Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and causes of cardiac arrests related to anesthesia.

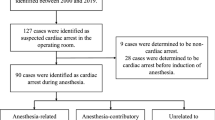

Methods: All patients undergoing anesthesia over a six year period were included in a prospective study. The cardiac arrests encountered during anesthesia and the first twelve postoperative hours in the PACU or ICU were analysed. For each arrest, partially or totally related to anesthesia, the sequence of events leading to the accident was evaluated.

Results: Eleven cardiac arrests related to anesthesia were identified among the 101,769 anesthetic procedures (frequency: 1.1/10,000 [0.44–1.72]). Mortality related to anesthesia was 0.6/10,000 [0.12–1.06]. Age over 84 yr and an ASA physical status >2 were found to be risk factors of cardiac arrest related to anesthesia. The main causes of anesthesia related cardiac arrest were anesthetic overdose (four cases), hypovolemia (two cases) and hypoxemia due to difficult tracheal intubation (two cases). No cardiac arrests due to alveolar hypoventilation were noted during the postoperative periods in either PACU or ICU. At least one human error was noted in ten of the eleven cardiac arrests cases, due to poor preoperative evaluation in seven. All cardiac arrests totally related to anesthesia were classified as avoidable.

Conclusion: Efforts must be directed towards improving preoperative patient evaluation. Anesthetic induction doses should be titrated in all ASA 3 and 4 patients. The prediction of difficult tracheal intubation, and if required, the use of awake tracheal intubation techniques, should remain a priority when performing general anesthesia.

Résumé

Objectif: Le but de cette étude était d’évaluer la fréquence et les causes des arrêts cardiaques liés à l’anesthésie (ACA).

Méthode: Toutes les anesthésies effectuées pendant six ans dans un département d’anesthésie ont été relevées de manière prospective. Les arrêts cardiaques notés en peropératoire et dans les 12 premières heures postopératoires en salle de réveil ou en réanimation ont été analysés. Pour chaque arrêt cardiaque lié partiellement ou totalement à l’anesthésie, l’étude des causes de l’accident était réalisée.

Résultats: Onze ACA ont étés relevés sur 101769 anesthésies éffectuées (fréquence de 1.1/10000 [0.44–1.72]). La mortalité liée â l’anesthésie était de 0.6/10000 [0.12–1.06]. Un âge de plus de 84 ans et un score ASA supérieur à 2 étaient des facteurs de risque de survenue d’ACA. Les principales causes d’ACA étaient le surdosage anesthésique (quatre cas), l’hypovolémie (deux cas) et l’hypoxie par difficulté d’intubation trachéale (deux cas). Aucun ACA hypoxique postopératoire n’était relevé en salle de réveil ou en réanimation. Dans dix des onze ACA au moins, une erreur humaine était relevée, le plus souvent (sept cas) il s’agissait d’une mauvaise évaluation préopératoire. Tous les arrêts cardiaques totalement liés à l’anesthésie étaient classés évitables.

Conclusion: Une meilleure évaluation préopératoire semble primordiale. Chez les patients âgés et/ou avec un score ASA supérieur à 2, un titrage de la dose d’induction est indispensable. La prédiction d’une intubation difficile et, si nécessaire, l’utilisation des techniques d’intubation trachéale vigiles, doivent rester une priorité au cours d’une anesthésie générale.

Article PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

References

Keenan RL, Boyan CP. Cardiac arrest due to anesthesia. A study of incidence and causes. JAMA 1985; 253: 2373–7.

Tiret L, Desmonts JM, Hatton F, Vourc’h G. Complications associated with anaesthesia — a prospective survey in France. Can Anaesth Soc J 1986; 33: 336–44.

Lunn JN, Delvin HB. Lessons from the confidential enquiry into perioperative deaths in three NHS regions. Lancet 1987; 12: 1384–6.

Olsson GL, Hallén B. Cardiac arrest during anesthesia. A computer aided study in 250 543 anaesthetics. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1988; 32: 653–64.

Aubas S, Biboulet Ph, Daurès JP, du Cailar J. Incidence and aetiology of cardiac arrests occurring in operating and recovery rooms during 102,468 anaesthetics. (French) Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 1991; 10: 436–42.

Tikkanen J, Hovi-Viander M. Death associated with anaesthesia and surgery in Finland in 1986 compared to 1975. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995; 39: 262–7.

Warden JC, Horan BF. Deaths attributed to anaesthesia in New South Wales 1984–1990. Anaesth Intensive Care 1996; 24: 66–73.

Standards and Guidelines. American Society of Anesthesiologists 1999 Directory of Members 64th ed. Park Ridge, IL: ASA Ed, 462–76.

Les référentiels en Anesthésie-Réanimation. Société Française d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation. Paris: Elsevier Ed, 1997.

Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Kitz RJ. An analysis of major errors and equipment failures in anesthesia management: considerations for prevention and detection. Anesthesiology 1984; 60: 34–42.

Harrison GG. Deaths attributable to anaesthesia. A 10-year survey (1967–1976). Br J Anaesth 1978; 50: 1041–6.

Pedersen T, Johansen SH. Serious morbidity attributable to anaesthesia. Considerations for prevention. Anaesthesia 1989; 44: 504–8.

Keats AS. Anesthesia mortality in perspective. Anesth Analg 1990; 71: 113–9.

Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1990; 72: 828–33.

Tinker JH, Dull DL, Caplan RA, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Role of monitoring devices in prevention of anesthetic mishaps: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1989; 71: 541–6.

Eichhorn JH. Prevention of intraoperative anesthesia accidents and related severe injury through safety monitoring. Anesthesiology 1989; 70: 572–7.

From RP, Pearson K, Tinker JT. Did monitoring standards influence outcome? (Letter) Anesthesiology 1989; 71: 808–9.

Benumof JL. Management of the difficult adult airway. Anesthesiology 1991; 75: 1087–110.

Rosenblatt WH, Wagner PJ, Ovassapian A, Kain ZN. Practice patterns in managing the difficult airway by anesthesiologists in the United States. Anesth Analg 1998; 87: 153–7.

Auroy Y, Narchi P, Messiah A, Litt L, Rouvier B, Samii K. Serious complications related to regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1997; 87: 479–86.

Biboulet Ph, Capdevila X, Aubas P, Rubenovitch J, Deschodt J, d’Athis F. Causes and prediction of maldistribution during continuous spinal anesthesia with isobaric or hyperbaric bupivacaine. Anesthesiology 1998; 88: 1487–94.

Biboulet Ph, Deschodt J, Aubas P, Vacher E, Chauvet Ph, d’Athis F. Continuous spinal anesthesia: does low-dose plain or hyperbaric bupivacaine allow the performance of hip surgery in the elderly? Reg Anesth 1993; 18: 170–5.

Brown DL, Ransom DM, Hall JA, Leicht CH, Schroeder DR, Offord KP. Regional anesthesia and local anesthetic-induced systemic toxicity: seizure frequency and accompanying cardiovascular changes. Anesth Analg 1995; 81: 321–8.

Gaba DM, Maxwell M, DeAnda A. Anesthetic mishaps: breaking the chain of accident evolution. Anesthesiology 1987; 66: 670–6.

Arnstein F, Catalogue of human error. Br J Anaesth 1997; 79: 645–56.

Helmreich RL, Davies JM. Anaesthetic simulation and lessons to be learned from aviation (Editorial). Can J Anaesth 1997; 44: 907–12.

Sigurdsson GH, McAteer E. Morbidity and mortality associated with anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 1057–63.

Gaba DM, DeAnda A. The response of anesthesia trainees to simulated critical incidents. Anesth Analg 1989; 68: 444–51.

Doyle DJ, Arellano R. The Virtual Anesthesiology™ Training Simulation System. Can J Anaesth 1995; 42: 267–73.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Biboulet, P., Aubas, P., Dubourdieu, J. et al. Fatal and non fatal cardiac arrests related to anesthesia. Can J Anesth 48, 326–332 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03014958

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03014958