Abstract

Purpose

It is unclear how the evidence from clinical trials best translates into complex clinical settings. The aim of this quality improvement (QI) project was to change prescribing practice for rapid tranquillization in inpatient mental health care services examining the effectiveness of the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method.

Methods

A prospective QI project was conducted to ensure that intramuscular (IM) diazepam was substituted with IM lorazepam for benzodiazepine rapid tranquillization in inpatient mental health care. We monitored the prescription and administration of medication for rapid tranquillization before (N = 371), during (N = 1130) and after (N = 364) the QI intervention. Seven iterative PDSA cycles with a multiple-component intervention approach were conducted to gradually turn the prescribing practice in the desired direction. Simultaneously, a standard monitoring regimen was introduced to ensure patient safety.

Results

Lorazepam administrations gradually replaced diazepam during the intervention period which was sustained post-intervention where lorazepam comprised 96% of benzodiazepine administrations for rapid tranquillization. The mean dose of benzodiazepine administered remained stable from pre (14.40 mg diazepam equivalents) to post (14.61 mg) intervention phase. Close to full compliance (> 80%) with vital signs monitoring was achieved by the end of the observation period.

Conclusion

It was possible to increase the quality of treatment of acute agitation in a large inpatient mental health care setting using a stepwise approach based on iterative PDSA cycles and continuous data feedback. This approach might be valuable in other prescribing practice scenarios with feedback from local stakeholders and opinion leaders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The clinical need for acute tranquillization in inpatient mental health care and which medication to recommend have been the subject of numerous clinical trials. Reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that antipsychotics and benzodiazepines are largely equivalent in terms of efficacy measured as sedation, amelioration of aggression, self-harm or injury to others, and general functioning [1, 2]. Depending on clinical circumstances, either an antipsychotic or a benzodiazepine is preferred. Oral medication is the first choice for acute agitation, but intramuscular (IM) administration is necessary if the patient does not accept oral medication, or if urgent relief or sedation is needed. When benzodiazepines are preferred (e.g., non-psychotic agitation or antipsychotic-naïve patient with psychosis), lorazepam is the internationally recommended drug for IM use in several treatment guidelines [3,4,5] owing to its good absorption and efficacy, relatively short time to action, benign safety profile with few adverse events, and short elimination half-life.

Lorazepam injection solution was not available as a registered drug in Denmark when the project was initiated. Instead, diazepam injection emulsion was the drug of choice for parenteral use when a benzodiazepine was required, despite diazepam emulsion being considered less suitable for IM use in international guidelines due to unreliable and poor absorption [4]. Consequently, there was a clear clinical need to introduce lorazepam injection solution as part of routine clinical practice in Denmark. The process of changing physicians’ prescribing practices is relevant from an international perspective because it is a ubiquitous clinical challenge encountered in many settings. Especially in complex clinical settings there is insufficient knowledge regarding the efficiency of different methods for implementing changes in clinical practice [6, 7]. To build an evidence base for improvement as a science, it is necessary that efforts of development, evaluation and dissemination of quality improvement methods are documented and reported [8].

Accordingly, this quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed to change physicians’ prescribing preference for acute agitation from diazepam to lorazepam for IM use by working through successive Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles characterized by key features previously suggested: an iterative cyclic method, continuous data collection, small-scale testing, and explicit description of the theoretical rationale of the project [9, 10]. This report describes the process and outcomes of the quality improvement project.

Methods

Context

Our institution is a large psychiatric hospital in Denmark, each year treating 52,000 patients with mental illness. The service comprises eight adult psychiatric centres, one centre for children and adolescents, and a shared administration to ensure coordination and quality of development across the hospital.

When introducing IM lorazepam in clinical practice, our main aim was to accomplish the complete implementation of IM lorazepam, and secondly to introduce a standard regimen for monitoring vital signs to observe any unexpected adverse events when introducing the treatment paradigm in the complex organisation of our hospital.

Intervention

The intervention was to replace the use of IM diazepam with the use of IM lorazepam when a benzodiazepine was indicated for rapid tranquillization in adult inpatients hospitalised for mental health reasons. At the organisational level, this was directed by applying successive PDSA cycles [11].

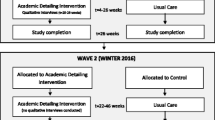

As recommended by many [12,13,13,14,], we initiated the QI intervention on a small scale in one department (Fig. 1) to ensure that we could go through the first PDSA cycle and learn about unexpected barriers and challenges before proceeding with a higher patient volume. When planning the first set of PDSA cycles, we described the evidence base for the QI project, the goals of the project, and produced a clinical treatment guideline including practical instructions for the use and dosage of lorazepam, as well as a standard for the monitoring of vital signs required after administration of IM lorazepam. As part of the do-phase in the first PDSA cycle, the involved healthcare personnel participated in a 2-h teaching session on the background and rationale for the change of treatment, as well as an introduction to the practical guidelines for administration and monitoring. After several iterations of the guideline, the intervention was spread to two departments, and after more iterations and three more PDSA cycles (Fig. 1) to the entire hospital.

The first set of PDSA cycles (Fig. 1) was conducted from October 2019 to November 2020. The clinical guideline was adjusted according to the knowledge obtained during the first set of PDSA cycles (Clinical treatment guideline—in Danish). As part of the second PDSA cycle (with the inclusion of two departments), staff members who could not attend the teaching session had access to e-learning with the same information but in a shorter format. According to the initial treatment guideline, respiratory rate (RR) should be measured every 10 min during the first hour and then every 30 min until two hours after the administration. The patients’ level of consciousness (aroused, awake, sleeping) should also be recorded. Blood pressure, pulse, ECG, and blood tests were optional.

For the second set of PDSA cycles (Fig. 1), lorazepam was released for use in the rest of the inpatient departments (from November 2020). A similar process with the teaching of all involved staff was performed, but this time the teaching material was provided as mandatory e-learning for all healthcare professionals. In addition, key local medical and nurse leaders were appointed to head the local QI project and participated in common project meetings. In the second set of PDSA cycles, there was a local focus on repeating the monitoring standard at physicians’ and nurses’ conferences, and at weekly meetings with the leaders of the departments.

Study of the intervention and data collected

Our outcome targets were:

(1) To switch from IM diazepam to IM lorazepam in all patients in need of a benzodiazepine for rapid tranquillization in clinical practice–and in this process examining the effectiveness of PDSA as an implementation method. The predefined target was the choice of IM lorazepam in > 80% of patients receiving a benzodiazepine IM as rapid tranquillisation.

(2) To ensure that IM lorazepam was a patient-safe procedure in a large complex mental health hospital by collecting data on respiratory rate and level of consciousness. The predefined target was sufficient documentation of safety data in > 80% of patients receiving IM lorazepam. This target was set to ensure both sufficient adherence to the clinical treatment guideline as well as taking into consideration a high turnover of clinicians who might not be familiar with the required level of documentation from day 1.

The impact of the intervention was assessed by central monitoring of the numbers of IM lorazepam and IM diazepam administrations in the subsequently included departments. Data were collected in a 3-month period before the intervention (July to September 2019), during the intervention (October 2019 to September 2021), and in a 3-month period post intervention (October to December 2021).

Each week we compiled a list of patients who had received IM lorazepam or IM diazepam. All data were monitored by the department of quality in the hospital. When the data did not meet the requirements defined as the standard, an audit of the patient medical record was performed to ensure that no patient safety issues were overlooked.

Analysis

Each medicine administration and the two-hour period after was labelled a case in the following and assigned a unique project ID. If tranquillity was needed again more than 4 h after the first administration, this was considered a new case and assigned a new project ID. Data were analysed as the mean number of lorazepam injections per month across the intervention phases (pre, PDSA 1.1–1.4, PDSA 2.1–2.3 and post). We plotted data in a control chart to investigate any non-random or cause-specific variation in the frequency of lorazepam administrations.

Ethical considerations

This study was a quality assessment of an acknowledged treatment paradigm; therefore, no formal approval from an ethics committee was required. We did not find any ethical problems in relation to this QI project since the existing practice was not recommended and could no longer be continued.

We followed the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines [15] for reporting QI projects.

Results

Replacement of IM diazepam with IM lorazepam

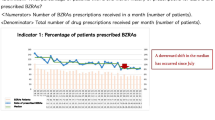

Table 1 shows the absolute numbers of patient cases receiving either IM diazepam or IM lorazepam pre and post intervention. All eligible patients for IM benzodiazepine were equivalent to the sum of cases receiving IM diazepam and IM lorazepam. Pre intervention, all eligible patients received IM diazepam. Tables 2 and 3 show the numbers of IM lorazepam injections during the first and second set of PDSA cycles, respectively. During the first PDSA cycle, seven IM lorazepam administrations per month were observed which gradually increased to 98.3 and 66.2 per month during the two last PDSA cycles, respectively. In the 3-months period after the intervention (1 October to 31 December 2021), 15 cases with IM diazepam injections were observed (administered to a total of 10 patients). In comparison, 349 lorazepam injections were administered during the same period, i.e., 349/364 = 96% of benzodiazepine administrations for rapid tranquillization were lorazepam. The total number of benzodiazepine injections per month was stable from the pre to post intervention period (Table 1). The mean dose in milligram diazepam equivalents remained stable from pre to post intervention (Table 1). Data from the intervention and post intervention periods are plotted as a control chart against time (Fig. 2) showing that non-random variation was not detected until PDSA cycle 2.2, where non-random variation was detected due to six points in a row trending upwards. This indicates that it was the sum of the interventions operating over time, more than any single element introduced in a specific PDSA cycle, that worked efficiently to ensure that lorazepam was prescribed instead of diazepam.

Control chart that displays data over time. Time (as depicted by a number of PDSA cycle and after (post) the intervention) on the x-axis. Number of lorazepam injections per month on the Y-axis. The horizontal solid line is the mean, and the dotted lines represent the lower and upper control limits (approximately 3 standard deviations on either side of the mean). Non-random variation due to upwards trend is marked with red (labelled ‘rule violation’, see explanation in text)

Standard monitoring regimen

Only one case had a RR below 12 which quickly rose again. None of the patients had to be transferred to more intensive care or had a prescription for flumazenil (benzodiazepine antidote).

The EMR of cases with no systematic documentation (i.e., entered in a prespecified field in the EMR) of RR were subsequently manually reviewed finding no signs of unexpected effects or unwanted sedation after the administration of lorazepam; none were somatically affected according to a review of their EMR.

As illustrated in Table 2, a review of EMR in PDSA cycle 1.2 showed that the dose of lorazepam in some cases was too low to result in tranquillity. Therefore, the recommended dose was adjusted in agreement with the summary of product characteristics recently released when the formulation was marketed in Denmark. In addition, in response to requests from physicians, a SmartPhrase with the correct prescription and wording was made available. A SmartPhrase is a predefined piece of text and prescription in the EMR that may be adjusted for the individual patient to facilitate adherence to the clinical treatment guideline. For the other local QI interventions, see Table 2. Kaizen boards were visual tools designed to help the local teams manage and succeed with the use and documentation of IM lorazepam and other continuous improvement efforts.

Since none of the cases had respiratory problems, we decided to revise the clinical guideline and reduce the required measurement interval of RR to once every 30 min for the first two hours and omit the requirement to routinely document the level of consciousness. If a patient became sedated, vital signs were recorded regularly at intervals agreed upon by the treating multidisciplinary team until the patient became active again.

In addition, each department received a complete list of cases receiving lorazepam injections, including whether the requirements of RR recordings had been met. Data were provided bi-weekly. When the targets were not met, the staff and physicians involved in the specific cases were contacted and interviewed about the reasons for not meeting the requirements to identify problems in the process. Many pointed out that it was difficult to remember in an acute, often chaotic, situation. Consequently, in week 29, 2021, we placed a notice in the medicine room next to the lorazepam IM injection fluid, “Remember to record the respiratory rate” (Table 2). In association with this, compliance with a recording of vital signs increased up to > 80% during the last month of the QI project and thus reaching the pre-defined target (Table 3).

Discussion

This QI project primarily aimed to replace the use of IM diazepam with IM lorazepam for acutely agitated inpatients in a complex mental health care setting rigorously conducting and reporting PDSA cycles as requested previously in the literature [23]. Secondly, we aimed to introduce a patient safety monitoring standard following the injection. Switching physicians’ prescribing habits from IM diazepam to IM lorazepam as the first choice was swift, successful, and endurable. The PDSA method was the primary QI method applied with a gradual, iterative, stepwise approach and continuous collection of data on a bi-weekly basis, documenting the intervention and feeding data back to the physicians. The interventions most closely connected with the clinical situation (i.e., written notice on the medication shelf at the point where the injection was prepared) seemed to be effective to increase the required recording of vital signs.

Effectiveness of the PDSA methodology to change physicians’ prescribing habits from diazepam to lorazepam can be explained by several factors. Acute agitation is a challenging condition to manage if the patient does not respond to the administered medication, and since the recommendation of IM lorazepam included a treatment guideline for dosing, physicians experienced this as an ease in their clinical work. In the first set of PDSA cycles, some physicians raised issues about the dosage, which was consequently adjusted in the guideline, making a higher dose possible under certain circumstances. In addition, most physicians agreed that lorazepam was an effective and tolerable medication for relieving patient agitation and, therefore, found the QI project clinically relevant and meaningful. Others have reviewed the translational barriers to implementing research findings in clinical practice [16] and mention the followings that were addressed in our study: formulating evidence-based guidelines, developing specific regional policies, outreach programs to local opinion leaders, and regional and institutional measures of compliance and processes of care. What is further emphasized [17] is the importance of including measures that demonstrate their impact on clinical outcomes. Such measures (e.g., time to sedation) were not included in the current study because the focus was on eliminating a prescribing practice that was clearly inappropriate after the lorazepam injection solution had been made available and because efficacy had already been documented in previous clinical trials [1, 2].

Compliance with the monitoring standard regimen took a longer time to implement, and we explored the lack of compliance. As part of the QI in our hospital, the Quality Development Office in the hospital administration would usually go Gemba to learn more about the root cause of the non-compliance [18, 19]. The concept of Gemba (a Japanese term for ‘the real place’) in the hospital setting involves administrators and managers directly observe the clinical workflow in question–in this case how IM lorazepam was prescribed, administered, monitored and documented. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the different centres in our hospital could not visit each other and meetings were held virtually. The involved departments, therefore, went Gemba to explore the problem locally. Two main problems were identified. First, the staff could not see the relevance of the repeated clinical measurements in a busy workload because the patients were clearly not somatically affected, and the staff’s attention was mainly on the patients’ mental state. Second, it was emphasised that physicians did not always place a formal prescription of the vital sign measurements together with the prescription of the medication. However, documentation of vital signs is an ordinary task of nurses, even without a formal prescription. The contradictions in these statements were addressed with some success during the following PDSA cycles. These problems occurred when we went from two departments to the inclusion of the entire hospital and at the same time changed the teaching to e-learning instead of face-to-face teaching which might have influenced the staff’s general understanding of the importance of the monitoring standard. Another important barrier was the high staff replacement rate which meant that the safety monitoring regimen had to be re-introduced to new staff repeatedly.

Other studies [20, 21] working with the improvement of medical documentation in a similar context to ours with guidelines, training, collection of data, and feedback to staff have resulted in an increase in documentation using PDSA cycles. In one study, the rating of the cardiopulmonary resuscitation status of patients was raised from 49% to > 80% [20]. One of the applied initiatives was to place a highly visible field in the patient’s EMR to remind the staff about what to do. Another study [21] using PDSA cycles to improve the documentation of pain assessment raised the documentation rate from 69% to > 90% using screensavers and bedside posters as visual reminders. In our study, the visual reminder considerably improved our documentation rate. A main difference to our study is that both studies [20, 21] made an early barrier analysis or conducted key informant interviews to assess the barriers to QI. This was not done systematically and rather late in our study since the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to go Gemba. For example, Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram analysis was used to identify valuable information about the potential barriers in due time. One of the barriers described in the above-mentioned studies [23, 24] was prioritizing patient treatment over documentation in a busy work environment. This finding was also observed in our study.

QI in mental health care has been the subject of several national initiatives [22] endorsing QI methods including PDSA cycles and other methods from continuous improvement. A review of QI of global mental health care recommended the development of transdiagnostic measures of patient-centred outcomes, common data elements integrated into electronic health records, and routine assessments of mental health outcomes as validated ways to stratify quality measures [23]. More specific examples with similarities to the QI project described in the present paper include a UK project to improve the physical health monitoring of patients with severe mental illness and treated with antipsychotic medications [24]. This study applied five consecutive PDSA cycles of two weeks duration to enhance communication with general practitioners as well as education of patients and home care staff to better acknowledge the value of physical health monitoring. The project resulted in improved patient engagement in monitoring, and a monitoring regimen more adherent to guidelines. Another QI project succeeded in improving the communication between the community mental health team and service users and carers, applying six PDSA cycles with actions such as successive improvement of medication leaflets and more efficient staff member use of time [25]. The project resulted in an increase in service user satisfaction from 60 to 78%. A recent review highlighted the widespread challenges with low adherence to methodological features in reported QI projects [10]. Many authors [12,13,13,14,] advocate the importance of small sample size with high fidelity before moving on to broader dissemination. Even though we did this in our first set of PSDA cycles, new challenges evolved. We assume that there was a lot of attention to the project in the first two involved departments in all staff groups, and the teaching was face-to-face, resulting in better compliance with recording vital signs whereas this was difficult to sustain on a larger scale with e-learning programs.

It is a limitation of the study that it was developed in a specific national context and the findings may not be generalizable to settings with very different organisational set-up, however, we believe that the process of applied learning is universal. Insufficient staff knowledge of the technical set-up and possibilities in the EMR may have acted as a barrier to a correct recording of the measurement of vital signs. The use of PDSA cycles should be followed up by other QI to determine where the obstacles were [11, 26].

Conclusion

This project confirmed that it was possible to increase the quality of treatment of acute agitation in a large inpatient mental health care setting by testing interventions in iterative PDSA cycles. PDSA methodology might be of value in other scenarios with the need for changes in prescribing and monitoring practice when used with sufficient feedback from local stakeholders and opinion leaders.

Data availability

The data for this project are confidential and not made publicly available.

References

Zaman H, Sampson SJ, Beck AL, Sharma T, Clay FJ, Spyridi S, Zhao S, Gillies D (2017) Benzodiazepines for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:Cd003079. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858

Kim HK, Leonard JB, Corwell BN, Connors NJ (2021) Safety and efficacy of pharmacologic agents used for rapid tranquilization of emergency department patients with acute agitation or excited delirium. Expert Opin Drug Saf 20(2):123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2021.1865911

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2015). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Violence and Aggression: Short-Term Management in Mental Health, Health and Community Settings: Updated edition. London: British Psychological Society. The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists

NHS Foundation Trust (2021) Rapid tranquillisation (RT) policy (including prescribing, post administration monitoring and remedial measures)-CLIN-0014–01-v8.2

Wilson MP, Pepper D, Currier GW, Holloman GH, Feifel D (2012) The psychopharmacology of agitation: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta psychopharmacology workgroup. West J Emerg Med 13(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6866

Rangachari P, Rissing P, Rethemeyer K (2013) Awareness of evidence-based practices alone does not translate to implementation: insights from implementation research. Qual Manag Health Care 22(2):117–125. https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0b013e31828bc21d

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC (2012) Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med 43(3):337–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024

Crisp H (2015) Building the field of improvement science. Lancet 26(385 Suppl 1):S4-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60320-8

Marshall M, Pronovost P, Dixon-Woods M (2013) Promotion of improvement as a science. Lancet 381(9864):419–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61850-9

Knudsen SV, Laursen HVB, Johnsen SP, Bartels PD, Ehlers LH, Mainz J (2019) Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects. BMC Health Serv Res 19(1):683. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4482-6

Ross S, Naylor C. (2017) Quality improvement in mental health. www.kingsfund.org.uk ed: King's Fund

Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE (2014) Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 23(4):290–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

Etchells E, Ho M, Shojania KG (2016) Value of small sample sizes in rapid-cycle quality improvement projects. BMJ Qual Saf 25(3):202–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005094

Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M (2015) How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. BMJ Qual Saf 24(5):325–336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003620

Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D (2016) SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 25(12):986–992. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411

Kalassian KG, Dremsizov T, Angus DC (2002) Translating research evidence into clinical practice: new challenges for critical care. Crit Care 6(1):11–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc1446

Wong BM, Sullivan GM (2016) How to write up your quality improvement initiatives for publication. J Grad Med Educ 8(2):128–133. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00086.1

Hallam CRA, Contreras C (2018) Lean healthcare: scale, scope and sustainability. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 31(7):684–696. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-02-2017-0023

Aij KH, Teunissen M (2017) Lean leadership attributes: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Organ Manag 31(7–8):713–729. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-12-2016-0245

Garcia CA, Bhatnagar M, Rodenbach R, Chu E, Marks S, Graham-Pardus A, Kriner J, Winfield M et al (2019) Standardization of inpatient CPR status discussions and documentation within the division of hematology-oncology at UPMC shadyside: results from PDSA cycles 1 and 2. J Oncol Pract 15(8):e746–e754. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.18.00416

Stocki D, McDonnell C, Wong G, Kotzer G, Shackell K, Campbell F (2018) Knowledge translation and process improvement interventions increased pain assessment documentation in a large quaternary paediatric post-anaesthesia care unit. BMJ Open Qual 7(3):e000319. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000319

Ross S, Naylor C (2017) Quality improvement in mental health. Ed: King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Quality_improvement_mental_health_Kings_Fund_July_2017_0.pdf

Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth-Rublee B, Ramanui P, O’Brien RW, Tomoyasu N, Pincus HA (2018) Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psych 27(1):30–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20482

Abdallah N, Conn R, Latif Marini A (2016) Improving physical health monitoring for patients with chronic mental health problems who receive antipsychotic medications. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 5(1):u210300.w4189. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u210300.w4189

Chowdhury P, Tari A, Hill O, Shah A (2020) To improve the communication between a community mental health team and its service users, their families and carers. BMJ Open Qual 9(4):e000914. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000914

Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S (2015) Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 24(3):228–238. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support for conducting this study was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB designed the educational intervention, developed the educational material, formulated the outcome measures and was the primary author of the manuscript. AD, KVB and KOH took part in the design of the study, managed the project and data collection, provided data feedback during the study period and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. IH participated in the design, management of the project and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was a quality assessment of an acknowledged treatment paradigm; therefore, no formal approval from an ethics committee and no consent to participate was required.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Baandrup, L., Dons, A.M., Bartholdy, K.V. et al. Changing prescribing practice for rapid tranquillization–a quality improvement project based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act method. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 59, 781–788 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02461-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02461-9