Abstract

Limitations in the current knowledge base on the importance of perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement are visible. Past studies on this topic specifically take place in certain contexts (usually the Western context) using various instruments. The current study aims to extend our understanding of the link between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement based on students’ perceptions using uniform measures across six contrasting national contexts. It also aims to explore the role of certain personal variables in the interplay between students’ perceived teaching behaviour and engagement. In total, 40,788 students in The Netherlands, Spain, Indonesia, South Korea, South Africa, and Turkey participated in the survey using the My Teacher Questionnaire (MTQ) and the Student Engagement scale. Item Response Theory (IRT) and Classical Test Theory (CTT) analyses were used to analyse the student data. Results show that, in general, perceived teaching behaviour is positively related, and mostly strongly, to student engagement across the six educational contexts. This means the higher the perceived teaching behaviour, the higher students reported their academic engagement, and vice versa. Slight differences in the magnitude of relationships between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement are evident. The strongest link was found in the Netherlands, followed by South Korea, South Africa, Indonesia, Turkey, and Spain. Student gender, age, and school subject hardly show effects on the interplay between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Effective teaching behaviour is of key importance for student learning and outcomes (Coe et al., 2014; Hattie, 2009; Muijs et al., 2014). Among other student learning characteristics, student engagement has been recognized as an important predictor of students’ academic performance (Appleton et al., 2008). Student engagement is viewed as the primary theoretical model for promoting school completion characterized by sufficient academic and social skills to contribute in concurrent and subsequent academic success (Christenson et al., 2008; Finn, 2006; Skinner et al., 2008). Furthermore, student engagement has been identified as a powerful mediator between teaching quality and student achievement (Virtanen et al., 2015). Research shows that student engagement is positively associated with various aspects of effective teaching within one educational context (Maulana et al., 2017; Pianta et al., 2012; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2015). Higher levels of engagement are uniquely associated with higher levels of teaching quality (Quin et al., 2017; Wang & Eccles, 2012). Because teacher-student interaction is recognized as a primary source of student development (Pianta & Allen, 2008), understanding the universal link between teaching behaviour and student engagement is a desideratum. This is because social interactions with teachers within the school setting may serve as a protective factor for students who are weakly engaged in learning (Guo et al., 2011).

Despite evidence on the importance of teachers’ teaching quality for student engagement, the current knowledge base is limited in at least three ways. First, most studies on engagement and teaching behaviour have been conducted in the West. Hence, the extent to which the results of Western studies represent non-Western contexts is unclear. Particularly, little is known whether the link between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement differs in magnitude across different educational contexts. Next, it remains unclear whether certain personal (i.e., student gender and age) and contextual (i.e., school subject) factors can explain the differential link between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement in Western and non-Western contexts. Some studies indicate direct links between student gender, age, and school subjects on perceived teaching behaviour or on self-reported engagement separately (e.g., Cohen et al., 2018; Cooper, 2014; Fernández-García et al., 2019; Havik & Westergard, 2020; Lietaert et al., 2015). Identifying potential mediating roles of student gender, age, and school subject in the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement is important to inform more tailored interventions for teaching improvement.

Previous studies on teaching behaviour and student engagement are rather fragmented and are mostly restricted to a single context (e.g., Maulana et al., 2017; Roorda et al., 2011; Virtanen et al., 2015). Although there were studies conducted in non-Western contexts, these were typically published in their own languages and published in local, non-English, journals (e.g., Hidayati & Rodliyah, 2020). Hence, it is largely unknown whether the link between perceived engagement and teaching behaviour, and the role of some background variables, is universal.

Furthermore, past studies typically studied teaching behaviour and student engagement using various instruments. The instruments used in past studies vary, at least to certain degree, concerning their underlying conceptualizations, operationalisations, and modes (observation vs. self-reports). The heterogeneity of the instruments poses challenges for comparing the link between teaching behaviour across contexts more accurately. In addition, research examining the association between student perceptions of teaching behaviour and their perceived engagement across various contexts is scarce (Quin et al., 2017).

The present study aims to empirically extend our understanding of the link between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement based on students’ perceptions using uniform measures across six contrasting national contexts. In addition, it also aims to explore the role of certain personal variables in the interplay between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement cross-nationally. The study includes representatives of both Western and Eastern contexts.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Teaching Behaviour

This study applies a conceptualization of teaching behaviour that is grounded in the teaching and teacher effectiveness literature (e.g., Hattie, 2009; Muijs et al., 2014; Van de Grift, 2014). Teaching behaviour refers to teachers’ acts contributing to student learning and outcomes (Maulana et al., 2021). Some examples include showing respects in the learning process, providing students with clear examples, and requesting students to reflect on their learning approaches.

Typically, the variety in effective teaching behaviours is grouped into seven broader domains (Bell et al., 2019; Muijs et al., 2014). Past research in Indonesia, South Korea, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, and Turkey shows that the variety in student perceptions of effective teaching behaviors can be represented by a six-factor structure labelled as: safe and stimulating learning climate, efficient classroom management, clarity of instruction, activating teaching, teaching learning strategies, and differentiation (André et al., 2020; Inda-Caro et al., 2019; Maulana & Helms-Lorenz, 2016).

Scholars show that teaching behaviours, based on observation data in the Netherlands, can be ordered hierarchically along a latent continuum (Van de Grift et al., 2011). This complementary conceptualization of teaching behaviour is grounded in theories on teacher development proposed by Berliner (2004) and Fuller (1969). Other scholars show that the unidimensionality of teaching behaviour, based on student perceptions data in the Netherlands, is confirmed (Maulana et al., 2015a; Van der Lans & Maulana, 2018; Van der Lans et al., 2015). The current evidence-base has been extended to other cultural contexts including Indonesia, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, and Turkey (Maulana et al., 2015b; Van der Lans et al., 2021).

2.2 Student Engagement

Student engagement is multifaceted and multidimensional in nature (Alrashidi et al., 2016). It is frequently conceptualized as the extent to which students are behaviourally and psychologically engaged in academic tasks (Appleton et al., 2006; Van de Grift, 2007; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Behavioural engagement refers to participation and involvement in academic, social or extracurricular activities, shown in terms of attendance, time spent on assignments, concentration, and attention. The focus is on students’ actions and practices that are directed toward school and learning (e.g., The student tries to work hard in class, shows a positive conduct and effort, participates in class discussions, follows the rules, and pays attention). Behavioural engagement is important for achieving positive academic outcomes and for preventing school dropout.

Emotional engagement refers to the extent of positive and negative reactions to teachers, classmates, academics and school, shown in terms of interest and positive attitude. The emphasis is on students’ affective reactions and sense of identification with school (e.g., how students feel in the classroom, whether they enjoy learning new things, get involved when they are working on something or show interest (Fredricks et al., 2004; Jimerson et al., 2003; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Emotional engagement is linked to strengthening ties to school and willingness to perform academic work.

2.3 Perceived Teaching Behaviour and Engagement

Student engagement is a malleable variable that depends on environmental contexts (Marks, 2000; Pianta et al., 2012). Instead of solely associating it with a trait of an individual, the contemporary definition of engagement emphasizes the interaction between an individuals’ characteristics and their environments (Thijs & Verkuyten, 2009). Previous studies have shown that teaching behaviour contributes to a range of student outcomes (e.g., Pianta & Allen, 2008). Teachers’ provision of emotional support to students has been linked with various positive academic outcomes including social skills and academic competence (Malecki & Demaray, 2003), teacher reports of high levels of student participation in class, students’ self-reports of engagement and task completion (Anderson et al., 2004), subjective well-being (Suldo et al., 2009), school satisfaction (Richman et al., 1998), experience of meaningfulness of schoolwork and on-task orientation (Thuen & Bru, 2000).

Studies show that student perceptions of teaching behaviour has a powerful effect on students’ self-report of cognitive and behavioural engagement (Bertills et al., 2019; Davidson et al., 2010). Particularly, Inda-Caro et al. (2019) found that perceived emotional engagement was more strongly related to perceived teaching behaviour than perceived behavioural engagement. Furthermore, Klem and Connell (2004) found that perceived teaching behaviour was also related to classroom and school engagement (effort and attention in classes, being prepared for classes and finding school personally important). Ryan and Patrick (2001) found that perceived classroom emotional support was related positively to perceived engagement in self-regulated learning, and negatively to off-task and disruptive behaviour in the classroom. Den Brok et al. (2005) show that perceived teacher friendliness in the classroom is associated with perceived willingness to put effort into learning the school subject.

Taken together, there is evidence that student perceptions of effective teaching behaviour contribute positively to their perceptions of various academic outcomes. In classrooms with highly effective teachers, students’ needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy are met (Deci & Ryan, 2000), which is reflected in student behavioural and emotional engagement and successful learning (Virtanen et al., 2015). However, there is evidence that teaching behaviour in secondary schools varies between classrooms (Malmberg et al., 2010; Maulana et al., 2015b) and between countries (Maulana et al., 2021), suggesting that not all secondary school students perceive high-quality teaching and learning at all times. Therefore, this variation is to be expected at the classroom level across countries.

2.4 Perceptions of Teaching Behaviour and Student Engagement: Gender, Age, and School Subject

The present study focuses on secondary school students. These students are in the adolescent period, which is characterized by changes in biological, cognitive, emotional, and social reorganisation (Susman & Rogol, 2013). Hence, their personal characteristics may play a role in the interplay between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement. A limited number of studies investigate the link between certain personal characteristics with either engagement or teaching behaviour separately. To our knowledge, studies examining the mediating effect of students’ characteristics on the two key constructs are underrepresented in the literature. The current study aims to test the mediating effect of several personal background on the relationship between perceived teaching quality and engagement across countries. Thus, student gender, age, and school subject are focused on.

2.4.1 Student Gender and Engagement

In general, research has consistently shown that boys show lower academic engagement than girls. This trend is consistent across primary, secondary, and higher education. For example, Cooper (2014) found that in Grades 9–12, boys reported lower engagement than girls in the United States. A large-scale study involving 7th–9th graders in 12 countries (Austria, Canada, China, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Malta, Portugal, Romania, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States) show a similar trend (Lam et al., 2014). Jelas et al. (2014) and Amir et al. (2014) confirmed similar finding among 12–16 years old students in Malaysia. This trend was also visible among university students in Malaysia (Teoh et al., 2013). More recent studies involving primary school students in Japan (Oga-Baldwin & Fryer, 2020), primary and lower secondary school in Norway (Havik & Westergard, 2020), upper secondary school students in China (Teuber et al., 2021), and a wide range of age-groups (12–25 years old) in Portugal (Santos et al., 2021) show consistent findings.

In secondary education, academic engagement tends to decline for both boys and girls over time. This trend was found in Flanders (Dutch-speaking part of Belgium) (Lamote et al., 2013; Van de Gaer et al., 2009), The Netherlands (Opdenakker et al., 2012), and the United States (Wang & Eccles, 2012). A larger decline in engagement was found for boys than for girls in Canada (Chouinard & Roy, 2008), The United States (Dotterer et al., 2009), and Australia (Watt, 2000). A meta-analysis study shows that, under equal levels of intellectual ability, girls are more likely to be academically successful because they engage more in schoolwork than boys over time (Lei et al., 2018).

Existing studies on gender and engagement are typically fragmented including single contexts. An exception is the study of Lam et al. (2012) studying gender differences in engagement among 7th and 9th graders across 12 countries. Lam et al. found that girls reported higher levels of school engagement compared to boys. The teachers rated girls higher in academic performance compared to boys. However, student gender did not moderate the relation among student engagement, academic performance, or contextual supports (Lam et al., 2012).

2.4.2 Student Age and Engagement

Research has consistently shown that, in general, younger students tend to show higher engagement than older students. For example, younger students in primary schools reported higher emotional engagement than older students in lower secondary schools (Havik & Westergard, 2020). In a study involving students aged 12–16 years old in Malaysia, younger students reported higher engagement compared to older students (Amir et al., 2014). A similar trend was also found in Portugal involving samples of students aged 12–25 years old (Santos et al., 2021), in Canada involving secondary school students (grade 9–11) (Chouinard & Roy, 2008), and in The United States involving junior high and high school students (Dotterer et al., 2009). Students in senior grades are less likely to be interested in learning than students in junior grades (Lam et al., 2007). In a study involving 12 countries, Lam et al. (2016)) found a declining trend in perceived engagement among grade 7–9 students, suggesting that perceived engagement becomes lower as students get older.

There are studies regarding the link between student gender and age and academic engagement. In general, at all grade levels in primary and secondary schools, boys consistently reveal less academic engagement than girls (Finn, 1989; Finn & Cox, 1992; Lee & Smith, 1993). More recent studies confirmed that younger female students tend to report higher levels of engagement and satisfaction with school than older male students (Amir et al., 2014; Hartono et al., 2020; Inchley et al., 2020).

2.4.3 School Subject and Engagement

Research documenting differences in engagement across school subjects are scarce. Nevertheless, it is much discussed in school practice that engaging students academically is a challenge for many teachers, irrespective of the school subject they teach. Scholars acknowledge that “engaging students in science and helping them develop an understanding of its ideas has been a consistent challenge for both science teachers and science educators alike” (Hadzigeorgiou & Schulz, 2019, p. 1). Although engagement is not a school subject-specific problem, variations in engagement across school-subjects are expected due to different characteristics of the subject (e.g., difficulty level).

2.4.4 Student Gender and Teaching Behaviour

In general, there is evidence from Western contexts that boys tend to report lower levels of teacher support (Oelsner et al., 2011; Soenens et al., 2012; Vansteenkiste et al., 2012). Girls tend to rate their teachers more favourably than boys (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). Evidence from Flemish secondary schools show that boys reported lower teacher support than girls (Lietaert et al., 2015). Similarly, Maulana et al. (2014) found that girls reported higher level of teacher support in terms of influence than did boys in Indonesian secondary schools. However, another study from Indonesia shows that student gender has no significant link with perceived teaching behaviour in terms relatedness, structure, and autonomy support (Maulana et al., 2016).

2.4.5 Student Age and Teaching Behaviour

In general, the link between student age and perceived teaching behaviour is underrepresented in the literature. A study in Spain shows that students in lower secondary education rated their teachers more favourably than did their peers in upper secondary education (Fernández-García et al., 2019). A study in Indonesia shows that grade level, which corresponds to student age, has no significant link with their perceived teaching behaviour (Maulana et al., 2016).

2.4.6 School Subject and Teaching Behaviour

Given that curricular materials are largely content specific, and teacher guides for textbooks are differentially elaborated in different subjects (Remillard, 2005; Reutzel et al., 2014), differences in teaching behaviour across subjects are to be expected. The way a school subject is perceived can influence teaching (Grossman & Stodolsky, 1994). Nevertheless, the link between school subject and perceived teaching behaviour is inconclusive. In addition, there is little empirical evidence about the stability in an individual teacher’s practice across different subjects (Cohen et al., 2018), particularly in secondary education. A limited number of studies in primary schools generally show that teachers’ practices vary across subjects (Cohen et al., 2018; Graeber et al., 2012; Knapp et al., 1995). This suggests that the variation in the effectiveness of teaching behaviour across subjects may exist. For example, a study in the United States indicated a slightly higher quality of teaching behaviour for English teachers compared to mathematics teachers (Cohen et al., 2018). Another study examining whether students’ perceptions of their teachers’ interpersonal behaviour relates to students’ subject-related attitudes across different school subjects from grades 9 to 11 revealed that an interpersonal Affiliation style is beneficial for all students, irrespective of the subject matter (Telli, 2016). It is important to note that the studies mentioned above used other, mostly qualitative, methods (e.g., interviews, classroom observation, teacher logs).

In secondary education, Maulana et al. (2012) found that Indonesian English as Foreign Language (EFL) teachers were perceived friendlier compared to mathematics teachers. Similarly, students in Western contexts reported that psychosocial classroom climates of math and science classes were less favourable compared to other school subjects (Den Brok et al., 2010; Levy et al., 2003). However, another study in The Netherlands reports that science and math teachers were perceived as more dominant and friendly compared to their colleagues from other school subjects (Den Brok et al., 2004). Similarly, a study in Indonesia shows that math and science teachers were perceived more positively in the provision of relatedness, structure, and autonomy support than other school subjects (Maulana et al., 2016). In addition, other scholars did not find a significant effect of school subject on perceived teaching behaviour in Indonesia (Maulana et al., 2014) and in The Netherlands (Maulana et al., 2015b).

Taken together, there seems to be a tendency that boys and older students tend to report lower engagement and less positive perceived teaching behaviour compared to girls and younger students. However, the role of school subject in explaining differences in perceived engagement and perceived teaching behaviour is inconclusive. Furthermore, studies of the mediating effect of student gender, age, and subject school on the link between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement are scarce. One study in the Flemish secondary school context examined the mediating effect of teacher support on the link between student gender and engagement, showing that teacher’s provision of autonomy support and involvement partially mediated the relationship between gender and behavioural engagement (Lietaert et al., 2015). Although Lietaert et.al did not investigate the mediating role of student gender, their study suggests a potential interplay between gender, teaching behaviour, and engagement.

Based on the literature review, it is expected that student gender, student age, and school subject will play a role, at least to some degree and in certain educational contexts, in the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported student engagement.

3 Context of the Current Study

Henrich et al. (2010) express that most of the psychological knowledge is built on studies from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. Most cross-cultural or cross-national studies have not directly investigated the link between teaching behaviour and engagement, and the mediating role of certain background factors, across WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries. The current study aims to examine the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement, and the mediating/moderating effect of background variables (i.e., student gender, age, and school subject) on the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement across six contrasting countries: The Netherlands, Spain, Turkey, South Africa, South Korea, and Indonesia.

This study used part of the data collected in an international project on teaching quality initiated by University of Groningen, The Netherlands. The multinational project involved 16 countries. In this study, data from six countries are included from both WEIRD (i.e., The Netherlands, Spain) non-WEIRD (South Africa, Indonesia) and in between WEIRD and non-WEIRD (South Korea, Turkey) societies, with contrasting cultural values and socio-economic development background.

3.1 Cultural Dimension

The six countries share some similarities and differences in terms of cultural dimensions and educational performance. There are at least two cultural dimensions depicting the diversity and the similarity of the six countries that are relevant to this study: Power Distance index (PDI) and Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV)Footnote 1 (Hofstede et al., 2010). Of the six countries, the Netherlands has the lowest score (PDI = 38). The Dutch society is characterized by being independent, hierarchy for convenience only, and equal rights. Superiors facilitate, empower, and are accessible. Decentralization of power is applied in which superiors count on the experience of their team members. Employees expect to be consulted. Control is disliked, attitude towards superiors is informal, and communication is direct and participative. Spain (PDI = 57), South Korea (PDI = 60), Turkey (PDI = 66) and Indonesia (PDI = 78) respectively have higher power distance scores. In high power distance countries, people are dependent on hierarchy. Superiors are directive and controlling. Centralized power is applied in which obedience to superiors is expected. Communication is indirect and people tend to avoid negative feedback (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010).

Of the six countries, the Netherlands revealed the highest in IDV (80), meaning that the country is characterized by a highly individualist society. In this country, a loosely-knit social framework is highly preferred. Individuals are expected to focus on themselves and their immediate families. The superior and inferior relationship is based on mutual advantage, and meritocracy is applied as a base for hiring and promoting individuals. Management focuses on the management of individuals. The remaining countries are considered collectivistic, with Indonesia as the most collectivistic (14), followed by South Korea (18), Turkey (37), and SpainFootnote 2 (51) respectively. In the collectivistic society, a strongly defined social framework is highly preferred. Individuals should conform to the society’s ideals and the in-groups loyalty is expected. Superior/inferior relationships are perceived in moral terms like family relationships. Management focuses on management of groups. In some collectivistic countries like Indonesia, there is a strong emphasis on (extended) family relationships, in which younger individuals are expected to respect older people and taking care of parents is highly valued (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010).

With respect to educational performance, the latest worldwide study of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)Footnote 3 2018 showed that South Korea’s performance was well above the OECD average and listed among the top 5. The Netherlands’ average performance was also above the OECD average but below the South Korean performance. Spain was positioned slightly below the OECD average. Turkey’s mean performance in mathematics improved in 2018 while enrolling many more students in secondary education between 2003 and 2018 without sacrificing quality of the education. Indonesia was listed well-below the OECD average and the lowest compared to the other four countries (OECD, 2019).

4 Socio-economic Dimension

Socio-economic background is another prevalent factor in country development. Given the country’s socio-economic background, variations in the link between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement, coupled with students’ personal background, are expected. Thus, it is important to examine whether the direction and the magnitude of associations between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement are similar between developed (e.g., The Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Turkey) and developing contexts (South Africa, Indonesia) (United Nations Development Programme, 2022).Footnote 4 Past research shows that family involvement in education is more strongly related to science achievement in more developed countries (Chiu, 2007). It was also found that teacher-student relationship is more strongly associated with students’ perceived classroom discipline in more developed countries (Chiu & Xihua, 2008). Studies investigating the link between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement involving developed and non-developed contexts are underrepresented. One multinational study involving 12 developed and non-developed nations indicates that most of the associations between the contextual factors (e.g., instructional practices, teacher support) and student engagement did not vary across countries (Lam et al., 2016).

Based on the literature review, it expected that the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported student engagement across developed and non-developed settings included in this study will not vary significantly. Because it is unclear whether or not the link between perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported engagement depends on socio-economic dimension, no expectation regarding differences between developed and developing educational contexts can be made. Rather, this will be examined in an explorative manner.

5 Research Questions

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

How does the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement compare between countries?

-

2.

How does student gender, student age, and school subject mediate the relationship between student engagement and perceived teaching behaviour across countries?

6 Method

6.1 Sample

This study is part of a larger project on differentiation from an international perspective involving 16 countries, led by the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. For the present study, data from Indonesia, the Netherlands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, and Turkey are included. In total, 40,788 secondary school students filled in the questionnaire in the six countries. Data were collected during the years 2015 (Indonesia, South Korea and the Netherlands), 2016 (South Africa and Spain), and 2017 (Turkey) using a combination of online and paper and pencil methods depending on the resources in the participating countries. Teaching behaviour and student engagement questionnaires were administered during the same period. Only the first year of data collection was included in this study. Data included perceptions of teachers with subjects from natural sciences, social sciences and languages. In all countries, data were approximately uniformly distributed across different subjects, student age and student gender (Table 20.1). Students participated in the study on a voluntary basis.

For the present study, a selection of eligible, more balance, sample was done, including Indonesia (n = 6329 students; 299 teachers; 24 schools), the Netherlands (n = 6590; 300 teachers; 148 schools), South Africa (n = 4034; 270 teachers; 10 schools), South Korea (n = 6976; 336 teachers; 26 schools), Spain (n = 4524; 251 teachers; 48 schools), and Turkey (n = 7434; 274 teachers; 16 schools). The selection comprised a random subset of five students per class for the analysis. This selection balanced the considerable variation in class size found within and between countries (Min(class size) = 6; Max(class size) = 96). Especially, the exceptionally large class sizes of over 40 students were of concern, because they might have been two classes taught by the same teacher. The random selection attempted to control for this. The selection was completely random except for two criteria. A number of 355 students was not considered for selection because they had more than five missing values on the teaching behaviour or more than two missing values on engagement questionnaire. Another number of 653 students that could not be classified to one of the domains language, natural sciences or social sciences subjects.

6.2 Measures

Student perceptions of teaching behaviour was measured using My Teacher Questionnaire (Maulana et al., 2015a, b; Van der Lans et al., 2015) The questionnaire comprises 41 items that operationalize six domains of teaching behaviour: safe learning climate, clear and structured instruction, activating teaching, teaching learning strategies, differentiation. Response categories were provided on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Students’ responses were calibrated into a unidimensional and comparable metric using Partial Credit Model (PCM) with quasi-international concurrent linking method (Van der Lans et al., 2021). Hence, teaching behaviour was analyzed as the unidimensional construct. This unidimensional construct has been proven to be valid and reliable, as well as invariant, across the six countries (Van der Lans et al., 2021).

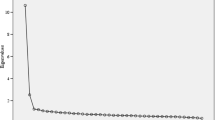

Perceived engagement was measured using the student engagement scale of Skinner et al. (2009). This scale measures emotional (5 items; e.g. “In this class I feel good”), and behavioural engagement (5 items; e.g. “In this class I pay attention“). Reliability of the measure is satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 and 0.83 for behavioural and emotional engagement respectively). All items are scored on a four-point scale, with higher responses indicating higher engagement levels. To examine the measurement invariance across the six countries, the engagement scale was subject to Multilevel Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MMGCFA) in which students were clustered within teachers, after the factor structure was confirmed in each country data (see Fig. 20.1). For this analysis, a random subset of five students was selected from every teacher. Results show that the scale reached the partial metric invarianceFootnote 5 (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.08) (Hoyle & Panter, 1995), allowing us to compare the correlation between countries.

Both questionnaires were translated and back-translated for use in the six countries using procedures in accordance with International Test Commission (2017).

6.3 Analysis Approach

To answer the first research question, “How does the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement compare between countries?”, as a first step, simple Pearson product correlations were estimated correlating the mean score with behavioral engagement and emotional engagement with the estimated perceived teaching behaviour. The concurrent quasi-international calibration approach was employed (see Van der Lans et al., 2021). Then, the correlations between the latent (estimated) student engagement and perceived teaching behaviour were computed, by applying a multi-level multi-group SEM model. Student perceived teaching behaviour was added as a predictor of the latent variables student behavioral and emotional engagement.

To answer the second research question, “How does student gender, student age, and school subject mediate the relationship between student engagement and perceived teaching behaviour across countries?” three multi-level multi-group SEM analyses were performed. Three models were examined testing the mediation effect of student gender, student age and school subject separately. Results focus on the variation in the predictive effect of perceived teaching behaviour on students’ behavioral and emotional engagement.

All analyses were performed in R (4.0.3) (R Core Team, 2021), and Rstudio (1.1.456) and SPSS 27. The R packages used were “lavaan” (version info; author) and “SEMtools” (version info; Jorgensen, 2021). All SEM models considered the items scores on the engagement as ordinal. Estimation was performed with the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator. Although teacher ID codes were available, lavaan does not allow multilevel estimation with ordered data. An empirical comparison using model fit coefficients favoured the specification of ordered item responses over the specification of interval level item responses. Models were grouped by country identification code (ID) using the group command. The three mediators were coded: Student gender (0 = male, 1 = female), Student age (1 = 11 years, until 10 = 20 years old), and teacher subject (1 = languages, 2 = natural sciences, 3 = social sciences,). The variable student age was considered of interval level. The variable teacher subject was dummy coded into three dummy variables, namely: subject1_dummy (0 = other subject, 1 = language), subject2_dummy (0 = other subject, 1 = natural sciences), and subject3_dummy (0 = other subject, 1 = social sciences).

7 Results

7.1 Relationship Between Perceived Teaching Behaviour and Student Engagement

Results show that, in general, there are differences in perceived teaching behaviour (TB) across the countries and the differences in the raw mean of student engagement scales are visible but smaller (see Table 20.2). Interestingly, South African students reported the highest raw mean of perceived behavioural engagement (BE) (M = 3.38, SD = 0.55) and second highest raw mean score of emotional engagement (EE) (M = 3.30, SD = 0.57), but the country had the second lowest (latent) mean perceived teaching behaviour (TB) score (M = 1.90, SD = 1.50).

In all countries, the Pearson correlations are positive, with moderate to strong in magnitude (r = 0.32 in Spain – 0.70 in The Netherlands). In general, the correlations are slightly stronger for emotional engagement compared to behavioural engagement. Using the latent score of engagement scales instead of the raw scores produced generally stronger correlations with latent perceived teaching behaviour in all countries (see Table 20.1). The magnitude of the correlations varies from highly moderate (r = 0.40 in Spain) to strong (r = 0.80 in The Netherlands). In general, results show that perceived teaching behaviour are related positively, and mostly strongly, to student engagement across the six countries. This means the higher the perceived teaching behaviour, the higher students reported their academic engagement, and vice versa. Slight differences in the magnitude of relationships between perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported engagement are evident. The strongest link was found in the Netherlands (0.80), followed by South Korea (0.73), South Africa, Indonesia, Turkey, and Spain.

7.2 Student Gender, Student Age, School Subject, Teaching Behaviour and Engagement

In the subsequent step, mediation effects were added for student gender, age and school subject separately. As a first step, the model without mediator is estimated. This model adds the regressive effect of emotional engagement and behavioural engagement separately on teaching behaviour. These direct effects are significant in all countries, except in Spain (β = −0.07, p = 0.45). In the second step, the mediation variables were added.

Regarding student gender (see Table 20.3), results reveal no mediation effects. In all countries, student gender has non-significant effect on perceived teaching behaviour. Only in Turkey and the Netherlands emotional and behavioural engagement have a significant effect on student gender, meaning that the level of engagement is related to student gender within these countries. Effects are positive for perceived behavioural (βNLD = 0.10; βTR = 0.25) and negative for perceived emotional engagement (βNLD = −0.17; βTR = −0.24).

Regarding student age (see Table 20.4), results indicate partial mediation for emotional engagement in Turkey. The direct effect of perceived emotional engagement on perceived teaching behaviour remains dominant (βTR = 0.36), but in addition a small significant and positive indirect effect is found (βTR = 0.02). The indirect effect suggests that relatively higher levels of perceived emotional engagement are found with relatively older students and this in turn affects the level of perceived teaching behaviour. This mediation is unique to Turkey, however, and not replicated in the other countries.

In South Korea, South Africa, Spain and Turkey, a significant direct effect of student age on perceived teaching behaviour is found. The direction, however, differs between the four countries. In Spain (βESP = −0.07) and South Africa (βZAF = −0.06), a small negative direct effect is found which indicates that older students perceived somewhat lower levels of teaching behaviour. In Turkey (βTR = 0.11) and South Korea (βKOR = 0.05), a small positive direct effect is found which indicates that older students perceive somewhat higher levels of effective teaching behaviour. In the Netherlands and Indonesia, the effect of student age on teaching behaviour is non-significant. In the Netherlands, student behavioural (βNLD = −0.24) and emotional engagement (βNLD = −0.14) reveal a significant and negative effect on student age suggesting that student age is associated with the level of perceived engagement. This finding is unique to the Netherlands and not replicated in the other countries.

Regarding school subject (see Tables 20.5, 20.6, and 20.7), the results provide no evidence for mediation effects. In South Korea, the Netherlands, South Africa and Turkey the language subject domain has small effect on the level of perceived teaching behaviour. Only in South Korea (βKOR = −0.04), the direction of the effect is negative meaning that South Korean students experienced a somewhat lower level of effective teaching behaviour in language classes. In the Netherlands (βNLD = 0.06), South Africa (βZAF = 0.08) and Turkey (βTR = 0.05), the students experienced a somewhat higher level of teaching in language classes. In Indonesia and Spain, no significant effects were found related to language subjects.

With respect to the domain natural sciences (see Table 20.6), the reverse pattern is observed. In South Korea, the Netherlands, South Africa and Turkey the natural science domain has small effect on the level of teaching behaviour. Only in South Korea (βKOR = 0.05) the direction is positive meaning that South Korean students perceive slightly higher levels of effective teaching behaviour in natural science classes. In the Netherlands (βNLD = −0.04), South Africa (βZAF = −0.09) and Turkey (βTR = −0.06), the students experienced a somewhat lower level of effective teaching behaviour in language classes. In Indonesia the level of emotional engagement (βIDN = 0.22) is related to a natural science subject domain, while in Spain the level of emotional (βESP = 0.29) and behavioural engagement (βESP = −0.31) significantly predicts the natural science subject domain. Within these two countries, higher levels of emotional engagement are associated with natural science classes and Spanish students report lower levels of behavioural engagement in natural science classes.

With regard to the social science subject domain (see Table 20.7), only one significant effect is found. This effect is present in the Netherlands, indicating that higher levels of emotional engagement are evident in social science subject classes (βNLD = 0.14).

8 Conclusions and Discussion

The present study aims to explore the links between perceived teaching behaviour and student engagement across six diverse national contexts. It also aims to explore the role of student gender, age, and school subject in the interplay between perceived teaching behaviour and engagement cross-nationally.

8.1 Perceived Teaching Behaviour and Student Engagement Across Countries

We found that perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported student engagement are significantly and positively related, and this finding is consistent across the six countries. Our finding suggests that perceived teaching behaviour is important for student engagement cross-nationally, and vice versa. This finding is in line with other studies showing that student perceptions of teaching behaviour have a powerful effect on students’ self-report of cognitive and behavioural engagement (Bertills et al., 2019; Davidson et al., 2010).

In general, the link between perceived teaching behaviour and emotional engagement is stronger compared to behavioural engagement, and this trend is consistent across the six countries. This finding is consistent with past research in Spain (Inda-Caro et al., 2019). Self-Determination (SDT) stresses the importance of students’ emotional engagement in facilitating internalization of goals, values, and important skills in schools (Ryan & Deci, 2009; Skinner & Pitzer, 2012). Students’ perceived relatedness with teachers facilitates the internationalization of values and goals promoted by schools, which leads to the adoption of practices related to behavioural engagement (Ryan & Deci, 2009).

However, differences in the magnitude of correlations are visible, suggesting differential importance of perceived teaching behaviour for student engagement cross-nationally. Based on the latent score correlation, the relationship between perceived teaching behaviour and behavioural engagement is strong in Indonesia, South Korea, The Netherlands, and South Africa, and highly moderate in Spain and Turkey. For emotional engagement, strong relationships with perceived teaching behaviour are evident in all countries. Note, however, that the correlation coefficient for Spain is only very close to strong (r = 0.49). The relationships between perceived teaching behaviour and both types of engagement are strongest in The Netherland, and weakest in Spain.

The Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, and Turkey can be categorized as developed contexts, while Indonesia and South Africa as developing contexts (UNDP, 2022). The fact that the weakest correlations between perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported engagement was found in Turkey and Spain suggests that the socio-economic dimension divide (e.g., developed vs. developing) plays a marginal role in explaining the link between the two psychological constructs. These differences may be more related to cultural factors of the six countries (Hofstede et al., 2010). Quantitatively (not in terms of Cohen’s criteria), the link between the psychological constructs is strongest in the Netherlands, especially when it comes to perceived teaching behaviour and self-reported emotional engagement. The Netherlands has the lowest power distance index and the highest individualistic index, compared to the remaining five countries (Hofstede et al., 2010). In general, there seems to be modest between-country variation in the strength of the association. The implications of this variation need yet to be explored.

To conclude, regardless of the cultural background and the degree of country development, perceived teaching behaviour is significantly, and generally strongly, related to student engagement. The findings underscore the assumed universal importance of perceived teaching behaviour for student engagement, regardless of the cultural dimensions and the availability of the country’s physical resources.

8.2 Student Gender, Age, School Subject, Teaching Behaviour and Student Engagement Across Countries

In general, the results show mixed evidence and generally do not support the presence of mediation effects. Only one mediation effect was found. Moreover, other single direct effects between perceived teaching behaviour and the mediators and between the mediators and perceived engagement were not fully consistent across countries in terms of directions and sizes. Adding the mediation variables did not substantially change the estimated direct effects of student perceived teaching behaviour on engagement. The evidence supports a view that student perceived engagement is primarily affected by student perceived teachers’ teaching effectiveness and is to only a modest extend explained by student gender, age and/or school subject.

Of the tested mediator variables, student age is the only mediator variable that shows a significant association in Turkey. Mediators only have marginal effects on the link between perceived engagement and perceived teaching behaviour.

8.3 Implications

The present study contributes to the advancement of scientific knowledge by revealing the universality and some specificity of the interplay between perceived teaching behaviour, perceived engagement, and some background variables across several diverse countries. The results should be able to fill the lacuna of the scientific research in the field, at least to some extent, in WEIRD, non-WEIRD, and in between WEIRD and non-WEIRD settings with diverse cultural backgrounds, and reveal how factors in the microsystem (i.e., teaching behaviour, personal and contextual characteristics) interact in the development of student engagement in school.

The study also contributes to the measurement field to some extent. Using the latent score of engagement scales, instead of the raw scores, produced stronger correlations with latent perceived teaching behaviour in all countries. Observed variables are contaminated with measurement errors, while latent variables are stripped from measurement errors (Cole & Preacher, 2014). Ignoring measurement errors will result in an estimate of a correlation/regression coefficient that is lower than the true value (Fleiss & Shrout, 1977). Hence, correlation coefficients using latent variables are more accurate. This finding is proven to be consistent across the six countries.

The study also has implications for educational practices. The findings of the universal importance of perceived teaching behaviour for perceived student engagement are encouraging to teachers and educators. Despite the cultural background and socio-economic development, teachers’ behaviour in the classroom and how it is perceived by their students is universally important for their academic participation in school. Efforts to support teachers to improve the effectiveness of their teaching behaviour seem globally relevant given the six diverse settings in our sample. Despite the assumed universal importance, perceived teaching behaviour is linked to engagement more strongly in some countries than in other countries. This implies that the powerful impact of perceived teaching behaviour varies to some extent across different national contexts. Some countries like The Netherlands and South Korea should keep investing in the teaching quality improvement, while in other countries like Indonesia, Spain, and Turkey, investing in teaching quality improvement may need to be done in concert with other meso- and macro-level educational factors to bring students’ engagement level to a higher level.

8.4 Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, the current study is subject to several limitations. First, convenience sampling was applied so generalizations of findings to country level should be handled with care until future replication studies with more representative samples are available. Furthermore, the sample and student characteristics across the five countries are not entirely similar. For example, a high proportion of inexperienced teachers dominated Dutch samples, so that perceived teaching behaviour largely applies to this teacher group. Students may perceive their teachers differently as a function of teaching experience. In the other four countries, on the contrary, higher proportions of experienced teachers were more visible. These sample characteristics may influence the results and, thus, the current results should be interpreted with caution until further replication studies with more representative samples are available.

Using self-reported engagement measure instead of actual engagement measure can also be viewed as a limitation. However, the focus of this study is on student perceptions, so the self-report measure (e.g., questionnaire) is deemed appropriate. Future research can benefit more from linking perceived teaching behaviour to actual engagement. The current study revealed the assumed universality as well as some specificity of the link between perceived teaching behaviour and perceived engagement. The findings showed that the associations between perceived teaching behaviour are significant, albeit different in magnitude. As also echoed by Lam et al. (2016), these findings underline the significance of integrating the etic and emic approaches in future cross-country studies and promote the search for the ‘middle ground’ acknowledging both cross-cultural similarities and differences (King & McInerney, 2014).

Notes

- 1.

The country data for South Africa related to these cultural values is not available. The current available data of South Africa is limited to the White population only, which is a minority group in the country.

- 2.

Spain is seen as collectivist in comparison to the rest of European societies (except Portugal), but for the rest of the world it is individualist as noted in the reference.

- 3.

South Africa did not participate in the PISA study. Hence, the performance data for South Africa is not available.

- 4.

Based on Human Development Index (HDI) developed by the United Nations. HDI score of ≥ 0.80 = developed, and < 0.80 = developing. Based on the 2020 report, the HDI of the six countries is as follows respectively: The Netherlands = 0.94; South Korea = 0.92; Spain = 0.90; Turkey = 0.82; Indonesia = 0.72; South Africa = 0.71). See: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506

- 5.

The parameters freed were: South Africa = residual correlation item 4 and 5 was, The Netherlands = residual correlation item, Indonesia, South Korea and Spain = residual correlation item 3 and 10, item 6 and 8, Indonesia = residual correlation item 3 and 5, South Korea, the Netherlands and South Africa = the scaling factor of item 3. Overall, item 3 was the most problematic. Interpretation of partial invariance suggests that not all parameters have identical interpretation across countries. In this study, only a small number of items does not meet strict invariant. By freeing the residual correlations (and one scaling factor), we were able to fix all 10 factor loadings to be identical across countries. Since factor loadings determine the factor’s metric, comparing the factor scores and associations between countries with relatively small number of freed residual inter-item correlations is deemed acceptable. Item deletion was not preferred because all items were assumed to measure aspects of perceived teaching behaviour uniquely based on face validity, and minor violations in the model are allowed because the model is not perfect but is still within the acceptable boundary given the complexity of the model and the large number of variables and parameters involved.

- 6.

An earlier version of this chapter was presented at the 33rd International Congress for School Effectiveness and Improvement, January 2020, Marrakesh, Morocco.

References

An earlier version of this chapter was presented at the 33rd International Congress for School Effectiveness and Improvement, January 2020, Marrakesh, Morocco.

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., & Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: An overview of its definitions, dimensions, and Major conceptualisations. International Education Studies, 9(12), 41–52.

Amir, R., Saleha, A., Jelas, Z. M., Amad, R., & Hutkemri. (2014). Students’ engagement by age and gender: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 21(10), 1886–1892. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2014.21.10.85168

Anderson, A. R., Christenson, S. L., Sinclair, M. F., & Lehr, C. A. (2004). Check and connect: The importance of relationships for promoting engagement with school. Journal of School Psychology, 42, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2004.01.002

André, S., Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Telli, S., Chun, S., Fernández-García, C. M., et al. (2020). Student perceptions in measuring teaching behavior across six countries: A multi-group confirmatory factor analysis approach to measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 273.

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 427–445.

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369–386.

Bell, C. A., Dobbelaer, M. J., Klette, K., & Visscher, A. (2019). Qualities of classroom observation systems. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539014

Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265535

Bertills, K., Granlund, M., & Augustine, L. (2019). Inclusive teaching skills and student engagement in physical education. Front. Educ., 4, 74. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00074

Chiu, M. M. (2007). Families, economies, cultures, and science achievement in 41 countries: Country-, school-, and student-level analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.510

Chiu, M. M., & Xihua, Z. (2008). Family and motivation effects on mathematics achievement: Analyses of students in 41 countries. Learning and Instruction, 18, 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.06.003

Chouinard, R., & Roy, N. (2008). Changes in high-school students’ competence beliefs, utility value and achievement goals in mathematics. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709907X197993

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., Appleton, J. J., Berman, S., Spangers, D., & Varro, P. (2008). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 1099–1120). National Association of School Psychologists.

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. E. (2014). What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research (Project Report). Sutton Trust.

Cohen, J., Ruzek, E., & Sandilos, L. (2018). Does teaching quality cross subjects? Exploring consistency in elementary teacher practice across subjects. AERA Open, 4(3), 2332858418794492.

Cole, D. A., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Manifest variable path analysis: Potentially serious and misleading consequences due to uncorrected measurement error. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033805

Cooper, K. S. (2014). Eliciting engagement in the high school classroom A mixed-methods examination of teaching practices. American Educational Research Journal, 51(2), 363–402. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213507973

Davidson, A. J., Gest, S. D., & Welsh, J. A. (2010). Relatedness with teachers and peers during early adolescence: An integrated variable-oriented and person-oriented approach. Journal of School Psychology, 48(6), 483–510.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Den Brok, P., Brekelmans, M., & Wubbels, T. (2004). Interpersonal teacher behavior and student outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 15, 407–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0924345051233138262

Den Brok, P. J., Wubbels, T., Veldman, I. M. J., & van Tartwijk, J. W. F. (2005). Teachers’ self-reported and observed interpersonal behaviour in multicultural classrooms. In Integrating multiple perspectives on effective learning environments (pp. 1176–1177). University of Cyprus.

Den Brok, P. D., Taconis, R., & Fisher, D. (2010). How well do science teacher do. Differences in teacher-student interpersonal behavior between science teachers and teachers of other (school) subjects. The Open Education Journal, 3, 44–53.

Dotterer, A., McHale, S., & Crouter, A. (2009). The development and correlates of academic interests from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013987

Fernández-García, C. M., Maulana, R., Inda-Caro, M., Helms-Lorenz, M., & García-Pérez, O. (2019). Student perceptions of secondary education teaching effectiveness: General profile, the role of personal factors, and educational level. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00533

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117–142.

Finn, J. D. (2006). The adult lives of at-risk students: The roles of attainment and engagement in high school (NCES 2006–328). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Finn, J. D., & Cox, D. (1992). Participation and withdrawal among fourth-grade pupils. American Educational Research Journal, 29, 141–162.

Fleiss, L., & Shrout, P. E. (1977). The effects of measurement errors on some multivariate procedures. American Journal of Public Health, 67(12), 1188–1191. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.67.12.1188

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns of teachers: A developmental conceptualization. American Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 207–226.

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148.

Graeber, A., Newton, K., & Chambliss, M. (2012). Crossing the Borders again: Challenges in comparing quality instruction in mathematics and Reading. Teachers College Record, 114, 30.

Grossman, P., & Stodolsky, S. (1994). Content as context: The role of school subjects in secondary school teaching. Educational Researcher, 24(8), 5–23.

Guo, Y., Connor, C. M., Tompkins, V., & Morrison, F. J. (2011). Classroom quality and student engagement: Contributions to third-grade reading skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, Article 157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00157

Hadzigeorgiou, Y., & Schulz, R. M. (2019). Engaging students in science: The potential role of “narrative thinking” and “romantic understanding”. Frontiers in Education, 4, 38. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00038

Hartono, F. P., Sumarno, N. U., & Puji, R. P. N. (2020). The level of student engagement based on gender and amd grade on history subject of senior high school students in Jember regency. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 8, 21–26.

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Havik, T., & Westergard, E. (2020). Do teachers matter? Students’ perceptions of classroom interactions and student engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64, 488–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1577754

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

Hidayati, S. N., & Rodliyah, R. J. (2020). Eksplorasi Strategi Guru untuk Meningkatkan Keterlibatan Siswa dalam Aktifitas Membaca [Exploring Teacher’s strategies to encourage student engagement in reading activity]. Journal Penelitian Pendidikan, 20(1), 121–128.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the Mind (Rev. 3 rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 158–176). Sage.

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Budisavljevic, S., Torsheim, T., Jastad, A., Cosma, A., et al. (2020). Spotlight on adolescence health and wellbeing. Findings from the 2017/2018 health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada (International Report. Volume 1. Key findings). World Health Organization.

Inda-Caro, M., Maulana, R., Fernández-García, C. M., Peña-Calvo, J. V., Rodríguez-Menéndez, M., & Helms-Lorenz, M. (2019). Validating a model of effective teaching behaviour and student engagement: Perspectives from Spanish students. Learning Environments Research, 22(2), 229–251.

International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests (2nd ed.). www.InTestCom.org

Jelas, Z. M., Salleh, A., Mahmud, I., Azman, N., Hamzah, H., Hamid, Z. A., Jani, R., et al. (2014). Gender disparity in school participation and achievement: The case in Malaysia. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 140, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.387

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., & Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8(1), 7–27.

Jorgensen, T. D. (2021). Package ‘semTools’. https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/semTools/semTools.pdf

King, R. B., & McInerney, D. M. (2014). Culture’s consequences on student motivation: Capturing cross-cultural universality and variability through personal investment theory. Educational Psychologist, 49, 175–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.926813

Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 262–273.

Knapp, M. S., Shields, P. M., & Turnbull, B. J. (1995). Academic challenge in high-poverty classrooms. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(10), 770–776.

Lam, S.-F., Pak, T. S., & Ma, W. Y. K. (2007). Motivating instructional contexts inventory. In P. R. Zelick (Ed.), Issues in the psychology of motivation (pp. 119–136). Nova Science.

Lam, S.-F., Jimerson, S., Kikas, E., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Nelson, B., et al. (2012). Do girls and boys perceive themselves as equally engaged in school? The results of an international study from 12 countries. Journal of School Psychology, 50(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.004

Lam, S. F., Jimerson, S., Wong, B. P., Kikas, E., Shin, H., Veiga, F. H., et al. (2014). Understanding and measuring student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(2), 213.

Lam, S.-F., Jimerson, S., Shin, H., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Kikas, E., Wong, B. P. H., Stanculescu, E., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Liu, Y., Negovan, V., Nelson, B., Yang, H., & Zollneritsch, J. (2016). Cultural universality and specificity of student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12079

Lamote, C., Speybroeck, S., Van den Noortgate, W., & Van Damme, J. (2013). Different pathways towards dropout: The role of engagement in early school leaving. Oxford Review of Education, 39(6), 739–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.854202

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. B. (1993). Effects of school restructuring on the achievement and engagement of middle-grade students. Sociology of Education, 66, 164–187.

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality, 46, 517–528. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.7054

Levy, J., den Brok, P., Wubbels, T., & Brekelmans, M. (2003). Students’ perceptions of the interpersonal aspect of the learning environment. Learning Environments Research, 6(1), 5–36.

Lietaert, S., Roorda, D., Laevers, F., Verschueren, K., & De Fraine, B. (2015). The gender gap in student engagement: The role of teachers’ autonomy support, structure and involvement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12095

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

Malmberg, L., Hagger, H., Burn, K., Mutton, T., & Colls, H. (2010). Observed classroom quality during teacher education and two years of professional practice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 916–932.

Marks, H. M. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 153–184.

Maulana, R., & Helms-Lorenz, M. (2016). Observations and student perceptions of pre-service teachers’ teaching behavior quality: Construct representation and predictive quality. Learning Environments Research, 19, 335–357.

Maulana, R., Opdenakker, M.-C., Den Brok, P., & Bosker, R. J. (2012). In T. Wubbels, P. van den Brok, J. van Tartwijk, & J. Levy (Eds.), Interpersonal relationships in education: An overview of contemporary research (pp. 207–224). Sense Publishers.

Maulana, R., Opdenakker, M., & Bosker, R. (2014). Teacher-student interpersonal relationships do change and affect academic motivation: A multilevel growth curve modelling. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 459–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12031

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van de Grift, W. (2015a). Development and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring pre-service teachers’ teaching behaviour: A Rasch modelling approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(2), 169–194.

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van de Grift, W. (2015b). A longitudinal study of induction on the acceleration of growth in teaching quality of beginning teachers through the eyes of their students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.003

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Irnidayanti, Y., & Van de Grift, W. (2016). Autonomous motivation in the Indonesian classroom: Relationship with teacher support through the lens of self-determination theory. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(3), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0282-5

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van de Grift, W. (2017). Validating a model of effective teaching behaviour of pre-service teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(4), 471–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211102

Maulana, R., André, S., Helms-Lorenz, M., Ko, J., Chun, S., Shahzad, A., Irnidayanti, Y., Lee, O., de Jager, T., Coetzee, T., & Fadhilah, N. (2021). Observed teaching behaviour in secondary education across six countries: Measurement invariance and indication of cross-national variations, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(1), 64–95, https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1777170

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., Van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art–teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256.

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results: Combined Executive Summaries Volume I, II, II. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Combined_Executive_Summaries_PISA_2018.pdf (09.02.2022).

Oelsner, J., Lippold, M. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2011). Factors influencing the development of school bonding among middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(3), 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431610366244

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., & Fryer, L. (2020). Girls show better quality motivation to learn languages than boys: Latent profiles and their gender differences. Heliyon, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04054

Opdenakker, M.-C., Maulana, R., & Den Brok, P. (2012). Teacher-student interpersonal relationships and academic motivation within one school year: Developmental changes and linkage. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(1), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2011.619198

Pianta, R. C., & Allen, J. P. (2008). Building capacity for positive youth development in secondary school classrooms: Changing teachers’ interactions with students. In M. Shinn & H. Yoshikawa (Eds.), Toward positive youth development: Transforming schools and community programs (pp. 21–39). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327892.003.0002

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Allen, J. P. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In S. L. Christenson et al. (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (p. 365). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_17

Quin, D., Hemphill, S. A., & Heerde, J. A. (2017). Associations between teaching quality and secondary students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement in school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 807–829.

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Remillard, J. T. (2005). Examining key concepts in research on teachers’ use of mathematics curricula. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 211–246.

Reutzel, D. R., Child, A., Jones, C. D., & Clark, S. K. (2014). Explicit instruction in core reading programs. The Elementary School Journal, 114(3), 406–428.

Richman, J. M., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Bowen, G. L. (1998). Social support for adolescents at risk of school failure. Social Work, 43(4), 309–323.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Baroody, A. E., Larsen, R. A. A., Curby, T. W., & Abry, T. (2015). To what extent do teacher–student interaction quality and student gender contribute to fifth graders’ engagement in mathematics learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037252

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81, 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). Promoting self-determined school engagement. In K. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 171–195). Routledge.

Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437–460.

Santos, A. C., Simoes, C., Cefai, C., Freitas, E., & Arriaga, P. (2021). Emotion regulation and student engagement: Age and gender differences during adolescence. International Journal of Educational Research, 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101830

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer.

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kinderman, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028089

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioural and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Dochy, F., & Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025742

Suldo, S. M., Friedrich, A. A., White, T., Farmer, J., Minch, D., & Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38(1), 67–85.

Susman, E., & Rogol, A. (2013). Puberty and psychological development. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch2

Telli, S. (2016). Students’ perceptions of teachers’ interpersonal behaviour across four different school subjects: Control is good but affiliation is better. Teachers and Teaching, 22(6), 729–744.

Teoh, H. C., Abdullah, M. C., Roslan, S., & Daud, S. (2013). An investigation of student engagement in a Malaysian Public University. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 90, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.075

Teuber, Z., Tang, X., Salmela-Aro, K., & Wild, E. (2021). Assessing engagement in Chinese upper secondary school students using the Chinese version of the schoolwork engagement inventory: Energy, dedication, and absorption (CEDA). Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.638189

Thijs, J., & Verkuyten, M. (2009). Students’ anticipated situational engagement: The roles of teacher behavior, personal engagement, and gender. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 170(3), 268–286.

Thuen, E., & Bru, E. (2000). Learning environment, meaningfulness of schoolwork and on-task-orientation among Norwegian 9th grade students. School Psychology International, 21(4), 393–413.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Human development reports: Human development index (HDI). Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506

Van de Gaer, E., De Fraine, B., Pustjens, H., Van Damme, J., De Munter, A., & Onghena, P. (2009). School effects on the development of motivation toward learning tasks and the development of academic self-concept in secondary education: A multivariate latent growth curve approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 20(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450902883920

Van de Grift, W. (2007). Quality of teaching in four European countries: A review of the literature and application of an assessment instrument. Educational Research, 49(2), 127–152.

Van de Grift, W. J. (2014). Measuring teaching quality in several European countries. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(3), 295–311.

Van de Grift, W. J. C. M., Van der Wal, M., & Torenbeek, M. (2011). Ontwikkeling in de pedagogisch didactische vaardigheid van leraren in het basisonderwijs. Pedagogische Studiën, 88(6), 416–432.

Van der Lans, R. M., & Maulana, R. (2018). The use of secondary school student ratings of their teacher’s skillfulness for low-stake assessment and high-stake evaluation. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 58, 112–121.