Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Pancreatic beta cell destruction in type 1 diabetes may be mediated by cytokines such as IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) signalling are activated by cytokines, but their significance in beta cells remains unclear. Here, we investigated the role of cytokine-induced ER stress and NFκB signalling in beta cell destruction.

Methods

Isolated mouse islets and MIN6 beta cells were incubated with IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α. The chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) was used to inhibit ER stress. Protein production and gene expression were assessed by western blot and real-time RT-PCR.

Results

We found in beta cells that inhibition of cytokine-induced ER stress with PBA unexpectedly potentiated cell death and NFκB-regulated gene expression. These responses were dependent on NFκB activation and were associated with a prolonged decrease in the inhibitor of κB-α (IκBα) protein, resulting from increased IκBα protein degradation. Cytokine-mediated NFκB-regulated gene expression was also potentiated after pre-induction of ER stress with thapsigargin, but not tunicamycin. Both PBA and thapsigargin treatments led to preferential upregulation of ER degradation genes over ER-resident chaperones as part of the adaptive unfolded protein response (UPR). In contrast, tunicamycin activated a balanced adaptive UPR in association with the maintenance of Xbp1 splicing.

Conclusions/interpretation

These data suggest a novel mechanism by which cytokine-mediated ER stress interacts with NFκB signalling in beta cells, by regulating IκBα degradation. The cross-talk between the UPR and NFκB signalling pathways may be important in the regulation of cytokine-mediated beta cell death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes results from the autoimmune-mediated dysfunction and destruction of pancreatic islet beta cells. Macrophages and T cells infiltrate islets and secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α. These cytokines are suspected mediators of beta cell dysfunction and death in type 1 diabetes, although the mechanisms remain unclear [1–3].

Exposure of beta cells to proinflammatory cytokines leads to activation of multiple signalling networks. Nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) has been identified as a key regulator of transcription factors and gene networks controlling cytokine-induced beta cell dysfunction and death [4–6]. NFκB is formed as a homo- or hetero-dimer comprising p50, p52 and p65 subunits, and is sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells as an inactive complex with inhibitor of κB-α (IκBα) protein [7]. Phosphorylation of IκBα by IκB kinase (IKK) leads to their ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation for NFκB activation. Activation of NFκB leads to changes in expression patterns of many pro- and anti-apoptotic genes, including iNos, Sod2, Fas, Ccl2 and IκBα.

Cytokine-induced NFκB activation also leads to the downregulation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ pump, SERCA2b [8]. This results in depletion of ER calcium stores and disruption of ER function. Newly synthesised secretory and membrane proteins are folded, processed and trafficked in the ER. Successful production of maturely folded proteins by the ER requires a variety of chaperones and foldases, while the targeting and degradation of misfolded proteins are facilitated by components of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. ER stress is a condition in which misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER as the result of disrupted ER function [9–11]. The sensing of ER stress by the transmembrane proteins protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), initiates signalling cascades collectively known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). The aim of the UPR is to restore ER homeostasis. This is achieved by a number of coordinated responses including: (1) inhibition of protein translation to reduce overload of the ER; (2) increased production of ER chaperones and foldases to augment protein-folding activity; and (3) upregulation of ERAD components to enhance protein elimination by the proteasome. Failure of these adaptive responses to restore ER homeostasis leads to a switch in UPR signalling to pro-apoptosis pathways, which can act through C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [9–11].

Since ER stress is capable of inducing apoptosis in beta cells [10, 11], its potential involvement in cytokine-mediated beta cell death in type 1 diabetes has been widely investigated [8, 10, 12–25]. Cytokine-stimulated beta cells are characterised by suppression of the adaptive UPR, which may contribute to a lowering of defence mechanisms and activation of the proapoptotic UPR [24, 26]. However, the ultimate fate of beta cells exposed to cytokines is likely to be influenced by the many signalling networks that are activated and the complex interactions between these systems. Very little is known about the nature of these interactions, or how they affect beta cell survival during cytokine attack.

In this study, we identified a novel interaction between the UPR and the NFκB signalling pathway in cytokine-exposed beta cells. We made the unexpected finding that inhibition of ER stress with the chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) potentiated cytokine-mediated beta cell death, and that this was due to NFκB activation and prolonged degradation of IκBα. Further analysis indicated that, rather than the presence or absence of ER stress, this response was associated with preferential activation of protein-degradation components of the adaptive UPR. These findings suggest that the balance of the adaptive UPR is critically important for NFκB activation and cell survival in cytokine-stimulated beta cells.

Methods

Cell/islet culture

MIN6 cells and islets isolated from adult C57BL/6J mice (Australian BioResources, Moss Vale, NSW, Australia) were cultured as previously described [24]. Procedures were approved by the Garvan Institute/St Vincent's Hospital Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee. Cells and islets were treated with 100 U/ml IL-1β, 250 U/ml IFN-γ and 100 U/ml TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). PBA (2.5 mmol/l) and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC; 50 μmol/l) plus Bay 11-7082 (10 μmol/l) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were used to inhibit ER stress and NFκB signalling pathways, respectively. Thapsigargin (Tg; 50 nmol/l) and tunicamycin (Tm; 1 μg/ml) (Sigma) were used to activate ER stress signalling. BMS-345541 (IKKi, 50 μmol/l) and MG132 (10 μmol/l) (Sigma) were used to inhibit the activities of IKK and the proteasome. Cell death was determined with the use of a Cell Death Detection ELISA (Roche Diagnostics, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) [24].

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described [24]. The following antibodies were used (1:1,000 dilution unless otherwise indicated): CHOP (sc-575) and total eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 α subunit (EIF2α) (sc-11386) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); phospho-PERK (Thr980, 16F8, 3179), phospho-EIF2α (Ser51, 9721), phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185, 9251), total JNK (9252) and total IκBα (9242) (Cell Signalling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); and β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma).

RNA analysis

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described [24]. Primer sequences are provided in electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1. The value obtained for each specific product was normalised to a control gene (cyclophilin A) and expressed as a fold change of the value in control extracts. Xbp1 splicing was assessed as previously described [15].

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA.

Results

PBA treatment inhibits cytokine-induced ER stress

We first tested whether PBA was capable of attenuating ER stress induced by cytokines in MIN6 cells. PBA has been found to have chaperone-like activity, although the exact mechanism of action is not fully understood [27]. In control MIN6 cells, treatment with the combination of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β + TNF-α + IFN-γ) for 24 h resulted in activation of ER stress, as evidenced by the increased phosphorylation of PERK (Fig. 1a, b) and EIF2α (Fig. 1a, e). The downstream proapoptotic protein, CHOP (Fig. 1a, f), was increased after cytokine treatment, as was the phosphorylation of JNK1 (46 kDa) (Fig. 1a, c) and JNK2 (54 kDa) (Fig. 1a, d). Activation of the UPR by cytokines was confirmed by increased mRNA expression of Atf4 (Fig. 1g) and Chop (also known as Ddit3) (Fig. 1h). Co-treatment of MIN6 cells with PBA inhibited cytokine-induced ER stress, as indicated by reduced phosphorylation of PERK (Fig. 1a, b) and EIF2α (Fig. 1a, e), decreased protein levels of CHOP (Fig. 1a, f) and mRNA expression of Atf4 (Fig. 1g) and Chop (Fig. 1h). The phosphorylation of JNK1/2 (Fig. 1a, c, d) was not affected by PBA treatment, indicating that cytokine-induced JNK1/2 activation is not solely a marker of ER stress.

Inhibition of ER stress potentiates cytokine-mediated cell death in MIN6 beta cells and mouse islets. MIN6 cells were incubated in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of PBA (2.5 mmol/l), in combination with or without IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) as indicated for 24 h. (a) Western blot was performed on protein extracts for PERK, JNK and EIF2α phosphorylation (p) and CHOP. Total (t) JNK, EIF2α and β-actin served as loading controls. Representative images are shown. pPERK (b), pJNK1 (46 kDa) (c), pJNK2 (54 kDa) (d), pEIF2α (e) and CHOP (f) were quantified by densitometry. pPERK and CHOP, pJNK1 and pJNK2, and pEIF2α were normalised to β-actin, tJNK and tEIF2α, respectively. Results are expressed as fold change compared with cytokine control. Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for Atf4 (g) and Chop (h). Cell death was determined using a cell death detection ELISA in MIN6 cells (i) and isolated mouse islets (j), corrected for DNA content in islets, and expressed as fold change compared with cytokine control. All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, PBA effect in each treatment group

PBA treatment potentiates cytokine-induced beta cell death

We tested whether the reduction in UPR activation caused by PBA affected cytokine-induced beta cell death. In control MIN6 cells, cytokine treatment led to a significant increase in cell death (Fig. 1i). Surprisingly, cytokine-induced beta cell death was further increased after co-treatment with PBA (Fig. 1i). This suggests that the inhibition of ER stress with PBA potentiates cytokine-induced cell death in MIN6 cells. We also tested in isolated mouse islets whether PBA altered the sensitivity of primary beta cells to cytokine-induced cell death. In accordance with the results in MIN6 cells, cytokine-induced cell death was significantly increased in mouse islets that were treated with cytokines + PBA compared with cytokines alone (Fig. 1j).

PBA potentiates cytokine-stimulated changes in NFκB-regulated gene expression

Because NFκB activation may play an important regulatory role in cytokine-mediated beta cell death [5, 6], we tested whether PBA treatment affected NFκB-regulated gene expression. In control MIN6 cells, treatment with cytokines for 24 h resulted in increased mRNA expression of genes known to be regulated by NFκB, namely iNos (Fig. 2a), Ccl2 (Fig. 2b), Fas (Fig. 2c), IκBα (Fig. 2d) and Sod2 (Fig. 2e). Cytokine treatment resulted in downregulation of Serca2b (also known as Atp2a2) (Fig. 2f), which is a known effect of NFκB activation [4]. Strikingly, the cytokine-stimulated changes in gene expression were potentiated in cells that were co-treated with PBA; the mRNA levels of iNos (Fig. 2a), Ccl2 (Fig. 2b), Fas (Fig. 2c), IκBα (Fig. 2d) and Sod2 (Fig. 2e) were further increased in cells treated with cytokines + PBA compared with cytokines alone. In addition, Serca2b mRNA levels were further reduced in cells treated with PBA (Fig. 2f). Similar results were found in mouse islets (ESM Fig. 1). These observations suggest that PBA treatment of beta cells leads to the potentiation of cytokine-stimulated changes in NFκB-regulated gene expression, thus providing evidence of novel cross-talk between the UPR and NFκB signalling pathways.

Inhibition of ER stress potentiates cytokine-mediated changes in gene expression. MIN6 cells were incubated in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of PBA (2.5 mmol/l), in combination with or without IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) as indicated for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for iNos (a), Ccl2 (b), Fas (c), IκBα (d), Sod2 (e) and Serca2b (f). All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, ††† p < 0.001, PBA effect in each treatment group

PBA treatment potentiates cytokine-mediated suppression of beta cell function and gene expression

We also tested whether PBA treatment affects the ability of cytokines to inhibit glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and suppress the expression of genes involved in beta cell function. Cytokine-mediated inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was potentiated in MIN6 cells that were co-treated with PBA (ESM Fig. 2a). This was not due to further reductions in expression of the insulin gene; conversely, PBA treatment protected against the cytokine-mediated downregulation of insulin mRNA levels (ESM Fig. 2b). PBA treatment also increased the expression of the islet-associated transcription factor, Pdx1 (ESM Fig. 2c). On the other hand, the ability of PBA to potentiate cytokine-mediated beta cell dysfunction was associated with suppression of the beta cell-associated glucose transporter, Glut2, and transcription factor, MafA (ESM Fig. 2d, e). Glut2 and MafA mRNA levels were reduced further in MIN6 cells that were co-treated with cytokines + PBA compared with cytokines alone (ESM Fig. 2d, e). Interestingly, the downregulation of both Glut2 and MafA is known to be dependent on NFκB activation, providing further evidence of an important relationship with the UPR signalling pathway.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated silencing of Chop does not affect cytokine-mediated cell death or NFκB-regulated gene expression

NFκB activity has previously been shown to regulate the expression of Chop in beta cells [4, 23], and that CHOP plays a role in cytokine-induced apoptosis [12, 23]. To assess the role of CHOP in our model of cytokine-stimulated cell death and NFκB-regulated gene expression, MIN6 cells were transfected with siRNA against Chop or control siRNA. Reduced cytokine-mediated Chop expression was observed in MIN6 cells transfected with Chop siRNA (ESM Fig. 3a). However, siRNA-mediated reduction of Chop expression had no effect on the cytokine-induced changes in the expression of NFκB-regulated genes iNos, Ccl2, Fas, IκBα, Sod2 or Serca2b (ESM Fig. 3b–g) or in cell death (ESM Fig. 3h). This suggests that Chop expression alone does not affect cytokine-stimulated cell death or NFκB-regulated gene expression.

NFκB activation is required for the effect of PBA to potentiate changes in cytokine-stimulated gene expression and cell death

We next tested whether the ability of PBA to potentiate changes in cytokine-stimulated gene expression and cell death was dependent on NFκB activation using the NFκB inhibitors PDTC and Bay 11-7082 [28]. In MIN6 cells treated overnight with PBA and then in combination with cytokines for 6 h, the mRNA levels of iNos (Fig. 3a), Ccl2 (Fig. 3b), Fas (Fig. 3c) and Sod2 (Fig. 3d) were significantly increased compared with cells treated with cytokines alone. This PBA-mediated potentiation of cytokine-induced gene expression was completely blocked after inhibition of NFκB activation with PDTC (Fig. 3a–d) or Bay 11-7082 (ESM Fig. 4a–d). Similarly, the ability of PBA to potentiate cytokine-induced cell death was inhibited after treatment of cells with PDTC (Fig. 3e) or Bay 11-7082 (ESM Fig. 4e). These observations suggest that the PBA-mediated potentiation of NFκB-regulated gene expression and cell death in response to cytokines results from increased NFκB activation or a pathway that depends on NFκB to be manifested.

The effect of ER stress inhibition in potentiating cytokine-mediated changes in gene expression and cell death is dependent on NFκB activation. MIN6 cells were incubated with IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) either alone (control, white bars) or in combination with PBA (2.5 mmol/l, black bars), PDTC (50 μmol/l, light grey bars) or both PBA and PDTC (dark grey bars). Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for iNos (a), Ccl2 (a), Fas (c) and Sod2 (d). (e) Cell death was determined using a cell death detection ELISA, and expressed as fold change compared with cytokine control. All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; ***p < 0.001 versus cytokine control; ††† p < 0.001 versus cytokine + PBA

PBA increases NFκB activity in response to cytokines via delayed replenishment of IκBα protein

We assessed the degradation and subsequent replenishment of IκBα protein after cytokine treatment in control and PBA-pretreated MIN6 cells. In control and overnight PBA-pretreated cells, cytokine exposure for 20 min led to similar decreases in IκBα protein (Fig. 4a, b). At subsequent time points, IκBα protein levels were progressively replenished in control cells, whereas they remained suppressed in cells precultured with PBA (Fig. 4a, b). This indicates that the enhanced activation of NFκB in PBA-treated cells is associated with delayed replenishment of its inhibitory protein, IκBα. This PBA-dependent delay in IκBα protein replenishment was reversed when IKK and proteasome inhibitors were added (Fig. 4c, d). This demonstrates that the delay in IκBα protein replenishment in PBA-treated cells results from increased protein degradation rather than reduced translation of IκBα.

Inhibition of ER stress prolongs cytokine-mediated IκBα degradation. MIN6 cells were incubated in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of PBA (2.5 mmol/l) overnight before stimulation with IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) for the indicated duration. (a, c) Western blot was performed on MIN6 cell protein extracts for IκBα; β-actin served as a loading control. Representative images are shown. (b, d) IκBα was quantified by densitometry, normalised to β-actin, and expressed as fold change compared with basal level in control. (c, d) BMS-345541 (IKKi, 50 μmol/l) and proteasome inhibitor (MG132, 10 μmol/l) were added after 20 min of cytokine stimulation. All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, PBA effect in each treatment group; † p < 0.05, effect of proteasome inhibition in PBA-treated cells

Cytokine-stimulated NFκB-regulated gene expression is potentiated following ER stress induction with thapsigargin (Tg), but not tunicamycin (Tm)

Tg and Tm are common agents used for ER stress induction. Their mechanisms of action differ: Tg depletes ER calcium stores, whereas Tm inhibits N-glycosylation of proteins. We tested whether the induction of ER stress with Tg or Tm influenced the sensitivity of MIN6 cells to cytokine-stimulated NFκB-regulated gene expression. MIN6 cells were pretreated overnight with Tg or Tm and then exposed to cytokines for 6 h. Strikingly, induction of ER stress with Tg potentiated the cytokine-stimulated increases in iNos (Fig. 5a), Ccl2 (Fig. 5b), IκBα (Fig. 5c) and Sod2 (Fig. 5d) mRNA levels. In contrast, after the induction of ER stress with Tm, the cytokine-stimulated increases in NFκB-regulated gene expression levels were similar to the control (Fig. 5a–d). This demonstrates that ER stress induction can potentiate cytokine-stimulated NFκB-regulated gene expression, but this response depends on the stressor.

Induction of ER stress with Tg, but not Tm, potentiates cytokine-mediated changes in gene expression and prolongs IκBα degradation in MIN6 beta cells. MIN6 cells were incubated with or without IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) after an overnight culture in control (white bars), Tg (50 nmol/l; black bars) or Tm (1 μg/ml; grey bars). Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for iNos (a), Ccl2 (b), IκBα (c) and Sod2 (d); ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; ††† p < 0.001, ER stress inducer effect in each treatment group. (e) Western blot was performed on protein extracts for IκBα; β-actin served as loading control. Representative images are shown. (f) IκBα was quantified by densitometry, normalised to β-actin, and expressed as fold change compared with basal level in control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ER stress inducer effect. All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments

ER stress induction delays the replenishment of IκBα protein after cytokine exposure

We tested whether ER stress induction with Tg or Tm affected the degradation or replenishment of IκBα protein after cytokine exposure. In control, Tg- and Tm-treated cells, cytokine exposure for 20 min led to similar decreases in IκBα protein (Fig. 5e, f). At subsequent time points, IκBα protein levels progressively increased in control cells, whereas they remained suppressed in cells pretreated with Tg (Fig. 5e, f). In cells pretreated with Tm, they displayed a significant time-dependent increase (p < 0.05), but at slightly lower levels than in control cells at 60 min (Fig. 5e, f). These findings suggest that Tg-induced ER stress is associated with suppression of IκBα protein replenishment following cytokine exposure. On the other hand, IκBα protein levels are replenished after Tm-induced ER stress, although at a slightly delayed rate. Taken together, the studies indicate that the differential effects of ER stress inducers on potentiation of cytokine-stimulated NFκB-regulated gene expression are associated with their ability to suppress IκBα protein replenishment. Furthermore, similar effects were observed after both ER stress induction (Tg treatment) and inhibition (PBA treatment).

PBA preferentially activates protein degradation components of the adaptive UPR

We next examined the influence of PBA on the pattern of adaptive UPR gene expression in control and cytokine-treated MIN6 cells. Cytokine activation of the UPR in beta cells is characterised by uniform suppression of the adaptive UPR [24, 26]. Consistent with this, treatment of MIN6 cells with cytokines for 24 h resulted in decreased mRNA expression of adaptive UPR genes, such as Bip (Fig. 6a), Grp94 (Fig. 6b), Orp150 (also known as Hyou1) (Fig. 6c), Erp72 (also known as Pdia4) (Fig. 6d), Herpud1 (Fig. 6e), p58 (also known as Dnajc3) (Fig. 6f), Edem1 (Fig. 6g) and Fkbp11 (Fig. 6h). Interestingly, co-treatment of MIN6 cells with PBA either potentiated or maintained the cytokine-mediated downregulation of ER chaperones (Bip, Grp94 and Orp150) and foldases (Erp72 and Herpud1) (Fig. 6a–e). In contrast, the expression of genes involved in facilitating protein degradation (p58, Edem1 and Fkbp11) was increased in PBA-treated cells (Fig. 6f–h). Similar results were found in mouse islets (ESM Fig. 5). These findings indicate that PBA preferentially activates degradation pathways of the UPR while potentiating the cytokine-mediated downregulation of ER-resident chaperones and foldases. This altered expression pattern of the adaptive UPR is associated with the potentiated cytokine activation of NFκB.

Inhibition of ER stress with PBA alters the pattern of adaptive UPR gene expression in MIN6 cells. MIN6 cells were incubated in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of PBA (2.5 mmol/l), in combination with or without IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) as indicated for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed, and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for Bip (a), Grp94 (b), Orp150 (c), Erp72 (d), Herpud1 (e), p58 (f), Edem1 (g), Fkbp11 (h). All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, ††† p < 0.001, PBA effect in each treatment group

Tg and Tm differentially regulate the pattern of adaptive UPR gene expression

Overnight culture of MIN6 cells with Tg and Tm resulted in increased expression of genes involved in the adaptive UPR, including the chaperone (Bip, Grp94 and Orp150), foldase (Erp72 and Herpud1) and degradation (p58, Edem1 and Fkbp11) components (Fig. 7a–h). However, the pattern of response differed markedly between the ER stressors. These differences were maintained after subsequent exposure of cells to the combination of cytokines (IL-1β + TNF-α + IFN-γ) for 6 h (Fig. 7a–h). Tm treatment induced a balanced adaptive UPR, with similar ∼3–4-fold increases in the expression levels of chaperone, foldase and degradation components. In contrast, Tg treatment induced an imbalanced adaptive UPR, with preferential activation of the protein degradation pathway. Tg treatment induced significantly smaller increases in chaperones and foldases (Fig. 7a–f), but equivalent increases in the degradation components, Edem1 and Fkbp11 (Fig. 7g, h) compared with Tm treatment. The similar responses observed after ER stress induction (Tg treatment) and inhibition (PBA treatment) suggest that the pattern of UPR gene expression, rather than the presence or absence of ER stress, is critically important in the regulation of cytokine-induced NFκB activity.

ER stress inducers Tg and Tm differentially regulate adaptive UPR gene expression in MIN6 cells. MIN6 cells were incubated with or without IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) after an overnight culture in control (white bars), Tg (50 nmol/l; black bars) or Tm (1 μg/ml; grey bars). Total RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed, and analysed by real-time RT-PCR for Bip (a), Grp94 (b), Orp150 (c), Erp72 (d), Herpud1 (e), p58 (f), Edem1 (g) or Fkbp11 (h). All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, ††† p < 0.001, ER stress inducer effect in each treatment group; ‡ p < 0.05, ‡‡ p < 0.01, ‡‡‡ p < 0.001, difference between ER stress inducers

Tm pretreatment protects against the cytokine-mediated decrease in XBP1 activation

The transcription factor XBP1 regulates the expression of many adaptive UPR genes [29, 30]. As expected, Xbp1 splicing (activation) was reduced after cytokine treatment in control MIN6 cells (Fig. 8). In cytokine-treated cells cocultured with PBA or Tg, Xbp1 splicing remained suppressed (Fig. 8). In contrast, cells co-treated with Tm were protected against the cytokine-mediated reduction in Xbp1 splicing (Fig. 8). These findings demonstrate a clear association in PBA- and Tg-treated cells between suppression of Xbp1 splicing, an imbalanced pattern of adaptive UPR gene expression, and potentiated NFκB activity and cell death (Fig. 9). The upregulation of Xbp1 splicing in Tm-treated cells is associated with a balanced UPR and typical NFκB activity after cytokine exposure (Fig. 9).

ER stress agents differentially affect cytokine-mediated inhibition of Xbp1 splicing in MIN6 cells. MIN6 cells were incubated with (black bars) or without (white bars) IL-1β (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) in the absence or presence of PBA (2.5 mmol/l), Tg (50 nmol/l) or Tm (1 μg/ml). Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed. Xbp1 cDNA was amplified by PCR and digested with PstI, which cuts unprocessed Xbp1 into fragments. Processed (activated) Xbp1 lacks the restriction site and remains intact. Processed (intact) and unprocessed (cut) Xbp1 were quantified by densitometry. The value obtained for processed Xbp1 was expressed as a ratio of the total (processed + unprocessed) Xbp1 mRNA level for each sample. These ratios are expressed as fold change in the ratio in the control. All results are mean ± SEM determined from at least three experiments; ***p < 0.001, cytokine effect in each group; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, ††† p < 0.001, difference from control

Proposed model for the interaction between the balance of adaptive UPR and cytokine-mediated NFκB activation. (a) The activation of a balanced adaptive UPR, characterised by similar changes in the expression of protein folding and degradation components as well as enhanced XBP1 activation, was observed after cytokine stimulation in tunicamycin-treated cells. This allows normal IκBα replenishment and typical activation of NFκB. (b) The activation of an imbalanced adaptive UPR, characterised by a preferential increase in the expression of protein degradation components over chaperones and reduced XBP1 activation, was observed after cytokine stimulation in PBA- and thapsigargin-treated cells. This results in a delayed IκBα replenishment and potentiated NFκB activation

Discussion

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ activate ER stress and NFκB signalling pathways, both of which have been implicated as possible mediators of beta cell death in type 1 diabetes. Here, we investigated the role of these signalling events in beta cell death. Beta cells treated with the ER stress-inhibiting agent, PBA, displayed further increases in cytokine-mediated beta cell death and NFκB-regulated gene expression. This occurred after an increase in the degradation of IκBα protein, which results in prolonged NFκB activation. However, the relationship between ER stress and NFκB signalling does not depend solely on ER stress activation. Treatment of cells with the ER stress inducer Tg, but not Tm, also resulted in potentiated NFκB-regulated gene expression in association with suppression of IκBα protein replenishment. Gene expression analysis revealed this to be dependent on the pattern of the adaptive UPR activated in response to these agents. A balanced adaptive UPR, which is associated with enhanced XBP1 activation, protects against hyperactivation of NFκB. An adaptive UPR that favours protein degradation over protein folding is associated with reduced XBP1 activation. This novel interaction between adaptive UPR and NFκB signalling pathways has important implications for the understanding and treatment of type 1 diabetes.

Regulation of the UPR in response to cytokines

The mechanisms that coordinate the adaptive UPR are poorly understood. Selective activation (or selective perpetuation) of signalling through the various arms of ER stress transduction has been proposed to regulate the switch between adaptive and apoptotic UPR signalling [31]. Perhaps similar mechanisms regulate the independent components within the adaptive UPR. The present study suggests that XBP1 activation may play a role regulating the balance between protein folding and degradation in cytokine-stimulated beta cells. This may also be relevant for nutrient-induced UPR activation in beta cells [32, 33]. However, coordination with the other branches of ER stress signalling, including XBP1-independent IRE1α activity, is crucial for the UPR irrespective of the stimulus. In line with this, experimental manipulation of XBP1 activation alone has profound effects on the UPR as well as on the optimisation of beta cell gene expression, insulin secretion and apoptosis [20, 34]. ER stress-independent factors, including JNK [24, 35], DP5 [16], JunB [19], Mcl-1 [17] and PPARγ [21], may also influence cytokine activation of the UPR in beta cells. These factors may act independently of effects on inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription and nitric oxide production, which is a key regulator of the UPR in cytokine-stimulated beta cells [8, 12, 24]. The contribution of the UPR to cytokine-mediated apoptosis in beta cells may depend on the complex interactions of many ER stress-dependent and -independent signalling networks, which are in turn regulated by the severity and duration of cytokine exposure. Reflective of this may be the conflicting findings among studies examining the effect of reducing CHOP on cytokine-induced apoptosis [12, 15, 23]. The present study suggests that the balance within the adaptive UPR and its influence on the NFκB signalling network is an important additional regulatory mechanism for beta cell survival.

Interaction between the UPR and NFκB pathways in beta cells

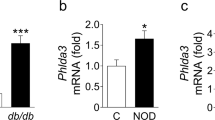

This study suggests a novel interaction of the adaptive UPR with the NFκB signalling pathway via regulation of IκBα degradation (Fig. 9). The interaction is dependent on the nature of the UPR and is evident after either ER stress activation or inhibition. Thus, rather than forming an archetypal feedback loop between NFκB activation and ER stress induction, the response is observed under conditions of an imbalanced adaptive UPR, with preferential activation of the protein-degradation components. Increased IκBα degradation is facilitated by enhanced proteasomal activity, which is highly dependent on the ERAD network. This is distinct from the previously reported mechanisms by which ER stress activates NFκB via the PERK–eIF2α pathway [36–38] or by IRE1-mediated activation of TNF receptor-associated factor 2 [39, 40]. Interestingly, an increase in ER stress markers and NFκB target genes has been observed in islets of diabetic NOD mice in the prediabetic period [25], raising the possibility that interaction between the pathways is important in the development of type 1 diabetes.

Implications for the use of ER stress inhibitors as therapeutic agents

Restoring ER homeostasis with chemical chaperones has emerged as a novel therapeutic approach for many diseases that involve ER stress. The mechanism of action of chemical chaperones is not fully understood [27]. Our findings suggest that part of the mechanism whereby PBA may alleviate ER stress is by enhancing the expression of genes involved in ERAD. However, the associated activation of the proteasome may affect protein degradation more broadly, and thus influence other cellular processes. Because of the effect on IκBα degradation and subsequent NFκB activation, our studies indicate that, under conditions of inflammation, this may have a profound influence on cell survival. Many of the diseases of protein misfolding and ER stress also involve, or are accompanied by, inflammation. This may be relevant in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes and in obesity [41]. Thus our findings illustrate an important consideration for the therapeutic use of chemical chaperones in the treatment of these diseases. Future studies should assess the effects of ER stress inhibitors on UPR status (i.e. the pattern of adaptive and proapoptotic UPR components) rather than the mere presence or absence of ER stress.

Implications for UPR-NFκB interaction in cell survival under inflammatory stress

ER stress and the ensuing UPR have been implicated in various inflammatory conditions, probably arising from the increased demand for the production and secretion of proteins such as cytokines and viral proteins [42]. Active NFκB signalling is indicative of the presence of inflammation in the cell vicinity to help cytokines and immune cells to clear the infection. Activation of NFκB signalling leads to the production of cytokines that are capable of inducing an ER stress response with a suppressed adaptive UPR. This approach may help in the action of cytokines and immune cells to contain the production of infectious antigens. However, this strategy also limits the yield of other cellular proteins that are essential for survival. Therefore cellular functions need to be maintained in this situation by concurrent suppression of the degradative machinery. Interventions that alter this balance in the adaptive UPR can result in a different cellular response. In an inflammatory environment, favouring protein degradation over protein folding can lead to increased proteasome activity and loss of cellular proteins over time. Simultaneous activation of NFκB in a beta cell can be influenced by this increased proteasome activity because of the continual loss of IκBα protein. Although NFκB signalling is pro-survival in immune cells, it can be apoptotic in beta cells [6]. Hence, a switch in the balance of the UPR to favour NFκB activation can lead to potentiated beta cell death. This interaction between UPR and NFκB signalling may represent an opportunity for the development of new treatments for inflammatory conditions including type 1 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- ATF6:

-

Activating transcription factor 6

- CHOP:

-

C/EBP homologous protein

- eIF2α:

-

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 α subunit

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD:

-

ER-associated degradation

- IκBα:

-

Inhibitor of κB-α

- IKK:

-

IκB kinase

- IRE1:

-

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1

- JNK:

-

Jun N-terminal kinase

- NFκB:

-

Nuclear factor-κB

- PBA:

-

4-Phenylbutyric acid

- PDTC:

-

Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

- PERK:

-

PKR-like ER kinase

- PKR:

-

Protein kinase RNA-activated

- siRNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- Tg:

-

Thapsigargin

- Tm:

-

Tunicamycin

- XBP1:

-

X-box binding protein 1

References

Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F (2009) The role of inflammation in insulitis and beta-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5:219–226

Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL (2003) Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes mellitus. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 4:291–299

Thomas HE, McKenzie MD, Angstetra E, Campbell PD, Kay TW (2009) Beta cell apoptosis in diabetes. Apoptosis 14:1389–1404

Cardozo AK, Heimberg H, Heremans Y et al (2001) A comprehensive analysis of cytokine-induced and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem 276:48879–48886

Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jorns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL (2005) Mechanisms of pancreatic beta-cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes 54:S97–S107

Eldor R, Yeffet A, Baum K et al (2006) Conditional and specific NF-kappaB blockade protects pancreatic beta cells from diabetogenic agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:5072–5077

Karin M, Lin A (2002) NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nature Immunol 3:221–227

Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J et al (2005) Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 54:452–461

Walter P, Ron D (2011) The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334:1081–1086

Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK, Cnop M (2008) The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev 29:42–61

Kaufman RJ, Back SH, Song B, Han J, Hassler J (2010) The unfolded protein response is required to maintain the integrity of the endoplasmic reticulum, prevent oxidative stress and preserve differentiation in beta-cells. Diabetes Obes Metab 12(Suppl 2):99–107

Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M et al (2001) Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10845–10850

Kharroubi I, Ladriere L, Cardozo AK, Dogusan Z, Cnop M, Eizirik DL (2004) Free fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-kappaB and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology 145:5087–5096

Chambers KT, Unverferth JA, Weber SM, Wek RC, Urano F, Corbett JA (2008) The role of nitric oxide and the unfolded protein response in cytokine-induced beta-cell death. Diabetes 57:124–132

Akerfeldt MC, Howes J, Chan JY et al (2008) Cytokine-induced beta-cell death is independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Diabetes 57:3034–3044

Gurzov EN, Ortis F, Cunha DA et al (2009) Signaling by IL-1beta+IFN-gamma and ER stress converge on DP5/Hrk activation: a novel mechanism for pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 16:1539–1550

Allagnat F, Cunha D, Moore F, Vanderwinden JM, Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK (2011) Mcl-1 downregulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines and palmitate is an early event contributing to beta-cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 18:328–337

Tonnesen MF, Grunnet LG, Friberg J et al (2009) Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB or Bax prevents endoplasmic reticulum stress—but not nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis in INS-1E cells. Endocrinology 150:4094–4103

Gurzov EN, Ortis F, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, Eizirik DL (2008) JunB inhibits ER stress and apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS One 3:3030

Allagnat F, Christulia F, Ortis F et al (2010) Sustained production of spliced X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis. Diabetologia 53:1120–1130

Weber SM, Chambers KT, Bensch KG, Scarim AL, Corbett JA (2004) PPARgamma ligands induce ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells: ER stress activation results in attenuation of cytokine signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287:E1171–E1177

Satoh T, Abiru N, Kobayashi M et al (2011) CHOP deletion does not impact the development of diabetes but suppresses the early production of insulin autoantibody in the NOD mouse. Apoptosis 16:438–448

Shao C, Lawrence MC, Cobb MH (2010) Regulation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) expression by interleukin-1 beta in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 285:19710–19719

Chan JY, Cooney GJ, Biden TJ, Laybutt DR (2011) Differential regulation of adaptive and apoptotic unfolded protein response signalling by cytokine-induced nitric oxide production in mouse pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 54:1766–1776

Tersey SA, Nishiki Y, Templin AT et al (2012) Islet beta-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress precedes the onset of type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse model. Diabetes 61:818–827

Pirot P, Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK (2006) Interferon-gamma potentiates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced death by reducing pancreatic beta cell defence mechanisms. Diabetologia 49:1229–1236

Engin F, Hotamisligil GS (2010) Restoring endoplasmic reticulum function by chemical chaperones: an emerging therapeutic approach for metabolic diseases. Diabetes Obes Metab 12(Suppl 2):108–115

Pierce JW, Schoenleber R, Jesmok G et al (1997) Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IkappaBalpha phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J Biol Chem 272:21096–21103

Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH (2003) XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 23:7448–7459

Yoshida H, Matsui T, Hosokawa N, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K, Mori K (2003) A time-dependent phase shift in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Dev Cell 4:265–271

Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ (2007) That which does not kill me makes me stronger: adapting to chronic ER stress. Trends Biochem Sci 32:469–476

Laybutt DR, Preston AM, Akerfeldt MC et al (2007) Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 50:752–763

Elouil H, Bensellam M, Guiot Y et al (2007) Acute nutrient regulation of the unfolded protein response and integrated stress response in cultured rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 50:1442–1452

Lee AH, Heidtman K, Hotamisligil GS, Glimcher LH (2011) Dual and opposing roles of the unfolded protein response regulated by IRE1alpha and XBP1 in proinsulin processing and insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8885–8890

Pirot P, Ortis F, Cnop M et al (2007) Transcriptional regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress gene chop in pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 56:1069–1077

Deng J, Lu PD, Zhang Y et al (2004) Translational repression mediates activation of nuclear factor kappa B by phosphorylated translation initiation factor 2. Mol Cell Biol 24:10161–10168

Wu S, Tan M, Hu Y, Wang JL, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ (2004) Ultraviolet light activates NFkappaB through translational inhibition of IkappaBalpha synthesis. J Biol Chem 279:34898–34902

Jiang HY, Wek SA, McGrath BC et al (2003) Phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is required for activation of NF-kappaB in response to diverse cellular stresses. Mol Cell Biol 23:5651–5663

Kaneko M, Niinuma Y, Nomura Y (2003) Activation signal of nuclear factor-kappa B in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress is transduced via IRE1 and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2. Biol Pharm Bull 26:931–935

Zhang K, Kaufman RJ (2008) From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 454:455–462

Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS (2011) Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Ann Rev Immunol 29:415–445

He B (2006) Viruses, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and interferon responses. Cell Death Differ 13:393–403

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia.

Contribution statement

All authors contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and the drafting of the article or its critical revision. All authors gave approval of the version to be published.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 888 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

(PDF 1123 kb)

ESM Fig. 3

(PDF 2570 kb)

ESM Fig. 4

(PDF 1111 kb)

ESM Fig. 5

(PDF 913 kb)

ESM Table 1

(PDF 68 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, J.Y., Biden, T.J. & Laybutt, D.R. Cross-talk between the unfolded protein response and nuclear factor-κB signalling pathways regulates cytokine-mediated beta cell death in MIN6 cells and isolated mouse islets. Diabetologia 55, 2999–3009 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2657-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2657-3