Abstract

Every day more midwives and other healthcare practitioners (HCPs) realise that good care has to consider their clients’ sexual well-being. Still, many find it challenging to breach the topic during a consultation by talking to their clients about sexuality. This chapter explores the thresholds midwives and other healthcare practitioners experience when it comes down to talking about sex with their clients. Drawing on existing models of health and well-being, such as the biopsychosocial model of health, and existing models for communication in clinical settings, such as the ICE model, the chapter offers a simple and easy to use four-step communication model—starting with raising the issue of sexuality pro-actively and ending by making the client an offer. This approach can help healthcare practitioners to integrate sexuality into their daily practice.

“Talking sexuality” is a part of the more extensive publication “Sexuality & Midwifery”, an open access textbook published by Springer Nature, geared at midwives and related healthcare professionals, providing an overview of the current scientific knowledge on sexuality and midwifery, presented in a practice-oriented way.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This chapter offers a concrete, easy-to-use method to introduce the topic of sexuality in your midwifery practice. Based on four easy steps, the midwife, as a healthcare professional (HCP), can start a conversation about sexuality, listen to their client’s story, respectfully round up the conversation, and offer possible ways to meet the client’s needs. These steps will build on skills you already possess as a midwife. This method is a tool for discussing sexuality, even when you do not yet have experience addressing this topic with your client. Most HCPs will wonder and have questions like: “Can I bring up sex as a topic of interest? Won’t this be too intrusive? What will this woman think of me? How do I introduce sex as a topic? Do I have enough time to address the sexual concerns my client would voice? What if my clients ask me questions on sexuality that I don’t (yet) know how to answer?”

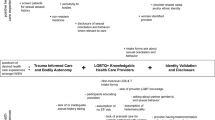

The One-To-One (“1T1”) model is based on different (counselling) models; the PLISSIT model [1], Motivational Interviewing [2], ICE client history taking [3], and the biopsychosocial model [4]. The final “1 T1” model (Fig. 26.1) was developed by SENSOA Footnote 1 in collaboration with various universities and professional organisations [5]. This chapter provides a concrete overview of the multiple steps to discuss sexuality with clients proactively. At each stage of the model, it will offer practical advice on how to implement this model in the daily midwifery practice directly.

2 Step 1 A: Pro-Actively Put Sex on the Table

This first step offers the HCP a handhold to start a conversation on sexual health topics. Often HCPs hesitate or doubt about proactively discussing sexuality with their clients: “Is this okay? I don’t want to approach this too directly. What will she think of me? Which questions are okay to ask and which are inappropriate? How do I do this in a helping and professional manner?”

-

This step entails nothing more than proactively starting a conversation about sexual health. Women don’t often bring up the topic of sexuality themselves. Reasons for this are numerous: feelings of shame and guilt, not knowing if sharing such concerns with the midwife is in line with the midwifery practice, etc. When sexuality is never proactively addressed, sexuality-related worries and troubles will stay hidden, and in addition, we implicitly give the message that sexuality should not be addressed.

-

The midwife knows that discussing sexuality can be vital to women’s health and well-being. Still, this link is not always clear for all women. That could cause women to be startled or caught unaware by the midwife raising the topic of sexuality. Two rules can ease this: explain why you want to talk about sex and ask permission.

The One-To-One (“1T1”) model: Proactively discussing sexual health with clients [5]

Out of the blue, “How is your sex life at the moment?” can be a rather intrusive question. Not understanding where that is coming from can raise questions in the woman or couple: “Why is the midwife asking me about sex? Is there something wrong with me? How am I seen? Why does the midwife want to know these things?”

While some assertive women might ask these questions, others might feel awkward being put in this position by their midwife and not venting their reactions. One can prevent such reactions by explicitly explaining why one wants to talk about sexuality and linking the question to general health.

Step 1 aims to introduce sexuality as a regular topic of conversation within midwifery practice in a non-intrusive way. It is recommended not to ask direct questions when introducing the theme of sexuality. Getting into details comes in step 2. When you refer to your midwife’s role and explain that looking after people’s sexual health is a standard part of midwifery practice, women and couples can handle the theme easier.

Example

Our job as a midwife is to monitor your general health and well-being, including sexual health. Would it be okay for you to talk about that?

You can also refer to standard practice or protocol in a midwifery or hospital team. That also depersonalises bringing up sexuality by linking it to one’s profession.

Example

“In our team, it is a protocol to talk to all women and couples about sexuality. We know that people don’t always bring up questions and concerns about sexuality themselves. Still, we feel it’s important to be able to help in this regard when necessary. Would it be okay if we make some time for that now?”

By explaining that the theme of sexual health is linked directly to your role and function as a midwife, asking about sexuality becomes less personal. This way, you can talk about sexual health positively and more neutrally.

In reality, the midwife will also bring up sexuality when expecting sexual problems. This suspicion can originate from professional instincts but more often because the midwife knows how physical or mental conditions or life events can impact women’s sexual well-being. An active childwish, pregnancy, and the postpartum period inevitably will change sexual practice and well-being. So midwives have an objective reason to proactively bring up the topic of sexuality and should always do so. Additional reasons to talk about sexuality with a specific client are, for instance:

-

Something you noticed during a physical exam: e.g. muscle tension.

-

Something you hear in her story: e.g. experience with sexual abuse.

-

Something you read in her file: e.g. history of depression.

The concerns that catch the midwife’s attention are often part of the woman’s situation or story. Still it remains advisable to introduce sexual health in a depersonalising manner. Like the theme is depersonalised by referring to team protocols or sexual health being “part of the midwife’s job” in the examples above, you can depersonalise individual concerns about this specific woman by referring to your professional knowledge or experience.

Referring to knowledge means that the midwife states that the concerns she noticed are known possible risk factors negatively impacting sexual health. For instance, saying as a fact: “We know that …”. You can also refer to research or professional guidelines. By stating the link between one’s concerns and sexual health as a known fact, the midwife again avoids appearing to speak specifically about her current client but rather about women in such positions in general.

Example

Research has shown that hormonal changes during pregnancy impact women’s levels of sexual desire and sexual arousability. “They tend to decrease at the beginning of pregnancy, then sometimes increase and again decrease towards the end.”

Other ways to factually introduce the theme of sexuality are: “Fertility problems often confuse a couple’s sexual relationship…;” “Young mothers often struggle with sexuality…”; “A pregnancy often induces fear of intercourse in couples…”.

The midwife can also depersonalise the topic by referring to her professional experience. By connecting the concerns noticed in this woman with earlier experienced similar situations, you address sexuality less directly. Referring to expertise can always be used, especially when we can’t yet refer to research data or protocols.

Example

“Your situation reminds me of other women I’ve counselled who indicated that young motherhood, with its lack of sleep, impacted their relationship and sex life”.

Some useful phrases are:

-

“Many women who ……. tell me that….”

-

“Other women with this condition tell me they’re also experiencing problems with …”

-

“Women who I monitor often tell me that ...”

-

“This reminds me of worries other women have shared with me about …”.

Cave

In this approach, always refer to multiple persons. Talking about one client can be heard as a breach of professional confidentiality between the midwife and the client. That can instil worries about her story being shared with the next woman.

Sometimes there’s no concrete reason for the midwife to worry about sexuality, but her professional instincts tell her that this woman might be experiencing sexual problems. When this is the case, the midwife could directly voice her intuitions, but the chance that this will be met with resistance from the women is great.

Case Example

Your client has just given birth, and contraception has probably not been addressed yet during pregnancy. Quickly getting pregnant again seems unwise. You’re worrying if she’s using contraceptives. You would like to bring up contraception during your next consult.

Directly voicing your concerns: “I’m worried if you’re using contraception as I’m not sure it’s a good idea to get pregnant again at this time.” could be met with resistance. The woman can experience that as addressing her reproductive and sexual habits directly and without good reason and as crossing a personal boundary without her permission. Such an approach could provoke insecurities like “what does the midwife think about me? How does she see me? It could even provoke insecurities or anger at what seems to be a judgement of their way of life: “Is this even your business? I don’t care what you think I should or should not do. You think I can’t handle another child. You just wait. I’ll show you”.

One can make this line of questions feel less aimed at them as a person by not yet posing questions directly:

Midwife (referring to professional knowledge): “We know that many women who have recently given birth need time to get their lives back on track, juggling new maternal, social, and financial worries at a trying time with lack of sleep, etc. Because of all this, thinking about contraception can easily be forgotten. Would it be okay with you if we discuss this?”

An Alternative Phrasing Could Be:

Midwife (referring to professional experience): “I’ve counselled multiple women who unwillingly got pregnant again soon after giving birth. Due to the rigours of motherhood, the lack of sleep, etc., they forget about using proper contraception. Many of them had a hard time coping with the pregnancy. You’ve just given birth yourself. Would it be okay if we discussed contraception and family planning a bit?

By referring to both knowledge and experience, sexuality is introduced as a theme connected to midwifery care in a non-personal way whilst simultaneously recognising that women might not be alone in experiencing sexual difficulties at this time. Recognising their situation can be a relief when sex is still a theme of shame and guilt. The added implicit message is that talking about sexuality is a normal part of midwifery care and that the woman can call on you when worrying about sexuality.

3 Step 1 B: Ask for Permission

After proactively introducing the theme of sexuality on a general level, the midwife will ask permission to further discuss this topic on a personal level. Asking for permission is a technique of motivational counselling that reduces the possible unwillingness to talk on the client’s side. It is a potent communication technique, giving the client co-ownership of the conversation, and letting her decide how to proceed.

Some examples: “Would it be okay for you to discuss this together?”

“Would it be okay to stay with this topic for a bit?”

“Would it be okay for you if we take some time to discuss this further?”

“Would it be okay if we take some time to talk about it and see how you are experiencing this?”

Asking for permission also means that the clients have the option of refusal; in other words, they could say “No!”. When a woman doesn’t want this conversation, you offer her a way out of a difficult situation by asking permission. Still, refusing to talk about sexuality is also important information and could be an opportunity to discuss why sex is such a difficult topic.

You can do this fairly simply by asking: “May I ask why you’d rather not talk about it?”. Even this way of exploring the issue holds a form of asking for permission. She can still indicate she does not want to go into it any further. Sometimes clients raise questions about professional confidentiality at this point. In such cases, some information about how to handle professional confidentiality can suffice to put the client at ease to open a conversation.

4 Step 2: Have the Client Tell Her Own Story

With permission to continue, the conversation moves to step 2. This step aims to get to know this client’s unique situation and experiences concerning sexuality. So, ending step 1 with permission to continue is essential.

What follows is a framework for stimulating the client to tell her story. The midwife’s change towards a genuine not-knowing stance and active listening position is more important than which questions to ask. Take in as much as possible of the client’s story without making assumptions about her experiences, thoughts, feelings, etc. That might sound evident, but it isn’t always as easy. Trained to help people, we HCPs often translate that into taking action, giving advice, sharing tips and tricks, and even getting actively involved to facilitate change. HCPs often forget that active listening should start from a not-knowing stance. Seeing the woman as the expert on her own story, her life, and her problems is essential for creating positive change.

The fact that listening helps isn’t because it solves the client’s problems, but it can relieve the client from excessive emotional burdens (feelings of shame, guilt, loneliness, etc.). Think about the woman who can finally share her frustrations about not getting pregnant for months on end without having to fear judgement. Such a conversation won’t directly facilitate pregnancy but feeling that one can share in a safe environment enables the client to unburden herself, which is already helpful. Ironically HCPs often refrain from talking about sexuality because they don’t have readymade advice or answers to offer and thus feel they can’t “help” in this respect.

The reasoning behind this step can be found in the PLISSIT Model. Annon, formulating that model in 1976, emphasised the importance of permission-giving: making clear to the client that it’s okay to talk about sexuality with you [1]. Feeling one can finally share their sexual burdens or concerns is helping because it creates recognition of those worries and has a potential normalising effect. In 2007, Taylor & Davis further stressed the importance of the impact of permission-giving on creating change through communication. Their EX-PLISSIT model put asking for permission as central to every level of the PLISSIT model, rather than seeing it as just the start of the process [6]. In the Ex-Plissit model, the HCP asks for permission when informing about sexuality, when offering helpful suggestions to the client, and when engaging in intensive therapy. This constant process of asking and receiving permission, along with a continuous form of self-evaluation and reflection on how the process is going, ensures that clients feel at ease talking about a “difficult” topic, such as their sexuality.

For many women, sexual life is taboo, with feelings of shame and guilt mostly kept to themselves. By actively listening from a not-knowing stance, the midwife stands next to the client, a woman with a unique situation and history. How does she experience her situation? What are her primary concerns? Based on what information does she make decisions regarding her sexual health and well-being? Does she require additional information? Does she need help? In short, on top of the helping effect of just listening and not judging, this step provides an opportunity to understand the client’s situation, concerns, and feelings so the midwife can formulate an appropriate intervention based on the client’s story in step 4.

The core of step 2 is adopting the not knowing stance. The goal is to recognise the client as the expert on her own story. That will enable her to tell her unique story to the fullest. As stipulated before, many HCPs refrain from talking about sexuality because they feel they lack knowledge in this area. Typically, a less professional background in sexology makes it easier to adopt a not-knowing stance when talking about sex with clients. For instance, if you don’t know about sexuality in a different cultural setting, you can genuinely ask:

Examples

“Could you tell me how you see this as a Muslima? How do your culture and your religion view sexuality? How do you deal with that in your personal life?”

Or: “How do you experience thinking about having children with a female partner? How do you feel about your partner getting pregnant?”

The more knowledge and experience one has gathered, the faster one makes assumptions based on recognisable aspects of the client’s story. It is a pitfall to unconsciously view these assumptions as being the client’s reality, without asking if your assumptions are correct.

Example

Working at a hospital’s fertility clinic and meeting a couple trying to conceive, the midwife asks: ‘Do you have sex when your chances of conception are highest each month?’. Often couples answer: “Yes!”. The midwife then writes down the answer on her intake sheet without knowing if the couple understands enough about the menstrual cycle and the fertile window.

Adopting a not-knowing stance is easier if one remembers that each woman has a unique personality, history, sexual history, and sex life. Precisely the uniqueness of her story is what the midwife needs to offer adequate help in step 4.

Once you have learned to adopt the not-knowing stance, you still have to know which questions to ask and how to ask them to make the woman tell her unique story. Step 1 had a general point of concern on bringing about a conversation on sexuality in a less direct manner, ending in the woman’s permission to continue talking about sexuality. Step 2 starts with exploring if the general concern linked to sexuality is experienced similarly by her.

Example

“Do you recognise this? How do you experience this?

Is this causing problems for you too? In what way? ...”

Step 2 focuses on exploring the woman’s unique perspective. Adopting a not-knowing stance, the HCP can stimulate the woman to tell her story with different frameworks. Within the “1 T1”-model, we propose to use the ICE framework or the BioPsychoSocial model.

The ICE technique is the first framework for exploring the client’s sexual story [3]. ICE stands for Ideas, Concerns, and Expectations. The midwife inquires about what the woman worries about (− Concerns -), if she has any idea how this came to be (− Ideas -), and what she expects of you as a HCP with regards to these concerns (− Expectations -). These questions help focus the conversation on the woman’s unique story, experiences, and needs. This line of questioning also contributes to developing a better HCP–client relationship, with the woman telling her story and the HCP understanding her experiences [3].

Ideas: This question explores the woman’s views on how her sex life has become as it is now. How does she feel about her current situation? By actively inquiring about this, the HCP will often get information that otherwise could have been excluded from the conversation. It also enables the HCP to identify a lack of or even wrong information or knowledge from the woman’s side that the HCP can attempt to correct in step 4.

Example

“What do you think is the cause of this? Do you have any ideas as to what this is related to? … ”.

Concerns: Asking about the client’s concerns is relevant because HCPs presume to know what women in this situation need or want. That can lead to an unsatisfied client when the treatment does not focus on her primary concerns. For example, a woman with dyspareunia might not focus on less pain, but on regaining intimacy, like kissing and sitting together. If we presume the pain is the current primary focus, our treatment plan might be ineffective because the woman might not be motivated to address the pain at this point.

The woman’s concerns may be different or more severe than the HCP imagines. Or the woman might arrange her priorities differently than the HCP saw in previous women. By actively asking about the woman’s concerns, the HCP breaks free of any preconceptions and adopts a genuine not-knowing stance. Asking about her concerns and asking about her priority of concerns will give the HCP a more accurate picture of the woman’s needs. In that way, the HCP can propose a tailor-made intervention in step 4.

Example

“About what are you most worried?” “What is the most important thing you hope could change?”

Expectations: Asking about expectations gives the HCP an idea of how the woman wants to see change occur. Trying to formulate this positively by asking about hope, she can again help tailor an intervention in step 4. Asking about her expectations towards you, as her HCP, will enable meeting the woman’s needs more accurately and assessing if her expectations are realistic. Such a line of questioning makes the client feel heard and creates a connection that makes it easier to correct unrealistic expectations if they would arise.

Examples

“How do you expect this to evolve in the future?” “What do you expect will happen if nothing changes?” “What do you hope to reach?” “How do you hope this can change in the future?” “What do you hope and expect me to do as a midwife?”

Additionally, it can be very worthwhile to ask the woman about her Ideas, Concerns, and Expectations related to sexuality and her sexual life. What are her ideas about having sex after giving birth? Does she expect to resume vaginal intercourse quickly? Does she expect it to be the same or different, or maybe painful? Is she concerned about how her partner will experience this period or what her partner will expect of her?

The BioPsychoSocial or BPS model forms the second usable framework [4]. This model approaches sexual health, just as general health, as the product of a delicate balance between a person’s biological or physical, psychological, and social self [4]. Again starting from a not-knowing stance, the midwife explores possible imbalances in the woman’s physical, psychological, or social/relational well-being. Such a line of questioning facilitates a broader picture of the woman’s possible distress or hindrances. That does not mean the HCP must formulate an intervention for each dimension. Interdisciplinary referrals often are necessary.

Biological or physical impact: “Does this cause any physical hindrances? Are you experiencing pain anywhere? Do you feel that this also impacts your body? In what manner?”

Psychological or mental impact: “How are you dealing with this? What does this do to you as a person? What thoughts or feelings does this bring to the surface? How do you cope with this?”

Social or relational impact: “How is your partner handling this? Does this affect the relationship with your partner? Can you find support in your social circle? How does your family respond to this? How is this viewed in your cultural/religious community?”

It’s equally important that our view of the woman’s reality is not too problem-focused. The midwife can prevent this by inquiring which aspects of the woman’s sexual life are (or are still) okay or even good. A good starting point could be questions like “What’s still going well sexually?” “What makes you sexually content?” “What still makes you happy sexually?”

4.1 How, Where, and With Whom to Have the Sex Talk?

Compiling two lists of proper and improper midwife questions about sexuality is absurd. One can train oneself to reflect critically on what to ask clients by adhering to a simple rule of thumb: What is my intent? Why am I asking this question? We should not ask sexual questions out of personal interest or curiosity. Sexuality questions unrelated to improving the woman’s or couple’s health are inappropriate. Asking about sexuality needs to start from the professional intent to monitor and enhance her or their sexual health.

Example

The woman you’re monitoring is now in the third trimester. Curiously asking if her orgasms feel different (tonic instead of clonic) is not the primary concern about her sexual health. A correct starting question about sexual health could be:” How do you feel about your sexual life during this final phase of the pregnancy? Is this something you would like to talk about?”

HCPs regularly use non-health-related themes as connection catalysts to develop a good working alliance with the client. However, to build a trusting relationship, we better not choose sexuality since that is, for many people, still a taboo subject, evoking feelings of insecurity, shame, and even guilt. There are plenty of other positively connotated themes to use.

Since the topic can also be complex for the midwife, it might be good to ask where and with whom sexuality should be discussed.

Sexuality is a part of our individual lives and part of our connected lives. As an individual, we have sexual ideas and feelings. Our bodies respond uniquely to sexual stimulation, and we have our private sexual life (for instance, fantasies or masturbation). That changes when we look at sex as part of our connected life with its interpersonal dynamics. Sexuality is integral to the dyadic relationship between both partners in a couple. Even in a sexual encounter with a “one-time” partner, sexuality is part of the interplay between those two people. Realising this emphasises the need to inquire about the context in which the woman experiences her sexuality. Solo or partnered? Within or outside a committed relationship? With a man, women or non cisgendered other? We cannot view the sexuality of a woman in a committed relationship as independent from her partner’s sexuality. So, if possible, it will benefit to (also) talk about sexuality with both partners present. However, for some women, talking about sex with their partner present is more complicated than a one-on-one conversation with the midwife. That might be due to sexual problems, relational problems, feelings of shame or guilt, sexual abuse, etc. So, again, don’t force the sexuality theme onto the client but start the conversation in a non-personal manner and by asking the client’s permission. Sometimes a woman might first prefer a one-on-one conversation with the midwife, drawing strength from that conversation to, later on, talk about sex with her partner present. Starting by asking the woman’s preference on “how and with whom to talk about sex” can be helpful:

Example

“I’d like to address sexuality. Would you prefer that now, or would you like to postpone that till next time when your partner is also present?”

Even without being present, the partner’s perspective can actively be incorporated into the conversation. For instance, by asking: “What does he do?” “Do you know his ideas about your current sex life?” etc.

Some example questions might be:

“You’ve told me that now that you’re actively trying to conceive, you sometimes feel like having sex is a burden rather than a joy. How do you think your partner is experiencing this?”

“You told me you prefer waiting after the birth until you feel completely ready for intercourse again. What ideas do you think your partner has on this?”

While the answers on her partner’s sexual experiences might seem second-hand and sometimes not correct, asking about the absent partner will at least trigger the client to consider how her partner is experiencing their current sexual relationship.

The context. Almost all clients prefer to discuss sexuality without being overheard by other people. That sometimes seems impossible to do. We might only be separated from the next woman by a hospital curtain. Many women are admitted to an open ward. Such a lack of privacy might hinder clients from talking about sexuality. When the woman is hesitant, actively remarking on these difficulties might benefit the conversation and the connection with her.

Examples

“It is my midwife’s job to monitor your general health and well-being, including sexual health. Would it be okay for you to talk about that?”

When the woman hesitates to answer and remains silent: “Many people feel more comfortable talking about sexuality in a more private setting. Is it okay for you if we pick up this topic at another time?”

Or: “Many people feel more comfortable talking about sexuality in a more private setting. Would you feel more comfortable talking about this in a more private place?”

Of course, the physical reality of our work accommodation can hinder us. Midwives can deal with such situations creatively. Some clients might prefer to write their questions down, get a written answer, etc. Discussing sex while walking through the hospital together might feel more comfortable than in their room, where other women or staff are eavesdropping.

5 Step 3: Summarise

This third step is relatively short but of great importance. It forms the bridge between the woman’s story and the midwife’s attempt to respectfully round up the conversation, moving towards formulating an offer of assistance.

Respectfully rounding up a session is essential, even more so with the touchy subject of sexuality. As most people seldom talk (to HCPs) about sexuality, ending such a conversation with care can be done by the simple but powerful basic communication skill that stems from motivational interviewing [2]: summarising.

With a good conversation summary, the woman will understand that you attentively listened to her story. It structures her story and provides a way to emphasise certain of its aspects. Besides, it enables you to retake control over the conversation, easily change the direction of the conversation if needed, or just round it up respectfully.

The midwife attempts to capture the essence of the woman’s unique story, which is her lived reality. Summarising should be based on the answers given by the woman on the ICE or BPS questions. Then check if you have correctly summarised by asking: “Did I get that right?”. Using closed questions gives the conversation control back to the midwife if necessary.

Example

“Okay. If I understand it correctly, since the treatment for your endometriosis, you have less sexual desire. That isn’t bothering you much, but it hurts when you have intercourse with your husband. You worry about how your partner experiences this situation. Did I get that right?”

Step 3 summary |

− Summarise: Repeat the essence of the answers to the ICE questions; or Repeat the essence of the answers to the BPS questions − Check: “Did I get it right?” − In case the partner is absent: “Do you think your partner will agree, or do you think he would change or add something? |

− Types of summarising: Summarising = Respectfully rounding up the conversation whilst making the client feel heard Summarising = Giving back the client’s story in a more structured way Summarising = Retaking control of the conversation |

6 Step 4: Make an Offer

With this final step, the circle is made whole. After summarising, the woman hears that the midwife has been paying attention. Still, the question of how to move forward remains unanswered. In case an intervention is needed or desired by the woman, the HCP offers the possibility of an intervention tailored to this unique woman’s specific story and expectations.

HCPs should realise that having addressed sexual concerns or problems is sometimes enough. It can also be enough for the time being since creating change might need a long process. Besides, some conversations will not contain concrete interventions, providing already the required intervention.

The midwife can propose various interventions when the woman needs or desires concrete interventions. Examples are a treatment within the midwife’s expertise, tailored psychoeducational information, a subsequent appointment for in-debt handling of the woman’s story, or referring to a colleague with more expertise.

6.1 A Treatment Proposal, Based on the Midwife’s Expertise

If your conversation with the woman clarifies that she is worried about aspects of her sexual life, and if you, as a midwife, can present a solution in the form of treatment, this can be part of step 4. For example, you are prescribing a contraceptive during the postpartum period (e.g. one that does not negatively impact the woman’s sexual desire and arousability). In many situations, adequate psychoeducation or targeted interdisciplinary referrals are necessary to handle sexual difficulties successfully.

6.2 Giving Information

Once they feel their story has been heard, many women and couples benefit from adequate psychoeducation. Information such as how specific pathologies (e.g. mastitis or hyperemesis) or situations (e.g. young motherhood) can impact sexuality often normalises what women are experiencing. Such a normalising effect diminishes negative emotions surrounding the problem, thus helping the woman achieve positive change. That does not mean that HCPs should have all the necessary information ready in their minds. Guiding people towards accurate books or online information is sometimes enough to alleviate a problem. It’s a challenge for many people to find online understandable and trustworthy sexuality information. Actively exploring the woman’s ideas on sexuality in step 2 can indicate if she lacks specific sexual knowledge or holds wrong beliefs on aspects of sexual functioning. Then try correcting the erroneous beliefs as they can be part of what’s causing the sexual difficulties. Sometimes this can be enough for women to make the rest of the necessary positive change happen themselves. The midwife should be aware of reliable sources of information in the woman’s language. A very reliable, multilingual online source is the webpage www.zanzu.be.

Zanzu has been developed by Sensoa, the Flemish Expertise Centre of Sexual Health and HIV. It has information on sexual health, reproduction, sexual problems, and family planning.Footnote 2 It is a good point of reference for HCPs all over the globe. Symbols and drawings on the website facilitate navigation and understanding of the information. The information is available in 14 languagesFootnote 3 and can be played as audio files spoken by native speakers. Zanzu can be used during a session with the woman listening to accurate sexual health information, whilst you can, in your HCP language, strictly follow what the woman hears. Such an experience can strongly impact the relationship with the woman, especially when confronted with cultural and language differences.

6.3 Planning a Follow-Up Appointment

When women talk about their sexual concerns for the first time, it could very well be possible that they cannot tell their whole story in step 2, especially given the time constraints that can be in place in different healthcare settings. Planning a follow-up conversation to explore the woman’s story can be a valuable intervention. Talking about concerns and worries and feel listened to is essential for any treatment process.

6.4 Make an Offer for an Interdisciplinary Referral

Some sexual problems require treatment beyond the scope of the skills and knowledge of the midwife. Perhaps the woman or the couple needs sexological or psychotherapeutic treatment. Treatment by a clinical sexologist, psychosexologist, or psychotherapist trained in sex therapy should always be tailored to the sexual difficulties of the unique woman, her needs and her hopes. Such treatment deserves a biopsychosocial approach and a “couple approach”. Sometimes a referral to other medically trained professionals is needed, such as the gynaecologist, urologist, endocrinologist, or pelvic floor therapist, to treat or rule out possible physical causes for the sexual disturbances. Midwives should develop a network of professionals from various disciplines with practical knowledge of treating sexual problems. To successfully treat the more complex sexual troubles, we all require interdisciplinary collaboration, with mutual fine-tuning and open communication between the various professionals.

7 Conclusion

As long as sexuality remains taboo, women, couples, midwives, and other HCPs might find this a complex topic to tackle in the conversation. The “1T1” model makes the task of “talking sex” easier by providing a clear framework for the midwife. This model neither requires much working knowledge on sexual health, nor uses up much time. By giving multiple examples within each stage of the model—raising the issue proactively, encouraging the women to tell their story, summarising, making an offer—on how to phrase questions to get the conversation going and how to keep it going, we hope that more HCPs will talk sex and that the woman, the couple, and the HCP will stay behind feeling that this was after all “just another part of the conversation”.

Notes

- 1.

SENSOA is the Flemish Expertise Centre for Sexual Health and HIV prevention. As part of their focus on enhancing the sexual well-being of the community as a whole, a model was developed to help general practitioners engage more easily and often with their patients on sexuality. This chapter explores the usability of that same model for midwifery practice.

- 2.

Among the topics are: the male & female body, sexual pleasure, having sex, virginity, hygiene, the sexual body, contraception, getting pregnant, being pregnant, sex during and after pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy, giving birth, young parenthood, STIs, HIV, vaginal infections, condom use, sexual problems, romantic relationships, talking about sex, couple problems, and intimate violence.

- 3.

Albanian, Arabic, Bulgarian, Dutch, English, Farsi, French, German, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, and Turkish

References

Annon JS. The PLISSIT model: a proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. J Sex Educ Ther. 1976;2:1–15.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 2013.

Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36.

Borms R, Vermeire K. Spreken is goud: Seksuele gezondheid bespreekbaar maken met de Onder 4 Ogen methode. Ontwikkeling en implementatie bij huisartsen in Vlaanderen. T v Seksuologie. 2020;44:155–61.

Taylor B. Davis S using the extended PLISSIT model to address sexual healthcare needs. Nurs Stand. 2006;21:35–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Borms, R., Geuens, S. (2023). Talking Sexuality. In: Geuens, S., Polona Mivšek, A., Gianotten, W. (eds) Midwifery and Sexuality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18432-1_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-18431-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-18432-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)