Abstract

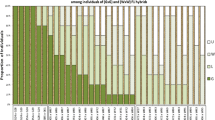

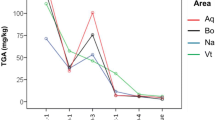

Tuber tissues of 123 commercial cultivars were tested for their ability to synthesize solamarine glycoalkaloids. Eleven cultivars including ‘Kennebec’ and ‘White Rose’ synthesized major concentrations of solamarines, ranging between 42 and 85% of total glycoalkaloid, when tuber slices were exposed to light during wound-healing. Tuber tissues of the other 112 cultivars did not synthesize solamarines, or they synthesized only trace concentrations of these unusual glycoalkaloids.

Nine of the 11 solamarine-synthesizing cultivars have a common ancestor, USDA 96-56. This parental clone synthesizes major solamarine concentrations and it also carries the R1 gene for late blight resistance that it inherited fromSolatium demissum. Results of solamarine analyses of foliage from 47 USDA 96-56 selfed progeny suggest that this parental clone is the source of a major gene(s) for solamarines present in 9 of the commercial cultivars. However, there appeared to be an alternative source of a gene(s) for solamarines because ‘White Rose’, with onlyS. tuberosum ancestors, also synthesized major solamarine concentrations.

There was no association between the R1 gene for late blight resistance and the ability to synthesize solamarines in 31 USDA 96-56 selfed progeny that were analyzed for both characters.

Resumen

Se probó el tejido de tubérculos de 123 variedades comerciales por su capacidad de sintetizar los glicoalcaloides solamarina. Once variedades, incluyendo “Kennebec” y “White Rose,” sintetizaron concentraciones mayores de solamarina que fluctuaron entre 42 y 85% de glicoalcaloide total cuando cortes de tubérculos fueron expuestos a la luz durante la cicatrizatión a las heridas. Tejidos de tubérculos de las otros 112 variedades no sintetizaron solamarinas, o lo hicieron en concentraciones extremadamente bajas de estos glicoalcaloides poco comunes.

Nueve de las 11 variedades que pueden sintetizar solamarinas tienen el mismo progenitor, USDA 96-56. Este clon paternal sintetiza concentraciones mayores de solamarina y también lleva en gene R1 para resistencia a tizón tardío heredado deSolanum demissum. Resultados de solamarinas analizados de follaje de 47 progenies obtenidos por autofecundación del clon USDA 96-56 indican que este clon paternal es la fuente de un gene o genes majores para los solamarinas presentes en nueve de las variedades comerciales. Sin embargo, parece que hay una fuente alternativa de un gene (o genes) mayores para solamarina porque “White Rose,” que tiene solamente S. tuberosum como ancestros, también sintetiza concentraciones majores de solamarina.

No hubo asociación entre el gene R, para tizón tardío y la capacidad de sintetizar solamarina en 31 progenies obtenidos por autofecundación del clon USDA 96-56 que fueron analizadas por ambos caracteres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Anonymous. 1959. Keswick. p. 29. In: Potato handbook: potato varieties issue. Vol. IV. Am Potato Assoc, Orono, ME.

Black, W. 1952. Inheritance of resistance to blight (Phytopthora infestons) in potatoes: inter-relationships of genes and strains. Proc Royal Soc Edin B64: 312–352.

Brown, D. and R. R.Keeler. 1978. Structure-activity relation of steroid teratogens. 3. Solanidan epimers. J Agric Food Chem 26:566–569.

Clark, C. F. and P. M. Lombard. 1946. Descriptions of, and key to American potato varieties. USDA Circ No 741, April 1946, 50 pps.

Emanuel, I. and L. E. Sever. 1973. Questions concerning the possible association of potatoes and neural-tube defects, and alternative hypothesis relating to maternal growth and development. Teratology 8:325–333.

Grechushnikov, A. I. 1955. [Changes in composition of glycoalkaloids in interspecific hybrids ofS. demissum X S. tuberosum.] Fiziol Rast (Mosc.) 2:476–82. (Chem Abstr 50:2757).

Gregory, P., S. L. Sinden, S. F. Osman, and W. M. Tingey. 1980. Glycoalkaloids of some wild potato tuber-bearing Solanum species. J Agric Food Chem (In press).

Keeler, R. F., D. Brown, D. R. Douglas, G. F. Stallknecht, and S. Young. 1976. Teratogenicity of the solanum alkaloid solasodine and of ‘Kennebec’ potato sprouts in hamsters. Bull Environ Contain Toxicol 15:522–524.

Keeler, R. F., S. Young, and D. Brown. 1976. Spina bifida, exencephaly and cranial bleb produced in hamsters by the solanum alkaloid solasodine. Rev Comm Chem Pathol Pharmacol 13:723–730.

Lauer, F. I. 1959. Recovery of recurrent parent characters from crosses ofSolanum demissum XS. tuberosum in successive backcrosses. Am Potato J 36:345–357.

McCollum, G. D. and S. L. Sinden. 1979. Inheritance study of tuber glycoalkaloids in a wild potato,Solatium chacoense Bitter. Am Potato J 56:95–111.

Muller, K. O. 1951. [The Origin and history of the W-varieties, and their role in potato breeding.] Z Pflanzenzuecht 29:366–387.

Nishie, K., W. P. Norred, and A. P. Swain. 1975. Pharmacology of α -chaconine and α-tomatine. I. Toxicological and teratological studies. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 12:657–667.

Osman, S. F. and S. L. Sinden. 1977. Analysis of mixtures of solanidine and demissidine glycoalkaloids containing identical carbohydrate units. J Agric Food Chem 25:955–957.

Schreiber, K. 1963. [Glycoalkaloids of tuber bearingSolanum species.] Kulturpflanze 11:422.

Schreiber, K. 1968. Steroid alkaloids: TheSolanum group. Pp. 1–192. In: The Alkaloids, Vol. X, R. H. F. Manske (ed.), Academic Press, New York.

Shih, Min-Jwei and J. Kuc. 1974. α -and β- solamarine in KennebecSolanum tuberosum leaves and aged tuber slices. Phytochemistry (Oxf) 13:997–1000.

Sanford, L. L. and S. L. Sinden. 1972. Inheritance of potato glycoalkaloids. Am Potato J 49:209–217.

Sinden, S. L., L. L. Sanford, and S. F. Osman. 1980. Glycoalkaloids and resistance to the Colorado potato beetle inSolanum chacoense Bitt. Am Potato J 57:331–343.

Twomey, J. A., R. V. Akeley, K. W. Knutsen, and M. Workman. 1968. Oromonte, a chipping potato for Colorado. Am Potato J 45:297–299.

Varns, J., W. Currier and J. Kuc. 1971 Specificity of rhisitin and phytuberin accumulation by potato. Phytopathology 61:968–971.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinden, S.L., Sanford, L.L. Origin and inheritance of solarmarine glycoalkaloids in commercial potato cultivars. American Potato Journal 58, 305–325 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02854097

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02854097