Abstract

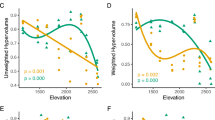

Earlier observations that plant clonality, i.e., production of potentially independent offspring by vegetative growth, increase in importance in cold climates such as in arctic and alpine regions, have been recently questioned. However, lack of data obtained using a comparable methodology throughout different regions limit such comparisons. Here we present a classification of clonal growth forms for vascular plants from East Ladakh (an arid mountain range in NW Himalaya, India), and assess the relationship of these forms with multiple environmental gradients. Based on field assessment of clonality in 540 species we distinguished 20 growth forms, which were then grouped into four broader space occupancy strategies. Occurrence in communities and relationship with environmental characteristics and altitude were analyzed using multivariate methods. The most abundant growth form was represented by non-clonal perennial species with a pleiocorm having short branches, prevailing in steppes, Caragana shrubs and screes. The most abundant clonal species were those with very short epigeogenous rhizomes, such as turf graminoids prevailing in wet Kobresia grasslands. Two principal environmental gradients, together with several abiotic variables, affected space occupancy strategies: moisture and altitude. Non-spreading integrators prevailed on shaded rocky slopes, non-spreading splitters in wet grasslands and spreading splitters at the wettest sites. Spreading integrators were the least frequent strategy predominantly occurring at the most elevated sites. Because relevance of clonality decreased with altitude and different communities host different sets of clonal growth strategies, comparison with other cold climate regions should take multiple environmental gradients into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baitulin IO (1979) Kornevaia sistema rastenii aridnoi zony Kazakhstana (Root systems of plants of the arid zone in Kazakhstan). Nauka, Alma-Ata

Barkman JJ (1988) New systems of plant growth forms and phenological plant types. In Werger MJA, van der Aart PJM, During HJ, Verhoeven JTA (eds) Plant form and vegetation structure. SPB Academic Publishing, The Hague, pp 9–44

Bhattacharyya A (1989) Vegetation and climate during the last 30000 years in Ladakh. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 73:25–38

Billings WD (1974) Adaptations and origins of alpine plants. Arctic Alpine Res 6:129–142

Bliss LC (1971) Arctic and alpine life cycles. Annual Rev Ecol Syst 2:405–438

Callaghan TV, Carlsson BA, Jónsdóttir IS, Svenson BM, Jonasson S (1992) Clonal plants and environmental change – Introduction to the proceedings and summary. Oikos 63: 341–347

Callaghan TV, Jonasson S, Brooker RW (1997) Arctic clonal plants and global change. In de Kroon H, van Groenendael JM (eds) The ecology and evolution of clonal plants. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, pp 381–403

Chowdhery HJ, Rao RR (1990) Plant life in the Himalayan cold deserts: some adaptive strategies. Bull Bot Surv India 32:43–56

de Kroon H, van Groenendael J (1997) The ecology and evolution of clonal plants. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden

den Hartog C, Segal S (1964) A new classification of water-plant communities. Acta Bot Neerl 13:367–393

Dickoré WB, Miehe G (2002) Cold spots in the highest mountains of the world – diversity patterns and gradients in the flora of the Karakorum. In Körner C, Spehn E (eds) Mountain biodiversity: a global assessment. Parthenon Publishers, Lancaster, pp 129–147

Drude O (1887) Deutschlands Pflanzengeographie. Handb Deutsch Landes- Volksk 4:1–502

Du Rietz GE (1931) Life-forms of terrestrial flowering plants. Acta Phytogeogr Suec 3:1–95

Dvorský M, Doležal J, de Bello F, Klimešová J, Klimeš L (2011) Vegetation types of East Ladakh: species and growth form composition along main environmental gradients. Appl Veg Sci (in press)

Evette A, Bédécarrats A, Bornette G (2009) Environmental constraints influence clonal traits of herbaceous plant communities in an Alpine Massif. Folia Geobot 44:95–108

Gimingham CH (1951) The use of life form and growth form in the analysis of community structure, as illustrated by a comparison of two dune communities. J Ecol 39:396–406

Grace JB (1993) The adaptive significance of clonal reproduction in angiosperms – an aquatic perspective. Aquatic Bot 44:159–180

Grime JP (2006) Trait convergence and trait divergence in herbaceous plant communities: mechanisms and consequences. J Veg Sci 17:255–260

Grime JP, Hodgson JG, Hunt R (1988) Comparative plant ecology. Unwin-Hyman, London

Grisebach A (1872) Die Vegetation der Erde nach ihrer klimatischen Anordnung I, II. W. Engelmann, Leipzig

Halassy M, Campetella G, Canullo R, Mucina R. (2005) Patterns of functional clonal traits and clonal growth modes in contrasting grasslands in the central Apennines, Italy. J Veg Sci 16:29–36

Hallé F, Oldeman RAA, Tomlinson PB (1978) Tropical trees and forests. An architectural analysis. Springer Verlag, New York

Halloy S (1990) A morphological classification of plants, with special reference to the New Zealand alpine flora. J Veg Sci 1:291–304

Hartmann H (1957) Studien über die vegetative Fortpflanzung in den Hochalpen. Bischofberger & Co., Buchdruckerei Untertor, Chur

Hartmann H (1983) Pflanzengesellschaften entlang der Kashmirroute in Ladakh. Jahrb Ver Schutz Bergwelt 48:131–173

Hartmann H (1984) Neue und wenig bekannte Blütenpflanzen aus Ladakh mit einem Nachtrag zur Flora des Karakorum. Candollea 39:507–537

Hartmann H (1987) Pflanzengesellschaften trockener Standorte aus der subalpinen und alpinen Stufe im südlichen und östlichen Ladakh. Candollea 42:277–326

Hartmann H (1990) Pflanzengesellschaften aus der alpinen Stufe des westlichen, südlichen und östlichen Ladakh mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der rasenbildenden Gesellschaften. Candollea 45:525–574

Hartmann H (1995) Beitrag zur Kenntnis der subalpinen Wüsten-Vegetation im Einzugsgebiet des Indus von Ladakh (Indien). Candollea 50:367–410

Hartmann H (1997) Zur Flora und Vegetation der Halbwüsten, Steppen und Rasengesellschaften im südöstlichen Ladakh (Indien). Jahrb Ver Schutz Bergwelt 62:129–188

Hartmann H (1999) Studien zur Flora und Vegetation im östlichen Transhimalaya von Ladakh (Indien). Candollea 45:171–230

Hejný S (1960) Ökologische Charakteristik der Wasser- und Sumpfpflanzen in der slowakischen Tiefebenen (Donau und Theissgebiet). Vydavateľstvo SAV, Bratislava

Hess E (1909) Über die Wuchsformen der alpinen Geröllpflanzen. Arbeit aus dem Botanischen Museum des eidg. Polytechnikum Zürich, Druck von C. Heinrich, Dresden

Hill MO, Šmilauer P (2005) TWINSPAN for Windows version 2.3. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Huntingdon and University of South Bohemia, České Budějovice

Holzner W, Kriechbaum M (1998) Man’s impact on the vegetation and landscape in the Inner Himalaya and Tibet. In Elvin M, Ts’ui-Jung L (eds) Sediments of time. Environment and society in Chinese history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 53–106

Jina PS (1995) High pasturelands of Ladakh Himalaya. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi

Jonasson S, Callaghan TV (1992) Root mechanical properties related to disturbed and stressed habitats in the Arctic. New Phytol 122:179–186

Jónsdóttir IS, Watson M (1997) Extensive physiological integration: an adaptive trait in resource-poor environments? In de Kroon H, van Groenendael J (eds) The ecology and evolution of clonal plants. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, pp 109–136

Jónsdóttir IS, Callaghan TV, Headley AD (1996) Resource dynamics within arctic clonal plants. Ecol Bull 45:53–64

Kala CP, Mathur VB (2002) Patterns of plant species distribution in the Trans-Himalayan region of Ladakh, India. J Veg Sci 13:751–754

Kästner A, Karrer G (1995) Übersicht der Wuchsformtypen als Grundlage für deren Erfassung in der “Flora von Österreich”. Fl Austr Novit 3:1–51

Klimeš L (2003) Life-forms and clonality of vascular plants along an altitudinal gradient in E Ladakh (NW Himalayas). Basic Appl Ecol 4:317–328

Klimeš L (2008) Clonal splitters and integrators in harsh environments of the Trans-Himalaya. Evol Ecol 22:351–367

Klimeš L, Dickoré WB (2006) Flora of Ladakh (Jammu & Kashmir, India). A preliminary checklist. Available at: http://www.butbn.cas.cz/klimes

Klimeš L, Doležal J (2010) An experimental assessment of the upper elevational limit of flowering plants in the Western Himalayas. Ecography 32 (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.05967.x)

Klimeš L, Klimešová J (1999) CLO-PLA2 – A database of clonal plants in central Europe. Pl Ecol 141:9–19

Klimeš L, Klimešová J (2000) Plant rarity and the type of clonal growth. Z Ökol Naturschutz 9:43–52

Klimeš L, Klimešová J (2005) Clonal traits. In Knevel IC, Bekker RM, Kunzmann D, Stadler M, Thompson K (eds) The Leda traitbase collecting and measuring standards of life-history traits of the Northwest European flora. EDA Traitbase project, University of Groningen, Community and Conservation Ecology Group, Groningen, pp 66–88

Klimeš L, Klimešová J, Hendriks R, van Groenendael J (1997) Clonal plant architectures: a comparative analysis of form and function. In de Kroon H, van Groenendael J (eds) The ecology and evolution of clonal plants. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, pp 1–29

Klimešová J, de Bello F (2009) CLO-PLA: the database of clonal and bud bank traits of Central European flora. J Veg Sci 20:511–516

Klimešová J, Klimeš L (2008) Clonal growth diversity and bud banks in the Czech flora: an evaluation using the CLO-PLA3 database. Preslia 80:255–275

Körner Ch (1999a) Alpine plant life. Springer Verlag, Berlin

Körner Ch (1999b) Alpine plants: stressed or adapted? In Press MC, Scholes JD, Barker MG (eds) Physiological plant ecology. Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp 297–311

Krumbiegel A (1998) Growth forms of annual vascular plants in central Europe. Nordic J Bot 18:563–575

Krumbiegel A (1999) Growth forms of biennial and pluriennial vascular plants in central Europe. Nordic J Bot 19:217–226

Lepš J, Šmilauer P. (2003) Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lovett Doust L (1981) Population dynamics and local specialization in a clonal perennial (Ranunculus repens). 1. The dynamics of ramets in contrasting habitats. J Ecol 69:743–755

Lukasiewicz A (1962) Morfologiczno-pozvojove typy bylin (Morphologic development types of perennials). Poznaňskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciól Nauk, Wydz Mat-Przyr, Prace Komis Biol 27(1):1–398

Miehe G, Winiger M, Böhner J, Zhang YL (2001) The climatic diagram map of High Asia. Purpose and concepts. Erdkunde 55:94–97

Pakeman RJ, Quested HM (2007) Sampling plant functional traits: what proportion of the species need to be measured? Appl Veg Sci 10:91–96

Pakeman RJ, Garnier E, Lavorel S, Ansquer P, Castro H, Cruz P, Doležal J, Eriksson O, Freitas H, Golodets C, Kigel J, Kleyer M, Lepš J, Meier T, Papadimitriou M, Papanastasis VP., Quested H, Quétier F, Rusch G, Sternberg M, Theau J-P, Thébault A, Vile D (2008) Impact of abundance weighting on the response of seed traits to climate and land use. J Ecol 96:355–366

Parsons DJ (1976) Vegetation structure in the mediterranean scrub community of California and Chile. J Ecol 64:435–447

Rauh W (1939) Über polsterförmigen Wuchs. Nova Acta Leopold 7/49:267–508

Rauh W (1987) Tropische Hochgebirgpflanzen. Sitzungsber Heidelberger Akad Wiss Math-Natuwiss Kl 3:105–304

Raunkiaer C (1907) Planterigets Livsformer og deres Betydning for Geografien. Munskgaard, Copenhagen

Raunkiaer C (1910) Statistik der Lebensformen als Grundlage für die biologische Pflanzengeographie. Beih Bot Centralbl 27:171–206

Rawat GS, Adhikari BS (2005) Floristics and distribution of plant communities across moisture and topographic gradients in Tso Kar basin, Changthang plateau, eastern Ladakh. Arctic Antarct Alpine Res 37:539–544

Serebrjakov IG (1964) Zhiznennyje formy vysshikh rastenii ikh izuchenie (Life-forms of higher plants and their study). In Lavrenko EM, Korchagin AA (eds) Field geobotany. Nauka, Moskva, pp 146–205

Sosnová M, van Diggelen R, Klimešová J (2010) Which clonal growth organs are found in various wetland communities? Aquatic Bot (in press)

Stewart RR (1916–1917) The flora of Ladakh. Bull Torrey Bot Club 43:571–588 and 625–650

Stöcklin J, Bäumler E (1996) Seed rain, seedling establishment and clonal growth strategies on a glacier foreland. J Veg Sci 7:45–56

Tamm A, Kull K, Sammul M (2002) Classifying clonal growth forms based on vegetative mobility and ramet longevity: a whole community analysis. Evol Ecol 15:383–401

ter Braak CJF, Šmilauer P (1998) CANOCO reference manual and user’s guide to Canoco for Windows. Software for canonical community ordination (version 4). Centre for Biometry, Wageningen

van Groenendael JM, de Kroon H (1990) Clonal growth in plants: regulation and function. SPB Academic Publishing, The Hague

van Groenendael JM, Klimeš L, Klimešová J, Hendriks RJJ (1996) Comparative ecology of clonal plants. Philos Trans, Ser B 351:1331–1339

von Humboldt A (1806) Ideen zu einer Phisiognomik der Gewächse. Cotta, Stuttgart

von Lampe M (1999) Vorschlag zur Bezeichnung der Innovations- und Überdauerungsorgane bei den terrestrischen Stauden Zentraleuropas. Beitr Biol Pflanzen 71:335–367

Warming E (1923) Ökologiens Grundformer. Kongel Danske Vidensk Selsk Skr, Naturvidensk Math Afd 8(4):120–187

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jan W. Jongepier for linguistic improvements and Bernhardt W. Dickoré and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The study was supported by the Institute of Botany Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (AV0Z60050516), grant GAAV IAA600050802 and the CNRS PICs 4876 project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Identification key of clonal growth forms of vascular plants in eastern Ladakh, Western Himalayas

-

1a stems only above-ground................................................................................................................2

-

1b stems also below-ground................................................................................................................7

-

2a neither adventitious roots nor buds present on roots (non-clonal plants)...............................................3

-

2b horizontal rooting stem...................................................................................................................4

-

2c plant fragments...............................................................................................................................5

-

3a annual and biennial herbs (“Microula tibetica” type)

-

3b trees (“Juniperus semiglobosa” type)

-

3c cushion plants (“Thylacospermum caespitosum” type)

-

4a horizontal stems short-lived (up to two growing seasons)

-

Short-lived horizontal rooting stems on or above soil surface:

-

short-lived herbaceous clonal growth organ rooting in the soil and providing connection between offspring plants or formed by creeping axis; nodes on stem bearing leaves, internodes usually long, stem serving as a storage organ and bud bank; vegetative spreading usually fast and persistence low (“Halerpestes sarmentosa” type)

-

4b horizontal stems long-lived (more than two growing seasons)

-

Long-lived horizontal rooting stems on soil surface:

-

long-lived, usually woody, clonal growth organ formed by creeping axis, rooting in the soil; nodes of youngest parts bearing leaves, internodes shorter than in short-lived horizontal stems; stem serving as a storage organ and bud bank; vegetative spreading slow and persistence high (“Thymus linearis” type)

-

5a plant fragments specialized for overwintering (turions)

-

Turions:

-

detachable over-wintering buds (usually in water plants) composed by tightly arranged leaves filled with food reserves; turions, developing axially or apically and needing vernalisation to re-growth (“Potamogeton amblyphyllus” type)

-

5b unspecialized plant fragments

-

Plant fragments of stem origin:

-

detached parts of shoot with rooting ability (“Potamogeton perfoliatus” type)

-

5c detachable offspring........................................................................................................................6

-

6a offspring in inflorescence (pseudovivipary)

-

Plantlets (pseudovivipary):

-

meristem normally develops into a flower, but forms vegetative buds (plantlets, bulbils, root or stem tubercules), which are sometimes soon detached from the parent plant; alternatively the entire inflorescence falls off and the plantlets root at the soil surface; offspring size similar to seedlings (“Bistorta vivipara” type)

-

6b offspring in axils of leaves

-

Axillary buds:

-

small vegetative diaspores produced in axils of leaves on stems above-ground formed by axillary buds subtended by small storage organ of stem, root (tubercule) of leaf (bulbil) origin; buds soon shed from mother plant, beginning to grow immediately; resembling seedlings in size (“Saxifraga cernua” type)

-

7a below-ground stems lacking adventitious roots and roots lacking adventitious buds.............................................................................................................................................8

-

7b below-ground stems possessing adventitious roots and/or roots possessing adventitious buds.............................................................................................................................................9

-

8a long below-ground stems (pleiocorm)

-

Pleiocorm having long branches:

-

plant possessing a primary root system lacking adventitious roots and buds; tap root serving as storage organ; bud bank situated on perennial stems with long (more than 10 cm) branches serving as vascular link between shoots and primary root; non-clonal plants (“Saussurea gnaphalodes” type)

-

8b short below-ground stems (pleiocorm)

-

Pleiocorm having short branches:

-

plant possessing a primary root system lacking adventitious roots and buds; tap root serving as storage organ; bud bank situated on perennial stems with short (less than 10 cm) branches serving as vascular link between shoots and primary root; non-clonal plants (“Arnebia euchroma” type)

-

9a roots with adventitious buds.........................................................................................................10

-

9b roots without adventitious buds....................................................................................................11

-

10a adventitious buds on main root

-

Main root with adventitious buds:

-

main root (include hypocotyle) forming adventitious buds spontaneously or after injury; clonal growth usually only after fragmentation of main root (“Parrya nudicaulis” type)

-

10b adventitious buds on horizontal creeping roots

-

Horizontal roots with adventitious buds:

-

branches of main root and adventitious roots forming adventitious buds spontaneously or after injury; roots serving as bud bank and vascular connection between offspring shoots; lateral spread usually extensive; persistence differing among species (“Ptilotrichum canescens” type)

-

11a below-ground stems lacking specialized storage organs............................................................12

-

11b below-ground stems possessing specialized storage organs, stems sometimes reduced.............15

-

12a stems formed below-ground (hypogeogenous rhizomes)...........................................................13

-

12b stems formed at soil surface and older parts placed below-ground (epigeogenous rhizomes)...................................................................................................................................14

-

13a hypogeogenous rhizomes with short increments (less than 10 cm)

-

Short hypogeogenous rhizomes:

-

perennial organs of stem origin formed below-ground; rhizome usually growing at a species specific depth, periodically becoming orthotropic and forming above-ground shoots; horizontal part of the rhizome bearing bracts, some roots and possessing short internodes; vegetative spreading intermediate; persistence differing considerably among species (“Leontopodium ochroleucum” type)

-

13b hypogeogenous rhizomes with long increments (more than 10 cm)

-

Long hypogeogenous rhizomes:

-

perennial organs of stem origin formed below-ground; rhizome usually growing at a species-specific depth, periodically becoming orthotropic and forming above-ground shoots; horizontal part of the rhizome bearing bracts, some roots possessing long internodes; vegetative spreading fast; persistence differing considerably among species (“Poa tibetica” type)

-

14a Short epigeogenous rhizomes:

-

perennial organ of stem origin formed above-ground; its distal part covered by soil and litter or pulled into the soil by contraction of roots; nodes bearing green leaves; internodes usually short; rhizomes bearing roots and serving as a bud bank and storage organ; vegetative spread low (up to one cm per year); persistence usually low; typical of tussock grasses (“Festuca kashmiriana” type)

-

14b Medium long epigeogenous rhizomes:

-

perennial organ of stem origin formed above-ground; its distal part covered by soil and litter or pulled into the soil by contraction of roots; nodes bearing green leaves; internodes usually short; rhizomes bearing roots and serving as a bud bank and storage organ; vegetative spread low (up to a few cm per year); persistence usually low (“Cremanthodium ellisii” type)

-

14c Long epigeogenous rhizomes:

-

perennial organ of stem origin formed above-ground; its distal part covered by soil and litter or pulled into the soil by contraction of roots; nodes bearing green leaves; internodes usually short; rhizomes bearing roots and serving as a bud bank and storage organ; vegetative spread low (up to a few cm per year); persistence usually long, resulting in a large preserved rhizome system (“Biebersteinia odora” type)

-

15a storage in leaves

-

Bulbs:

-

storage and perennation organ consisting of storage leaves and shortened stem base; stem providing bud bank and connection between offspring shoots; lateral spread low (“Lloydia serotina” type)

-

15b storage in stem

-

Stem tubers:

-

below-ground, usually short-lived storage and regenerative organ of shoot origin; lateral spread high in the case of offspring tubers formed on hypogeogenous rhizome, persistence usually low (“Potamogeton filiformis” type)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klimešová, J., Doležal, J., Dvorský, M. et al. Clonal Growth Forms in Eastern Ladakh, Western Himalayas: Classification and Habitat Preferences. Folia Geobot 46, 191–217 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12224-010-9076-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12224-010-9076-3