Abstract

Purpose

Fluid overload is a risk factor for poor outcome in intensive care; thus volume loading should be tailored towards patients who are likely to increase stroke volume. We aimed to evaluate the paediatric predictive ability (stroke volume increase of at least 15 % after fluid bolus) of novel and established volumetric and dynamic haemodynamic variables, and assess the influence of baseline contractility on response.

Methods

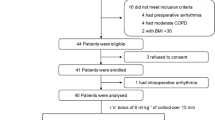

We assessed 142 volume loading episodes (10 ml/kg crystalloid) in 100 critically ill ventilated children, median (interquartile) weight 10 (5.6–15) kg. Eight advanced haemodynamic variables were assessed using two commercially available devices. Systemic ventricular contractility was measured as the maximum rate of systolic arterial pressure rise.

Results

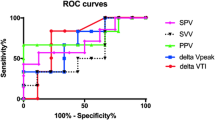

Overall, predictive ability was poor, with volumetric variables performing better than dynamic (area under receiver operating characteristic curves ranged from 0.53 to 0.67). The best predictor was total end-diastolic volume index; however, this did not increase in a consistent way with volume loading, with change post volume being weakly related to baseline values (r = −0.19, p = 0.02). A multivariable model quantified the importance of contractility in stroke volume response. Children with high baseline contractility (≥75th centile) typically achieved a positive stroke volume response when end-diastolic volume values changed by 10–15 ml/m2.6, whereas patients with low contractility (≤25th centile) typically required end-diastolic volume increases of 35–40 ml/m2.6.

Conclusions

Current paediatric predictors of volume response perform poorly; prediction may be improved if baseline contractility is taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Calculated using pooled, weighted data from relevant studies within Gan [5].

References

Marik PE (2009) Techniques for assessment of intravascular volume in critically ill patients. J Intensive Care Med 24:329–337

Valentine SL, Sapru A, Higgerson RA, Spinella PC, Flori HR, Graham DA, Brett M, Convery M, Christie LM, Karamessinis L, Randolph AG, Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigator’s (PALISI) Network, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Research Network (ARDSNet) (2012) Fluid balance in critically ill children with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 40:2883–2889

Willson DF, Thomas NJ, Tamburro R, Truemper E, Truwit J, Conaway M, Traul C, Egan EE, Pediatric Acute Lung and Sepsis Investigators Network (2013) The relationship of fluid administration to outcome in the pediatric calfactant in acute respiratory distress syndrome trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 14:666–672

Sutherland SM, Zappitelli M, Alexander SR, Chua AN, Brophy PD, Bunchman TE, Hackbarth R, Somers MJ, Baum M, Symons JM, Flores FX, Benfield M, Askenazi D, Chand D, Fortenberry JD, Mahan JD, McBryde K, Blowey D, Goldstein SL (2010) Fluid overload and mortality in children receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: the prospective pediatric continuous renal replacement therapy registry. Am J Kidney Dis 55:316–325

Gan H, Cannesson M, Chandler JR, Ansermino JM (2013) Predicting fluid responsiveness in children: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 117:1380–1392

Michard F, Teboul J (2002) Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest 121:2000–2008

Michard F (2005) Changes in arterial pressure during mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology 103:419–428

Monnet X, Teboul JL (2006) Invasive measures of left ventricular preload. Curr Opin Crit Care 12:235–240

Pinsky MR (2015) Understanding preload reserve using functional hemodynamic monitoring. Intensive Care Med 41:1480–1482

Stewart GN (1921) The pulmonary circulation time, the quantity of blood in the lungs and the output. Am J Physiol 58:20–44

Lansdorp B, Lemson J, van Putten MJ, de Keijzer A, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P (2012) Dynamic indices do not predict volume responsiveness in routine clinical practice. Br J Anaesth 108:395–401

de Waal EE, Rex S, Kruitwagen CL, Kalkman CJ, Buhre WF (2009) Dynamic preload indicators fail to predict fluid responsiveness in open-chest conditions. Crit Care Med 37:510–515

Rex S, Schälte G, Schroth S, de Waal EE, Metzelder S, Overbeck Y, Rossaint R, Buhre W (2007) Limitations of arterial pulse pressure variation and left ventricular stroke volume variation in estimating cardiac pre-load during open heart surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 51:1258–1267

Funk DJ, Jacobsohn E, Kumar A (2013) Role of the venous return in critical illness and shock: part II-shock and mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 41:573–579

Lansdorp B, Hofhuizen C, van Lavieren M, van Swieten H, Lemson J, van Putten MJ, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P (2014) Mechanical ventilation-induced intrathoracic pressure distribution and heart–lung interactions. Crit Care Med 42:1983–1990

Kronas N, Kubitz JC, Forkl S, Kemming GI, Goetz AE, Reuter DA (2011) Functional hemodynamic parameters do not reflect volume responsiveness in the immediate phase after acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 25:780–783

Reuter DA, Kirchner A, Felbinger TW, Weis FC, Kilger E, Lamm P, Goetz AE (2003) Usefulness of left ventricular stroke volume variation to assess fluid responsiveness in patients with reduced cardiac function. Crit Care Med 31:1399–1404

Krivitski NM, Kislukhin VV, Thuramalla NV (2008) Theory and in vitro validation of a new extracorporeal arteriovenous loop approach for hemodynamic assessment in pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 9:423–428

Romano SM, Pistolesi M (2002) Assessment of cardiac output from systemic arterial pressure in humans. Crit Care Med 30:1834–1841

Masutani S, Iwamoto Y, Ishido H, Senzaki H (2009) Relationship of maximum rate of pressure rise between aorta and left ventricle in pediatric patients. Implication for ventricular-vascular interaction with the potential for noninvasive determination of left ventricular contractility. Circ J 73:1698–1704

Segers P, Stergiopulos N, Westerhof N (2002) Relation of effective arterial elastance to arterial system properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H1041–H1046

Lytrivi ID, Bhatla P, Ko HH, Yau J, Geiger MK, Walsh R, Parness IA, Srivastava S, Nielsen JC (2011) Normal values for left ventricular volume in infants and young children by the echocardiographic subxiphoid five-sixth area by length (bullet) method. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 24:214–218

Buechel EV, Kaiser T, Jackson C, Schmitz A, Kellenberger CJ (2009) Normal right- and left ventricular volumes and myocardial mass in children measured by steady state free precession cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 11:19

Saxena R, Durward A, Puppala NK, Murdoch IA, Tibby SM (2013) Pressure recording analytical method for measuring cardiac output in critically ill children: a validation study. Br J Anaesth 110:425–431

Saxena R, Krivitski N, Peacock K, Durward A, Simpson JM, Tibby SM (2015) Accuracy of the transpulmonary ultrasound dilution method for detection of small anatomic shunts. J Clin Monit Comput 29(3):407–414

Biais M, Cottenceau V, Stecken L, Jean M, Ottolenghi L, Roullet S, Quinart A, Sztark F (2012) Evaluation of stroke volume variations obtained with the pressure recording analytic method. Crit Care Med 40:1186–1191

Marik PE, Cavallazzi R, Vasu T, Hirani A (2009) Dynamic changes in arterial waveform derived variables and fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 37:2642–2647

Zhang Z, Lu B, Sheng X, Jin N (2011) Accuracy of stroke volume variation in predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anesth 25:904–916

Senzaki H, Akagi M, Hishi T, Ishizawa A, Yanagisawa M, Masutani S et al (2002) Age associated changes in arterial elastic properties in children. Eur J Pediatr 161:547–551

Sharp MK, Pantalos GM, Minich L, Tani LY, McGough EC, Hawkins JA (2000) Aortic input impedance in infants and children. J Appl Physiol 88:2227–2239

Roach MR, Burton AC (1959) The effect of age on the elasticity of human iliac arteries. Can J Biochem Physiol 37:557–570

Senzaki H, Chen CH, Masutani S, Taketazu M, Kobayashi J, Kobayashi T, Sasaki N, Asano H, Kyo S, Yokote Y (2001) Assessment of cardiovascular dynamics by pressure–area relations in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 122:535–547

Michard F, Alaya S, Zarka V, Bahloul M, Richard C, Teboul JL (2003) Global end-diastolic volume as an indicator of cardiac preload in patients with septic shock. Chest 124:1900–1908

Vigani A, Shih A, Queiroz P, Pariaut R, Gabrielli A, Thuramalla N, Bandt C (2012) Quantitative response of volumetric variables measured by a new ultrasound dilution method in a juvenile model of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Resuscitation 83:1031–1037

Klitsie LM, Hazekamp MG, Roest AA, Van der Hulst AE, Gesink-van der Veer BJ, Kuipers IM, Blom NA, Ten Harkel AD (2013) Tissue Doppler imaging detects impaired biventricular performance shortly after congenital heart defect surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 34:630–638

Raj S, Killinger JS, Gonzalez JA, Lopez L (2014) Myocardial dysfunction in pediatric septic shock. J Pediatr 164:72–77

Geerts BF, Maas JJ, Aarts LP, Pinsky MR, Jansen JR (2010) Partitioning the resistances along the vascular tree: effects of dobutamine and hypovolemia in piglets with an intact circulation. J Clin Monit Comput 24:377–384

Scott-Douglas NW, Robinson VJB, Smiseth OA, Wright CI, Manyari DE, Smith ER, Tyberg JV (2002) Effects of acute blood volume changes on intestinal vascular capacitance: a mechanism whereby capacitance regulates cardiac output. Can J Cardiol 18:515–522

Macé L, Dervanian P, Bourriez A, Mazmanian GM, Lambert V, Losay J, Neveux JY (2000) Changes in venous return parameters associated with univentricular Fontan circulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279:H2335–H2343

de la Oliva P, Menéndez-Suso JJ, Iglesias-Bouzas M, Álvarez-Rojas E, González-Gómez JM, Roselló P, Sánchez-Díaz JI, Jaraba S, Spanish Group for Preload Responsiveness Assessment in Children (2015) Cardiac preload responsiveness in children with cardiovascular dysfunction or dilated cardiomyopathy: a multicenter observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 16:45–53

Trof RJ, Danad I, Reilingh MW, Breukers RM, Groeneveld AB (2011) Cardiac filling volumes versus pressures for predicting fluid responsiveness after cardiovascular surgery: the role of systolic cardiac function. Crit Care 15:R73

Bagshaw SM, Cruz DN (2010) Fluid overload as a biomarker of heart failure and acute kidney injury. Contrib Nephrol 164:54–68

McLuckie A, Bihari D (2000) Investigating the relationship between intrathoracic blood volume index and cardiac index. Intensive Care Med 26:1376–1378

Buhre W, Kazmaier S, Sonntag H, Weyland A (2001) Changes in cardiac output and intrathoracic blood volume: a mathematical coupling of data? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 45:863–867

Durand P, Chevret L, Essouri S, Haas V, Devictor D (2008) Respiratory variations in aortic blood flow predict fluid responsiveness in ventilated children. Intensive Care Med 34:888–894

Scolletta S, Bodson L, Donadello K, Taccone FS, Devigili A, Vincent JL, De Backer D (2013) Assessment of left ventricular function by pulse wave analysis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 39:1025–1033

De Hert SG, Robert D, Cromheecke S, Michard F, Nijs J, Rodrigus IE (2006) Evaluation of left ventricular function in anesthetized patients using femoral artery dP/dt(max). J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 20:325–330

Maas JJ, Geerts BF, van den Berg PC, Pinsky MR, Jansen JR (2009) Assessment of venous return curve and mean systemic filling pressure in postoperative cardiac surgery patients. Crit Care Med 37:912–918

Cecconi M, Hofer C, Teboul JL et al (2015) Fluid challenges in intensive care: the FENICE study. Intensive Care Med 41:1529–1537

Acknowledgments

The manufacturers of the advanced haemodynamic monitors used in this study (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, New York and Vytech, Padova, Italy) provided hardware and consumables free of charge. Rohit Saxena received an educational grant from Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY to partially cover his student fees with Kings College London. The current work forms part of his submission for the research degree MDres (Doctor of Medicine: Research).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared for any author.

Additional information

Take-home message: The majority of advanced haemodynamic variables (volumetric and dynamic) have poor to moderate predictive ability in children in terms of the stroke volume response to fluid boluses. Baseline contractility is an important factor influencing patients’ response to fluid volume loading, such that a patient with poor baseline contractility will need to increase their end-diastolic volume by an increment that is 3–4 times greater than that of a patient with good contractility to be able to increase stroke volume by more than 15 %.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saxena, R., Durward, A., Steeley, S. et al. Predicting fluid responsiveness in 100 critically ill children: the effect of baseline contractility. Intensive Care Med 41, 2161–2169 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-4075-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-4075-8