Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of 3-dimensional engineered structural panels (3DESP) made from wood-fiber-based laminated paper composites. Since the existing models for calculating the mechanical behavior of core configurations within sandwich panels are very complex, a new simplified orthogonal model (SOM) using an equivalent element has been developed. This model considers both linear and nonlinear geometrical effects when used to analyze the mechanical properties of 3DESP by transforming repeated elements from a tri-axial ribbed core for bending. Two different conditions were studied in comparison with finite element method (FEM) and I-beam equation. The results showed the SOM was consistent with FEM and the experimental result and were more accurate than the I-beam equation. The SOM considering nonlinear geometric deformation needed more computational effort and was found to match well with a FEM model and had slightly better accuracy compared with the linear SOM. Compared with FEM, the parameters in the linear SOM were easier to modify for predicting point-by-point bending performance. However, while the FEM can provide advanced characteristics of the 3DESP such as strain distribution, the linear SOM provided acceptable deformation accuracy and is proposed for preliminary design with multiple parameters. FEM should be applied for advanced analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The development and application of sandwich panels can be traced back to a boat made by the Egyptians at least 5000 years ago (Troitsky 1976; Sumec 1990), where wooden planks were fastened to a wooden framework. Today, sandwich panels are used for a variety of applications within the building, transportation, decking, packaging, marine and aerospace industries using a variety of materials (Vasiliev et al. 2001; Wei et al. 2013a, b, 2015; Davalos et al. 2001; Sharaf and Fam 2011; Wei and McDonald 2016). Sandwich panel efficiencies are achieved by optimizing geometry and selective placement of materials for the faces and core to obtain optimum strength-to-weight performance characteristics. Marine and aerospace applications have the most demanding performance requirements of strength to weight ratio and use the highest strength materials. Many of these sandwich panels are fabricated using honeycomb construction for the core structure. The honeycomb cores are made from linear strips that are selectively bonded along the length and then pulled open to form a roughly shaped hexagon rib with angle of approximately 0° and 60° from the linear-direction. Thus, the effective hexagon rib alignments are generally 120° apart and the ribs are segmented and not continuous. The hexagonal rib alignment improves stiffness in nearly all planer directions, but the effective stiffness in the primary rib direction is slightly higher due to the double bonded thickness of the original linear ribs.

A tri-axial linear rib core concept is being developed that could be used to provide even more uniform or improved performance in all planer directions (Han and Tsai 2003). In this paper, an alternative method was used to evaluate the tri-axial linear rib core. The tri-axial rib core was designed and fabricated using two sets of interlocking linear ribs. The first set of ribs were double slotted 1/3 the width from either side. The second set of ribs were single slotted 2/3 the width of the rib from one side (Fig. 1) (Li et al. 2013). Using the first set of ribs, double notched, as the main rib orientation, then the second set, 2/3 width notched ribs, were inserted from either the top or bottom sides to create a triangular core design. This core configuration has been shown to be stiffer and stronger than foam and honeycomb core (Evans et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2008a). The size of the equilateral-triangle shown can be modified by adjusting the distance between slots. The geometry of the triangle can be modified to an isosceles triangle by adjusting the distances between slots for the double-slotted rib. This core design provides an ability to alter the rib spacing, orientation, and thickness, thus creating a core with optimum performance.

To better evaluate this core’s basic properties as part of a panel system, this study was initiated to develop a SOM having equivalent constitutive properties. The model can then be used to estimate the mechanical performance of sandwich structures based on laminated plate theory. In a previous study, analytical models were grouped into two categories: exact and equivalent (Chen and Tsai 1996). Exact models are more accurate and generate better specific results than equivalent models, but they are more difficult and time consuming to modify when used for preliminary design analyses. The equivalent models are generally simple and save time for broad design analyses. These equivalent models can be directly incorporated into existing finite element methods (FEM) techniques resulting in equivalent models that provide good initial guidance for behavior with slightly lower accuracy. Recently researchers analyzed the equivalent equilateral triangle element to determine an equivalent modulus for sandwich structures using a relative density approach (Fang et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2008b), but it was only adapted for equilateral triangle core structures. The authors are only aware of analytical models that evaluated the mechanical performance of sandwich panels made from metal or synthetic-fiber composites. There was no known literature using wood-fiber-based composite materials with the tri-axial rib core structure.

The Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) is working to develop 3DESP made from wood-fiber-based composites that have enhanced performance capabilities that could meet the need for new and more demanding applications. For some panels, high-strength, fire-resistance, and water resistance are critical requirements. It may be possible that a phenolic impregnated laminated paper might be sufficient to fill some niche applications at reduced costs compared with panels made of metal faces and synthetic paper honeycomb cores (Li et al. 2013, 2014a, b, 2015, 2016a, b, c).

This paper develops a SOM from an equivalent structural element for tri-axial ribbed core structures. Linear and nonlinear geometrical deformation was estimated using the SOM to predict the mechanical bending performance of 3DESP compared with FEM and simple I-beam equation models. Laminated paper composite material was used to fabricate the tri-axial ribbed core and also used for the top and bottom faces. In a previous study (Li et al. 2013), FEM and simple I-beam equation models were used to estimate the bending performance and failure modes for these 3DESPs. Those models were compared with the experimental panels. The FEM models were able to more accurately predict the actual bending performance, but required extensive time to create the geometric shapes. The simple I-beam equation not only underestimated the deformation of the 3DESPs but also was the furthest from the actual deformation at any given load. However, it was significantly easier to estimate and calculate using a spreadsheet. Similarly, the new SOM is a little more complex than the I-beam geometry, but the core geometry can be transformed using simple input variables of the material properties and core rib dimensions. The tri-axial core transformation was based on its repeated rib geometry. The estimated bending performance characteristics for the 3DESPs were determined using this new SOM by both linear and non-linear deformation considerations and were compared with the experimental data, the FEM model, and the simple I-beam equation.

2 Constitutive equations of materials

For some analyses, orthotropic elastic plate configurations are used to analyze anisotropy within composite panels. Figure 2 shows the orthogonal stresses and their nomenclature for a single-layer plate. For these plate applications, the primary loading conditions can be described by in-plane stresses, σ1, σ2, and τ12. In this study, the out-of-plane stresses had little effect on the bending performance and thus were ignored due to simplification (Daniel and Ishai 1994). According to Hooke’s law, the stress and strain relationship can be used to describe the mechanical properties for an orthotropic single-layer plate for the composite panels.

3 Simplified orthogonal model (SOM)

Based on laminated plate theory, the new model for the tri-axial ribbed core structures was used to design and simulate the mechanical performance of 3DESPs. The model could be used for panels with or without faces for small deflection bending tests. The ribs’ size and angle can be modified for easier design and analysis requirements. The tri-axial ribbed repeated pattern is shown in Fig. 3a. The combined pattern consists of five ribs, one parallel to the X-axis and others are set at some angle from the X-axis. Equivalent rib section dimensions were transformed between the X-axis and Y-axis based on angle θ under the same equivalent lengths, m and n, and core height, b as shown in Fig. 3b. Equivalent rib widths for the different orientations are given by:

where \(a\) is the actual rib width, \(a^{\prime}\) is the equivalent rib width having its cross-section perpendicular to the X-axis and \(a^{\prime\prime}\) is the equivalent rib width having its cross-section perpendicular to the Y-axis. The equivalent parameters for the orthotropic ribs (Fig. 3b), can then be transformed to an equivalent solid element (Fig. 3c). An equivalent moment of inertia, \(I_{X}^{\prime}\) in the Y–Z plane, about the Y-axis was determined substituting the equivalent rib thickness, \(a^{\prime}\). Similarly, the equivalent moment of inertia about the X-axis, \(I_{Y}^{\prime}\), was determined using \(a^{\prime\prime}\). The equivalent moments of inertia were then used to determine the equivalent bending stiffness equation given by:

where \(E_{X}\) and \(I_{X}\), \(E_{X}^{\prime}\) and \(I_{X}^{\prime}\) are the equivalent elastic modulus along the X-axis and using the equivalent moment of inertia for orthotropic ribbed element about the Y-axis and for the equivalent solid. The equivalent elastic modulus \(E_{X}^{\prime}\) can then be determined by:

where n is the width for the equivalent solid that has its cross-sectional element perpendicular to the X-axis, and EX along the X-axis for orthotropic ribbed element is equal to the elastic modulus E1 of the laminated paper rib in Table 1.

Similarly, the equivalent elastic modulus along the Y-axis of the equivalent solid (Fig. 3c), is determined by the ribs aligned along the Y-axis of an orthotropic ribbed element in Fig. 3b, the equivalent bending stiffness equation is then given by:

where \(E_{Y}\) and \(I_{Y}\), \(E_{Y}^{\prime}\) and \(I_{Y}^{\prime}\) are the elastic modulus along the Y-axis and the moment of inertia about the X-axis for the orthotropic ribbed element and for an equivalent solid element. The equivalent solid element width dimension is m. In this model, EY along the Y-axis for orthotropic ribbed element is also equal to the elastic modulus E1 of the laminated paper rib in Table 1.

According to \(E_{X}^{\prime}\) and \(E_{Y}^{\prime}\), the other related parameters are given by (Troitsky 1976; Whitney 1987; Chen and Wang 2007):

where \(\mu_{12}\), \(\mu_{XY}^{\prime}\) and \(\mu_{YX}^{\prime}\) are the Poisson’s ratio for the exact rib material and equivalent Poisson’s ratio for the equivalent solid plate element, respectively. \(G_{XY}^{\prime}\)is the equivalent shear modulus of equivalent solid plate element, and then \(G_{XY}^{\prime}\) is equal to \(G_{YX}^{\prime}\).

From the analysis above, the equivalent related parameters \(E_{X}^{\prime}\), \(E_{Y }^{\prime}\), \(\mu_{XY }^{\prime}\), \(\mu_{YX}^{\prime}\) and \(G_{XY}^{\prime}\) are determined using laminated plate theory to design or simulate the 3DESP.

4 Laminated plate theory for 3DESP

Assuming linear-elastic material properties, the displacements about the neutral plane are given by:

where \(u^{0}\), \(v^{0}\) and \(w^{0}\) are the neutral displacements of the solid plate along the X-, Y-, and Z-axis, respectively. For this preliminary and simplified equivalent model \(\gamma_{zx} = \gamma_{zy} = 0\) and normal strain \(\varepsilon_{z} = 0\) can be assumed for the calculation (Vinson 1999). Then the equation of geometric relationship under elastic mechanics is given by:

where \(\varepsilon^{0} ,\upkappa\) and \(z\). are the strains and curvatures at the neutral plane, and the distance from the origin along the Z-axis, respectively. The displacement matrix equation at the neutral plane of the plates, Eq. 11, is given by:

Laminated plate theory (Daniel and Ishai 1994) was used to describe the equivalent continuous tri-axial plate with or without faces as shown, Eq. 12:

The matrixes of [A], [B] and [D] are determined by Eq. 13:

For 3DESP, the geometry and materials were both symmetrically relative to the mid-plane. Therefore, the coupling stiffness [Bij] = 0. By substituting matrix Eq. 13 into Eq. 12, the matrix for the structural core is given by Eq. 14:

The matrix for the faces is given by Eq. 15:

Stiffness \([A_{c} ]\), \([D_{c} ]\) and \([A_{s} ]\), \(\left[ {D_{s} } \right]\) are the tension–compression rigidity and bending-twisting stiffness of the core or faces, respectively. Based on the accumulated principle, the total tension–compression rigidity [A] and bending-twisting stiffness [D] of both core and faces are given by:

Then Eq. 12 can be written as given by Eq. 18:

For Eq. 18, the inverse matrix equation is obtained for calculating the strains and displacements.

According to different boundary conditions, using the inverse matrix of Eq. 18 in conjunction with Eq. 11, the estimated mechanical properties can be determined based on either displacement or stress of the tri-axial core with or without faces.

5 Material properties and test configurations for experimental panels

5.1 Materials properties

The material properties for individual components are provided in Table 1. Phenolic impregnated laminated paper NP610, Norplex-Micarta Inc. (Postville, IA, USA), was used for the faces and the core. The laminated paper had orthogonal properties designated as machine direction (MD) or X-axis and cross-machine direction (CD) or Y-axis. US Composites (West Palm Beach, FL, USA) epoxy, 635, with a ratio of epoxy to hardener at 3:1 was used to bond the faces to the core. Laminated paper in-plane tensile and shear properties and Poisson’s ratios υxy and υxz were obtained from tensile tests according to ASTM D638 (2010) (Table 1).

5.2 Experimental panels

Two 3DESPs were fabricated and tested using a four-point bending test set-up. The MD of the laminated paper was aligned with the longitudinal direction. The panels were tested according to ASTM D393 (2000). The panel dimensions and test set-up information are listed in Table 2.

6 Modeling

6.1 Linear simplified orthogonal model

The new SOM considered linear geometrical change was used to analyze bending for the 3DESP. For bending of symmetric laminates, the constitutive relations reduce to the form shown in Eq. 19:

In-plane bending was assumed, thus:

Using matrix Eq. 11 and Eq. 19 in conjunction with Eq. 20, the curvature along the X-axis is given by:

where:

The shear deformation in the core was ignored when estimating the maximum beam deflection, because the ratio of span to thickness for the panels was larger than 20 so shear in the core should have had little effect on the deflection of the beam. According to the principle of superposition on maximum deflection (Sun 2002), the simply supported panel beam under four point bending test can be calculated using Eq. 23:

where, \(W\) is the panel width. The other parameters are listed in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 4.

6.2 Nonlinear simplified orthogonal model

There are two significant sources of nonlinear bending behavior. One is caused by the nonlinear material properties. Wood or wood-fiber-based materials are viscoelastic materials with high variations. In this paper, a linear-elastic material assumption was used in the simplified model for preliminary analyses. Another source for nonlinear behavior is geometrical. This characteristic is important for large deformational systems. Since the higher order derivative for deflection was neglected in the linear model, a SOM that considered nonlinear geometrical behavior was presented to determine its impact on the panel’s deformation predictions. Nonlinear bending has been widely discussed by many researchers. Nonlinear moment–curvature relationship is one of the significant methods used for bending that does not involve stretching (Nishawala 2011; Wang 1968, 1969). A method was presented by Conway (1947) for large beam deflection with a concentrated load. In that paper and this one, it was assumed that the support using roller configuration has a small horizontal displacement without stretching, then the numerical model based on moment–curvature relationship was applied to calculate the large deflection of sandwich beams (Wang 1968). The equation is given by:

where \(d\upphi /d{\text{s}}\) is the derivative of slope of the beam.

According to the geometry, \(cos\varphi = d{\text{x}}/d{\text{s}}\), multiplying \(d{\text{x}}\) in both sides and integrating the formula of Eq. 24 between any two limits, e and f, then the equation can be written by:

where x is the horizontal distance from support to the moment section. The beam can be divided into several equal intervals to calculate the bending slope. A trial-and-error method was performed to obtain the solution \(\varphi\) for the simply supported beam under a concentrated load (Wang 1968). At first, an initial value for \(\varphi\) at the support point was assumed, and then the other slope can be calculated by Eq. 25. Substituting the computed values to the following Eq. 26 until the solution \(\omega\) approaches 0 using Simpson’s rule (Fertis 2006), then the equation is given by:

where, \(\omega\) is the deflection and c is the horizontal length of beam after deformation.

Then the maximum deflection at mid-span point can be calculated by the slopes as follows:

where y is the deflection on the transverse direction.

Based on the principle of superposition, the simply supported panel beam under four point bending test can be calculated by Eq. 28:

where p is concentrated load number.

The comparison between the linear and nonlinear models using non-dimensional parameters is shown in Fig. 5. It shows that the linear and nonlinear models have no noticeable differences with the small deformation phase. As the load increases, the slope of the nonlinear model decreases while the linear model holds a constant value. The nonlinear model was more accurate, especially, for large deflection for structures made from non-linear material.

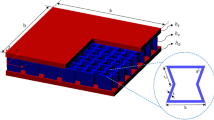

6.3 FEM model

ANSYS FEM software was used to model the 3DESPs (Fig. 6). Material properties and dimensions for the models were the same as those used for the experimental panels and the equivalent model listed in Table 2. The 3D eight-node shell element, Shell 99, was used to analyze the structure. Approximately 20,000 elements were used to mesh the models. The reaction points were held in-place and the load was applied at the same location as the experimental 3DESPs. The mid-point deflection versus load was determined according to the experiments.

6.4 Simple I-beam model

Conventional I-beam model was used to estimate the deflection of the 3DESP in 4-point bending (Sun 2002). The modulus of elasticity E, for the panel, was the E 1 from Table 1. The moment of inertia, I, was simplified and calculated for only the two faces and three axial ribs. The off-axis ribs were not considered in the calculation for I.

The analyses of bending failure load were discussed in a previous paper (Li et al. 2013). In this study, several different linear models and a non-linear model for the 3DESPs in four-point bending were comparatively analyzed by the relationship between load and deflection.

7 Results and discussion

Figure 7 shows the relationship between load and deflection for the linear equivalent, nonlinear equivalent, FEM, and simple I-beam models compared with the experimental panel 1 test data. They show that the load–deflection estimates for all the models were consistent with the experimental data until the panel started to deform in the non-linear phase at around 4.5 kN. At this load, the linear SOM, nonlinear SOM and FEM models were within 5.5, 2.4, and 3.0% error of the experimental panel results, respectively. The simple I-beam model had a 17% error at 4.5 kN. The simple I-beam model did not include the off-axis ribs thus resulting in a lower estimate than the experimental data. Comparing the nonlinear SOM with the FEM model had slightly higher accuracy than the linear SOM. The maximum failure load was 7.0 kN and the panel began to yield around 63% of the maximum load. While the FEM model provided stress distributions throughout the panel and can be used to simulate the performance as an exact model (Li et al. 2013), however, the FEM model set-up required more detail inputs that are much more time consuming than the linear SOM and simple I-beam models. The nonlinear SOM deformation would have better accuracy for large deformation analyses, but for small loads and deformation the differences between models would not have noticeable differences in deformation. The nonlinear SOM would provide better predictions for flexible thin structures. The linear SOM deformation provided a simplified approach and flexibility to modify some parameters for initial design with accuracy within 2.5% of the FEM model predicted deformation at the same load. The simple I-beam theory can roughly evaluate the mechanical performance of a panel, but it loses some accuracy of approximately 11.0% from the experimental values at failure load.

Figure 8 plots experimental panel 2 load and deflection as well as for the linear and nonlinear SOM, FEM, and simple beam models. Panel 2 dimensions were slightly different to those for panel 1, see Table 2. The maximum failure load was 9.9 kN and the panel began to yield around 60% of the maximum load. It also shows that the load–deflection estimates for both the linear and nonlinear SOM and FEM models had similar results as shown for panel 1 until the panel started to deform into the non-linear phase around 6.0 kN. The linear and nonlinear SOM and FEM models were within −0.8, 0.5, and 1% error compared with the experimental panel results at the yield load, while the simple beam model was 15.2% lower than the experimental results. Because of the nonlinear geometrical consideration, the nonlinear SOM and FEM models had slightly higher accuracy than the linear SOM at failure load, but need more computational effort. The difference between the models and experimental result was the nonlinear deformation caused by the nonlinear materials effect.

Failure criterion analysis for these panels was explained in the previous paper (Li et al. 2013). Maximum stress obtained from material properties was used to evaluate the bending failure load of panels for each model. The predicted failure loads for the FEM were performed in both SOMs, linear and nonlinear, and I-beam model for the comparison. For panel 1, the predicted failure loads for the SOM models, FEM model and I-beam model were 8.0 kN. For panel 2, the predicted failure loads for the SOMs, FEM model and I-beam model were 10.7 kN. Compared with the experimental results, both the SOMs and FEM models were more accurate than the I-beam model. It is believed the improvement in prediction was due to the orthogonal core material’s inclusions of the influence of shear and the cross ribs into the core properties that was not easily considered in an I-beam model. Both SOM, linear and nonlinear models can be calculated using EXCEL sheet, and nonlinear SOM had better accuracy, however, it was more complex with many calculating effort.

8 Preliminary design of tri-axial core

The exact representation of the tri-axial core for the sandwich panel is complex for preliminary design needs. The repeatable elements in the core have variable factors such as rib length, rib thickness, and angle that can be transformed into equivalent orthogonal elements represented as a solid layer for laminated plate theory. Analyzing the orthogonal element for the tri-axial core using variable factors such as rib length dimension and angle between the ribs are shown in Figs. 9, 10, and 11.

Figure 9 shows the relationship between the variable angle and orthogonal properties of elastic modulus on X-axis and Y-axis, and shear modulus for the tri-axial ribbed structural core, respectively. The base length of the tri-axial grid and rib section was fixed. The only variable was the angle between two ribs. In Fig. 9, the elastic modulus along the X-axis decreased with an increase in angle from 10° to 80°. The elastic modulus along the Y-axis slowly increased in this range. The two moduli in the X and Y directions were similar when the rib angle was 60°, as expected. The tri-axial core becomes the iso-grid structural core at 60°. The in-plane shear modulus increases from a minimum of 78 MPa to a maximum of 182 MPa at a rib angle of 50°.

Figure 10 shows the relationship between a fixed triangular perimeter and orthogonal properties of elastic modulus along the X-axis and Y-axis, and in-plane shear modulus of tri-axial ribbed core, respectively. The triangular perimeter was set at 352 mm similar to the experimental panels, and the perimeter can be modified for analyses by the same method. In Fig. 10, the perimeter was set but the angle was variable, the elastic modulus along the X-axis decreased having a quadratic trend similar to the elastic modulus along the X-axis for the constant fixed base length of Fig. 9. In contrast, the elastic modulus along the Y-axis slowly increased and intersects with the elastic modulus along the X-axis at 60°, then continues to increase above 60°, the elastic modulus along the Y-axis increases significantly as it approaches theoretical 90° or solid material in the Y-direction. The shear modulus has a slight variance between 53 MPa to 156 MPa as the angle increases from 10° to 80°. Maximum shear modulus is at 40°.

Figure 11 shows the orthogonal properties for elastic modulus and in-plane shear modulus of the core for an equilateral triangular as side length varies. According to the iso-grid structure, the elastic modulus is the same along the X-axis and the Y-axis. Figure 11, shows that the elastic modulus and shear modulus decreased as length increases. These curves show the potential and relative changes that occur for the estimated elastic moduli and shear modulus for different tri-axial core configurations. These analyses could be applied to initial design phases when developing a structural core with or without faces.

9 Conclusion

In this paper, a SOM using laminated plate theory was developed for 3DESP cores. Comparisons were carried out to validate the analytical results. The orthogonal moduli and shear modulus developed for the engineerable tri-axial core can be easily modified based on variable core parameters. Examples of variable options and the resulting material properties were shown using the SOM that could then be applied for further design of 3DESP.

The comparative results showed the SOM of an orthogonal core for 3DESP considering linear deformation exhibits acceptable accuracy and capability to evaluate the initial deformation of 3DESP with minimal input time and effort. The nonlinear deformation model had slightly better accuracy, but required more computational effort. FEM models provide more advanced characterization such as buckling and localized stress distribution information, it requires significantly more time to input multiple parameters to solve complex structural interactions. The simple I-beam equation only considers linear ribs in one direction and does not consider any cross-rib influences for the core and was less accurate in predicting actual performance. In this sense, the preliminary design of a SOM considering linear deformation for 3DESP is the best first approach followed by using the FEM method to validate specific design performance. In addition, a non-orthogonal structural core with variable factors can be easily changed and analyzed by the SOM. The results show the potential and relative changes of elastic moduli and shear modulus for different tri-axial core configurations, which can be applied during an initial design of 3DESP for specific requirements.

The deformation of the new SOM is based on laminate plate theory that can also be satisfied for the wood-fiber-based sandwich structures made from different materials and configurations. The parameters of the material properties and thicknesses for each layer can be modified based on specific application, and then used to predict performance or conduct initial analyses for various parameters during the design process. In the future, an advanced model based on core shear deformation of 3DESP will be studied.

References

ASTM D393 (2000) Standard test method for flexural properties of sandwich constructions. American Society for Testing Materials (ASTM), West Conshohocken

ASTM D638 (2010) Standard test method for tensile properties of plastics. American Society for Testing Materials (ASTM), West Conshohocken

Chen HJ, Tsai SW (1996) Analysis and optimum design of composite grid structures. J Compos Mater 30(4):503–534

Chen Z, Wang BG (2007) Elastic equivalent model of complex fiber reinforced plastic pavement deck. J Chang’an Univ 27(5):24–29

Conway HD (1947) The large deflection of simply supported beams. Philos Mag 38:905–911

Daniel IM, Ishai O (1994) Engineering mechanics of composite materials. Oxford University Press, New York

Davalos JF, Qiao PZ, Xu XF, Robinson J, Barth KE (2001) Modeling and characterization of fiber-reinforced plastic honeycomb sandwich panels for highway bridge applications. Compos Struct 52:441–452

Evans AG, Hutchinson JW, Fleck NA, Ashby MF, Wadley HNG (2001) The topology design of multifunctional cellular metals. Prog Mater Sci 46:309–327

Fang DL, Zhang YH, Chui XD (2009) Mechanical properties and optimal design of lattice structures. Science Press, Beijing

Fertis DG (2006) Nonlinear structural engineering with unique theories and methods to solve effectively complex nonlinear problems. Springer, Berlin

Han DY, Tsai SW (2003) Interlocked composite grids design and manufacturing. J Compos Mater 37:287–316

Li JH, Hunt JF, Cai ZY, Zhou XY (2013) Bending analyses for 3D engineered structural panels made from laminated paper and carbon fabric. Composites Part B 53:17–24

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2014a) High strength wood-based sandwich panels reinforced with fiberglass and foam. Bioresources 9(2):1898–1913

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2014b) Wood-based tri-axial sandwich composite materials: design, fabrication, testing, modeling and application. In: CAMX at Orlando, FL

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2015) Fatigue behavior of wood-fiber-based tri-axial engineered sandwich composite panels (ESCP). Holzforschung 70(6):567–675

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2016a) Simplified analytical model and balanced design approach for modeling light-weight wood-based structural panel in bending. Compos Struct 136:16–24

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2016b) Improved fatigue performance for wood-based structural panels using slot and tab construction. Composites Part A 82:235–242

Li JH, Hunt JF, Gong SQ, Cai ZY (2016c) Testing and evaluation of a slot and tab construction technique for light-weight wood-based structural panels under bending. J Test Eval 44(1):1–10

Nishawala VV (2011) A study of large deflection of beams and plates. Dissertation, State University of New Jersey

Sharaf T, Fam A (2011) Experimental investigation of large scale cladding sandwich panels under out-of-plane transverse loading for building applications. J Compos Constr 13(3):422–430

Sumec J (1990) Regular lattice plates and shells. Elsevier Scientific, Amsterdam

Sun XF (2002) Material mechanics. Higher Education Publishing House, Beijing

Troitsky MS (1976) Stiffened plate: bending, stability and vibrations. Elsevier Scientific, Amsterdam

Vasiliev VV, Barynin VA, Rasin AF (2001) Anisogrid lattice structures survey of development and application. Compos Struct 54:361–370

Vinson JR (1999) The behavior of sandwich structures of isotropic and composite materials. Technomic Publishing Company, Lancaster

Wang TM (1968) Nonlinear bending of beams with concentrated loads. J Frankl Inst 285(5):386–390

Wang TM (1969) Non-linear bending of beams with uniformly distributed loads. Int J Nonlinear Mech 4:389–395

Wei L, McDonald AG (2016) A review on grafting of biofibers for biocomposites. Materials 9(4):303

Wei L, McDonald AG, Freitag C, Morrell JJ (2013a) Effects of wood fiber esterification on properties, weatherability and biodurability of wood plastic composites. Polym Degrad Stab 98(7):1348–1361

Wei X, Tran P, De Vaucorbeil A, Ramaswamy RB, Latourte F, Espinosa HD (2013b) Three-dimensional numerical modeling of composite panels subjected to underwater blast. J Mech Phys Solids 61(6):1319–1336

Wei L, Stark NM, McDonald AG (2015) Interfacial improvements in biocomposites based on poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) and poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) bioplastics reinforced and grafted with α-cellulose fibers. Green Chem 17(10):4800–4814

Whitney JM (1987) Structural analysis of laminated anisotropic plates. Technomic Publishing Company, Lancaster

Zhang YH, Qiu XM, Fang DN (2008a) Mechanical properties of two novel planar lattice structures. J Mech Phys Solids 45(13):3751–3768

Zhang YH, Fan HL, Fang DN (2008b) Constitutive relations and failure criterion of planar lattice composites. Compos Sci 68:3299–3304

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Hunt, J.F., Gong, S. et al. Orthogonal model and experimental data for analyzing wood-fiber-based tri-axial ribbed structural panels in bending. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 75, 5–15 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-016-1119-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-016-1119-x