Abstract

The chapter provides a theoretical and conceptual approach to tax incentives and their desirable and problematic characteristics. It then presents the objectives that, from the international scenario, the OECD’s BEPS Project and the Sustainable Development Agenda seek from their good design and implementation. Finally, it presents the current panorama of such incentives in Latin American countries in general, and in those of the Pacific Alliance in particular, analysing, based on a sample of income and value-added tax incentives, their difficulties in meeting international standards. Finally, it proposes a series of public policy recommendations for improvement.

Lawyer, economist, and magister in economics (Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia). PhD in Law (Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain). PhD in Law and LLM in Taxation, Programme Director, Universidad de los Andes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Following Ogazón and Hamzaoui (2015, p. 8), there is tension between two tax policy considerations. On the one hand, legislatures should not have trouble in designing and implementing legislative measures against base erosion. On the other hand, policymakers need to improve the attractiveness of their countries from a tax perspective. However, the existence of a “favourable” domestic tax system facilitates tax avoidance.

The Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project is no stranger to this discussion. That is how, for example, Cotrut and Munyandi (2018) consider that “recent tax developments aimed at mitigating the possibilities of base erosion and profit shifting are expected to increase the importance and popularity of tax incentives (…) due to the fact that states will want to remain competitive on the international stage and multinational enterprises will look for the opportunities to minimise their tax liabilities” (p. ix).

For the above, one part of the minimum standard on BEPS Report Action 5 relates to preferential tax regimes, where a peer review was undertaken to identify features of such regimes that can facilitate base erosion and profit shifting and therefore have the potential to unfairly impact the tax base of the other jurisdictions. Very recently the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released a new publication “Harmful Tax Practices—2018 Progress Report on Preferential Regimes” (29/01/2019), which contains results demonstrating that jurisdictions have delivered on their commitment to comply with the standard on harmful tax practices (including the Latin American and Caribbean Countries of Barbados, Curacao, Costa Rica, Uruguay and Panama).

However, Latin American countries continue to include multiple tax benefits in their legislation. The paper will explore the situation of the four countries belonging to the Pacific Alliance (Mexico, Peru, Chile and Colombia) and will make concrete recommendations as to its justice and efficiency, in order to meet the goals, set forth in the Sustainable Development Goals and in the BEPS Project.

Given the above, this document begins with a theoretical and conceptual approach to the raison d’être of tax incentives, and the consequent tax expenditure, and their desirable and problematic characteristics. It then presents the objectives that, from an international perspective, the OECD’s BEPS Project and the Sustainable Development Agenda (SDA) seek to achieve with a good design and implementation of tax incentives. Following this, the paper presents the current panorama of these incentives in Latin American countries in general and in those of the Pacific Alliance in particular. Finally, we provide a number of public policy recommendations for improvement.

2 A Theoretical and Conceptual Approach to Tax Incentives

The first thing we need to clarify is that not all tax benefits are incentives. Some benefits are simply intended to alleviate the burden of the less privileged, as happens, for example, with the exclusion of value-added tax (VAT) from the basic family basket. As stated by Ogazón and Calderón (2018), there is no consensus on what is meant by a tax incentive. Table 6.1 lists some of the doctrine’s definitions:

The above definitions allow us to conclude that a tax incentive has the following characteristicsFootnote 1:

-

1.

Specialty and exceptionality: This refers to special and exceptional tax measures in relation to general rules.

-

2.

Favourability: This relates to treatments that seek to favour a sector or types of investment.

-

3.

Effectiveness: This seeks an objective, for example, increasing the rate of return of an investment or reducing its risks or costs.

-

4.

Economic instrument: This refers to fiscal policy instruments used to attract domestic and foreign investment, depending on the type of incentive, or to alleviate the situation of existing investment.

-

5.

Qualification: This is a process by which it is necessary to comply with some incentive requirements in order to qualify.

-

6.

Period: Usually tax incentives are guaranteed for a period of time.

-

7.

Coverage: Incentives may cover one or more taxes depending on their nature.

-

8.

Interrelation: Jurisdictions may implement different interrelated incentives depending on fiscal policy. Finally,

-

9.

Tax expense: Every tax incentive generates an expense in public finances.

There is, however, a general tendency in the doctrine to affirm that in order to encourage investment, the tax channel is not the only one possible and that it may even become ineffective. Thus, in relation to incentives other than tax ones, Tavares-Lehman (2016, p. 22) states “there is a considerable array of types and subtypes of incentives. Very often governments offer a mix, or a package, of different types of incentives. This mix or package of measures varies greatly among countries and even subnational jurisdictions”; and he delves more deeply into those financial incentives, where he analyses, among other things, grants, subsidies, loans, wage subsidies and job training subsidies; creation of new, targeted infrastructure; and support for expatriation costs (p. 22).

Munongo, Akanbi and Robinson (2017) and James (2016, p. 173) emphasise that to attract foreign investment, it is not only the tax factor that is important but also other non-tax factors, such as macroeconomic conditions, infrastructure and adequate institutional design. Laukkaanen (2018) adds the relevance of raw material costs. Carrizosa (2008) analyses how competitiveness indicators in Latin America include, in addition to tax aspects (where he recognises that there are many exemptions in Latin America, tariffs are not neutral, and many anti-technical taxes still exist in the region), political uncertainty, macroeconomic instability, corruption, access to financing, barriers to employment, infrastructure and other transaction costs in general (e.g. licences and customs). However, some studies such as those by Zhan and Karl (2016) conclude that in order to attract foreign investment, the most commonly used vehicles are financial and regulatory taxes (p. 204).

The ineffectiveness of incentives is also widely analysed by the doctrine in both general and specific ways. Thus, for example, James (2016) states, generally speaking, “tax incentives are widely prevalent and reflect the desire of the government to support economic growth and provide value for the local economy through jobs, new skills, and technology. Governments also provide tax incentives in order to diversify their economies and support activities they hope will lead to new sources of growth that use the untapped potential of the country (…) However, this had unintended consequences, resulting in increasing opportunities for rent seeking, as discretionary power can be misused” (p. 173). Also, Redonda et al. (2018) consider that “tax incentives for investment are usually poorly designed and ineffective (…) their impact on investment is often negligible and they are likely to trigger costly windfall gains for business” (p. 5). These authors also question the environmental effects of some of the incentives, recommending that governments should not use them.

Castañeda (2018) in analysing the inefficiency and injustice of the Colombian tax system concludes that the political influence of the interest groups of the business community explains the limitations of tax policy in achieving economic growth and redistribution.Footnote 2 Van Kommer (2018) considers that tax incentives are often granted to a specific target group and specific type of income or expense; however, incentives do not come without risks of misuse or abuse. Foreseeable risk may refer to (1) increased number of applicants; (2) under-declaration of income; (3) incorrect declarations; (4) shifting to other categories of income; (5) bringing forward investments or delaying them in order to manipulate the claim of the incentive; (6) transferring income to other entities; and (7) applying the tax incentive to other taxes (p. 279).

Finally, Munongo, Ayo and Robinson (2017), in a study focusing on Southern African countries, point out the disadvantages of incentives as revenue loss, misallocation of resources, enforcement and compliance challenges and corruption due to discretionality in the concession of incentives. To this end, the paper focuses on the economic impact of incentives on tax competition and regional regulatory harmonisation (pp. 159 and 165). In this regard, they state: “It was noted that the use of tax incentives to attract FDI might improve the welfare of individuals in the jurisdiction that applies the incentives, but have external cost implications for residents in other competing jurisdictions that do not adopt tax incentives. Thus, tax incentives were seen to reduce the overall welfare of residents in a region” (p. 165).

Some articles that analyse certain special tax incentives and their impact by sectors are, for example, those by Carpentier and Suret (2016), Poterba (1997), Jorgenson (1996) and Laukkaanen (2018). Despite the disparity in the number of years between these studies, the recommendations they generate for the future evaluation of tax relief policies are important. The Carpetiner and Suret document (2016) analyses how Latin American countries have included tax incentives in their jurisdictions in order to promote “Business Angels” (hereinafter, BAs). The implementation of these policies costs countries millions of dollars, where it is concluded that the economic benefits of these initiatives are obscure and unknown. So much so that programs fail to collect and provide the information needed to conduct comprehensive evaluations of these programs. Thus, the paper, also supported by previous studies, concludes “tax expenditures are generally higher than tax revenues when the additionality and displacement effects of the incentives are considered” (p. 347). However, it recognises that much remains to be analysed, since the vast majority of studies present flaws in their methodological dimension. Thus, for Carpetier and Suret, the following three questions have not been resolved by the literature, and they require measurement: (1)“even if the tax incentive programs attempt to improve investors’ rate of return, little is known about whether this objective has been reached”; (2) “the programs (…) are officially dedicated to BAs, but they are generally open to all taxpayers or qualified investors”; and, finally, (3) “given that the available analyses focus on short-term effects, we know little about the performance, survival and success of firms financed by tax credits” (p. 348).

Poterba (1997) analyses the tax incentives for research and development in the United States, concluding that given their complexity, they give rise to unwanted disincentives. In this regard, he states “Tax incentives and disincentives for investment are often unintentional. The international provision of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code has become so complex that the architects who regularly patch up this structure may fail to perceive the behavioural consequences of new layers of complexity” (p. 72). Jorgenson (1996) demonstrates, through a 5-year analysis, how the new system of regulations for calculating depreciation allowances for tax purposes (the asset depreciation range system, ADR) created in 1971 in the United States generated relatively little impact during the first year and that the maximum impact on investment, gross national product and employment occurred 3 years later. It is interesting to consider that in this case there is economic information that allows us to evaluate the tax measure.

Finally, Laukkaanen (2018), in analysing the “Special Economic Zones” (hereafter SEZs), asserts that if there is an inadequate incentive design, it can result in increased evasion and competitive disadvantages. As such, for Laukkaanen, for example, multinationals can take advantage of these zones to alleviate their overall tax burden through artificial profit shifting from parent company to the entity located in a low tax SEZ, for which the analysis of economic substance is fundamental as is the inclusion in double taxation avoidance conventions of non-discrimination, mutual agreement procedure, most favoured nation clauses, limitation on benefits and principal purpose of the transaction clauses (see also Ferreira and Perdelwitz 2018Footnote 3).

For different doctrinants incentives can take the form of tax holidays, capital investment incentives, reduced corporate tax rates, special economic zones, carryforward loss, investment allowances, accelerated depreciation, initial allowances, investment tax credits, enhanced deductions, reduced tax rates on dividends and interest paid abroad, preferential treatment of long-term capital gains, exemptions (VAT), zero-rating (VAT) and tax havens, among others (Cotrut and Munyandi 2018; James 2016; Tavares-Lehman 2016).

3 International Aspirations for Tax Incentives Based on the OECD’s BEPS Project and the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda

3.1 BEPS Action 5 and What It Means for Tax Incentives

BEPS Action 5 seeks to combat harmful tax practices based on transparency and economic substance. The OECD has detected such practices in two areas: (1) preferential tax regimes, i.e. those that offer advantageous tax conditions for companies that carry out certain activities and therefore provide an incentive to relocate business activities, and (2) agreements with tax administrations or tax rulings and their negative tax effects at global level.

The issue of preferential tax regimes is addressed both in the 1998 report entitled “Harmful tax competition: A global issue” and in Action 5. The latter explores “geographically mobile” activities, for example, financial or service activities, which globalisation and technological advances let move at low cost from one territory to another without requiring a relevant business structure, obtaining tax advantages in the host jurisdictions.

It is important to clarify that a preferential regime is potentially harmful only if it has actually created harmful economic effects according to the OECD guidelines in the BEPS Project on substantial economic activity. Thus, tax bases cannot be artificially shifted from countries where value is created to low-tax countries. In this respect, the tax advantages associated with preferential regimes should only be recognised if the entity that intends to implement them is engaged in a substantial economic activity.Footnote 4

Action 5 of the BEPS Project expands on preferential intellectual property regimes. Thus, countries are free to establish tax incentives that encourage companies to invest in research and development, but these incentives must not generate any distortion or harmful effect on the economy, which is why the requirement for substantial activity is an essential element.

The foregoing shows that the activity performed is of sufficient substance and therefore justifies the application of a preferential tax regime, based on the nexus or relationship between income and expenses related to the development of the intangible asset. In this way, the tax benefits associated with the regime will only be applicable to income obtained from the exploitation of intellectual property on the basis of the proportion between qualified expenses and total expenses. As such, Action 5 expressly establishes a formula for calculating the benefits to be applied by this special tax regime, as well as a breakdown of its variables.Footnote 5

BEPS Action 5 also provides that taxpayers should only be able to apply the tax benefits associated with a preferential regime if they actually substantially pursue the economic activities to which that regime refers. The schemes analysed are those that grant tax benefits to companies engaged, inter alia, in (1) headquarters regimes, (2) distribution regimes, (3) financing or leasing regimes, (4) fund management regimes and (5) banking and insurance regimes.

In conclusion, the OECD does not expect countries to eliminate their preferential regimes but accepts their application only when the entity carries out a substantial activity that justifies it. Despite the above, the role of international bodies such as the OECD and the European Union in establishing international rules and standards has been questioned in the literature. This is how it is for Van Kommer (2018): “The argument put forth by the OECD that the tax policies of preferential regimes not only harm the country whose tax base is being eroded, but those with the preferential regimes as well, has never been sufficiently demonstrated. The assertion that such policy would cause a race to the bottom and those racing will see a corresponding drop in tax revenue together with the bottoming out of tax rates has also been dispelled in the past. As such, the saying of ‘we’re all in this together’ doesn’t really have much weight” (p. 305).

3.2 The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and What It Means for Tax Incentives in Latin America

The 2030 SDGs are aimed, among other things, at reducing (1) low productivity and poor infrastructure, (2) low quality in the provision of education and health services, (3) gender and territorial inequalities in relation to minorities and (4) the accelerated impact of climate change on the poorest segments of society. With an interdisciplinary understanding of sustainable development and in order to achieve the above objectives, the SDA included 17 objectives and 169 goals.

With regard to the fiscal sphere, several studies by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) have analysed tax policies that promote the mobilisation of resources within the framework of these objectives, which include the need to strengthen revenue collection. To this end, it addresses the challenges involved in taxing the digital economy as well as modifying production and consumption patterns in order to encourage the decarbonisation of the economy and achieve improvements in public health (CEPAL 2017, 2019). For the purposes of this document, however, it is very important that for ECLAC the use of fiscal incentives limits the mobilisation of resources, but it recognises that if these incentives are geared towards investment, they can contribute to sustainable and inclusive growth.

Thus, ECLAC analyses that the mobilisation of domestic resources in the region’s countries is limited by the existence of substantial fiscal incentives because the cost of these tax expenditures that operate as transfers of public resources through the tax system is considerable.

Thus, it is fundamental for tax expenditures to be effectively geared towards investment in order to achieve the sustainable development goals. However, for the Commission, the use of these mechanisms should be evaluated through cost-benefit analysis, in order to analyse the interaction between tax policies and public expenditure programs. It is therefore possible to identify whether there are justifications for the establishment or maintenance of these preferential tax treatments or whether it is advisable to replace them with other more efficient and effective measures. This is because not all special tax treatments are effective in encouraging investment; it is the case of low-income countries that resort to costly temporary tax and income tax exemptions to attract investment, when investment tax credits and accelerated depreciation can generate more investment for every dollar spent.

In sum, for ECLAC, the main link between the mobilisation of domestic resources and the SDGs is the tax collection aimed at financing the public expenditure needed to achieve this broad vision of sustainable, inclusive development in harmony with the environment.

In the same line of argument, Zhan and Karl (2016) consider that in order to meet SDGs, tax incentives need to provide low-income countries the resources to improve infrastructure, health service delivery, promotion of renewable energy, research and development (R&D) and education at affordable prices (p. 207). Thus, the authors conclude, from a 2014 survey of investment promotion agencies prepared by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD),Footnote 6 incentive priorities have tended to be economic rather than environmental or social. In this regard, “the above-mentioned UNCTAD IPA survey (2014) revealed that job creation, transfer of technology, and export promotion are the top three policy objectives of existing investment incentives schemes. Thus, these schemes focus primarily on economic goals. Environmental and social SD considerations are not top priorities, although responding agencies confirmed that they have recently gained importance in investment promotion policies. About 40 per cent of IPAs consider SD to have been only somewhat or not at all important five years ago, compared to only 5 per cent today” (p. 207, SD: sustainable development).

4 Current Panorama of Tax Incentives in Latin America, in General, and in the Countries of the Pacific Alliance, in Particular

Since the 1950s, there have been doctrinal references to the tax situation in Latin American countries such as the paper written by Froomkin (1957). The paper analyses the policies adopted in complex sociopolitical environments such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Mexico and concludes that there is an undue transfer of US regulations to these jurisdictions, which established a new approach to depreciation, leading to disparities in marginal income tax rates. The study concludes with a sentence that is shocking: “It may, perhaps, be practical to orient the reform of the tax system towards the punishment of non investors, rather than the reward of investors” (p. 10), which demonstrates the disenchantment with tax incentives.

More recent for Latin America, in general, are the studies by Atria et al. (2018), Podestá and Hanni (2019), Renzio (2019) and CEPAL (2019), the last three discussed at the recent “Regional Seminar on Tax Benefits” event held in Bogotá in September 2019 and organised by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Fescol), Dejusticia and the “International Budget Partnership (IBP)”.Footnote 7 The main conclusions of these studies include the following:

-

1.

Latin American countries have increased their collection from 9.7% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 1960 to 16.2% of the GDP in 2014. The document explains four periods of this growth and its motivations and proposes a new approach to taxation in Latin America based on relational (interaction state-society), historical (influence of history and low collection) and transnational (capital mobility caused also by tax incentives) dimensions (Atria et al. 2018).

-

2.

“The region’s countries need to achieve greater mobilisation of resources to meet the objectives of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. To this end, it is essential that they generate the right conditions and policies to attract foreign direct investment and seek to strengthen tax collection, including the gradual limitation or elimination of those tax expenditures that are not cost-effective” (Podestá and Hanni 2019, p. 5).

-

3.

“In the countries of the Americas, most of the tax incentives for companies are aimed at certain geographical areas (generally remote areas, hostile climates, border areas or regions with less relative development), as well as specific sectors or activities, such as the promotion of renewable energies; research, development and technological innovation projects; certain sectors of industry and agro-industry; tourism; the forestry sector and film projects; among others”. It is concluded, however, that the use of pro-investment incentives such as accelerated depreciation or the application of tax deductions or credits related to the cost of investment is rarely used in the region (Podestá and Hanni 2019, p. 6).

-

4.

Although there is a methodological problem in measuring fiscal expenditure in the region, it could be argued that these fiscal waivers range from 14 to 25% of effective collection. Thus, public expenditure in relation to the tax burden is of 30%. Only 1% of the GDP of Latin American countries is a pro-investment tax expenditure. It is also concluded that tax expenditure on VAT is greater than income and that that of corporate income is greater than that of individuals (Podestá and Hanni 2019, p. 6).

-

5.

For the specific case of the Pacific Alliance countries, not including Colombia,Footnote 8 tax expenditures represent percentages of between 2.1 and 3.1% of the GDP. Mexico has the highest result with 3.1%, of which 1.7% comes from tax expenses associated with income tax and where the benefits received by natural persons are greater than those received by legal persons (0.92% and 0.77%, respectively), while tax expenses associated with VAT represent 1.4% of the GDP. In the case of Chile, its tax expenditures represent 2.9% of the GDP, 2.1% of which are associated with income tax, in equal shares between legal and natural persons; 0.8% of the GDP is associated with tax expenditures associated with VAT. Peru allocates 2.9% of its GDP to tax expenditures, with VAT accounting for the largest portion (1.6%), while expenses related to income tax represent 0.37% of the GDP, 0.2% for natural persons and 0.17% for legal persons. Tax spending on pro-investment incentives is 0.9% of GDP for Peru (44% of total tax spending), 2.4% of GDP for Chile (69% of total tax spending) and 0.9% for Mexico (27% of total tax spending) (Podestá and Hanni 2019).

-

6.

However, as discussed in the theoretical part of this paper, other non-tax factors influence investment decisions in Latin America, such as political stability, security and a stable legal environment (Podestá and Hanni 2019).

-

7.

The majority of Latin American countries present some kind of report on their tax expenditures, but their heterogeneity is very broad, where, for example, Mexico presents an extensive and detailed report in contrast to other countries such as Paraguay. The Mexican report includes policy purposes by incentive as well as evaluations of tax expenditures by income decile, which unfortunately does not coincide with the time when budget debates take place. In the case of Colombia, in the instrument known as the “medium-term fiscal framework”, there is a quantification of tax expenditures only for some national taxes (VAT and income), but not for territorial taxes, but unfortunately this information does not influence budgetary decision-making. In Chile, the budget proposal includes a chapter on tax expenditure that includes projections. Finally, in Peru, a detailed report is published that is linked to the budget proposal (De Renzio 2019, pp. 6–9).

-

8.

Governments in Latin America often include information on estimates of lost revenue but do not publish future revenue projections, effective dates or information on the policy purposes they pursue (De Renzio 2019).

-

9.

Some 3.7% of the GDP in Latin America corresponds to revenues not collected in recent years (2016–2019), i.e. between 10 and 20% of public revenues (De Renzio 2019).

-

10.

An indicator called the “Open Budget Index” produced by the International Budget Partnership shows that governments are much less transparent with respect to tax expenditures than with respect to general budget information, although this situation is not as worrying in Latin America as it is in Western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa (De Renzio 2019, p. 4).

-

11.

In Latin America in general, and in the countries of the Pacific Alliance in particular, there are no details on the process of approval, review and evaluation of tax expenditures. Nor are there accountability mechanisms that would allow for an informed debate on the role of tax expenditures as instruments of fiscal policy (De Renzio 2019, pp. 11 and 18).

-

12.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, of 40 countries analysed, the majority implement tax holidays (29 equivalent to 72%), followed by 26 that use reduced tax rates (65%). 60% use SEZs, 47% investment allowances/tax credits, and 30% R&D deductions (Ogazón and Calderón 2018). For 24 Latin American countries analysed by James (2016), 92% use tax holidays/tax exemption, 50% investment allowance/tax credit, 33% reduced tax rate, 8% R&D tax incentives and 4% super deductions (Table 7.1, 2014). However, the disparity of the percentages of the two previous studies is of concern, although this may be due to the jurisdictions under analysis and to the criteria used to classify tax incentives. Also, as recognised by James (2016, p. 155), there are obstacles to summarising the different types of incentives and the way in which they are administered.

Despite the previous methodological difficulties, and in order to analyse the situation of the tax incentives of the countries of the Pacific Alliance (Mexico, Peru, Chile and Colombia) in terms of income tax (direct taxation) and value-added tax (indirect taxation), I follow the categorisation by James (2016) by which the tax incentives can be classified according to the following typologies: (1) temporary tax exemptions (tax holidays) and a reduction of rates; (2) investment incentives (accelerated depreciation, partial deduction, tax credits and tax deferral); (3) special zones with privileged tax treatment (import duties, income tax benefits, value-added tax benefits); and (4) employment incentives (tax reductions for hiring labour). I also try not only to distinguish tax incentives from direct and indirect taxation but also to tie them to the objectives pursued by the 2030 SDA, taking into account ECLAC studies (CEPAL 2019).

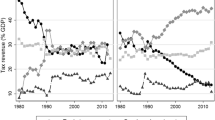

From the following data, referring to income tax incentives (direct taxation), it is concluded that Colombia is the jurisdiction that most offers this type of incentive in relation to the total of the selected sample (14/24, 58%), followed by Chile (13/24, 54%), Mexico (12/24, 50%) and Peru (9/24, 37.5%) (Fig. 6.1).

Number of tax incentives in income tax by Pacific Alliance countries. Source: Authors based on information in Table 6.2

As shown, Peru offers seven of the eight tax incentives in value-added tax analysed (87.5%), Colombia and Mexico, each three (37.5%), and finally Chile with 2 (25%) (Fig. 6.2).

Number of tax incentives in value-added tax by Pacific Alliance countries. Source: Authors based on information from Table 6.3

As analysed, the objectives proposed by the 2030 SDA are aimed at consolidating economic, social and environmental sustainability. As shown in Tables 6.2 and 6.3, it is easy to find a relationship between the purposes of the incentives and the SDGs. For the economic context of the countries of the Pacific Alliance, it is essential to have cost-effective public policies to eradicate extreme poverty and inequalities and achieve an economic scenario that promotes growth, decent work, gender equality and innovation, among other purposes. In this scenario, the role of fiscal policy is essential. Thus, the accountability of the beneficiaries as regards the incentives, in terms of the social investments undertaken, and the quantification of tax expenditure by the State is fundamental, where the amount of the latter cannot be greater than the former. In conclusion, the ideal of an equitable and progressive tax system is that tax incentives, in spite of decreasing collection, significantly increase investments to satisfy social goals.

5 Conclusions and Final Recommendations on Fiscal Public Policy for the Pacific Alliance Countries

Several conclusions can be drawn from the above analysis. First, not all tax benefits are incentives. But for those that are, there is no unanimity in the literature as to their definition; however, they should all meet the following characteristics: they must be special and exceptional tax measures against general rules, favourable to a sector or type of investment to attract it, they seek to increase its rate of return or reduce risks and costs, they must comply with a strict process of qualification of requirements for access, they must ideally be defined for a determined period, they include one or several taxes, they can interact with other pro-investment strategies, and they generate a negative impact on public finances if they are not cost-efficient.

The paper also concludes that, along with tax strategies, there are usually others in favour of investment and that the former are not necessarily effective, although they are the most commonly used in the global context. Faced with their undesired effects, the document analyses different general and special studies by incentives and sectors and relates the tax incentives commonly used in both direct and indirect taxation schemes.

It is also clear that the possible distortions that tax incentives may generate in the existence of preferential regimes is a concern of the OECD’s BEPS Project. It is therefore essential to analyse the substantiality of economic activities, intensifying the BEPS Project into areas such as intellectual property, among others. As for its effectiveness in achieving the SDGs, it is highly pertinent to establish the connection with the pro-investment fiscal policy measures, as well as its constant monitoring and evaluation.

However, the paper explores the discouragement reported regarding tax incentives in the Latin American context by demonstrating the problems related to the quantification of the associated tax expenditure and its cost-efficiency, as well as the poor accountability of the beneficiaries of these incentives. Therefore, in the Pacific Alliance countries, there is no follow-up to such fiscal policies, let alone an adequate relationship with the budgetary processes in place in these countries, thus affecting the SDGs.

In view of the above, and following the recommendations of Redonda et al. (2018), Podestá and Hanni (2019), De Renzio (2019), Van Kommer (2018), CEPAL (2019) and James (2016) in particular, public fiscal policy on tax incentives in Latin American countries in general, and in the Pacific Alliance in particular, should take into account the following:

-

1.

Periodic preparation of reports on tax incentives. Countries should provide constant, timely and detailed reports on the costs, expected benefits, expiration dates, main beneficiaries and goals of the incentives. They should also estimate, as accurately as possible, the tax expenditure that results from them.

-

2.

Linking tax incentive reports to budgetary decision-making. Cost-efficiency analysis of tax incentives should be taken into account when governments prepare their annual budgets, and when they are approved by the corresponding legislature or body at the sub-national level.

-

3.

Constant monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of tax incentives and the participation of multiple actors. Governments, along with citizen oversight and international cooperation, should follow up on fiscal policies that include tax incentives and ensure their cost-effectiveness. They should also review competition and complementarity with pro-investment mechanisms, apart from tax mechanisms.

-

4.

The assessment of tax incentives should include the fulfilment of the international aspirations of the OECD BEPS Project and 2030 SDA. The international standards contained in the BEPS Project and in SDA serve to harmonise tax regimes, avoid harmful tax competition, and make them fairer and more progressive. Some tax incentives can contribute to SDGs beyond the classic social-economic objectives of jobs and growth (e.g. environment, renewable energy, gender equality).

-

5.

Inclusion of tax incentives only in tax rules. It is reiterated practice in Latin American countries that non-tax regulations include tax incentives to promote sectors or activities in particular, in the best of cases, since their introduction is often motivated by particular interests and/or political pressures.

-

6.

Clear criteria in the law for access to tax incentives. In order to avoid corruption in the allocation of incentives, the law must unequivocally establish the requirements for their granting and terms of validity

-

7.

There is a need for coordination between national and subnational governments in the monitoring and evaluation of tax incentives. It is common in the region not to quantify the tax expenditure generated at subnational level by assigned tax incentives, where the discussion usually remains at national level. There is therefore a need for adequate coordination among the different levels of government.

The problem of tax incentives in Latin American is over-diagnosed. Thus, an effort is required from national and subnational governments to improve flat tax structures, with exceptional incentives for investment and periodic evaluations, in order to comply with international standards and achieve more equitable, progressive and efficient tax schemes.

Notes

- 1.

Some of these were also obtained by Ogazón and Calderón (2018, pp. 7 and 8).

- 2.

To analyse the undue pressure of economic sectors for tax benefits, see Valdés (2019).

- 3.

This chapter also delves into how limitation on benefits and principal purpose of the transaction clauses can combat treaty vulnerability to abuse of tax sparing credit clauses (p. 205). In the case of the Double Taxation Avoidance Conventions of the Pacific Alliance countries, most of which include the above clauses following the OECD Model Convention, see the following pages: https://www.mef.gob.pe/es/convenio-para-evitar-la-doble-imposicion, http://www.sii.cl/pagina/jurisprudencia/convenios.htm, https://www.sat.gob.mx/cs/Satellite?blobcol=urldata&blobkey=id&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobwhere=1461173732131&ssbinary=true and https://www.dian.gov.co/normatividad/convenios/Paginas/ConveniosTributariosInternacionales.aspx.

- 4.

This chapter does not explore in depth the relationship between harmful tax competition and tax incentives. It is, however, an important line of research that has been addressed by others (i.e. Littlewood 2004) and will continue to be so for Latin American countries.

- 5.

(Qualified expenses incurred in the development of the intangible asset/Total expenses incurred in the development of the intangible asset) * Total income derived from the intangible asset = Income susceptible of applying the tax benefits associated with the preferential regime.

- 6.

UNCTAD is the main UN body dealing with trade, investment and development issues.

- 7.

Some of the topics discussed in the seminar can be consulted in the article by Medina (2019). The seminar raises the interesting idea of the Centre for Economic and Social Rights, along with other Latin American organizations, to find links between fiscal policy and human rights, a document that will be published in 2020.

- 8.

The only data available for tax expenditures associated with income tax represent 1.3% of GDP, 0.6 for natural persons and 0.70 for legal persons (Podestá and Hanni 2019).

References

Action 5. BEPS project. Retrieved September 26, 2019, from https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/beps-actions/action5/

Atria, J., Groll, C., & Fernanda, V. M. (Eds.). (2018). Rethinking taxation in Latin America: Reform and challenges in times of uncertainty. Latin American political economy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60119-9.

Bolnick, B. (2004). Effectiveness and economic impact of tax incentives in the SADC region. Gaborone: SADC Tax Subcommittee, SADC Trade, Industry, Finance and Investment Directorate.

Carpentier, C., & Suret, J.-M. (2016). The effectiveness of tax incentives for business angels. In Handbook of research on business angels. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8443/10.4337/9781783471720.00021.

Carrizosa, M. (2008). Tax reform: Tax policy, reform, and competitiveness in Latin America. In J. Haar & J. Price (Eds.), Can Latin America compete? New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castañeda, N. (2018). Business groups, tax efficiency, and regressivity in Colombia. In J. Atria, C. Groll, & M. Valdés (Eds.), Rethinking taxation in Latin America. Latin American political economy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2017). Financiamiento de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible en América Latina y el Caribe: desafíos para la movilización de recursos. LC/FDS.1/4. Santiago: CEPAL. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/41169/1/S1700216_es.pdf

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (2019). Panorama fiscal en América Latina. LC/PUB.2019/8-P. Santiago: CEPAL. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44516/1/S1900075_es.pdf

Cotrut, M., & Munyandi, K. (2018). Tax incentives in the BEPS Era (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: IBDF Tax Research Series.

De Renzio, P. (2019). Contabilizados, pero sin rendir cuentas: La transparencia en los gastos tributarios en América Latina. Budget Brief. International Budget Partnership. https://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/tax-expenditure-transparency-in-latin-america-spanish-ibp-2019.pdf

Ferreira, V. A., & Perdelwitz, A. (2018). Chapter 6. Tax incentives and tax treaties. In Tax incentives in the BEPS era (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: IBDF Tax Research Series.

Froomkin, J. (1957). Some problems of tax policy in Latin America. National Tax Journal (Pre-1986), 10(4), 370. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8443/docview/207270416?accountid=34489.

James, S. (2016). Tax incentives around the world. In A. T. Tavares-Lehmann, P. Toledano, L. Johnson, & L. Sachs (Eds.), Rethinking investment incentives: Trends and policy options (pp. 153–176). New York: Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8080/stable/10.7312/tava17298.10.

Jorgenson, D. W. (1996). Investment: Tax policy and the cost of capital. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=48876&lang=es&site=ehost-live.

Klemm, A. (2010). Causes, benefits, and risks of business tax incentives. International Tax and Public Finance, 17(3), 315–336.

Laukkanen, A. (2018). Chapter 5. Special economic zones: The acceptance of tax incentives in the BEPS world. In Tax incentives in the BEPS era (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: IBDF Tax Research Series.

Littlewood, M. (2004). Tax competition: Harmful to whom? Michigan Journal of International Law, 25(1), 411–487.

Medina, M. A. (2019, September). Beneficios tributarios: ¿incentivos o privilegios? El Espectador. https://www.elespectador.com/economia/beneficios-tributarios-incentivos-o-privilegios-articulo-881597

Munongo, S., Akanbi, O. A., Robinson, Z., & College of Economic & Management Sciences, South Africa Department of Economics. (2017). Do tax incentives matter for investment? A literature review. Business and Economic Horizons, 13(2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2017.12.

Ogazón Juárez, L. G., & Calderón Manrique, D.. (2018). Chapter 1. Introduction to tax incentives in the BEPS era. In Tax incentives in the BEPS era (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: IBDF Tax Research Series.

Ogazón Juárez, L. G., & Hamzaoui, R. (2015). Chapter 1. Common strategies against tax avoidance: A global overview. In International tax structures in the BEPS era: An analysis of anti-abuse measures (Vol. 2). Amsterdam: IBFD Tax Research Series.

Podestá, A., & Hanni, M. (2019). Los incentivos fiscales a las empresas en América Latina y el Caribe. Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2019/50). Santiago: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL)/Oxfam Internacional. https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/incentivos_fiscales_web_1.pdf

Poterba, J. M., & National Research Council (U.S.). (1997). Borderline case: International tax policy, corporate research and development, and investment. U.S. Industry, Restructuring And Renewal. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=923&lang=es&site=ehost-live

Redonda, A., Díaz de Sarralde, S., Hallerberg, M., Johnson, L., Melamud, A., Rozemberg, R., Schwab, J., & von Haldenwang, C. (2018). Tax expenditure and the treatment of tax incentives for investment. Economics Discussion Papers No 2018-57. Kiel Institute for the World Economy. http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/journalarticles/2019-12

Ruiz-Vargas, M. A., Velandia-Sánchez, J. M., & Navarro-Morato, O. S. (2017). Incidencia de la política de incentivos tributarios sobre la inversión en el sector minero energético colombiano: un análisis exploratorio de su efectividad. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 17(43), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cc17-43.ipit.

Tavares-Lehmann, A. T. (2016). Types of investment incentives. In A. T. Tavares-Lehmann, P. Toledano, L. Johnson, & L. Sachs (Eds.), Rethinking investment incentives: Trends and policy options (pp. 17–44). New York: Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8080/stable/10.7312/tava17298.5.

UNCTAD. (2000). Tax incentives and foreign direct investment: A Global Survey. ASIT Advisory Studies No. 16.

Valdés, M. F. (2019, July). Beneficios tributarios y la ley de Murphy. El Espectador. https://www.elespectador.com/economia/beneficios-tributarios-y-la-ley-de-murphy-columna-872855

Van Kommer, V. (2018). Chapter 9. The effectiveness of tax incentives. In Tax incentives in the BEPS era (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: IBDF Tax Research Series.

Zee, H., Stosky, J., & Ley, E. (2002). Tax incentives for business investment: A primer for policy makers in developing countries. In World development (Vol. 30, pp. 1497–1516). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Zhan, J., & Karl, J. (2016). Investment incentives for sustainable development. In A. T. Tavares-Lehmann, P. Toledano, L. Johnson, & L. Sachs (Eds.), Rethinking investment incentives: Trends and policy options (pp. 204–227). New York: Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8080/stable/10.7312/tava17298.12.

Zort, E. (2014). Protecting the tax base. Selected topics in protecting the tax base of developing countries. Draft Paper No. 3.

Acknowledgement

I am especially grateful for the investigative support of Alejandra Sarmiento Rojas, graduate assistant of the Master’s in Taxation, and María Camila Londoño Avellaneda, the programme’s academic assistant. Their rigour and dedication have meant that this work is duly supported by extensive literature on global tax incentives that allows a critical perspective of our realities in the Latin American context.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lozano Rodríguez, E. (2021). Tax Incentives in Pacific Alliance Countries, the BEPS Project (Action 5), and the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. In: Mosquera Valderrama, I.J., Lesage, D., Lips, W. (eds) Taxation, International Cooperation and the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. United Nations University Series on Regionalism, vol 19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64857-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64857-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64856-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64857-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)