Abstract

Purpose

Current labour analgesia practices are evidence-based; however, such evidence often originates in controlled trials, the results of which may not be readily applicable in the context of day-to-day clinical practice. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of and maternal satisfaction with the neuraxial labour analgesia regimen provided at a tertiary care teaching hospital.

Methods

All women with a viable pregnancy who requested neuraxial analgesia for labour during November 2011 at our institution were approached to participate in this prospective study. Patients were managed as per departmental routine based on a patient-controlled epidural analgesia regimen with a maintenance solution of 0.0625% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg·mL−1. Demographic and obstetric data, characteristics of the neuraxial analgesia, pain scores, side effects, and complications were recorded. After delivery, patients completed a satisfaction questionnaire.

Results

All 332 eligible women were approached, and 294 completed the study. Most women received epidural analgesia and considered its placement comfortable. A large number of women reported having experienced pain during the first or second stages of labour (38% and 26%, respectively). Although 24.4% of women required top-ups both by nurses and physicians, adjustment in the local anesthetic maintenance concentration was made in only 7.8% of the cases. Most women (92%) were satisfied with the quality of analgesia. Unintentional dural puncture occurred in three (1%) cases, and there were no cases of intravascular catheter insertion or systemic local anesthetic toxicity. Overweight women (body mass index 25-30 kg·m−2) (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.56; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1 to 5.97), those undergoing induced labour (AOR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.2 to 5.2), and those requiring top-ups by the anesthesiologist (AOR = 5.08; 95% CI: 2.31 to 11.11) were associated with more dissatisfaction with pain control during the first stage of labour.

Conclusion

Although our technique with dilute local anesthetic-opioid infusion was considered effective in previous randomized clinical trials, it did not provide sufficient labour analgesia for a large proportion of women. Nevertheless, most women were satisfied with their pain management and childbirth experience. Strategies to individualize care for labour and delivery should be readily available while providing labour analgesia.

Résumé

Objectif

Les pratiques actuelles en matière d’analgésie pour le travail obstétrical sont fondées sur des données probantes; toutefois, de telles données sont souvent tirées d’études contrôlées, dont les résultats pourraient ne pas être facilement transférables à un contexte de pratique clinique quotidienne. L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer l’efficacité d’un régime d’analgésie neuraxiale pour le travail obstétrical et la satisfaction maternelle concernant ce régime dans un hôpital universitaire de soins tertiaires.

Méthode

En novembre 2011, nous avons demandé à toutes les femmes ayant une grossesse viable et ayant demandé une analgésie neuraxiale pour le travail obstétrical dans notre hôpital si elles acceptaient de participer à cette étude prospective. Les patientes ont été prises en charge selon la routine du département, soit un régime d’analgésie péridurale contrôlée par la patiente avec une solution de maintien à base de bupivacaïne à 0,0625 % et de 2 μg·mL−1 de fentanyl. Les données démographiques et obstétricales, les caractéristiques de l’analgésie neuraxiale, les scores de douleur, les effets secondaires et les complications ont été enregistrés. Après l’accouchement, les patientes ont rempli un questionnaire de satisfaction.

Résultats

Au total, 332 femmes éligibles ont été approchées, et 294 ont complété l’étude. La plupart des femmes ont reçu une analgésie péridurale et jugé son positionnement confortable. Un grand nombre de femmes a rapporté avoir ressenti de la douleur pendant la première ou la deuxième phase du travail obstétrical (38 % et 26 %, respectivement). Bien que 24,4 % des femmes aient demandé un supplément d’analgésie aux infirmières et aux médecins, on n’a ajusté la concentration de maintien de l’anesthésique local que dans 7,8 % des cas. La plupart des femmes (92 %) étaient satisfaites de la qualité de l’analgésie. Il y a eu trois cas de ponction non intentionnelle de la dure-mère (1 %), et aucun cas d’insertion intravasculaire du cathéter ou de toxicité systémique de l’anesthésique local. Les femmes en surcharge pondérale (indice de masse corporelle 25-30 kg·m−2) (rapport de cotes ajusté [RCA] = 2,56; intervalle de confiance [IC] 95 %: 1,1 à 5,97), celles ayant subi une induction (RCA = 2,4; IC 95 %: 1,2 à 5,2), et celles nécessitant un supplément d’analgésie par l’anesthésiologiste (RCA = 5,08; IC 95 %: 2,31 à 11,11) ont été associées à davantage d’insatisfaction quant au contrôle de la douleur pendant la première phase du travail.

Conclusion

Bien que notre technique usuelle, soit une perfusion diluée d’anesthésique local et d’opioïde, ait été considérée comme efficace dans les études cliniques randomisées réalisées par le passé, elle n’a pas fourni suffisamment d’analgésie pour le travail obstétrical à une importante proportion de femmes. Néanmoins, la plupart des femmes étaient satisfaites de la prise en charge de la douleur et de leur accouchement. Les stratégies permettant la personnalisation des soins pour le travail obstétrical et l’accouchement devraient être disponibles facilement pendant la fourniture de l’analgésie pour le travail obstétrical.

Similar content being viewed by others

The current practice of neuraxial labour analgesia in most centres in North America, including our own institution, is evidence based. Most of the evidence that dictates our practice, however, originates in studies produced under very controlled conditions, and it is unknown to what extent the results of these trials are reproducible in the “real world” of clinical practice.1 Furthermore, most of these studies do not evaluate the process of labour and delivery as a whole experience, but rather focus on specific time frames (initiation of analgesia),2 characteristics of analgesia (sensory or motor block),3 mode of delivery,4 or incidence of side-effects and complications.5 In contrast, less evidence is available when it comes to addressing women’s expectations and preferences for analgesia during labour and delivery.6

The available audits in obstetric anesthesia are largely retrospective in nature and are converged on certain aspects of the technique and stages of labour,7 complications,5,8 or mode of delivery.9 In addition to the limitations of being retrospective, most of the audits do not include an objective assessment of patient satisfaction, which is a critical component while assessing the effectiveness of labour analgesia. Prospective observational studies that assess quality and safety of labour analgesia during the entire labour and delivery process and include a special focus on maternal satisfaction are uncommon in the medical literature. Although many studies have used maternal satisfaction as one of their outcomes, they lack in depth and breadth, and the results should be interpreted with caution. A more comprehensive assessment tool that captures the parturients’ point of view is under development and may contribute to a better understanding of women’s needs in the future.5,10

The assessment of the effectiveness of neuraxial analgesia encompassing the entire process of labour and delivery, including maternal satisfaction, may unveil problems, identify opportunities for improvement of clinical practice, and raise new research perspectives. The purpose of this study was to perform a prospective evaluation of the effectiveness of and maternal satisfaction with a patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) regimen using 0.0625% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg·mL−1, initiated either as a combined spinal-epidural (CSE) or as an epidural anesthesia at a tertiary care teaching centre.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB 11-0233-E) and conducted with written informed consent. All women with a viable pregnancy requesting neuraxial analgesia for labour during the month of November 2011 were recruited. When comfortable after the procedure, women were approached for the consent process by the members of the research team not directly involved with their care. Patients presenting for termination of pregnancy or in labour for fetal demise were excluded.

Patients were managed as per departmental routine. A test dose of 2% lidocaine 3 mL followed by a loading dose of 0.125% bupivacaine 10 mL with fentanyl 50 μg was administered. Patient-controlled epidural analgesia was initiated with a maintenance solution of 0.0625% bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 μg·mL−1 with the following settings: bolus 5 mL, continuous infusion 10 mL·hr−1, lockout ten minutes, and a maximum dose of 20 mL every hour. According to patient request, the attending nurse could administer a one-time top-up of 0.125% bupivacaine 10 mL. If ineffective, the anesthesiologist would be called to evaluate the patient, troubleshoot the epidural, and decide whether to give further top-ups, replace the catheter, change the PCEA settings, or increase the concentration of the maintenance solution to 0.125% bupivacaine.

Pain was assessed hourly using a 0-10 verbal numerical pain scale (VNPS), where 0 = no pain and 10 = the most severe pain imaginable. After delivery, before being transferred to the postpartum floor, the patients completed a satisfaction questionnaire composed of ten statements to be classified according to a five-item Likert score (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree). The statements focused on pain experienced during the insertion of epidural and during the first and second stages of labour, side effects, and overall experience with the labour analgesia technique.

Information was collected regarding demographic and obstetric data, characteristics of the neuraxial analgesia, side effects, and complications. All necessary information on the quality of analgesia and complications at all stages of labour and delivery was collected prospectively.

Statistical analysis

No formal sample size calculations were conducted prior to the study, and the study period of one month reflected the available resources.

The study population was summarized using descriptive statistical methods.

We examined the association between failure of analgesia during both first and second stages of labour (dependent variables) and all patient characteristics and variables collected (independent variables). Failure of analgesia or patient dissatisfaction with analgesia was defined as patients having disagreed or strongly disagreed (as per the Likert score) with either of the following two statements: a) I felt NO pain from the time I had my epidural until I started pushing; b) I felt NO pain when I was pushing. For each of the statements above (dependent variables), separately, the group of patients with successful analgesia was compared with the group with failed analgesia regarding all patient characteristics and variables collected using Chi square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables, and Student’s two-sample t test or Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, as appropriate, for continuous variables.

Multivariable logistic regression was employed to determine the association of the independent variables with analgesia failure. Those variables identified as potentially associated with analgesia failure (P < 0.2) in the univariate analysis were included in the models. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) based on the final models derived by a backward selection procedure with a criterion of P < 0.2 was reported. The data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

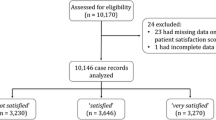

The recruitment process was very successful and allowed a comprehensive prospective evaluation of our practice. During the study period, 508 deliveries occurred, 332 of which were eligible for the study and were approached for enrolment. Ten women refused to participate, 322 were recruited, 28 were lost to follow-up after recruitment, and 294 were included in the data analysis. Most of the losses happened during weekends and night shifts when the labour floor was very busy and a fast patient turnover prevented us from capturing all the study variables. See flowchart in the Figure.

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. The incidence of previous failed epidural was 2.1%, and 3.4% of women had back abnormalities. Most women (93.2%) received epidural analgesia, and the remainder (6.8%) received a combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique. The mean (standard deviation) dilation at epidural insertion was 4.2 (2.0) cm, while the mean time from insertion of epidural to delivery was seven hours (ranging from 23 min to 27 hr). Most procedures were performed by residents. Most anesthesiologists preferred to use a solution of 0.125% bupivacaine as a loading dose. After the epidural placement, about 40% of the women declared having experienced a VNPS higher than 3/10 during the first or second stage of labour. Nearly 50% of the women required epidural top-ups during labour; 25% of them received only one top-up given by the nurse, and the remainder received two or more top-ups given by both nurses and physicians. The nurses’ top-ups were 0.125% bupivacaine 10 mL. The physicians used bupivacaine (66%), lidocaine (21%), and/or fentanyl (13%) in different doses and concentrations in their top-ups. Further details on the anesthetic technique, side effects, and complications are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The incidence of hypotension was 9.1%, and the incidence of pruritus, fetal bradycardia, and nausea or vomiting was 7.1% each. As for the technical complications, three (1%) dural punctures occurred, and the epidural catheter had to be replaced in 13 (4.4%) women. There was no detected case of intravascular injection of local anesthetic or seizure.

Sixty-three percent of women presented in spontaneous labour, and 52% of those required oxytocin augmentation. Thirty-seven percent were scheduled for induced labour. Malpresentation, defined as any presentation other than the occipitoanterior position, was detected in 6.5% of the parturients. The delivery mode was spontaneous vaginal in 72% of patients and assisted vaginal in 13%, either by vacuum extraction (10.5%) or forceps (2.5%). Forty-six (16%) women underwent Cesarean delivery, and 95.6% of the epidurals in situ worked well for the procedure; two (0.6%) women had their epidural converted to general anesthesia. The main indications for Cesarean delivery were atypical/abnormal fetal heart rate in 37%, arrest of dilation or descent in 58%, maternal fever in one woman, and severe vaginismus in another. The type of labour, mode of delivery, and the incidence of malpresentation are presented in Table 4.

According to the responses to the satisfaction questionnaire, most women (90%) considered the placement of the epidural comfortable. One hundred and thirty-four (45%) women reported experiencing pain during the first or second stages, although most of them considered that the epidural worked well (85%). The detailed responses to the satisfaction questionnaire are shown in Table 5.

The results of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses related to analgesia failure during the first stage of labour are reported in Tables 6 and 7. The following variables were associated with anesthesia failure: patients’ overweight status (body mass index 25-30) (AOR = 2.56; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1 to 5.97), need for top-ups given by the anesthesiologist (AOR = 5.08; 95% CI: 2.31 to 11.11), and induced labour (AOR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.2 to 5.2). Nausea or vomiting was associated with lower odds of analgesia failure (AOR = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.94).

The results of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses related to analgesia failure during the second stage of labour did not show any statistically significant associations.

Discussion

Overall, the epidural or CSE analgesia regimen offered at our institution led to a very low number of complications; however, we encountered a high incidence of women reporting pain (VNPS > 3) during the first or second stages of labour. Overweight women and those undergoing induction of labour were most likely to disagree with the statement that they felt no pain during the first stage of labour. Although a large proportion of patients requested multiple top-ups by nurses and physicians, the change to a stronger local anesthetic maintenance solution, readily available on the floor, occurred in just a few cases. Interestingly, however, most patients were satisfied with their pain management.

In order to capture the parturients’ point of view on the whole labour experience, our questionnaire focused on pain during the first and second stages separately, side effects, and overall experience. Patients completed the questionnaire within two hours of delivery before being transferred to the postpartum unit. Most patients reported being comfortable during placement of the epidural, but almost 40% of them disagreed with the statement “I felt NO pain from the time I had my epidural until I started pushing”. Similarly, 25% disagreed with the statement referring to lack of pain during the second stage. This information obtained from the questionnaire is in keeping with the pain scores collected during labour. Our findings are not consistent with those of other studies using dilute solutions of bupivacaine11-13 and probably imply that the environment of randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) may not completely replicate “real life” practice.1 When drugs or techniques proved useful in RCTs are incorporated into clinical practice, the results may be different.14 Carvalho et al. 11 compared different patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) regimens of bupivacaine for labour analgesia. In one of the study groups using nearly the same management protocol as ours (i.e., a continuous infusion of 0.0625% bupivacaine 10 mL·hr−1 with sufentanil 0.35 μg·mL−1, a bolus of 6 mL and a lock-out interval of eight minutes), 24% of women required rescue boluses, which is nearly half of that found in our study. Different explanations may be offered to justify the higher incidence of insufficient analgesia in our study: the smaller volume used in the loading dose (10 mL vs 15-20 mL), the different expectations regarding analgesia in the studied samples, or simply the inability to reproduce RCT findings in daily clinical practice. Two similar studies15,16 comparing continuous infusions of 0.125% and 0.0625% bupivacaine without a PCEA bolus also found that 40-60% of patients required supplemental doses when receiving the low concentration solution. In those cases, the lack of PCEA boluses could justify the findings.

Results from dose-finding studies have found that 0.048% is the minimum local anesthetic concentration (MLAC-EC50 [effective concentration in 50% of women]) of bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 μg·mL−1 in labour.17 Using the table of normal deviates, the effective concentration in 95% of patients (EC95) could be estimated to be 0.091%.18,19 Therefore, 0.0625% bupivacaine may not be sufficient to provide consistent analgesia to every woman, but rather to approximately 60% of them. This is important information, and perhaps our clinical practice, as reflected by the results of this study, proves this point. It should be highlighted, however, that MLAC studies are designed to obtain EC50, and EC95 is assumed from mathematical treatment; therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting EC95 values. Furthermore, most MLAC studies express the concentration of local anesthetic required to initiate an epidural labour analgesia regimen. To date, one study by Ginosar et al.20 would be more applicable to the discussion of our results. In their study, the authors looked at the MLAC of bupivacaine required during maintenance of epidural analgesia, and in the context of the epidural infusion of fentanyl at 30 μg·hr−1, they determined the MLAC to be only 0.019% (95% CI 0.000 to 0.038). Nevertheless, these results are of limited value to suggest a useful concentration for clinical use, as they express EC50, not EC95.

A large retrospective study12 evaluating the need for anesthetic interventions in women who received bupivacaine in three different concentrations (0.04%, 0.0625%, and 0.125%) reported that the number of interventions was similar regardless of the concentration of local anesthetic used. While patients receiving lower concentrations required more supplemental analgesic doses, those receiving higher concentrations required more treatment for hypotension. Therefore, simply increasing the concentration of the maintenance solution for all women in our practice may not be the best solution, especially given that our PCEA regimen was satisfactory to most patients. Our results may suggest, however, that more education aimed at the individualization of PCEA regimens is needed for patients, nurses, and physicians. Despite the fact that almost 40% of women experienced pain during the first stage of labour and 24% required multiple supplemental top-ups, our study shows that the change to a maintenance solution of higher concentration occurred in only 7.8% of the cases.

Our multivariable regression model revealed that women who were most likely to disagree with the statement that they had no pain during the first stage of labour were those who were overweight and those undergoing induced labour. These results are in keeping with a previous survey reporting more pain in primiparous women and in those having induced or augmented labour.21 These results are also in keeping with those of Capogna et al.22 who showed greater analgesic requirement in prostaglandin-induced labour when compared with spontaneous labour. Furthermore, women who requested a top-up by the anesthesiologist in addition to that given by the nurse were more likely to disagree that they had no pain. Some of these women went on to request multiple top-ups, indicating insufficient local anesthetic concentration in the maintenance solution, but in the majority of cases, that did not prompt the change to a higher concentration. Our results suggest that a change in the maintenance solution should be contemplated once a top-up by the anesthesiologist is required.

Interestingly, despite the high incidence of insufficient analgesia, there was high overall satisfaction with the pain management. Satisfaction is a very complex concept and knowingly very difficult to assess. The first problem in measuring satisfaction is to understand how it is defined. So far, there is a lack of validated satisfaction questionnaires published for use in women during labour. In 1987, Lomas et al. made one of the first attempts to create a labour and delivery satisfaction index.23 Unfortunately, their instrument cannot be used to assess women’s views on specific aspects of intrapartum care. Further attempts to assess satisfaction were comprehensively reviewed by Hodnett.24 She identified four factors that appear to be paramount to maternal satisfaction: personal expectations, the amount of support from caregivers, the quality of the caregiver-patient relationship, and the involvement of the women in the decision-making. She further suggests that pain relief and medical interventions do not have a direct influence on satisfaction. This is in accordance with our results. Despite the incidence of 40% of pain during first stage, more than 90% of women reported overall satisfaction. Efforts continue to build a solid questionnaire to assess satisfaction during labour, and a quality index is being developed that would reflect the parturient’s point of view.10

The main limitation of our study is the short period of data collection; however, we had only the resources required to run this prospective project 24 hr per day for one month. Furthermore, as a single centre study recruiting patients over one month, the external validity of our findings may be limited. Women’s expectations toward labour analgesia may be influenced by many factors, including the information that is given to them during prenatal care and the interaction with health care professionals other than the anesthesiologist during labour and delivery. At our institution, the Department of Anesthesia provides bimonthly complimentary educational sessions on labour analgesia to all women; however, only a fraction of them will attend these sessions, and many will have obtained information from different sources.

We conclude that our neuraxial labour analgesia practice of PCEA with a dilute solution of 0.0625% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg·mL−1 is effective for most women delivering at our institution and is associated with high patient satisfaction. Notwithstanding, some women will require multiple top-ups and a higher concentration of local anesthetic, and strategies to respond quickly to individualized needs should be readily available. Most importantly, anesthesiologists and nurses/midwives involved in their care should be educated on how to respond to such needs in the most appropriate way. Prospectively designed studies of labour analgesia such as this may offer a unique opportunity for testing the effectiveness and safety of evidence-based practice in routine clinical care. Prospective evaluation of our daily practice is challenging and requires considerable resources; however, these studies allow an objective documentation of women’s experience of pain during labour epidural analgesia, highlighting areas of deficiencies in clinical care and offering a unique opportunity to improve practice.

References

Vohra S, Shamseer L, Sampson M. Efficacy research and unanswered clinical questions. JAMA 2011; 306: 709.

Lilker S, Rofaeel A, Balki M, Carvalho JC. Comparison of fentanyl and sufentanil as adjuncts to bupivacaine for labor epidural analgesia. J Clin Anesth 2009; 21: 108-12.

de la Chapelle A, Carles A, Gleize V, et al. Impact of walking epidural analgesia on obstetric outcome of nulliparous women in spontaneous labour. Int J Obstet Anesth 2006; 15: 104-8.

Reynolds F, Russell R, Porter J, Smeeton N. Does the use of low dose bupivacaine/opioid epidural infusion increase the normal delivery rate? Int J Obstet Anesth 2003; 12: 156-63.

Pan PH, Bogard TD, Owen MD. Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004; 13: 227-33.

Mhyre JM. Assessing quality with qualitative research. Can J Anesth 2010; 57: 402-7.

Carvalho B, Coleman L, Saxena A, Fuller AJ, Riley ET. Analgesic requirements and postoperative recovery after scheduled compared to unplanned cesarean delivery: a retrospective chart review. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010; 19: 10-5.

Singh S, Chaudry SY, Phelps AL, Vallejo MC. A 5-year audit of accidental dural punctures, postdural puncture headaches, and failed regional anesthetics at a tertiary-care medical center. ScientificWorldJournal 2009; 9: 715-22.

Dresner M, Brocklesby J, Bamber J. Audit of the influence of body mass index on the performance of epidural analgesia in labour and the subsequent mode of delivery. BJOG 2006; 113: 1178-81.

Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C, et al. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anesth 2010; 57: 468-78.

Carvalho B, Cohen SE, Giarrusso K, Durbin M, Riley ET, Lipman S. “Ultra-light” patient-controlled epidural analgesia during labor: effects of varying regimens on analgesia and physician workload. Int J Obstet Anesth 2005; 14: 223-9.

Hess PE, Pratt SD, Oriol NE. An analysis of the need for anesthetic interventions with differing concentrations of labor epidural bupivacaine: an observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth 2006; 15: 195-200.

Ginosar Y, Davidson EM, Firman N, Meroz Y, Lemmens H, Weiniger CF. A randomized controlled trial using patient-controlled epidural analgesia with 0.25% versus 0.0625% bupivacaine in nulliparous labor: effect on analgesia requirement and maternal satisfaction. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010; 19: 171-8.

Djulbegovic B, Paul A. From efficacy to effectiveness in the face of uncertainty indication creep and prevention creep. JAMA 2011; 305: 2005-6.

Chestnut DH, Owen CL, Bates JN, Ostman LG, Choi WW, Geiger MW. Continuous infusion epidural analgesia during labor: a randomized, double-blind comparison of 0.0625% bupivacaine/0.0002% fentanyl versus 0.125% bupivacaine. Anesthesiology 1988; 68: 754-9.

Russell R, Quinlan J, Reynolds F. Motor block during epidural infusions for nulliparous women in labour: a randomized double-blind study of plain bupivacaine and low dose bupivacaine with fentanyl. Int J Obstet Anesth 1995; 4: 82-8.

Lyons G, Columb M, Hawthorne L, Dresner M. Extradural pain relief in labour: bupivacaine sparing by extradural fentanyl is dose dependent. Br J Anaesth 1997; 78: 493-7.

Columb MO, Lyons G. Determination of the minimum local analgesic concentrations of epidural bupivacaine and lidocaine in labor. Anesth Analg 1995; 81: 833-7.

Patel NP, Armstrong SL, Fernando R, et al. Combined spinal epidural vs epidural labour analgesia: does initial intrathecal analgesia reduce the subsequent minimum local analgesic concentration of epidural bupivacaine? Anaesthesia 2012; 67: 584-93.

Ginosar Y, Columb MO, Cohen S, et al. The site of action of epidural fentanyl infusions in the presence of local anesthetics: a minimum local analgesic concentration infusion study in nulliparous labor. Anesth Analg 2003; 97: 1439-45.

Paech MJ. The King Edward Memorial Hospital 1,000 mother survey of methods of pain relief in labour. Anaesth Intensive Care 1991; 19: 393-9.

Capogna G, Parpaglioni R, Lyons G, Columb M, Celleno D. Minimum analgesic dose of epidural sufentanil for first-stage labor analgesia: a comparison between spontaneous and prostaglandin-induced labors in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology 2001; 94: 740-4.

Lomas J, Dore S, Enkin M, Mitchell A. The labor and delivery satisfaction index: the development and evaluation of a soft outcome measure. Birth 1987; 14: 125-9.

Hodnett ED. Pain and women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 186: S160-72.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following contributions: Kristi Downey MSc, Perinatal Research Coordinator at the Department of Anesthesia and Pain Management, Mount Sinai, for her invaluable help and support in all stages of this study and manuscript production; Labour and Delivery Unit nurses and midwives at Mount Sinai Hospital for facilitating the contact with patients and data collection; Xiang Y Ye MSc, Maternal-Infant Care Research Centre, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada for the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author contributions

Jefferson Clivatti, Naveed Siddiqui, and Jose C.A. Carvalho planned the study, reviewed the literature, and wrote the manuscript. Jefferson Clivatti, Naveed Siddiqui, Akash Goel, Melissa Shaw, Ioana Crisan, and Jose C.A. Carvalho conducted the study. Jose C.A. Carvalho submitted the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clivatti, J., Siddiqui, N., Goel, A. et al. Quality of labour neuraxial analgesia and maternal satisfaction at a tertiary care teaching hospital: a prospective observational study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 60, 787–795 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-9976-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-9976-9