Abstract

The adsorption of penicillin G (PC-G) from aqueous solution by magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles has been investigated. This experimental study was conducted in a laboratory scale. The effects of various operating parameters such as pH (3–11), the dosage of MgO nanoparticles (0.3–1.5 g/L), contact time (20–150 min), and concentration of PC-G (50–200 mg/L) were studied. The results showed that under optimal conditions of concentration of 50 mg/L, pH 3, MgO nanoparticles dosage of 1.5 g/L and contact time of 60 min, the maximum adsorption capacity (qm) of PC-G adsorption on MgO nanoparticles obtained was 25.66 mg/g. The process of penicillin G adsorption on MgO nanoparticles was found to depend on Langmuir (II) and Langmuir (III) adsorption isotherm models. It could be concluded that the MgO nanoparticles can be used for PC-G removal from its aqueous solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, the presence of pharmaceuticals and related products in the environment is proposed as a noteworthy environmental problem in the world (Richardson et al. 2005; Kord Mostafapour et al. 2017; Ahmadi and kord mostafapour 2017a). Pharmaceuticals have been used as human medicine to treat or prevent microbial infections and eliminate microorganisms, such as bacteria, virus, fungi, and parasites, for about 70 years (Gao et al. 2012; Guler and Sarioglu 2014). The annual application rate of antibiotics has been calculated to be around 100,000–200,000 tons in the world (Gulkowska et al. 2008; Kümmerer 2009).

In addition to the creation of chemical pollution, the antibiotics residue in the environment may cause the production of resistant microorganisms and dispersion of the antibiotic resistance (Aristilde et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2016). The antibiotics along with the sewage, pharmaceutical industries wastewater, veterinary clinics and hospital sewages, and the agricultural products noticeably enter into the water resources and the environment (Carabineiro et al. 2012; Ahmadi et al. 2017a). If the antibiotics are not degraded or eliminated properly during the sewage treatment, in soil or in other environmental compartments, they will reach the surface water, groundwater, and, potentially, drinking water (Carabineiro et al. 2012). The presence of these contaminants in the environment is of great threat to human health (Zhang et al. 2016). Different findings have reported the presence of various kinds of antibiotics in many environmental samples (Batt et al. 2006; Ahmadi et al. 2017b).

Its density in sewage and surface water is 1 μg/L and in hospital sewage more than 150 μg/L (Ahmadi et al. 2017c; Liu et al. 2016). Penicillin G (PC-G) is composed of a core of 6-amino penicillanic acid with a side chain of benzyl. This antibiotic encompasses β-lactam loop which is very sensitive to pH, heat, and β-lactamase enzymes (Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017b; Peterson et al. 2012). Also, it has a biological half-life of 30–60 min (Ahmadi et al. 2017a; Peterson et al. 2012). It is soluble in aqueous solutions, and the mechanism of destruction of bacteria’s cell wall is by stop production peptidoglycan layer (Gad-Allah et al. 2011). Recently, arbitrary and incorrect consumption of antibiotics has become essentially difficult in the field of human health in Iran. Iran has been mentioned as one of the first twenty countries in the consumption of antibiotics and PC-G is the most widely used antibiotics in the country (Brown et al. 2006). Presently, the methods mostly applied to the treatment of antibiotic wastewater are coagulant sedimentation, membrane separation, activated sludge, biological contact oxidation, anaerobic sludge bed, advanced oxidation processes, ozone oxidation, electro-catalytic oxidation, dissolved air flotation and adsorption (Ahmadi et al. 2017c; Sun et al. 2014; Guo and Chen 2015). Many of these methods, such as electrochemical techniques and membrane processes, cannot be used on a large scale due to high costs of operation, repair and maintenance, high electricity consumption, production of toxic by-products, and complex operation. In contrast, adsorption process that is controlled by main physicochemical interactions, such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, polarity, and dipole–dipole interaction, is one of the most cost-effective methods for water treatment (Ren et al. 2011; Rahdar et al. 2019a, b). Particularly, the development of various nano-adsorbents, which offer unique advantages including large specific surface area, selective and abundant adsorption sites, short intraparticle diffusion distance, tunable pore size, and easy regeneration and reusability, has attracted a great deal of attentions (Tajbakhsh et al. 2014; Al-Nour 2009). Among the nanoparticles, magnesium oxide (MgO) is a basic oxide group and it has provided a large range of applications in the process of adsorption (Ghahramani et al. 2016). The most important characteristics of MgO nanoparticles are availability, cheapness, nonvolatility, non-toxicity, stability, reusability, and high absorption capability (Kermani et al. 2013). The main purpose of the research is to study the adsorption of PC-G from aqueous solution using MgO nanoparticles.

Materials and methods

Materials

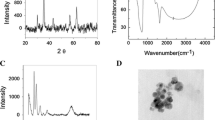

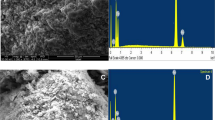

Penicillin G (PC-G) with a molar mass of 372.48 g/mol, molecular formula C16H17KN2O4S, and wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) 248 nm (Ahmadi et al. 2017a) and magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (USA). The chemical structure of PC-G is provided in Fig. 1. The physicochemical properties of MgO nanoparticles are given in Table 1. The structural features of the MgO nanoparticles were determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, JASCO 640) was done on a plus machine (4000–400 cm−1). SEM images were taken with a HITACHI Model S-3000H MgO nanoparticles.

Batch adsorption technique

The effect of MgO nanoparticles (0.3–1.5 g/L), contact time (20–150 min), pH (3–11), and PC-G concentrations (50–200 mg/L) on PC-G removal was investigated. The PC-G solutions with concentrations in the range of 50 to 200 mg/L were prepared by successive dilution of the stock solution with distilled water. To work in a discontinuous system, Erlenmeyer flask was used. At each adsorption test time, the specified volume of PC-G solution with 100 mL of PC-G concentration was added into the Erlenmeyer. The desired conditions were set up, and the 0.5 g/L dose of adsorbent was added to the flask and then mixed in the magnetic stirrer at 180 rpm for 2 h. The pH of the solution was adjusted using 0.1 N HCl or 0.1 N NaOH solutions. The residual concentrations were measured using UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Model: CE-1021). The amount of PC-G adsorbed on MgO nanoparticles, qe, was obtained as follows (Ahmadi et al. 2017b):

Also, the removal efficiency, R (%), was calculated based on the following formula (Ahmadi et al. 2017c; Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017d):

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium liquid-phase concentration of PC-G (mg/L), respectively, Cf is the final concentration, V is the volume of the solution (L), and M is the amount of adsorbent.

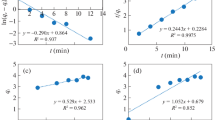

Adsorption isotherms study

The equilibrium adsorption isotherm is important in the design of adsorption systems. Although several isotherm equations are available, four important isotherms including Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were selected (Rahdar et al. 2016; Ahmadi et al. 2017c). The isotherm equations are presented in Table 2.

In order to validate the adsorption isotherm models used in the study, in addition to R2, the parameters of Marquardt’s percent standard deviation (MPSD)and hybrid error function (HYBRID) were also evaluated, which can be described as Eqs. (3) and (4):

The isotherm parameters with the various error functions used in the present study are given in Table 3. In order to determine the goodness of fit of the isotherm models for the adsorption system, it is necessary to analyze the data set using \(\Delta q\) (%) combined with the values of the determined coefficient R2 (Ahmadabadi et al. 2016; Igwegbe et al. 2018; Ahmadi et al. 2018):

where qexp and qcal (mg/g) are the experimental and calculated amount of PC-G adsorbed, respectively, and N is the number of measurements made, respectively.

Results and discussion

FTIR and SEM analysis on MgO nanoparticles

Figure 2a shows the FTIR spectrum (% transmittance vs. wave number) for MgO nanoparticles. The functional groups present in the MgO nanoparticles were identified. Peaks 3419.46 cm−1 (O–H stretch, H-bonded) assigned to alcohols and phenols are very strong. SEM was used to show the surface morphology, size, and location of the individual MgO nanoparticles. The SEM image of MgO nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 2b. The MgO nanoparticles were also found to consist of lamellar- or platelike structures.

Determination of point of zero charge (pHpzc)

To determine the pHzpc, 50 mL nitrite potassium (0.01 M) was added to glass plates and the pH was adjusted in 2–14 using HCl and NaOH. Then, 0.2 g of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO nanoparticles) was added and mixed in a shaker with a velocity of 180 rpm. After 24 h, the final pH was measured. The graph of pHi(initial) against pHf(final) was drawn, and the intersection point was isoelectric pH. The pHzpc for MgO nanoparticles was 12.4 (Rahdar et al. 2018).

The effect of pH

The pH is an important parameter that influences the surface charge of adsorbent, ionization degree of different pollutants, and separation of functional groups on absorbent active sites (Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017c). To obtain the optimal pH value, experiments were carried out by varying initial solution pH from 3 to 11, and under the condition of 50 mg/L of initial penicillin G (PC-G) concentration, 0.5 g/L of MgO nanoparticles dose, and 60 min of contact time. It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the adsorption of PC-G was highly dependent on the pH of the solution, and the maximum amount of removal of the PC-G (qm = 14.75 mg/g, R = 95%) was observed at pH 3. The increase and decrease in PC-G deletion efficiency, in acidic and alkaline pH, depend on pHzpc and pKa parameters. The pKa for PC-G was 2.75, and the pHzpc of MgO nanoparticles of magnesium oxide was 12.4 (Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017c; Bazrafshan et al. 2015). At pH less than pHzpc, the catalyst had a positive charge. In acidic pH, PC-G took carboxyl agent (–COOH), and in pKa less than 2.75, carboxyl group changed to carboxylate charge (Ahmadi and Igwegbe 2018). The increase in yield in acidic pH was resulted from active sites and the load density of protonated adsorbent (carboxyl) that decreased when pH increased. In basic pH, the yield of adsorption decreases because of the high competitivity of OH (Rahdar et al. 2019a).

The effect of adsorbent dosage

The adsorbent dosage is an important parameter to study the removal of PC-G from water by adsorption process, because this parameter determines the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. To evaluate the effect of adsorbent dose on the adsorption of PC-G, 0.3 to 1.5 g/L of MgO nanoparticles was used for adsorption experiments at the fixed conditions of pH 3, 50 mg/L of initial PC-G concentration, and 60 min of contact time. As it can be seen from Fig. 4, the removal efficiency of PC-G increased rapidly with an increase in the adsorbent dosage from 0.3 to 1.5 g/L. A maximum removal of PC-G (qm = 2 mg/g, R = 70%) was achieved at an adsorbent concentration of 1.5 g/L. This is because an increase in the number of available adsorption sites will result in an increase in adsorption capacity (Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017c; Ahmadi et al. 2017b).

The effect of the initial concentration

Figure 5 shows that the effect of PC-G initial concentration (50–200 mg/L) on PC-G removal on MgO nanoparticles at optimum pH of 3 and adsorbent dosage of 1.5 g/L and contact time of 60 min at 298 ± 2 K. As the initial concentration of PC-G was increased from 50 to 200 mg/L, the removal efficiency decreased from 58 to 74.97% (Fig. 5). The effect of PC-G concentration showed that the adsorbent possesses finite adsorption sites, and in less concentrations of PC-G, more adsorbent sites are present. This is the cause for the increase in adsorption of PC-G (Samadi et al. 2013; Rahdar et al. 2017). The reason for the decreasing removal efficiency by enhancement of antibiotic density is the saturation of active places of adsorption (Ahmadi and Kord Mostafapour 2017d; Rahdar et al. 2019b).

The effect of contact time

The effect of contact time on the PC-G adsorption capacity of MgO nanoparticles was investigated at different contact time (20, 40, 60, 80, 120 and 150 min) at PC-G initial concentration of 50 mg/L, pH of 3, and adsorbent dosage of 1.5 g/L at different temperatures (298 and 313 K). Figure 6 shows the effect of contact time on PC-G removal. The efficiency of antibiotic removal was increased by increasing the contact time. The reason for an increase in the removal efficiency at the early hours is that, as time passes, the made cavity and corrosion on the MgO nanoparticles level will be expanded and so increase in the cross section of adsorption (Bazrafshan et al. 2015). The amount of PC-G desorbed is proportional to the amount of PC-G on the adsorbent, which infers dynamic equilibrium (Bazrafshan and Ahmadi 2017; Ahmadi et al. 2017c). The time required to attain this state of equilibrium is referred to as equilibrium time (Bazrafshan and Ahmadi 2017; Rahdar et al. 2017).

Adsorption isotherms

The estimated isotherm parameters, fixed correlation coefficient, R2, and error analysis functions (MPSD, HYBRID, and \(\Delta q\)) for the studied isotherms are presented in Table 3. PC-G adsorption on MgO nanoparticles conformed more to the Langmuir isotherms compared to the Freundlich isotherm with regards to their correlation coefficient, R2 (Table 3). From the equilibrium data of the four Langmuir models, the results showed that the highest adsorptive capacity of PC-G on MgO nanoparticles was 25.66 mg/g based on Langmuir isotherm (III). Considering the error range for each model, it was deduced that Langmuir model (II) and Langmuir model (III) were the most proper models for describing the adsorption process. In fact, the highest amount of R2 and the lowest amounts of MPSD and HYBRID \(\Delta q\) showed better consistency with Langmuir model (II) and Langmuir model (III) (Rahdar and Ahmadi 2017; Watkinson et al. 2007).

Conclusions

The general results of the study showed that MgO nanoparticles could lead to surface adsorption of PC-G from aqueous solutions with a maximum adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of 25.66 mg/g and 80%, respectively, under the optimal adsorption conditions of pH 3, initial concentration of 50 mg/L, and adsorbent dosage of 1.5 g/L. As a result, PC-G adsorption by MgO nanoparticles followed the Langmuir linear models. Among the four linear models, Langmuir (II) model showed the highest correlation coefficient. It was also documented that the Langmuir (II) and Langmuir (III) isotherm models had the best fit with the experimental data.

References

Ahmadabadi M, Rahdar S, Taghavi M (2016) Evaluation of basic red 18 removals from aqueous solution using peanut shell ash. J Health Chem 4:21–31

Ahmadi S, Igwegbe CA (2018) Adsorptive removal of phenol and aniline by modified bentonite: adsorption isotherm and kinetics study. Appl Water Sci 8:170

Ahmadi S, Kord Mostafapour F (2017a) Survey of efficiency of dissolved air flotation in removal penicillin G potassium from aqueous solutions. Br J Pharm Med Res 15:1–11

Ahmadi S, Kord Mostafapour F (2017b) Treatment of textile wastewater using a combined coagulation and DAF processes, Iran, 2016. Arch Hyg Sci 6:229–234

Ahmadi SH, Kord Mostafapour F (2017c) Tea waste as a low cost adsorbent for the removal of COD from landfill leachate: kinetic study. J Sci Eng Res 4:103–108

Ahmadi S, Kord Mostafapour F (2017d) Adsorptive removal of Bisphenol A from aqueous solutions by Pistacia atlantica: isotherm and kinetic studies. Pharm Chem J 4:1–8

Ahmadi S, Banach A, Mostafapour FK, Balarak D (2017a) Study survey of cupric oxide nanoparticles in removal efficiency of ciprofloxacin antibiotic from aqueous solution: adsorption isotherm study. Desalin Water Treat 89:297–303. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2017.21362

Ahmadi S, Kord Mostafapour F, Bazrafshan E (2017b) Removal of aniline from aqueous solutions by coagulation/flocculation–flotation. Chem Sci Int J 1:1–10. https://doi.org/10.9734/CSIJ/2017/32016

Ahmadi Sh, Bazrafshan E, Mostafapour Kord (2017c) Treatment of landfill leachate using a combined coagulation and modify bentonite adsorption processes. J Sci Eng Res 4:58–64

Ahmadi S, Mohammadi L, Igwegbe CA et al (2018) Application of response surface methodology in the degradation of Reactive Blue 19 using H2O2/MgO nanoparticles advanced oxidation process. Int J Ind Chem 9:241–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40090-018-0153-4

Al-Nour GY (2009) Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in the presence of graphite-supported and unsupported ZnO modified with CdS particles. National University, San Diego

Aristilde L, Marichal C, Miehe-Brendle J, Lanson B, Charlet L (2010) Interactions of ox tetracycline with a smectite clay: a spectroscopic study with molecular simulations. Environ Sci Technol 44:7839–7845

Batt AL, Bruce IB, Aga DS (2006) Evaluating the vulnerability of surface waters to antibiotic contamination from varying wastewater treatment plant discharges. Environ Pollut 142:295–302

Bazrafshan E, Ahmadi S (2017) Removal COD of landfill leachate using coagulation and activated tea waste (ZnCl2) adsorption. Int J Innov Sci Eng Technol 4:339–347

Bazrafshan E, Mohammadi L, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Mahvi AH (2015) Heavy metals removal from aqueous environments by electrocoagulation process–a systematic review. J Environ Health Sci Eng 13(1):74

Brown KD, Kulis J, Thomson B, Chapman TH, Mawhinney DB (2006) Occurrence of antibiotics in hospital, residential, and dairy effluent, municipal wastewater, and the Rio Grande in New Mexico. Sci Total Environ 366:772–783

Carabineiro SAC, Thavorn-Amornsri T, Pereira MFR, Serp P, Figueiredo JL (2012) Comparison between activated carbon, carbon xerogel and carbon nanotubes for the adsorption of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. Catal Today 186:29–34

Gad-Allah TA, Ali ME, Badawy MI (2011) Photocatalytic oxidation of ciprofloxacin under simulated sunlight. J Hazard Mater 186:751–755

Gao Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Huang H, Hu J, Shah SM, Su X (2012) Adsorption and removal of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solution by graphene oxide. J Colloid Interface Sci 368:540–546

Ghahramani E, Ghaneian MT, Abouee Mehrizi E, Ghavami ZH, Ahmadi K, Taghavi M, Sadeghi SH (2016) Evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of magnesium oxide nanoparticles in removal of reactive yellow 3 dyestuffs from aqueous. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci 8:117–124

Guler UA, Sarioglu M (2014) Removal of tetracycline from wastewater using pumice stone: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J Environ Health Sci Eng 12:79

Gulkowska A, Leung HW, So MK, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, Yeung LW, Richardson BJ, Lei AP, Giesy JP, Lam PK (2008) Removal of antibiotics from wastewater by sewage treatment facilities in Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China. Water Res 42:395–403

Guo R, Chen J (2015) Application of alga-activated sludge combined system (AASCS) as a novel treatment to remove cephalosporins. Chem Eng J 260:550–556

Igwegbe CA, Banach A, Ahmadi S (2018) Adsorption of reactive blue 19 from aqueous environment on magnesium oxide nanoparticles: kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. Pharm Chem J 5:111–121

Kermani M, Bahrami Asl F, Farzadkia M, Esrafili A, Salahshur Arian S, Arfaeinia H et al (2013) Degradation efficiency and kinetic study of metronidazole by catalytic ozonation process in presence of MgO nanoparticles. Urmia Med J 24:839–850

Kord Mostafapour F, Ahmadi S, Balarak D, Rahdar S (2017) Comparison of dissolved air flotation process Function for aniline and penicillin G removal from aqueous solutions. J Hamadan Univ Med Sci 82:203–209

Kümmerer K (2009) Antibiotics in the aquatic environment: a review—part I. Chemosphere 75:417–434

Liu Z, Zhu M, Wang Z, Wang H, Deng C, Li K (2016) Effective degradation of aqueous tetracycline using a nano-TiO2/carbon electrocatalytic membrane. Materials 9:364

Peterson JW, Petrasky LJ, Seymour MD, Burkhart RS, Schuiling AB (2012) Adsorption and breakdown of penicillin antibiotic in the presence of titanium oxide nanoparticles in water. Chemosphere 87:911–917

Rahdar S, Ahmadi Sh (2017) Removal of phenol and aniline from aqueous solutions by using adsorption on to Pistacia terebinthus: study of adsorption isotherm and kinetics. J Health Res Community Winter 2:35–45

Rahdar S, Khaksefidi R, Alipour V, Saeidi M, Narooie MR, Salimi A, Biglari H, Baneshi MM, Ahamadabadi M (2016) Phenol adsorptive by cumin straw ash from aqueous environments. IIOAB J 7:536–541

Rahdar S, Ahmadi S, Shahraki Zadeh H (2017) Adsorptive removal of aniline from aqueous solutions using Prunus dulcis (Almond): equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. Int J Innov Sci Eng Technol 4:130–135

Rahdar S, Igwegbe CA, Rahdar A, Ahmadi S (2018) Efficiency of sono–nano-catalytic process of magnesium oxide nano particle in removal of penicillin G from aqueous solution. Desalin Water Treat 106:330–335

Rahdar A, Ahmadi S, FuJ RahdarS (2019a) Iron oxide nanoparticle preparation and its use for the removal of fluoride from aqueous solution: application of isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamics. Desalin Water Treat 137:174–182

Rahdar A, Ahmadi S, Fuc J (2019b) Adsorption of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environment by using synthesized nanoceria. Ecol Chem Eng S 26(2):299–311

Ren X, Chen C, Nagatsu M, Wang X (2011) Carbon nanotubes as adsorbents in environmental pollution management: a review. Chem Eng J 170:395–410

Richardson BJ, Lam PK, Martin M (2005) Emerging chemicals of concern: pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in Asia, with particular reference to Southern China. Mar Pollut Bull 50:913–920

Samadi MT, Kashitarash Esfahani Z, Ahangari F, Ahmadi Sh, Jafari J (2013) Nickel removal from aqueous environments using carbon nanotubes. Water Wastewater 24:38–44

Sun P, Pavlostathis SG, Huang CH (2014) Photo degradation of veterinary ionophore antibiotics under UV and solar irradiation. Environ Sci Technol 48:13188–13196

Tajbakhsh M, Farhang M, Hosseini A (2014) MgO nanoparticles as an efficient and reusable catalyst for aza-Michael reaction. J Iran Chem Soc 11:665–672

Watkinson AJ, Murby EJ, Costanzo SD (2007) Removal of antibiotics in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: implications for environmental discharge and wastewater recycling. Water Res 41:4164–4176

Zhang Y, Jiao Z, Hu Y, Lv S, Fan H, Zeng Y, Hu J, Wang M (2016) Removal of tetracycline and oxytetracycline from water by magnetic Fe3O4 graphene. Environ Sci Pollut Res 15:1–9

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful to the laboratory staff of the Department of Environmental Health Engineering, Zabol University of Medical Sciences, for financial support and their collaboration in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahdar, S., Rahdar, A., Khodadadi, M. et al. Error analysis of adsorption isotherm models for penicillin G onto magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Appl Water Sci 9, 190 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1060-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1060-3