Abstract

We tend to think of flourishing as a place we get to, where we have arrived, but often do not see that act of change itself is a core facet of what it means to flourish. Indeed, we argue that flourishing is in fact our ability to change and adapt rather than a state that we are striving for. This points to human flourishing requiring an ‘adaptive’ approach to manage change: supporting careful navigation, negotiation and trade-offs. On this basis we need to identify the barriers that get in the way of enacting these possibilities and as such organisations and institutions that seeks to facilitate behaviour change will lean on barrier identification as well identifying ways to overcome them thought educating, assisting and facilitating. Using a behaviour change framework to identify the mechanisms shaping behaviour can help to identify ways to overcome barriers and facilitate positive outcomes.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s personal opinion and do not represent the official views, strategy or opinions of Ipsos or Nottingham University Business School.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

What do we need to flourish in life? This is a topic that has gripped philosophers, policymakers, business strategists, parents, lovers and friends since time and eternity.

This chapter is a call-to-arms for what can seem to be a forgotten part of flourishing: that of enacting change. Whilst we tend to think of flourishing as a state of being, a place at which we have arrived, we can often fail to see the way in which the act of change itself can be seen as a core facet of what it means to flourish.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold suggests that we are continually reviewing, anticipating, changing not only as we learn and understand but as the external environment around us changes. He writes that ‘where there is human life there is never anything but happening. Life is not; it goes on’. He suggests that we are not in fact human beings, fixed in time, rather that we are all always life-in-the-making and as such we could call ourselves ‘human becomings’. The ability to ‘become’ is therefore how we might define human flourishing, it is our ability to change and adapt rather than a state that we are striving for (Ingold, 2021).

The poet John Keats used the term Negative Capability to describe the skills and strength needed to manage this transformation, describing the state as being ‘…when a man is ‘...capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’ (Keats, 1899).

We set out a number of complexities involved in thinking about behaviour change: how the desired behaviours are not always obvious, but also how the environment we are in can challenge our ability to enact those behaviours. Also, how our choices of behaviour are acts that occur in a human social, cultural context, and it often is this which grants it meaning and imaginative possibilities.

Given change is at the heart of flourishing, we then consider ways in which organisations and institutions can help facilitate change. This requires us to adopt an approach that mediates the complex interactions between people, the environments they operate in and the way in which desired outcomes can be enacted. This very process is one which we can consider to be human flourishing.

1 Flourishing and Behaviour Change

There is a case for the act of change itself being at the heart of flourishing, but what is the change directed towards? To understand this we need to explore the way wee have a strong drive for meaningful lives, driven by our imaginations.

1.1 The Drive for Meaning

Since Aristotle, there have been many ways in which we might think about what flourishing means. Philosopher Susan Wolf offers a ‘Fitting-Fulfilment’ view of flourishing, suggesting that indulging one’s passions offer a particularly rewarding type of subjective experience, but this is not in itself what is valuable (Wolf, 2012). The thing we love doing must also be ‘objectively good’. And this is in partly to do with a need that we can see one’s life as valuable in a way that can be seen from another person’s perspective.

Our drive for this is due in part to our need to see ourselves from an objective, external perspective. As Thomas Nagel would say, we are unique as a species in that we are able to have a ‘view from nowhere’ upon ourselves (Nagle, 1998). In addition to this, we have a need for self-esteem. We want to be able to see ourselves as good and valuable.

We might add to this, considers Wolf, in this way:

The thought that one’s life is like a bubble that, upon bursting, will vanish without trace can lead some people to despair. The thought that one lives in an indifferent universe makes some people shudder.

If we can think of ourselves as being engaged in a behaviour of independent worth, then we may be able to put aside these feelings of despair. The feeling of being involved in a behaviour that has value, independent of our own narrow self-interests, means we become part of a community, sharing values and a common purpose. As Wolf puts it:

By engaging in projects of independent value, by protecting, preserving, creating and realizing value the source of which lies outside of ourselves, we can satisfy these interests. Indeed, it is hard to see how we could satisfy them in any other way.

Our desire for a meaningful life is not about feeling a particular way but an interest that life be a certain way, one that can be admired by others and is connected in some way with independent value. Philosopher Lucas Scripter reminds us not to interpret this in a manne that is overly ‘elitist’; as he points out, not everyone is cut out to be a Steve Jobs or a Jane Austen. Rather, meaning is as much reflected in ‘ordinary meaningful lives’ involving personal relationships and aesthetic experiences (Scripter, 2018).

Nevertheless, the point we can take from Susan Wolf is the drive for meaningfulness which has an active component: behaviours need to take place. To flourish, it is not enough to dream, there needs to be action, as Goethe famously pointed out:

Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do

This is consistent with philosopher Agnes Callard’s perspective when she points out in her book about change, ‘Aspiration’, that:

Valuing involves more than caring: when we value something, we also evaluate it as in some way good or worth caring about. (Callard, 2018)

We can perhaps take this to mean that our values shape what we choose to engage with, they also motivate us to shape our behaviours in relation to it.

1.2 Imagined Futures

The question that is surely raised is how we construct a sense of ways to achieve meaningful lives. This feels close to the issue of sense making that psychologists Nick Chater and George Lowenstein consider is analogous to better known drives such as hunger, thirst and sex (Chater & Loewenstein, 2015). Sense making seems an ever more important challenge to get right, given that the world we now live in is vast, interconnected and complicated. As such ways in which we can consider ways of living as different to that we experience today means we need to use imagination to look at future possibilities.

One of the early people that worked on the psychology of imagination is Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky who considered imagination was at the heart of much of human life. He considered it a creative, higher order mental activity and “the essential feature…that of imagination is that consciousness departs from reality. Imagination is a comparatively autonomous activity of consciousness in which there is a departure from any immediate cognition of reality” (Vygotsky, 1987). In other words, this gives us a degree of freedom from the restrictions of our immediate situations.

But linked to this is the way in which imagination is also deeply linked to our social reality. Vygotsky set out how the human mind is shaped by historic and cultural forces. As Tania Zittoun and Alex Gillespie put it more recently (Zittoun & Gillespie, 2015):

It is an obvious, but revealing, fact that for the vast majority of human history it was impossible for people to imagine space travel, intelligent robots, or even telephones. The earliest attempts at such imaginings seem limited, and saturated with the culture of their time.

Imagination is therefore not a solitary activity; we have the ability to build imaginative possibilities with others but also our acts of imagination can shape the society and culture they draw from. As such:

It is the fundamental process by which we can explore and share our past—individual and collective, define and visit alternative and possible worlds, and imagine the future—our own, and that of the world—and perhaps, set us in motion toward it.

We can see that part of flourishing is the ability to use imagination to consider future possibilities, working on ways to prospect, or ‘construct’ our lives. As Wolf points out, supporting people to place their behaviours into a wider network of meaning and sense is hugely motivating for people. This meaning is all about prospecting the future, seeing how we can be part of something bigger than ourselves, shaping a future that we would wish for ourselves and others.

This points to humans requiring an ‘adaptive’ approach to manage change: careful navigation, negotiation and trade-offs. This adaptive approach suggests that we need to identify the barriers that get in the way of enacting these possibilities and as such organisations and institutions that seek to facilitate behaviour change will lean on barriers identification as well identifying ways to overcome them through educating, assisting and facilitating.

2 Dimensions of Navigating Change

At the heart of flourishing is an intense relationship between intention and behaviour: we may know what we need to flourish but we do not properly flourish until we start to enact change. There are complexities and barriers to changing behaviour which are characterised here in three broad ways: internal barriers of understanding the difficulties of making change when the outcomes are not always apparent; the barriers related to the situation we are in which is increasingly fluid, meaning we can struggle to work out how to enact and maintain desired behaviours and then finally the social and cultural barriers, managing the negotiation of meaning in our socially embedded lives.

2.1 The Internal Barriers Challenge

The psychologist Kurt Lewin talked about the way in which change requires us to first ‘unfreeze’ our mental landscapes. If we remain fixed in the ways we approach the world, then we leave no opportunity for change. But once unfrozen, do we always know what we want and how we want to flourish? What we are aiming for can often be unclear as Rebecca Solnit points out in her book, ‘A field guide to getting lost’ (Solnit, 2017):

The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation. Love, wisdom, grace, inspiration—how do you go about finding these things that are in some ways about extending the boundaries of the self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else.

Again, Agnes Callard also talks to this theme of uncertainty of transformation when she suggests:

The aspirant’s idea of the goodness of her end is characterized by a distinctive kind of vagueness, one she experiences as defective and in need of remedy.

This type of change is harder than a related theme, ‘ambition’, which Callard describes as follows:

An ambitious agent’s behaviour is directed at a form of success whose value she is fully capable of grasping in advance of achieving it. Hence ambition is often directed at those goods—wealth, power, fame—that can be well appreciated even by those who do not have them.

Surely for a human to unfreeze and flourish then we surely need to think of this in terms of ‘aspiring’ rather than ‘ambition’. There is a period of intense uncertainty where we try and work out the direction we take. Indeed, when we embark on a venture of transformation that enables us to flourish, Callard would likely argue that people are usually aware that they will change in ways that are impossible to know and hard to understand. There is no one single point, rather a period of continuous change:

When one makes a radical life change, one does not submit oneself to be changed by some transformative event or object; one’s agency runs all the way through to the endpoint. The nature of that agency... is one of learning: coming to acquire the value means learning to see the world in a new way.

This suggests that if we ‘aspire’ to flourishing, then we are continually reviewing and anticipating, changing not only as we learn and understand but as the external environment around us changes. There are a whole range of ways in which different aspects of ourselves may therefore be barriers to change. These might include identity: the sort of person we see ourselves as; outcome expectations: the way we see risks associated with certain behaviours; emotion: whether we feel anxious and fearful or bold and excited. Alongside these motivational considerations is our ‘capability’—ensuring that we can benefit from education to understand the possibilities, barriers and how we can overcome them. These and other dimensions are part of the ways in which our individual orientation can shape our response to change.

2.2 The External Barriers Change

As we well know, our environment can sometimes change dramatically. COVID is an example of a dramatic change that was imposed on us. Suddenly we have had strict curtailing of a wide range of activity that we once considered normal. Many of the routines we had acquired to manage our world were, very quickly, no longer relevant as they had offered us mastery of a world that no longer exists. We were collectively and rapidly ‘unfrozen’, to navigate a very fluid situation.

We can place this in a wider context of a changing environment by referencing Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman who suggested we live in ‘liquid times’ where thinking, planning and acting deteriorate over the long term (Bauman, 2007). He suggested that our environment is increasingly subject to a state of change and operating without fixed, solid patterns. This means that we must learn to ‘walk on quicksand,’ being flexible and adapting constantly to rapid change.

This era of uncertainty is not a temporary stage, he suggests, but inevitable and permanent which means that people will have even more to worry about in the future. That is why it is important for them to have the tools to cope with uncertainty. German sociologist Hartmut Rosa refers to ‘social acceleration’, or ‘the shrinking of the present’, making reliable expectations of the future increasingly problematic and fluid (Rosa, 2015).

All the while, this is against a backdrop of more liberalisation and privatisation that have increased the variety of products and services on offer in finance, health care, insurance, pensions, education, and energy supply. We are all expected to make informed choices out of a wide range of complex products and services.

The implication of this is that people must be increasingly self-reliant, working out how best to navigate increasingly complex environments and, within this, working out how to steer towards our own ends that may often be vague and unclear.

So it appears that the environment we are in sets up a range of challenges for us—some of which may be out of our control. We seek to find ways in which to mitigate these challenges and where possible re-structure the way in which we engage with these environmental barriers.

Another element is the social and cultural context. As Wolf has pointed out, meaningful behaviours do not sit in a vacuum—they are only given meaning and purpose through understanding the interchange between the human inner life and the social context. As such, theories which seek to find explanations of human behaviour by leaning on notions of automaticity, may struggle to account for a full understanding of when, where, how and why humans seek meaning and a desire to flourish in their lives.

Philosopher Mary Midgley referred to this when she wrote:

Social institutions such as money, government and football… .are forms of practice shaped and engaged in by conscious, active subjects through acts performed in pursuit of their aims and intentions. They can therefore only be understood in terms framed to express those subjects’ point of view. (Midgely, 2006)

One of the important aspects of considering behaviour change is that the wider, socially embedded aspects of our lives cannot be ignored. As Wolf points out, an understanding of the context in which the behaviour is embedded is critical—behaviour never takes place in a vacuum. We can see how that is not only a function of our own internal characteristics (our motivations, capabilities) but also the physical, social and cultural environment we inhabit.

2.3 Internal Meets the External

Humans occupy a space which necessarily integrates the external and the internal—the way in which we process information and then enact behaviour is at the heart of much debate within psychology. As such it is worth setting out some of the parameters of the discussion.

The discipline of psychology has, arguably, tended to focus on past experiences as a determinant of current and future behaviour. On this basis we can see the way in which the external environment that we inhabit can then be seen as having primacy in determining our behaviour.

Indeed, much of the history of psychology has been accounted for behaviour arising as a result of historic causality. Early behaviourists assumed that human activity could be understood with animal experiments, and that our behaviour is largely the result of stimulus and responses that we have been exposed to in our pasts. The evidence for this came from animal studies where experimenters observed that rewards or punishments could be used to shape certain behaviours, such as rats choosing which direction to travel in a maze. Human behaviour was thought to be no different, even though the mechanisms underpinning behaviour may be more complex.

This approach started to be contested as it become clear that the tested animals’ behaviour could not always be fully explained using simple ‘stimulus-response’ theory. There were novel behaviours (such as rats taking shortcuts or swimming in the right direction after their maze was flooded) which suggested that animal behaviour was, in fact, more prospective and adaptive than initial stimulus-response theorists, who expected the animals to flounder in unencountered circumstances, would have believed. The animals had demonstrated some capacity to mentally engage with the task and at some level consider future possibilities differently to the manner their associations would logically have led them (Seligman et al., 2013).

A ‘teleological’ alternative to the ‘past oriented’ tradition started to emerge, meaning the explanation of our behaviour can be understood through the outcomes that we are seeking rather than purely being determined by our past experience. Martin Seligman is one of the leading proponents of a ‘prospective’ orientation to understanding human behaviour (Seligman et al., 2013). He considers that we construct an evaluative landscape of possible acts and outcomes which is used to guide our behaviour.

Of course there is not a binary distinction between these meta-accounts of human behaviour, one which references external factors in the shape of past associations, and the other of which cites internal characteristics in the shape of future prospecting. Inevitably, both have their place in helping to account for different types of behaviour. Indeed, we do not necessarily see them as entirely separate accounts, as the evaluation of the future clearly leverages our learning and memory of past experience. We have also seen the way in which our internal lives are shaped by external cultural narratives of what is possible. We need to understand the nature of the subtle inter-relationships between these two broad ways of considering human behaviour, if we are to support people to change.

3 The Principles and Practices of Behaviour Change

We can see the way in which change has both individual, contextual and social components to it which are often characterised by uncertainty. Understanding this and how we rise to the challenge of navigating this and helping others to do so is key to making change happen. Psychology offers us a way to understand many of the mechanisms that sit underneath this.

If we are to help people change, to strive for their imagined futures, then we need to properly understand what the mechanisms are that underpin the enactment of our behaviour. If we can identify these, we can then help make use of them to help facilitate people changing, overcoming the range of barriers.

How can organisations and institutions help to facilitate change and as such, human flourishing? There are a huge number of possible psychology theories that we can draw on to help identify the dimensions that shape behaviour—these all have different means by which they identify barriers (in our terms) to changing behaviour and as such are important starting point for behaviour change.

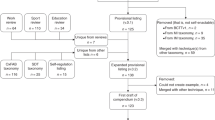

The challenge is knowing which theory to choose, as illustrated by a recent book which identified over 80 possible theories of behaviour change (Michie et al., 2014). Selecting the one most suited to a particular challenge requires wide knowledge and expertise that is not always readily accessible. In addition, and problematically for the practitioner, theories that help us understand behaviours typically do not offer guidance about which interventions to prescribe in order to actually change behaviour. Whilst understanding behaviour is important, we clearly need to be able to then help people to enact behaviour change.

To overcome these challenges, we must move away from theories of behaviour change towards ‘systems’. These are when a range of different theories have been integrated into a single ‘meta framework’ to avoid the issues we have just mentioned. This firstly means we can then use a single approach to understand the barriers to behaviour change, confident that it will offer a comprehensive view across a wide range of issues.

Secondly, systems of behaviour change point to ways in which the desired outcomes can be achieved. This is significant as many approaches are available for diagnosing behaviour, but far fewer offer guidance on how to link this through to designing interventions to change behaviour.

We use a behaviour change framework or ‘system’—MAPPS—to help facilitate this change (See Table 1 for a very simple example of changing recycling behaviours) (See: https://www.ipsos.com/en/science-behaviour-change). This involves a number of straightforward steps. The first task is Define, what is the outcome that is being sought? As we saw earlier, this is not always as simple as may first appear. We may not always know precisely what we want but rather the ‘direction of travel’.

We can nevertheless act by understanding that change is a process, drawing on stage theories such as the transtheoretical model which suggests a series of stages of readiness for change, namely: precontemplation (no intention to make changes or rejecting the need for change), contemplation (serious consideration of making changes), preparation (undertaking small changes), action (actively engaging the desired behaviour), and maintenance (continuing the desired activity). Each of these will have different considerations for how we define behaviour (Prochaska & DiClemente, 2005).

The next step is ‘Diagnosis’, a clear-headed understanding of what people find hard about change, identifying what is preventing people from being able to move to the next ‘stage’. We can think about this in the context of sustainability behaviour for example. Why don’t people recycle even when they say they want to do so and intend to do so? An ‘adaptive minds’ view of humans would suggest we first need to understand what the barriers are to enacting that behaviour; we use our framework (MAPPS) for just this purpose.

We can see from this example in Table 1, there are all sorts of reasons, both internal and external to the individual, that may inhibit the enactment of recycling behaviour.

Of course, an understanding of this is only half the challenge—we then need to move to the Design stage of behaviour change. By understanding these barriers, we can then link them to Design Principles to generate ‘interventions’ to help people overcome these barriers. Different classes of interventions that we use include:

-

Understanding: Build knowledge, help people see relevance and importance.

-

Feedback: Provide positive or negative guidance, direction, or outcome expectancies.

-

Planning: Develop and maintain intentions or skills needed to perform a behaviour.

-

Restructure: Change the environment to enhance or remove influences.

-

Connect: Allow connections to be formed or make them available as informational sources.

With this sort of approach, we can start to develop interventions that are more likely to succeed as they are directly related to an effective diagnosis of the issues, and as such we are helping to facilitate change.

These interventions can take many forms ranging from simple ‘nudges’ through to education and wider engagement types of activities. The point is that we start with the individual and an understanding of their context-based lives to unlock barriers to change and in this very process enable them to participate in the process of human flourishing.

4 Closing Thoughts

A case has been made for the way in which the act of changing behaviour is itself flourishing: it is tempting to assume that human flourishing is a position we arrive at and whilst this is surely part of the explanation, the act of being human means rising to the challenge of continuous change. It is the act of overcoming individual, environmental and social and cultural barriers that is also very much part of human flourishing.

People are less able to turn to the usual guides for behaviour whether it be the bank, doctors, media, teachers. These professions are all in a process of change themselves so the extent to which behaviour is now guided by these gate keepers is, at best, debateable.

In addition, psychologist and philosopher Matthew Crawford suggests there were historically greater social affordances in the form of close family, colleagues and friends that lightly directed us into actions that we may find rewarding and meaningful. But these societal structures are arguably giving way to more individualistic points of reference (Crawford, 2016).

Making change happen is therefore at once both more challenging than ever and yet is at the heart of human flourishing (see Table 2). Helping people to imagine futures and navigate change is therefore going to be more critical than ever.

References

Bauman, Z. (2007). Liquid times: Living in an age of uncertainty. Cambridge Polity.

Callard, A. (2018). Aspiration: The agency of becoming. Oxford University Press.

Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). The under-appreciated drive for sense-making. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126, 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.10.016

Crawford, M. (2016). The world beyond your head: How to flourish in an age of distraction. Penguin Books.

Ingold, T. (2021). Being alive. Routledge.

Keats, J. (1899). The complete poetical works and letters of John Keats (Cambridge ed., p. 277). Mifflin and Company.

Michie, S. F., West, R., Campbell, R., Brown, J., & Gainforth, H. (2014). ABC of behaviour change theories. Silverback publishing.

Midgely, M. (2006). Science and poetry. Taylor and Francis.

Nagle, T. (1998). The view from nowhere. Oxford University Press.

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (2005). The transtheoretical approach. In J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy integration (Oxford series in clinical psychology) (2nd ed., pp. 147–171). Oxford University Press. isbn:978-0195165791. OCLC 54803644.

Rosa, H. (2015). Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity (New directions in critical theory). Columbia University Press.

Scripter, L. (2018). Ordinary meaningful lives. International Philosophical Quarterly, 58(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.5840/ipq2018215102

Seligman, M. E. P., Railton, P., Baumeister, R. F., & Sripada, C. (2013). Navigating into the future or driven by the past. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612474317

Solnit, R. (2017). A field guide to getting lost. Canongate Books.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), Problems of general psychology (Vol. 1). Plenum Press.

Wolf, S. (2012). Meaning in life and why it matters. Princeton University Press.

Zittoun, T., & Gillespie, A. (2015). Imagination in human and cultural development. Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Strong, C. (2023). Human Flourishing Through Behaviour Change. In: Las Heras, M., Grau Grau, M., Rofcanin, Y. (eds) Human Flourishing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09786-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09786-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-09785-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-09786-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)