being rationed. In the present set-up, these probabilities are written as follows:Footnote 16

As in Duncan and MacCrae (1999), we assume that the error terms of the labor supply model and the probability of rationing are independent, which allows us to estimate the unemployment risk separately. A more general approach could make use of a simulated maximum likelihood to introduce a correlation between these two terms. The assumption of independent error terms implies, in particular, that, conditional on observed characteristics, having positive desired hours is independent on the risk of rationing. In this sense, our specification rules out discouragement effects, which are unobservable. Indeed, we mix those who are “voluntarily” inactive for two different reasons: either due to high fixed cost of work (due to, e.g., childcare costs) or to high search costs (e.g., due to rationing). As mentioned above, the individual unemployment risk is conditioned on the individual employment history and, hence, partly accounts for discouragement effect related to the employment status over the last 3 years (yet the initial state is assumed random). To account for discouragement, this effect could be modeled explicitly (structurally) by introducing job search cost that would increase with the risk of unemployment (cf. Duncan and MacCrae 1999). The sample log-likelihood to be maximized can be derived by summing individuals’ probabilities for their working state, using Eq. 3 for the unconstrained model or Eqs. 4–6 for the constrained model.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bargain, O., Caliendo, M., Haan, P. et al. “Making work pay” in a rationed labor market. J Popul Econ 23, 323–351 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0220-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0220-9