Abstract

Joining or leaving a platform ecosystem is a key strategic decision for software developers. ‘Multi-homing’ is strategy in which a company distributes its products via more than one platform ecosystem in parallel. ‘Single-homing’ is an opposite strategy in which the software is being distributed exclusively via a single platform ecosystem. On one hand, multi-homing can increase customer reach in markets where customers typically single-home. On the other hand, creating a new version of the software product for multi-homing purposes generates, e.g., conversion, maintenance, and marketing cost. Interestingly, multi-homing as a strategic choice in software business has thus far have received surprisingly little academic scrutiny. In particular, there is very little information on whether multi-homing is an economically viable distribution strategy. To fill in this void, we explore the financial performance between single-homers and multi-homers in mobile application ecosystems. We investigate how the decision to multi-home affects firm performance with a sample of mobile application developers. The results imply that the revenue growth has been faster among single-homers while our dataset is biased towards single-homers. This calls for additional research comparing the two distribution strategies. This paper acts as a starting point for a research agenda in order to better understand multi-homing a strategic choice in software business.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Ecosystems and platforms are nowadays core building blocks of business [16]. Whereas terminology in this field is not yet stabilized and some terms are used interchangeably [c.f. 11, 23], we follow the view that a technological platform is a core of an ecosystem that enables its formation [5]. An ecosystem itself consists of a platform and its owner, as well as from complements and their providers, and from customers [8]. Well-known examples of such ecosystems include marketplace-centred mobile application ecosystems (e.g., Apple’s App Store for iOS devices and Google Play for Android operating system devices).

As ecosystems and platforms have become a major distribution channels in software business [14], the decision to single-home or multi-home is a key strategic decision for a large number of software companies. In economic theory, multi-homing refers to participating more than one competing marketplace in parallel [20]. In today’s software development and software business, multi-homing typically means distributing a product via more than one competing platforms such as Android and iOS at the same time whereas single-homing refers to distribution the product via only one platform [4].

As ecosystems typically have entry barriers [19], a multi-homing strategy incurs costs to the software developer. In software ecosystems, typical entry barriers are fees for participation, ecosystem-specific development tools that are not interchangeable or specific skills needed. For example, Google Play features a 25 USD registration fee and an official development tool is Android software development kit (SDK). For App Store, a membership is 99 USD and the official tool is iOS SDK. The iOS SDK and Android SDK are not cross-compatible.

While nowadays there are tools that reduce the costs of cross-platform software development such as Apache Cordova and Titanium [1, 6], multi-homing always generates some additional costs related to e.g. development, maintenance, product management and marketing of a new platform-specific version. Thus, the decision to multi-home a firm’s products to more than one ecosystem requires careful balancing between the potential for gaining a larger market share [22] as well as reducing dependency on a single ecosystem orchestrator [15] against to the increased costs [7].

Against this backdrop, it is surprising that the outcomes of adopting a multi-homing vs. single-homing strategy in terms of software developer’s performance remains largely opaque in software business literature [8]. Most of the extant literature on multi-homing focuses on the ecosystem level analysis while company-investigations of multi-homing as a strategic distribution choice and its outcomes on firm performance remain largely absent. However, choosing between multi-homing and single-homing is a strategic decision for practically any independent software vendor.

As a result, we put forward a fundamental question for software developers: Does it pay off to multi-home?

To shed light into this looming, yet thus far unanswered question, we sampled a set of 10,000 mobile application developers from Apple’s App Store, Google Play and Microsoft’s Windows Phone Store. We then investigated their product offerings to identify the companies that multi-home and acquired their financial information from the ORBIS database. Finally, we compare the turnover growths of 812 mobile application vendors to detect if multi-homing pays off or not.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the second section, we present an overview of prior research on multi-homing in software business. In Sect. 3, we describe the research approach and data collection, followed by the results in the fourth section. In Sect. 5, we discuss the findings, unveil the limitations and put forward suggestion for future research.

2 Multi-homing in Software Platforms

Multi-homing can have a profound effect on platform competition dynamics and thus ultimately the very structure of the entire market [5, 7, 9, 20–22, 24]. With respect to software platforms, in presence of several competing platforms the structure of the market depends on multi-homing patterns of application developers [22]. According to Sun and Tse [22], extensive multi-homing among application developers enables competition between platforms whereas single-homing eventually turns the market towards a single dominant ecosystem.

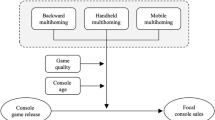

Landsman and Stremersch [18] in turn studied multi-homing in the gaming console market. They showed that initially a multi-homing strategy hurts the sales of the hardware consoles but this effect fades away when the ecosystem ages. Landsman and Stremersch [18] further divided multi-homing into two different categories: (1) Seller-level multi-homing that refers to a situation where the same producer, e.g. application developer works for several ecosystems. (2) Platform-level multi-homing refers to a situation where a developer, or someone else, distributes the same product via several ecosystems.

While the two forms of multi-homing are likely to be correlated, it is also possible that a developer offers different products to different ecosystems — or different developers offer a certain product to different ecosystems. As an example of the latter, the Facebook apps in Google Play and Apple Store were developed by Facebook whereas the Facebook app in Windows Store was developed and published by Microsoft a few year ago.

According to Hyrynsalmi et al. [10], the overall number of multi-homing is small in mobile application markets. However, the most popular applications are available in all competing ecosystems and the producers of these applications largely multi-home [14]. Hyrynsalmi et al. [14] describe this situation as a multi-level two-sided market to underscore the difference between the level of multi-homing in general and multi-homing among the most popular applications.

Despite the theoretical contributions to the areas, empirical studies l assessment remains low. Idu et al. [15] analysed multi-homing inside Apple’s three different sub-ecosystems. The found 17.2% platform-level multi-homing in their set of 1,800 mobile applications. In their empirical analysis of multi-homing in the three leading (Android, iOS, and Windows Phone) mobile application ecosystems, Hyrynsalmi et al. [14] found that only 1.7–3.2% of all applications (i.e. platform-level) and 5.8–7.2% all developers (i.e., seller-level) in the three mobile application operating systems were multi-homing. Interestingly, however, from the most popular applications 41–58% were multi-homing. Similarly, 42–69% of the keystone developers, i.e. producers of the most popular applications, were multi-homing.

Whereas the multi-homing rate is a significantly higher than one showed by Hyrynsalmi et al. [14] it is worth of noting that entry barrier into a different sub-ecosystem inside Apple’s ecosystem is lower (e.g., development tools are same). Furthermore, it should be noted that there are numerous different Android devices while Apple has only a limited number of different iOS phone and tablet versions. In addition, for a comparison, Burkard et al. [3] studied popularity of multi-homing strategy in SaaS business solutions market. They found only 70 multi-homers (ca. 3.5%) in their dataset of over two thousand software vendors.

Nevertheless, the surveys on the popularity of multi-homing strategy shows that often only a small part has adopted the publication strategy. However, it seems that number of adopters are rising. For example, when the results of Hyrynsalmi et al. [14] and Idu et al. [15] are compared against Boudreau’s [2] results, who found less than 1% overall multi-homing rate, a decade earlier in the mobile application markets, a clear growth in the number of multi-homing strategy adopters can be seen. This might be a result of either the growth of mobile application market’s value [c.f. 8], the development of technological tools for multi-homing [c.f. 1] or due to a wider understanding of the platform economy and its rules [c.f. 16].

A number of studies addressing the impacts of multi-homing to a single software company are low. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only one prior study has examined this topic. In a cross-segment approach, Hyrynsalmi et al. [12] analysed multi-homing of Finnish computer game companies. In their study, they included all game companies ranging from mobile game and social media add-ons to AAA class video game developers. Out of the 208 active game companies, they found that a majority (54.8%) were multi-homers. However, they did not found any major differences between multi-homers’ and single-homers’ financial performances.

To summarize, a clear majority of existing work focuses on a market-level analysis and on the impacts of multi-homing to a market as a whole [e.g. 5, 18, 22]. However, there is a dearth of studies addressing how multi-homing affects to individual companies. While there are arguments for and against of using multi-homing publishing strategy [7, 14, 15] and importance of multi-homing to development of whole market [5, 7, 22], it is surprising that there is a little empirical evidence whether is worth or not, for a single developer to multi-home.

Therefore, this study focuses on this question and aims to uncover are there quantitative evidence that multi-homing would be a better choice for a single developer than single-homing strategy. We select mobile application ecosystems as the case environment as it is currently a swiftly developing market with multiple different, non-compatible among each other, operating systems. Furthermore, there is a plethora of application developers, small as well as big ones, joined in the market. Thus, there is a potentially rich information available in the domain.

3 Empirical Research

In this study, we focus on the question whether it pay off or not to multi-home. We chose revenue growth of our focal indicator of the financial viability of multi-homing vs. single-homing. As multi-homing increases the number of potential customers, it should lead to increasing revenues compared to single-homing. As an example, Gartner’s latest reportFootnote 1 states that in the last quarter of 2016, 81.7% of the new smart phones were using Android operating system and 17.9% were using iOS devices. Despite this, it is reported that applications in the Apple’s App Store are generating higher revenue than the ones in Google Play storeFootnote 2,Footnote 3. Thus, for a mobile application developer gain the largest audience, he should select the Android operating system whereas it is likely that higher revenue is generated in Apple’s App Store.

Revenue growth as an indicator does not take into account the increased costs associated to multi-homing. However, as obtaining information about these costs from financial statements is practically impossible, we concluded that revenue growth is an appropriate measure to extrapolate the pay-off of multi-homing.

In this study, we utilized a simple three-steps research process illustrated in Fig. 1. In the first step, to gather the starting data, we employed a web crawler that collected a sample 10,000 mobile application vendors from three mobile application marketplaces, Google Play, Apple’s AppStore and Windows Phone Store. From each vendor, we collected the name that the vendor used to presents itself in the marketplace and the number of applications the vendor has published in that marketplace. We then manually double-checked the data and e.g. in case of slightly different names between the marketplaces matched the data. The dataset and the multi-homing information was collected in the beginning of 2013.

In the second step, to acquire financial information regarding the vendors, we used the ORBIS financial information database by Bureau van Dijk. The ORBIS database contains financial information on over 200 million companies globally. We uploaded the list of 10,000 software vendor names for the batch search and used the database’s matching logic to identify corresponding companies. As the database allows selecting between various levels of matching accuracy, to maximize the quality of our data, we decided to only accepted matches where the matching quality was given the highest ‘A’.

From the 10,000 software vendor names in our query, a match was found for 3,247 (32.5%). As the mobile application developers are known to be a rather heterogeneous set ranging from commercial developers with financial interests to hobbyist and non-profit organizations [13], it was expected that only a minority of the developers would have founded and registered a company for collecting the income and paying taxes from the applications sales.

Our subscription of ORBIS did not cover financial information of 34 companies, and thus those were excluded from performance analyses. From the identified 3,247 companies, there were companies and organizations from various fields. For example, we found several European airports multi-homing, i.e. providing their apps via all marketplaces.

For all companies, we acquired operating revenue information from the years 2013, 2014 and 2015. Naturally, only for a few companies the financial information of the year 2016 have been registered; thus, this year is omitted. The financial performance is studied through the growth of a company’s revenue from the year 2013 to 2014 and 2015. We use three intervals for measuring the performance growth. The reason is that the impact of multi-homing in the revenue of the company might take more than a year. The starting point is 2013 as the multi-homing information of the year 2013 was acquired from the marketplaces.

In the third step of the process, to focus deliberately on companies that are in software business, we added a further constraint to narrow down our results to companies that have defined ‘Information and Communication’ as their main business domain classification. We thereafter omitted companies with missing revenue information. The final set of ICT companies consisted of 538 companies.

4 Results

The identified 3,247 companies are from various fields as shown in Fig. 2. The largest sections in our dataset are ‘Information and Communication’ (808 firms, 30% of all), ‘Wholesale and retail trade’ (440, 16%), and ‘Professional, scientific and technical activities’ (387, 14%). For 200 companies, no information was stored in under the field ‘NACE Rev. 2 main section’. The companies are from 39 different countries while Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany being the biggest country of origin.

The financial indicators are infrequently reported to the database. For example, it is quite common in the dataset that a company might not have any financial indicators stored for a certain year whereas they are available for previous and next years. For example, our full dataset contains financial information of over 3,200 companies. From those, only 1,102 companies have revenue information available for the years 2013 and 2014. Thus, in the forthcoming performance analysis, the number of companies used in each analysis varies.

The average turnover growths for the studied firms are shown in Table 1. When looking our sample of companies as a whole, the average revenue growth rate from 2013 to 2014 was 80 per cent and 2014 to 2015 it was 79 per cent. At the same, the companies in the ICT field growth averagely only 54% and 13%.

We identified 209 (6.4%) companies multi-homing in our set. Out of those, 78 were classified as ICT companies (i.e. belonging NACE Rev. 2 class ‘J – Information and communication’) and 131 into other fields. Thus, 9.6% of ICT companies are multi-homing whereas only 6.2% of non-ICT companies are multi-homers. While ICT companies are more keen to multi-home based than non-ICT companies, the multi-homing rates still remain low.

In the final step of the analysis, we focused on the performance of ICT companies. In this, we excluded non-ICT companies as there are likely more factors explaining their growth of revenue than decision to publish multi-homed application. Thus, here we focus on the 812 companies belonging into ‘Information and communication’ category.

Interestingly, and contrary to our assumptions, the results imply that single-homing ICT companies had stronger growth rates than multi-homers (59% vs. 14% in 2013–2014, 14% vs. 1% in 2014–2015, and 51% vs. 26% in 2013–2015) as depicted in Table 1. While the number of multi-homers remain small in each studied set, they are growing considerably slower than single-homers. The similar phenomenon can be seen also by looking the average growths of all companies – here also single-homing companies outperform multi-homing companies with a reasonable big margin.

To summarize, as Table 1 shows the turnover growth is faster among single-homers than multi-homers during the studied periods. However, the final sample was heavily biased towards single-homers as less than ten per cent of the companies are multi-homing. Furthermore, due the sparse availability of financial information, the number of multi-homing ICT-companies remain remarkable low. This largely inhibits drawing far-reaching conclusions from the data.

5 Discussion

In the following, we will first discuss on the implications of this study. It is followed by a discussion of limitations and some ideas for future work.

5.1 Implications

This study was motivated to shed some empirical light on a key question in software business does it pay off to multi-home? To this end, we concluded an extensive empirical study to identify relevant companies and used the ORBIS financial information database of obtain the relevant financial figures.

While multi-homing is generally considered a desirable strategic choice in prior software business literature [14], based on the findings from this study, we cannot empirically corroborate, or reject, this notion. While our initial results show that single-homers are performing better in the terms of revenue growth, the number of multi-homing companies, with financial information, included into the sample remain too low to draw a statistically reasonable conclusion.

We started by hypothesizing that multi-homing would incur more cost due to the entry barriers as well as the need of maintaining alternative versions. However, a larger potential buyer population would ultimately payback the investments. Our initial results support these hypotheses only weakly, if at all, as the single-homers are collecting remarkably better revenues. In other words, based on this analysis, it seems that multi-homing does not pay off. However, due to the missing financial information and dominance of single-homing companies in our dataset, far-reaching decision cannot be made.

Yet our ultimate research question remains unanswered, our approach in empirically investigating issue is nevertheless a definite contribution to software business literature [c.f. 8, 15] by setting forward the research agenda towards a better understanding of multi-homing as a strategic choice in software business. To this end, our study clearly demonstrates that relying on publically available financial information as the only source of data is not a sufficient approach to investigate the bottom-line financial effect of multi-homing.

From a practice-oriented perspective, while the effect of multi-homing on turnover development remains unanswered, multi-homing remains a viable strategy to reduce software developers’ dependency on a single client platform. Hence, the decision whether to multi-home or not is not solely a matter of maximizing revenue but essentially about managing risks.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research

Like any other piece of empirical research, our study is subject to a number of limitations. First of all, it is evident that our current data is by no means sufficient to provide answer to a pivotal research question such as the one posed in this study. Thus, we strictly advice against drawing far-reaching conclusions from the present study. There are two main reasons for this: (1) Publicly available financial information has remarkable amount of missing fields for all companies, and (2) partially due to the previous reason, the number of multi-homers with reported performance measures remained low for a statistically significant analysis.

As a result, additional research with a new data collection is needed. Furthermore, due to the limitations of the current dataset and the exploratory stance of the study, further studies in the area should control for the potential confounding effects of the various factors that may influence growth rates to meaningfully isolate the potential influence of multi-homing. Nevertheless, we demonstrated a decent sampling strategy for a selection of mobile application vendors that can be turn out to be useful for other kinds of studies.

Alternative option would be to change the research stance from quantitative analysis towards a qualitative work. As this study presents, finding statistically relevant results might be problematic (e.g., the selection of performance measures), thus a qualitative case study on multi-homing and single-homing companies could create a better picture of the benefits and drawbacks of multi-homing publishing strategy.

Finally, in future work, also the type of the market or apps should be reconsidered as they might also play a role in the performance analyses. For example, the console gaming market is mature and relationships within the ecosystem are more complex than in the mobile application markets. Several games are exclusively published for a certain console and only after a delay of months, they are ported to the other consoles. Furthermore, the development of freemium mobile games features its unique characteristics [cf. 17]. Thus incorporating a wider selection of different markets and ecosystems would be an advisable course for future research.

6 Conclusion

The purpose of the paper was to be a starting point for a research agenda in order to better understand multi-homing as a strategic choice in software business. The market tendency either towards multi-homing or single-homing has been linked in the extant theories on the future development of the whole market. However, only little has been research on the impact of multi-homing to companies.

We performed a quantitatively study of over 3,200 companies that had published a mobile application. Single-homing companies (93.6% of all) dominate the set. While only a small amount of them were found to be multi-homers, it seemed that on average single-homers are performing better than multi-homers. However, due to the small amount of multi-homing companies with available financial information, we advice against of doing far-reaching decisions based on this. Nevertheless, this is among to first to address the question do multi-homing pay off to the companies.

Notes

- 1.

Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Grew 7 Percent in the Fourth Quarter of 2016. http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3609817 Accessed May 5th, 2017.

- 2.

App Annie 2015 Retrospective. http://go.appannie.com/report-app-annie-2015-retrospective Accessed May 5th, 2017.

- 3.

App Annie 2016 Retrospective. http://go.appannie.com/app-annie-2016-retrospective Accessed May 5th, 2017.

References

Ahti, V., Hyrynsalmi, S., Nevalainen, O.: An evaluation framework for cross-platform mobile app development tools: a case analysis of Adobe PhoneGap framework. In: Rachev, B., Tegolo, D., Kalmukov, Y., Smrikarova, S., Smrikarov, A. (eds.) Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 2016, pp. 41–48 (2016)

Boudreau, K.: Too many complementors? Evidence on software developers. Technical report hal-00597766, HEC-Paris School of Management (2007). https://hal-hec.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00597766

Burkard, C., Widjaja, T., Buxmann, P.: Software ecosystems. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 4(1), 41–44 (2012)

Caillaud, B., Jullien, B.: Chicken & egg: competition among intermediation service providers. RAND J. Econ. 34(2), 309–328 (2003)

Cusumano, M.A.: Staying Power: Six Enduring Principles for Managing Strategy and Innovation in an Uncertain World (Lessons from Microsoft, Apple, Intel, Google, Toyota and More). Oxford University Press, Oxford (2010)

Dhillon, S., Mahmoud, Q.H.: An evaluation framework for cross-platform mobile application development tools. Softw. Pract. Exp. 45(10), 1331–1357 (2015)

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M.W.: Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Bus. Rev. 84(10), 92–101 (2006)

Hyrynsalmi, S.:. Letters from the war of ecosystems — an analysis of independent software vendors in mobile application marketplaces. TUCS Dissertations No 188. University of Turku, Turku, Finland (2014)

Hyrynsalmi, S., Linna, P.: The role of applications and their vendors in evolution of software ecosystems. In: Biljanovic, P. (ed.) Proceedings of the 40th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics, pp. 1686–1691. IEEE (2017)

Hyrynsalmi, S., Mäkilä, T., Järvi, A., Suominen, A., Seppänen, M., Knuutila, T.: App Store, Marketplace, Play! an analysis of multi-homing in mobile software ecosystems. In: Jansen, S., Bosch, J., Alves, C. (eds.) Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshops on Software Ecosystems, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, CEUR-WS, vol. 879, pp. 59–72 (2012)

Hyrynsalmi, S., Seppänen, M., Nokkala, T., Suominen, A., Järvi, A.: Wealthy, healthy and/or happy — what does ‘ecosystem health’ stand for? In: Fernandes, J.M., Machado, R.J., Wnuk, K. (eds.) ICSOB 2015. LNBIP, vol. 210, pp. 272–287. Springer, Cham (2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-19593-3_24

Hyrynsalmi, S., Suominen, A., Jansen, S., Yrjönkoski, K.: Multi-homing in ecosystems and firm performance: does it improve software companies’ ROA? In: IWSECO 2016 – Proceedings of the International Workshop on Software Ecosystems, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, CEUR-WS, vol. 1808, pp. 56–69 (2016)

Hyrynsalmi, S., Suominen, A., Mäkilä, T., Järvi, A., Knuutila, T.: Revenue models of application developers in android market ecosystem. In: Cusumano, M.A., Iyer, B., Venkatraman, N. (eds.) ICSOB 2012. LNBIP, vol. 114, pp. 209–222. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30746-1_17

Hyrynsalmi, S., Suominen, A., Mäntymäki, M.: The influence of developer multi-homing on competition between software ecosystems. J. Syst. Softw. 111, 119–127 (2016)

Idu, A., van de Zande, T., Jansen, S.: Multi-homing in the Apple ecosystem: why and how developers target multiple Apple App Stores. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems, pp. 122–128. ACM, New York (2011)

Kenney, M., Zysman, J.: The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 32(3), 61–69 (2016)

Koskenvoima, A., Mäntymäki, M.: Why do small and medium-size freemium game developers use game analytics? In: Janssen, M., Mäntymäki, M., Hidders, J., Klievink, B., Lamersdorf, W., van Loenen, B., Zuiderwijk, A. (eds.) I3E 2015. LNCS, vol. 9373, pp. 326–337. Springer, Cham (2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25013-7_26

Landsman, V., Stremersch, S.: Multi-homing in two-sided markets: an empirical inquiry in the video game console industry. J. Mark. 75(6), 39–54 (2011)

McAfee, P., Mialon, H.M., Williams, M.A.: What is a barrier to entry? Am. Econ. Rev. 94(2), 461–465 (2004)

Rochet, J.C., Tirole, J.: Platform competition in two-sided markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 1(4), 990–1029 (2003)

Rochet, J.C., Tirole, J.: Two-sided markets: a progress report. RAND J. Econ. 37(3), 645–667 (2006)

Sun, M., Tse, E.: When does the winner take all in two-sided markets? Rev. Netw. Econ. 6(1), 16–40 (2007)

Suominen, A., Hyrynsalmi, S., Seppänen, M.: Ecosystems here, there, and everywhere. In: Maglyas, A., Lamprecht, A.-L. (eds.) Software Business. LNBIP, vol. 240, pp. 32–46. Springer, Cham (2016). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40515-5_3

Teixeira, J., Hyrynsalmi, S.: How do software ecosystems co-evolve? A view from OpenStack and beyond. In: Ojala, A. (ed.) Software Business: 8th International Conference, ICSOB 2017, pp. 1–15. Springer, Cham (2017)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper

Hyrynsalmi, S., Mäntymäki, M., Baur, A.W. (2017). Multi-homing and Software Firm Performance. In: Kar, A., et al. Digital Nations – Smart Cities, Innovation, and Sustainability. I3E 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10595. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68557-1_39

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68557-1_39

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-68556-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-68557-1

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)