Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Recent publications of data extracted from population registries have suggested a possible relationship between treatment with insulin glargine and increased incidence of cancer/breast cancer. The aim of the present study was investigate this possible relationship using data from the manufacturer’s (sanofi-aventis) pharmacovigilance database.

Methods

We analysed the manufacturer’s (sanofi-aventis) pharmacovigilance database for all randomised clinical trials (RCTs; Phase 2–4) comparing insulin glargine with any comparator in type 1 or type 2 diabetes. We identified all serious adverse events coded under the System Organ Class of ‘neoplasms, benign, malignant and unspecified’. Treatment-emergent neoplasms judged to be malignant were included in this analysis.

Results

The database included 31 studies, 12 in type 1 diabetes and 19 in type 2 diabetes. Twenty compared insulin glargine with NPH insulin, 29 were parallel-group studies and two had a crossover design. Studies were generally of 6 months’ duration, except for trial reference number 4016 (n = 1,017), which had a duration of 5 years. Overall, 10,880 people were included in the analysis (insulin glargine, 5,657; comparator, 5,223). Forty-five people (0.8%) vs 46 people (0.9%) reported 52 and 48 cases of malignant cancer in the insulin glargine and comparator groups, respectively (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.60–1.36). Skin (12 people with 16 events vs six people with seven events, RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.69–4.92), colon and rectum (six vs ten people, RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.20–1.52), breast (four vs six people, RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17–2.18) and gastrointestinal tract (six vs four people, RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.39–4.90) were the most commonly reported sites.

Conclusions/interpretation

In these 31 RCTs, insulin glargine was not associated with an increased incidence of cancer, including breast cancer, compared with the comparator group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent publications of data extracts from population registries have triggered debate about a potential relationship between treatment with insulin glargine (A21Gly,B31Arg,B32Arg human insulin) and an increased incidence of cancer or breast cancer [1–4]. Here, we fulfil an obligation to report the evidence from randomised clinical trials (RCTs) within the manufacturer’s database.

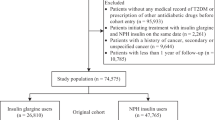

All RCTs sponsored by sanofi-aventis that compared the use of insulin glargine with another active comparator in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes and had a treatment duration of at least 4 weeks were included in this analysis. These studies included people with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and were either part of the initial development plan for the registration of the product (Phase 2 and 3) or conducted after the commercial launch of insulin glargine (Phase 4 studies).

Methods

As it is obligatory for all sponsored trials routinely to report serious adverse events to the manufacturer, and as the manufacturer has a database of such studies, no literature search was performed. Only RCTs that compared insulin glargine with an active comparator and that had a final clinical study report available for review on 15 May 2009 were included in this analysis.

Studies and ascertainment of malignancy

A thorough review of the sanofi-aventis safety database for the identified studies was performed to assess the incidence of any malignancies that led to reports of serious adverse events during the conduct of the trials. All RCTs of insulin glargine were included. All serious adverse events coded in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) System Organ Class of neoplasms—benign, malignant and unspecified—were included in the evaluation [5]. An adverse event is classified as serious if it fulfils the criteria set down by the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), that is if it: is life-threatening or results in death; requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation; results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity; is a congenital anomaly/birth defect; or is another ‘medically important’ event that may jeopardise the study participant or may require intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in the definition above [6]. The ICH recommends that cancers are characterised as ‘medically important’ adverse events and, therefore, are classified as serious adverse events [6].

All such identified records in the sanofi-aventis pharmacovigilance database were reviewed, by treatment, by the manufacturer’s drug safety personnel with experience of adverse event reporting, and only treatment-emergent neoplasms judged to be malignant were included, independent of treatment group. Each person was counted only once, although separate counts for people and cases are provided if more than one malignancy was reported in the same person. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for insulin glargine relative to the comparator for the total incidence of malignancies and for individual classifications using all identified RCTs in type 1 and type 2 diabetes combined.

Results

The Clintrace sanofi-aventis safety database contains 31 eligible studies. Twelve studies were performed in people with type 1 diabetes and 19 studies in people with type 2 diabetes; most of the studies compared insulin glargine with NPH insulin (20 studies). Nearly all (29) were parallel-group trials (two had a crossover design). Details of these studies are summarised in Table 1. Most studies were open label, 19 were of around 6 months in duration, with six of longer duration, notably the retinopathy study 4016, which had a duration of 5 years [7].

Overall, 10,880 people were included in the analysis, with 5,657 people randomised to insulin glargine and 5,223 people randomised to the comparator, representing a total follow-up time of 4,711 and 4,524 person-years, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the participants were comparable between treatment groups (Table 2).

Overall, there was no difference in the incidence of malignancies between insulin glargine-treated people and the comparator group (Table 3), with 52 cases of malignant cancer documented as a serious treatment-emergent event in 45 people in the insulin glargine group (0.8%) and 48 cases in 46 people in the comparator group (0.9%). Among such malignancies, most occurred in people with type 2 diabetes, with 45 cases in 39 people in the insulin glargine group (1.0%) and 46 cases in 44 people in the comparator group (1.2%).

The corresponding RR for malignant cancer with insulin glargine compared with the comparator is 0.90 (95% CI 0.60–1.36).

Four cases of malignant breast cancer were reported in the insulin glargine group (0.1%) and six cases in the control group (0.1%). The RR for breast cancer is 0.62 (95% CI 0.17–2.18).

These data were primarily driven by the findings in the 5 year RCT (study 4016) that compared insulin glargine (n = 514) with NPH insulin (n = 503) in people with type 2 diabetes who were randomised and received treatment [7, 8]. In that study, the overall number of people with neoplasms was similar in the insulin glargine and NPH insulin groups (57 [11.1%] and 62 [12.3%] people, respectively) [8]. When considering only the number of people in the retinopathy study with malignant neoplasms reported as serious treatment-emergent events, the rate was also similar in both groups (insulin glargine vs NPH insulin, 23 cases in 20 people [3.9%] vs 32 cases in 31 people [6.2%]). Finally, the number of people with breast cancer reported as a serious adverse event in that study was similar between the two treatment groups (three [0.6%] vs four [0.8%] cases – there was also an additional fifth case in the NPH insulin group, although this was reported as a non-serious adverse event).

Table 4 summarises the sites of all malignancies in the pooled studies comparing insulin glargine with comparator. The most frequently reported site (insulin glargine vs comparator) included the skin (16 events in 12 people [0.2%] vs seven events in six [0.1%] people, RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.69–4.92), colon and rectum (six [0.1%] vs ten [0.2%], RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.20–1.52), breast (four [0.1%] vs six [0.1%], RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17–2.18) and gastrointestinal tract (six [0.1%] vs four [0.1%], RR 1.38; 95% CI 0.39–4.90).

With respect to the type of malignancy, at least two more tumours were reported in the comparator group vs the insulin glargine group for the following classifications: colon and rectum (ten [0.2%] vs six [0.1%]), prostate (three [0.1%] vs one [0.0%]), neurological (two [0.0%] vs zero [0.0%]) and bladder (two [0.0%] vs zero [0.0%]). Conversely, there were nine more cases of skin cancer in the insulin glargine group compared with the comparator group (16 cases in 12 people [0.2%] vs seven cases in six people [0.1%]), including an imbalance of six (0.1%) to one (0.0%) for malignant melanoma. However, in the 5 year Study 4016, the incidence of all melanomas (documented as serious and non-serious adverse events) was not different between treatment groups (three each, with one case in the comparator [NPH insulin] group and two in the insulin glargine group reported as serious adverse events).

Within the sanofi-aventis safety database, in addition to the RCTs, there are 26 completed uncontrolled studies with insulin glargine, involving a total of 68,201 participants with type 1 or type 2 diabetes treated for up to 3 years. The data from these 26 uncontrolled studies represent a total follow-up time of 22,074 person-years for insulin glargine treatment.

In total, there were 111 cases of malignancy, including nine cases of breast cancer, reported in these studies. The overall cancer rate is estimated to be 5.0 cases per 1,000 person-years (111 out of 22,074 person-years) and the breast cancer rate is estimated to be 82 cases per 100,000 person-years (that is, nine out of 11,027 person-years—the denominator here being the exposure of women in the type 2 diabetes RCTs). In investigator-sponsored trials and product registries (intensified monitoring) for which no enrolment figures are available, the sanofi-aventis safety database contains an additional 75 individuals with malignancies, including nine cases of breast cancer.

Discussion

Based on our analysis of 31 RCTs, insulin glargine was not associated with an increased incidence of cancer, including breast cancer, when compared with the control/comparator group.

The overall incidence of cancer in the trials included in this analysis was lower in people with type 1 diabetes than in those with type 2 diabetes, perhaps because the former were younger and less obese than the people with type 2 diabetes (Table 2), and were exposed for a shorter time. Obesity increases the risk of colon cancer by as much as 1.5- to 2-fold and accounts for up to 35% of the total incidence of colon cancer [9]. In terms of age, the prevalence of cancer increases with increasing age and peaks in people aged 75 years or older [10, 11]. People with type 2 diabetes in this analysis were typically in their mid to late fifties and, thus, the majority were at an age associated with greater risk for cancer compared with the people with type 1 diabetes.

The results presented are based on formal RCTs, which represent level 1—the highest level—of evidence-based study design. Another advantage of the present analysis is that the clinical trials database reviewed here included a large number of people (n = 10,880), allowing the opportunity to identify rarer adverse events. Furthermore, the events were recorded reasonably accurately, as in any RCT, as the monitoring of adverse events followed the rules of good clinical practice and international pharmacovigilance regulations [12]. Finally, our analysis included one long-term 5 year controlled study that showed comparably reassuring findings, with no differences in the incidence of cancers between patients treated with insulin glargine and patients treated with NPH insulin.

Nevertheless, this analysis must be considered in light of some limitations. The duration of most of the studies was relatively short (mostly 6 months) and does not reflect the lifetime risk for cancer, while only one study was longer than 1 year. Nevertheless, if growth promotion is postulated as the mechanism of any increased cancer risk, it would appear early in the use of any therapeutic entity. None of the RCTs was specifically designed to evaluate the risk of cancer with insulin glargine, although all had mandatory reporting of adverse events, including treatment-emergent neoplasms. Randomised controlled trials may not fully reflect real-life clinical practice; investigators may, for example, be less likely to include people with previous malignancies. People using thiazolidinediones, which have been suggested as protective against breast or pancreatic cancer [13, 14] and linked with increases in bladder cancer, [13] were often not included in the insulin studies, owing to the relative or absolute labelling restrictions in participating countries. Finally, the number of malignancies reported here may differ slightly from the published numbers for each study owing to differences in reporting methods; for example, only cases classified as serious treatment-emergent events were included in this analysis, whereas the original publications may have included cases classified as non-serious or serious. In addition, we only included treatment-emergent cases, whereas some of the publications may have included pre-existing cases.

However, analysis of the 26 uncontrolled trials with insulin glargine shows that the overall cancer rate is estimated to be 5.0 cases per 1,000 person-years. Compared with the age-adjusted incidence rate of 4.63 per 1,000 per year in the USA (based on cases diagnosed in 2002–2006 from 17 geographic areas included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results [SEER] programme), there was no indication of increased cancer risk in people with diabetes using insulin glargine. However, we acknowledge that under-reporting of cancer events can occur in uncontrolled observational studies, where follow-up with physicians is not always possible and, therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.

For breast cancer, the incidence rate in women participating in non-interventional trials of insulin glargine may be estimated to be 82 cases per 100,000 person-years. Compared with the incidence rate of 124 per 100,000 women per year in the US SEER database, no safety signal for breast cancer was identified with the use of insulin glargine in these clinical trials.

In conclusion, these data suggest that insulin glargine is not associated with an increased risk of cancer compared with the different comparators (mainly NPH insulin). While the data provide useful reassuring and contributory information regarding the safety of insulin glargine, they underscore the importance of continued long-term follow up of participants in clinical trials.

Abbreviations

- ICH:

-

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use

- RCT:

-

randomised clinical trial

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

References

Colhoun HM, on behalf of the SDRN Epidemiology Group (2009) Use of insulin glargine and cancer incidence in Scotland: a study from the Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Diabetologia 52:1755–1765

Currie CJ, Poole CD, Gale EAM (2009) The influence of glucose-lowering therapies on cancer risk in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 52:1766–1777

Hemkens LG, Grouven U, Bender R et al (2009) Risk of malignancies in patients with diabetes treated with human insulin or insulin analogues: a cohort study. Diabetologia 52:1732–1744

Jonasson JM, Ljung R, Talbäck M, Haglund B, Gudbjörnsdòttir S, Steineck G (2009) Insulin glargine use and short-term incidence of malignancies—a population-based follow-up study in Sweden. Diabetologia 52:1745–1754

Northrup Grumman (2009) Medical dictionary for regulatory activities. Available at www.meddramsso.com/MSSOWeb/index.htm, accessed 10 August 2009

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (2009) ICH Guidelines. Available at www.ich.org/UrlGrpServer.jser?@_ID=276&@_TEMPLATE=254, accessed 10 August 2009

Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, McGill JB et al (2009) Similar progression of diabetic retinopathy with insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a long-term, randomised, open-label study. Diabetologia 52:1778–1788

Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, McGill JB et al (2009) Similar risk of malignancy with insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: findings from a 5 year randomised, open-label study. Diabetologia 52:1971–1973

Huang XF, Chen JZ (2009) Obesity, the PI3K/Akt signal pathway and colon cancer. Obes Rev. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1789X.2009.00607.x

Cancer Research UK (2009) UK cancer incidence statistics by age. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/age/?a=5441, accessed 10 August 2009

World Health Organisation (International Agency for Research on Cancer) (2009) CANCERMondial. Available at www-dep.iarc.fr/, accessed 10 August 2009

European Medicines Agency (2002) ICH Topic E 6 (R1)—Guideline for good clinical practice. Available at www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ich/013595en.pdf, accessed 10 August 2009

Dormandy J, Bhattacharya M, van Troostenburg de Bruyn AR (2009) Safety and tolerability of pioglitazone in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes: an overview of data from PROactive. Drug Saf 32:187–202

Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H et al (2009) Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes in oral agent combination therapy for type 2 diabetes (RECORD): a multicentre, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 373:2125–2135

Rosenstock J, Park G, Zimmerman J (2000) Basal insulin glargine (HOE 901) vs NPH insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes on multiple daily insulin regimens. U.S. Insulin Glargine (HOE 901) Type 1 Diabetes Investigator Group. Diabetes Care 23:1137–1142

Pieber TR, Eugene-Jolchine I, Derobert E (2000) Efficacy and safety of HOE 901 vs NPH insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes. The European Study Group of HOE 901 in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 23:157–162

Home PD, Rosskamp R, Forjanic-Klapproth J, Dressler A (2005) A randomized multicentre trial of insulin glargine compared with NPH insulin in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 21:545–553

Schober E, Schoenle E, van Dyk J, Wernicke-Panten K (2002) Comparative trial between insulin glargine and NPH insulin in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 15:369–376

Ratner RE, Hirsch IB, Neifing JL, Garg SK, Mecca TE, Wilson CA (2000) Less hypoglycemia with insulin glargine in intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes. U.S. Study Group of Insulin Glargine in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 23:639–643

Raskin P, Klaff L, Bergenstal R, Halle JP, Donley D, Mecca T (2000) A 16-week comparison of the novel insulin analog insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH human insulin used with insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 23:1666–1671

Murphy NP, Keane SM, Ong KK et al (2003) Randomized cross-over trial of insulin glargine plus lispro or NPH insulin plus regular human insulin in adolescents with type 1 diabetes on intensive insulin regimens. Diabetes Care 26:799–804

Ashwell SG, Amiel SA, Bilous RW et al (2006) Improved glycaemic control with insulin glargine plus insulin lispro: a multicentre, randomized, cross-over trial in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 23:285–292

Fulcher GR, Gilbert RE, Yue DK (2005) Glargine is superior to neutral protamine Hagedorn for improving glycated haemoglobin and fasting blood glucose levels during intensive insulin therapy. Intern Med J 35:536–542

Chase HP, Arslanian S, White NH, Tamborlane WV (2008) Insulin glargine vs intermediate-acting insulin as the basal component of multiple daily injection regimens for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 153:547–553

Bolli GB, Kerr D, Thomas R et al (2009) Comparison of a multiple daily insulin injection regimen (basal once-daily glargine plus mealtime lispro) and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (lispro) in type 1 diabetes: a randomized open parallel multicenter study. Diabetes Care 32:1170–1176

HOE 901/2004 Study Investigators Group (2003) Safety and efficacy of insulin glargine (HOE 901) vs NPH insulin in combination with oral treatment in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med 20:545–551

Massi Benedetti M, Humburg E, Dressler A, Ziemen M (2003) A one-year, randomised, multicentre trial comparing insulin glargine with NPH insulin in combination with oral agents in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 35:189–196

Rosenstock J, Schwartz SL, Clark CM Jr, Park GD, Donley DW, Edwards MB (2001) Basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: 28-week comparison of insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH insulin. Diabetes Care 24:631–636

Gerstein HC, Yale JF, Harris SB, Issa M, Stewart JA, Dempsey E (2006) A randomized trial of adding insulin glargine vs avoidance of insulin in people with Type 2 diabetes on either no oral glucose-lowering agents or submaximal doses of metformin and/or sulphonylureas. The Canadian INSIGHT (Implementing New Strategies with Insulin Glargine for Hyperglycaemia Treatment) study. Diabet Med 23:736–742

Fritsche A, Schweitzer MA, Haring HU (2003) Glimepiride combined with morning insulin glargine, bedtime neutral protamine hagedorn insulin, or bedtime insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 138:952–959

Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J (2003) The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 26:3080–3086

Pan CY, Sinnassamy P, Chung KD, Kim KW (2007) Insulin glargine vs NPH insulin therapy in Asian Type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 76:111–118

Eliaschewitz FG, Calvo C, Valbuena H et al (2006) Therapy in type 2 diabetes: insulin glargine vs NPH insulin both in combination with glimepiride. Arch Med Res 37:495–501

Rosenstock J, Sugimoto D, Strange P, Stewart JA, Soltes-Rak E, Dailey G (2006) Triple therapy in type 2 diabetes: insulin glargine or rosiglitazone added to combination therapy of sulfonylurea plus metformin in insulin-naive patients. Diabetes Care 29:554–559

Janka HU, Plewe G, Riddle MC, Kliebe-Frisch C, Schweitzer MA, Yki-Järvinen H (2005) Comparison of basal insulin added to oral agents vs twice-daily premixed insulin as initial insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:254–259

Bretzel RG, Nuber U, Landgraf W, Owens DR, Bradley C, Linn T (2008) Once-daily basal insulin glargine vs thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro in people with type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycaemic agents (APOLLO): an open randomised controlled trial. Lancet 371:1073–1084

Blickle JF, Hancu N, Piletic M et al (2009) Insulin glargine provides greater improvements in glycaemic control vs intensifying lifestyle management for people with type 2 diabetes treated with OADs and 7–8% A1c levels. The TULIP study. Diabetes Obes Metab 11:379–386

Yki-Järvinen H, Kauppinen-Makelin R, Tiikkainen M et al (2006) Insulin glargine or NPH combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes: the LANMET study. Diabetologia 49:442–451

Acknowledgements

This analysis was sponsored by sanofi-aventis. Editorial support was provided through the Global Publications Group of sanofi-aventis.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor undertook the review of the pharmacovigilance database, collected and managed the data and undertook the statistical analyses. The corresponding author had full access to the data, and both authors made the decision to submit for publication.

Duality of interest

Institutions connected with P. D. Home receive funding from sanofi-aventis and other insulin analogue manufacturers in regard of his advisory, educational and research activities, including with insulin glargine. P. Lagarenne is an employee of sanofi-aventis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Home, P.D., Lagarenne, P. Combined randomised controlled trial experience of malignancies in studies using insulin glargine. Diabetologia 52, 2499–2506 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1530-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1530-5