Abstract

Objectives

The risk of suicidal behavior after discharge from psychiatric admission is high. The aim of this study was to examine whether the SAFE intervention, an implementation of a systematic safer discharge procedure, was associated with a reduction in suicidal behavior after discharge.

Methods

The SAFE intervention was implemented at Mental Health Center Copenhagen in March 2018 and consisted of three systematic discharge procedures: (1) A face-to-face meeting between patient and outpatient staff prior to discharge, (2) A face-to-face meeting within the first week after discharge, and (3) Involvement of relatives. Risk of suicide attempt at six-month post-discharge among patients discharged from the SAFE intervention was compared with patients discharged from comparison mental health centers using propensity score matching.

Results

7604 discharges took place at the intervention site, which were 1:1 matched with discharges from comparison sites. During the six months of follow-up, a total of 570 suicide attempts and 25 suicides occurred. The rate of suicide attempt was 11,652 per 100,000 person-years at the SAFE site, while it was 10,530 at comparisons sites. No observable difference in suicide attempt 1.10 (95% CI: 0.89–1.35) or death by suicide (OR = 1.27; 95% CI:0.58–2.81) was found between sites at 6-month follow-up.

Conclusion

No difference in suicidal behavior between the sites was found in this pragmatic study. High rates of suicidal behavior were found during the 6-months discharge period, which could suggest that a preventive intervention should include support over a longer post-discharge period than the one-week follow-up offered in the SAFE intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well established that the period shortly after discharge from psychiatric inpatient facilities is associated with a high risk of suicide [1,2,3,4,5]. Regardless of psychiatric diagnoses, the suicide rate during first week after discharge is more than 100-fold higher than the rate for individuals who have not been admitted to psychiatric hospital [3]. Thus, as part of standard care at psychiatric wards in Denmark, a suicide risk assessment is generally conducted at the time of discharge to determine whether it is safe to send the patient home. Although most people are considered not at acute risk of suicide at the time of discharge [6], it may be challenging to account for non-clinical factors, such as the home environment and current living conditions of the patient, when arriving home [7]. Many people who are hospitalized for psychiatric disorders in Denmark face challenging situations, as 18% are without a job, 23% on disability pensions and 16% have previously received treatment for alcohol- or substance misuse [8]. It is, therefore, not unlikely that patients may encounter stressful and chaotic situations when being discharged, which potentially could trigger suicidal thoughts and behaviors. These may be further exacerbated through low support from the social network. The Danish Health Data Authority reports that the average number days per psychiatric admission has declined from 24.3 days per admission in 2010 to 19.2 in 2017. Shorter admission times could imply a higher pressure for discharging too soon to make room for new patients; consequently, some patients may not be considered fully recovered at the time of discharge, thus, emphasizing the importance of attendance in continued care in outpatient settings.

In meta-analyses, brief suicide interventions offered during high-risk periods, such as time of discharge, have been linked to a 30–40% reductions in suicidal behavior (i.e., suicide attempt and suicide) [9, 10]. Thus, a safety plan consisting of strategies on how to manage crisis, for instance, trying to distract oneself from suicide thoughts and removing access to lethal objects, such as medicine or guns has been suggested as a promising tool for people at risk of suicide [9, 10]. In addition, other brief interventions, such as follow-up contact after discharge (by telephone, mail, text, postcard) and care coordination (planning follow-up contact with psychiatric services) have been associated with reductions. Most of these follow-up interventions were not provided face-to-face, but instead over the phone or in a text format. A face-to-face meeting between the patient and the healthcare provider from the outpatient clinic prior to discharge was linked to a higher compliance with continuation of treatment after discharge [11,12,13], which is a promising feature because discontinuation of treatment has been linked to suicidal behavior [14, 15]. For this reason, it is plausible that a face-to-face meeting might prevent suicidal behavior. Ideally, a such meeting should be conducted in in the patient’s home, as this may give the health care provider an opportunity to assess the patient’s recovery and social situation after discharge, in addition, to reducing likelihood of a ‘no show’. The SAFE intervention consisted of a face-to-face meeting in first week after discharge and was designed to ensure a continued care during the transitioning from being admitted to living at home. The goal of the SAFE intervention was to identify and prevent suicidal behavior during the critical post-discharge phase.

The aim of this study was to examine whether patients who were discharged from the SAFE-intervention site had lower risks of suicide attempt and suicide than a propensity-matched comparison group of patients discharged from control sites when assessed six months after discharge.

Methods

Study design, setting, and data sources

We applied a quasi-experimental design where individuals discharged from one mental health center (MHC) were offered the SAFE intervention and compared to a propensity-score-matched sample of individuals discharged from other MHCs in the same region. The study may be considered as a natural experiment because individuals were included into the study if they lived in the catchment areas of the studied MHCs. The catchment area consisted of eight MHCs within the Capital Region of Denmark. Each center served as a defined catchment area. The SAFE intervention was implemented at MHC Copenhagen, while four adjacent MHCs, MHC Ballerup, MHC Glostrup, MHC Amager, and MHC North Zealand, were used for the comparison. The three other MHCs in the Capital Region of Denmark were excluded from the study; MHC Bornholm, which was situated on an island two hours from Copenhagen city with a different population and level of urbanicity; Psychotherapeutic Center Stolpegård, which exclusively provided outpatient treatment; and MHC Sct. Hans, which was a specialized center for treatment of forensic patients and patients with dual diagnosis. The SAFE project was implemented from March 1, 2018 to March 31, 2020. Information on individuals discharged from the included psychiatric hospitals was obtained from national hospital registers, in which all in-, out-, and emergency department patients seen at psychiatric hospitals in Denmark since 1995, have been recorded. Individual-level data on discharges prior to 2. February 2019 were obtained from the Danish Psychiatric Research Register [16]. After this date, data on all discharges were derived from the National Patient Register. Each hospital in Denmark has an id number, and this id number was used to identify inpatients discharged from each of the five MHCs [17]. Psychiatric diagnoses were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, version 10 (ICD-10) [18].

Participants

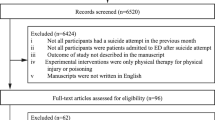

We obtained data on all patients, aged 18 or above, discharged from one of the five MHCs. Each discharge was considered as a separate unit of follow-up, i.e., if a patient was admitted to psychiatric hospital several times during the follow-up, each discharge would be analyzed separately in the study. Patients were excluded if they had been recorded with primary diagnoses of one of the following disorders: organic psychiatric disorders (ICD-10: F00–F09), eating disorders (ICD-10: F50–F59), mental retardation (ICD-10: F70–F79), pervasive and specific developmental disorders (ICD-10: F80–F89), and behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (ICD-10: F90–F98). Individuals with these disorders (n = 361) were excluded because they attended specialized outpatient treatment.

Intervention

The SAFE intervention consisted of the following three components, which were systematically implemented: (1) Face-to-face introduction to SAFE prior discharge where eligible inpatients at the intervention site were invited to participate in the project during a personal meeting with a health care provider from the outpatient clinic, while still being in admission. During this first meeting, the health care provider from the outpatient clinic interviewed the patient regarding their home environment and together they complied a safety plan as well as scheduled a face-to-face meeting for first week after discharge. The health care providers professional backgrounds were social workers, nurses, occupational therapist or psychologists.; (2) A face-to-face meeting during the first week after discharge was held between patient and, ideally, the same health care provider, which they met at the hospital ward. The meeting was preferably conducted as a home visit, but patients could also request to meet in different venue, for instance, the outpatient clinic or at café. The home visit allowed the clinician to assess the patients’ post-discharge situation, i.e., identify possible stressors, monitor the plans for follow-up, review the safety plan, and reassess the suicide risk as well as inform the patient about suicide warning signs; and (3) Involvement of relatives where patients were encouraged to involve relatives in their treatment course as relatives can provide emotional and practical support to the patient in a vulnerable situation. If involved, the health care provider would inform the relatives on suicide warning signs, as this might foster faster help-seeking if the patient’s condition should deteriorate.

The SAFE intervention was compared with treatment-as-usual offered at the comparison sites, which depending on severity of condition and disorder consisted of reference to a variety of services. These services could be referral to a private psychiatrist, substance abuse treatment, psychotherapy or follow-up care in secondary health care and the availability of appointments to these services are often several weeks due to waitlists. Also, some were referred at discharge to contact their general practitioner when at home. The overall difference to the intervention was that in SAFE, everyone, no matter of condition or disorder, was systematically offered to receive a face-to-face follow-up in the week after discharge where the risk of suicide is really high whereas in treatment-as-usual many did not have a follow-up due to waitlist problems.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were suicide and suicide attempt, respectively. Suicide deaths were identified in the Cause of Death Register as one of the following ICD-10 codes: X60–X84 or Y87.0 [19].

Suicide attempt was defined as a presentation to either psychiatric or somatic hospitals, including emergency departments where a suicide attempt had been recorded using the following ICD-10 codes X60–X84 or when reason for contact was indicated as suicide attempt in both The National Patient Register and The Danish Psychiatric Research Register. In addition, the following combinations of ICD diagnoses were included as hospital contacts due to suicide attempt: a main diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-10: F00–F99) together with one of the following sub-diagnoses: S51, S55, S59, S61, S65, S69 (cutting by sharp objects), T36–T50 (poisoning by pharmaceuticals), T52–T60 (poisoning by non-pharmaceuticals) as well as all admissions with a main diagnosis of T39, T40 (poisoning by mild analgesics; except T40.1), T42, T43, and T58 (poisoning by opioids, psychotropics, and by carbon monoxide).

Follow-up

Participants were followed from date of discharge until episode onset of the studied outcome, new psychiatric admission, death, emigration or six months post-discharge, which ever occurred first.

Power calculation

Based on estimates on previous population attributable risk calculations [20], approximately 40 suicidal acts in the first week after discharge and approximately 200 in the first 6 months after discharge were expected. With approximately 6000 discharges, our power calculation (based on a statistical significance level of 5 percent and a power of 90 percent) shows that we have the power to find a difference in suicidal acts of 7% versus 5% between the control and SAFE sites, corresponding to a 28 percent reduction in suicidal behavior.

Statistical analysis

Individuals discharged from the SAFE intervention site were matched to individuals from the comparison group using exact matching and a propensity score. The unit for the matching was discharges not individuals, hence, if an individual was discharged more than once from the intervention site then a matching was conducted for each discharge. The propensity score was derived from following socio-demographics and health-related variables from nationwide registers: sex (male, female); age group (18–29 years, 30–44 years, 45–64 years, 65 + years); socio-economic status (working, unemployed/social or sickness benefit, retired, missing); highest achieved educational level (elementary school, vocational training, high school, bachelor degree or higher, missing); civil status (married, divorced, never married, missing or other); placed in foster care; primary diagnoses of substance misuse (ICD-10: F10–F19), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD-10: F20–F29), affective disorders (ICD-10: F30–F39), anxiety or stress-related disorders (ICD-10: F40–F49) or personality disorders (ICD-10: F60–F69); admission lasted more than 7 days; ever diagnosed with substance misuse; ever diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis; ever diagnosed with affective disorders; previous suicide attempt; prescribed antipsychotic medication within 12 months of being discharged; prescribed antidepressant medication within 12 months of being discharged; parents with history of psychiatric disorder; and parents with history of a suicide attempt or suicide. Date of discharge was used as time point for the matching and all matching factors were measured on this date. Matching factors were selected because they were considered as predictors of suicidal behavior or factors, which might have described differences between the intervention and comparison groups. An exact matching was prioritized for previous suicide attempt and prescribed antidepressant medication within 12 months of being discharged and a propensity score was calculated for the remaining variables. After having identified a matched comparison group with a 1:1 ratio, odds ratios (OR) of suicide and suicide attempt were calculated in separate models with their 95% confidence intervals at 2 weeks, 1 months and 6 months after discharge. We accounted for multiple discharges of the same individual through adjustments for repeated subjects in the statistical models. Following sensitivity analyses were conducted: Firstly, the first months of the SAFE intervention (from March 1, 2018 to August 31, 2018) were omitted, implying that only discharges after September 1, 2018 onwards were included, to ensure a higher level of adherence to the SAFE intervention, as it might have taken time to implement new procedures into clinical practice. Second, we excluded all patients discharged with a main diagnosis of depression or bipolar disorder, as members of this group were enrolled in a congruent research project during half of the follow-up and, thus, precluded from participating in the SAFE intervention. Third, individuals were censored after a first recorded suicide attempt to test that the risk estimate for suicide attempt in the primary analyses would not be biased by individuals with multiple suicide attempts.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and the cut-off for statistical significance level was set at p = 0.05.

Results

In all, 30,031 discharges of 13,958 individuals occurred between March 1, 2018 and March 31, 2020 at the five MHCs in the Capital Region of Denmark. Of these, 7604 (25%) discharges of 3740 (27%) individuals were from MHC Copenhagen, where the SAFE intervention was implemented, while the remaining 22,427 (75%) discharges of 10,218 (73%) individuals occurred at the four other MHCs (Table 1).

When matching discharges from the SAFE intervention site with discharges from the comparison sites using the propensity score, the range of the percentual differences across the matched factors was reduced from 0.1%–8.0% to 0.0%–2.1%. After the 1:1 matching, the sample consisted of 15,208 discharges, which were followed for up to six months. During follow-up, 570 suicide attempts were recorded. Of these, 298 suicide attempts were by patients from the SAFE intervention site; corresponding to a rate of 11,652 (95% CI: 10,329–12,975) per 100,000 person-years (Table 2). Among the matched comparisons, a total of 272 suicide attempts were observed, resulting in a rate of 10,530 (95% CI: 9279–11,782) per 100,000 person-years. Out of 25 suicide deaths, 14 occurred among patients from the SAFE intervention site, corresponding to a rate of 538 (95% CI: 256–820) per 100,000 person-years, whereas 11 suicides and a rate of 420 (95% CI: 172–668) was found among comparisons over the 6-month follow-up.

We found no statistically significant difference between individuals discharged from the intervention site and the comparison sites with respect to suicide attempt at 2 weeks of follow-up (OR = 1.23; 95% CI: 0.89–1.71). The same applied after 1 month (OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 0.93–1.65) and 6 months of follow-up (OR = 1.10; 95% CI: 0.89–1.35). There was also no observable difference with respect to death by suicide between individuals discharged from the SAFE intervention site and their matched comparisons with an OR of 1.27 (95% CI:0.58–2.81) at 6 months of follow-up. None of sensitivity analyses revealed significant differences in outcomes between those discharged from the intervention and comparison sites (Table 3 and eTable 1).

Discussion

High rates of both suicide attempt (> 10,000 per 100,000 person-years) and suicide (> 400 per 100,000 person-years) were found among patients discharged from psychiatric admission during the follow-up of this brief intervention study. However, our results indicated no observable differences in these rates when comparing patients discharged from the intervention site with those discharged from the comparison sites.

Conflicting effects have been reported for brief suicide interventions targeting critical high-risk periods. While some interventions resulted in statistically significantly reduced risk of suicide attempt [21,22,23,24,25,26], others did not find this [27,28,29,30]. Most of the previously conducted interventions included same elements as examined here, such as interview before discharge with a focus on suicide warning signs and safety planning as well as follow-up contact after discharge (either by phone or post cards). Except for two interventions [23, 24], most have been conducted as randomized controlled trials (RCT) [21, 22, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. All RCTs had small sample sizes and, consequently, only few events of suicide attempt were observed during follow-up; implying that they might not have been sufficiently powered to detect a statistical difference. The two studies, which did not include a randomized allocation, were cohort studies of larger samples (n = 1376[23] and n = 1640[24]) and both identified an effect of the brief intervention over treatment-as-usual (TAU). This is further supported by the findings from two meta-analyses [9, 10] in which these studies were both included. Our study sample was substantially larger (n = 15,208) and we, consequently, observed a large number of events. Still, we did not find that the SAFE intervention was linked to a reduction in risks of suicide attempt and suicide. One reason for this might be differences in study populations; the SAFE intervention was offered to all discharged inpatients whether they had suicidal tendencies or not, while participants in the other studies either experienced current suicidal ideations or had recently presented with a suicide attempt.[21, 22, 24,25,26]. Targeting all patients, as we did may dilute the effectiveness of the intervention, however we choose to offer the intervention to all discharged patients because we know from previous studies that only focusing on those who already had displayed suicidality, we risk bypassing many who will be at suicidal risk after discharge [32]. It is also possible that the SAFE intervention, as a consequence of the pragmatic design, was not offered as stringently as in RCT studies. Due to a new registration system, which was implemented at the MHCs during the follow-up, it was not feasible to register who and how many individuals were offered and/or consented to participate in the SAFE intervention. In other words, we could not assess the fidelity of the study. Still, an internal quality assessment, based on journal audits, suggested a high compliance. During the first months of the SAFE intervention, i.e., March–October 2018, the number of discharged patients who received a face-to-face meeting within 7 days rose from 28 to 77%. Also, the number of recorded suicide risk screenings conducted during the first week after discharge rose from 3 to 19%. During the follow-up, outpatient clinics at control sites initiated competitive efforts, in form of the Flexible Assertive Community Teams (F-ACT) [33] and Acute Teams. These efforts consisted of community outreach for individuals with severe mental illnesses, provided through clinical outpatient teams and, which were offered in the critical post-discharge phase. This may have biased our evaluation as these efforts could be viewed as comparable to the one of the SAFE procedures, namely home-visits during first week after discharge.

Irrespective of a significant effect, there remains a strong rationale for providing the three procedures of the SAFE intervention in clinical practice. Recently, F-ACT have proved to increase the number of outreach visits after discharge as well as outpatient contact with relatives of patients [33], which as mentioned in the introduction may be linked to lower suicide risk. Based on existing evidence, it is possible that these initiatives are most effective when offered to patients who recently suffered from suicidal ideations or behaviors as opposed to offering to all discharged patients, although only focusing on those who presented with suicide attempt/severe suicidal thoughts we risk bypassing offering follow-up help to individuals who become suicidal after discharge.

Strengths and limitation

Besides not being designed as an RCT, not having individual-level information on who received the SAFE intervention, and a lack of fidelity measures, other limitations include (1) the fact that suicide attempts may be underreported as only hospital-recorded incidents were captured, (2) ascertainment bias if those discharged from the SAFE intervention site due to higher expose of safety planning may increase the likelihood that that these individuals sought hospital care for suicide attempt, and (3) the propensity scores only adjusted for observed confounder, not unobserved confounders. A strength of our study is that we had a national coverage of the studied outcomes and no loss to follow-up due to being based on register data.

Conclusion

The high rates of suicide attempt and suicide at the time of discharge underscore the need for suicide preventive efforts. Also, six months after being discharged, high rates of suicidal behavior were found, which suggests that a support may be needed over a longer period of time after discharge than what was offered in the SAFE intervention. We found no effect on suicidal behavior of the SAFE intervention, and it is possible that this null finding can partly be explained by difficulties with implementing SAFE procedures fully in the intervention sites, and by the comparison sites implementing some of the SAFE procedures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark. Data access requires the completion of a detailed application form from the Danish Data Protection Agency, the Danish National Board of Health and Statistics Denmark. For more information on accessing the data, see https://www.dst.dk/en.

References

Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-pavlovic D et al (2017) Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat 74:694–702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044

Chung D, Hadzi-pavlovic D, Wang M et al (2019) Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883

Madsen T, Erlangsen A, Hjorthøj C, Nordentoft M (2020) High suicide rates during psychiatric inpatient stay and shortly after discharge. Acta Psychiatr Scand. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13221

Qin P, Nordentoft M, Hoyer EH et al (2006) Trends in suicide risk associated with hospitalized psychiatric illness: a case-control study based on danish longitudinal registers. J Clin Psychiatry 67:1936–1941

Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S et al (2016) Short-term suicide risk following psychiatric hospital discharge. JAMA Psychiat 73:1119–1126

Madsen T, Egilsdottir E, Damgaard C et al (2021) Assessment of suicide risks during the first week immediately after discharge from psychiatric inpatient facility. Front Psychiatry 12:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643303

Nordentoft M, Erlangsen A, Madsen T (2016) Postdischarge suicides nightmare and disgrace. JAMA Psychiat 73:1113–1114. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2035

Madsen T, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M (2012) Predictors of psychiatric inpatient suicide—a national prospective register-based study. J Clin Psychiatry 73:144–151

Nuij C, van Ballegooijen W, de Beurs D et al (2021) Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention META Analysis.pdf. Br J Psychiatry 219:419–426

Doupnik SK, Rudd B, Schmutte T et al (2020) Association of suicide prevention interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat 19146:1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1586

Riblet N, Shiner B, Scott R et al (2019) Exploring psychiatric inpatients ’ beliefs about the role of post-discharge follow-up care in suicide prevention. Mil Med 184:e91–e100. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy129

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK et al (2003) Continuity of care : a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 327:1219–1221

Olfson M, Mechanic D, Boyer CA, Hansell S (1998) Linking inpatients with schizophrenia to outpatient care. Psychiatr Serv 49:911–917

Choi Y, Nam CMO, Lee SGYU et al (2020) Association of continuity of care with readmission, mortality and suicide after hospital. Int J Qual Heal Care 32:569–576. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa093

Hunt IM, Kapur N, Webb R et al (2009) Suicide in recently discharged psychiatric patients: a case-control study. Psychol Med 39(3):443–449

Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB (2011) The danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health 39:54–57

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 39:30–33

Organization WH (1992) International statistical classification of diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Helweg-Larsen K (2011) The danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health 39:26–29

Qin P, Nordentoft M (2005) Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:427–432

Bryan CJ, Mintz J, Clemans TA et al (2017) Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in U. S. army soldiers : a randomized clinical trial ☆. J Affect Disord 212:64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.028

Comtois KA, Kerbrat AH, Decou CR et al (2019) Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat 76:474–483. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4530

Miller IW Jr, CAC, Arias SA, et al (2017) Suicide prevention in an emergency department population the ED-SAFE study. JAMA Psychiat 2906:563–570. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0678

Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA et al (2018) Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiat 75:894–900. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776

Gysin-maillart A, Schwab S, Soravia L et al (2016) A Novel brief therapy for patients who attempt suicide : a 24-months follow-up randomized controlled study of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP). PLoS Med 13:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001968

Wang Y-C, Hsieh L-Y, Wang M-Y, Chou C-H, Huang M-W, Huei-Chen Ko P (2016) Coping card usage can further reduce suicide reattempt in suicide attempter case management within 3-month intervention. Suicide Life Threat Behav 46:106–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12177

Asarnow JR, Baraff L, Berk M, Grob C, Devich-Navarro M, Suddath R, Piacentini J, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Cohen D, Tang L (2012) Effects of an emergency department mental health intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 62:1303–1309

Grupp-phelan J, Stevens J, Boyd S et al (2019) Effect of a motivational interviewing-based intervention on initiation of mental health treatment and mental health after an emergency department visit among suicidal adolescents a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17941

O’Connor SS, Mcclay MM, Choudhry S et al (2020) Pilot randomized clinical trial of the teachable moment brief intervention for hospitalized suicide attempt survivors ☆. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 63:111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.08.001

Chen W, Ho C, Shyu S et al (2013) Employing crisis postcards with case management in Kaohsiung, Taiwan : 6-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry 13:1–7

Burgess P, Pirkis J, Morton J, Croke E (2000) Lessons from a comprehensive clinical audit of users of psychiatric services who committed suicide. PsychiatrServ 51:1555–1560

Large MM, Ryan CJ (2014) Suicide risk categorisation of psychiatric inpatients: what it might mean and why it is of no use. Australas Psychiatry 22:390–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856214537128

Nielsen CM, Hjorthøj C, Killaspy H, Nordentoft M (2021) Articles The effect of flexible assertive community treatment in Denmark : a quasi-experimental controlled study. Lancet Psychiatry 8:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30424-7

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Library, Copenhagen University Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Trine Madsen (TM) and Annette Erlangsen(AE) and Merete Nordentoft(TM) designed the epidemiological study, Eybjørg Egillsdottir (EE) was project leader on the SAFE intervention, TM and AE carried out analyses, PKA gave statistical support for analyses and TM wrothe main manuscript text and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Madsen, T., Erlangsen, A., Egilsdottir, E. et al. The effect of the SAFE intervention on post-discharge suicidal behavior: a quasi-experimental study using propensity score matching. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02585-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02585-y