Abstract

Our research uniquely shows that scarcity cues, when effectively managed by the service firms, can lead to favorable purchase decisions. We investigate how service firms that are scarce on time resource (busy) vs. money resource (poor) are perceived differentially on the two basic dimensions of social perceptions: warmth and competence. Across four studies, we provide the first empirical evidence that busy service firms are perceived higher on competence and poor service firms are perceived higher on warmth. We also find that service firms that are both busy and poor have the highest purchase preference compared to either busy or poor service firms. In addition, purchase preferences are moderated by the consumption contexts (exchange vs. communal relationship domain). Managerially, our findings that scarcity cues influence purchase preferences can benefit the design and execution of marketing strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Service firms play a crucial role in the US economy and account for two-thirds of its GDP (Atlantic, 2018). Extant research highlights that service firms need resources to conceive and implement strategies that improve efficiency and effectiveness (e.g., Barney, 1991). In reality, service firms often experience scarcity of resources. The prevalence of scarcity of money and time resources is ubiquitous phenomena as evidenced by apps like Opentable and Yelp reviews by consumers that highlight such scarcity. Similarly, in the United States, government policies like tax deductions and other financial incentives are often designed to help firms that might be scarce on money resources during the events such as pandemics. Despite the prevalence of the busy firms (with limited time resource) and poor firms (with limited money resource), yet, we know little about how consumers view such scarcity of resources and the downstream purchase consequences. We investigate how service firms can effectively manage consumer perceptions of such scarcity to induce favorable purchase decisions. Specifically, our research examine how these scarcity cues impact warmth (i.e., what are their intentions) and competence (i.e., are they capable) perceptions of these service firms and consequent purchase decision making.

The present research makes several contributions to both theory and practice of marketing (Table 1). First, this research provides initial evidence that money and time resource scarcity cues have critical consequences for social perceptions of warmth and competence perceptions respectively. Thus, we identify a novel antecedent, scarcity cues, that influences consumer perceptions of service firms and purchase decisions. Second, while past research has highlighted that competitive advantage is gained by having abundant resources (Slotegraaf et al., 2003), we show that under certain conditions, consumers may favorably view scarcity in resources for service firms. Third, our research shows that consumers’ purchase preferences are higher when service firm has money and time scarcity compared to service firm that has only money and only time scarcity. Finally, we identify specific consumption contexts (i.e., exchange vs. communal) that moderate the relevance of warmth and competence in purchase decisions. Our findings suggest that managers could incorporate scarcity cues in their marketing strategy such as highlighting specific consumer reviews to evoke specific consumer perceptions and impact purchase decisions.

Theoretical background

Money versus time resource

“Money and time are arguably the two resources that we humans most frequently make decisions about throughout our lives” (Macdonnell & White, 2015, p. 551). We focus this investigation on these two essential resources to consumer behavior – money and time (Lynch et al. 2010). Money and time are present in consumer’s everyday decisions (Zauberman & Lynch, 2005). People often “want more money and time, but unfortunately there is rarely an opportunity to simultaneously gain in both” (Hershfield et al., 2016, p. 697). In accord, past research has viewed money and time as orthogonal constructs since the decision making process regarding time is different from decision making process regarding money (Leclerc etal., 1995; Liu & Aaker, 2008; Okada & Hoch, 2004; Soman, 2001). People think about money and time in profoundly different ways (e.g., Whillans et al., 2016) such as money is more fungible than time (Leclerc et al., 1995). Similarly, other factors such as activated mindsets (Liu & Aaker, 2008), value of resources (Okada & Hoch, 2004), and mental accounting of resources (Soman, 2001) also differentiate money and time resource.

The above review suggests that money and time are two important resources. In this research, we examine the scarcity of these important resources in the context of service firms. While past research has examined money and time as orthogonal, we also consider the possibility that money resource and time resource can be correlated. In the next section, we highlight unique features of service firms.

Service firms

It is widely documented that service firms have several distinct characteristics (e.g., Zeithaml et al., 1985). Services involve engagement with consumers and feature interpersonal behavior. The high degree of interaction between consumer and service employees implicates perishability that is services cannot be stored or inventoried. For instance, dinner tables at restaurants that are not used cannot be reclaimed. The interpersonal interaction “complicates the predictability of time required in the service experience and the service organization’s ability to match capacity and demand” (Booms & Bitner, 1981; Bowen & Ford, 2002, p. 455–456).

Service firms are often assessed on two aspects i.e., core of the service and relationship aspect (Iacobucci & Ostrom, 1993). The core of a service is “that part of the service we think of when we name the service” (Iacobucci & Ostrom, 1993, p. 258). For instance, the dinner served at a restaurant will be evaluated by quality and flavor of the food. In other words, the core of the service focuses on competence and efficiency. The relationship aspect of a service “describes the interpersonal process by which the service is delivered” (Iacobucci & Ostrom, 1993, p. 258). For instance, the warmth and friendliness of a waiter.

The above review suggests that service firms are characterized by unique features. The current research focuses on scarcity of two fundamental resources that service firms use to achieve their goals – money and time.

Money and time resources in service firms

Past research highlights that service firms need resources to conceive and implement strategies that improve efficiency and effectiveness (e.g., Barney, 1991). This perspective, grounded in the resource-based view of the firm (Wernerfelt, 1984), emphasizes the possession of resources as being indispensable for enhancing the value of the service firm and providing competitive advantage. We examine two service firm related resources – money and time – that are essential for providing services (Barney, 1991; Mulligan, 1997; Ryan, 2017; Zeithaml et al., 1985). Money resource is an essential resource of the service firm that characterizes the amount of cash that is available to ensure that the firm is able to provide services. The accounting for money is a routine activity for businesses such that “businesses are mandated to keep accounts of monetary expenses” and “money is treated as a factor of production” (Soman, 2001, p. 171). Past research highlights that money resource is important in determining firm’s business performance (de Jong et al. 2021; Morgan, 2012). In addition, as noted, a unique aspect of service firms is perishability, or the fact that services cannot be stored or inventoried. Since services involve performances or processes that cannot be stockpiled, time resource becomes an important feature of service firms.

In sum, money and time are two important resources for service firms. While money and time resources are highly valued, however, service firms often experience scarcity of resources.

Scarcity of money and time resources

“Money and time are both lamentable constraints in life, as well as our principal means of attaining and experiencing what life has to offer” (Macdonnell & White, 2015, p. 551). “Resource scarcity is an increasingly pressing problem” (Hosany & Hamilton, 2022; Lee-Yoon et al., 2020, p. 391; Sarial et al., 2021). Many firms often state that they do not have adequate money or time to meet the demands of consumers (BBC, 2021; Knoll, 2020; Ong, 2020).

Scarcity in firm’s resources is defined as the difference between firm’s present level of resource available and a higher, more appropriate level of resource (Cannon et al., 2019). Consumers often observe such scarcity by comparing the present state of the target firm to the state of comparable firms (Sharma & Alter, 2012; Sharma et al., 2014). In our context, we define service firms have ‘scarcity in time resource’ when firms’ level of time resource available is perceived to be lower compared to other firms. In contrast, service firms have ‘scarcity in money resource’ when firms’ level of money resource available is perceived to be lower compared to other firms.

Service firm related scarcity of time resource can be caused due to time bound surge in demand such as holidays, seasonality, tourist season, etc. (Kimes & Wirtz, 2002) or due to limited supply such as operational limitations (Ong, 2020). Similarly, service firm related scarcity of money resource can be caused due to excess demand such as higher cost of raw materials (Tappe, 2021) or due to limited supply such as financial crises induced budgetary cuts (Bicen & Johnson, 2014).

Service firm related scarcity of time resource can be caused due to naturally occurring reasons such as limited reservations due to weekend demand or due to deliberate reasons such as giving out limited reservations. Similarly, service firm related scarcity of money resource may also be triggered due to naturally occurring reasons such as financial crises induced budgetary cuts and inflation, or due to deliberate reasons such as services offered at reduced prices or when prices are not increased in light of increasing cost of raw materials.

The service firm related scarcity could be highlighted by consumers such as through word-of-mouth, crowdfunding appeals (Adams, 2020; Xiang et al., 2019), etc. For instance, Jessica (a consumer at Punjabi Deli) launched GoFundMe crowdfunding when Punjabi Deli was impacted by Covid-19 (Eater, 2020). These service firm related scarcity of money resource could also be pointed out by media reports. For instance, a media report highlighted how Chinatown businesses in New York have faced scarcity of money resource (Stieg, 2020).

Scarcity cues can exist on a continuum from purely time resource scarcity cues to purely money resource scarcity cues (Hershfield et al., 2016). In our research, we treat scarcity cues as showing either time scarcity or money scarcity or none. As noted, service firm related scarcity of money resource can be highlighted using cues such as crowdfunding appeals focusing on financial distress and service firm related scarcity of time resource can be highlighted using cues such as limited availability as indicated by lack of time slots. Thus, firms can be scarce on either money or time resource. However, the firm that is scarce on money resource may as well be scarce on time resource too. Hence, we also examine the possibility when both money and time resources are scarce.

Relevant to our research, when firms are scarce in money resource, these firms are seen as being without an economic agenda, not solely motivated by profit, and lacking greed (Grégoire et al., 2010). They are also likely to induce subsequent association with other-centeredness and altruistic motives (Ellen et al., 2006). Thus, scarcity of money is more aligned with the relationship aspect of a service.

As noted, time resource is essential for firms to provide comprehensive service to consumers (Zeithaml et al., 1985). This is because time resource, by its definition, involves performances and activities that the services are comprised of (Berry, 1980). Thus, time scarcity implies that service firm providing service to one consumer precludes the service firm from providing service to another consumer. When service firms experience time scarcity, it increases delay in providing service to potential consumers. Hence, when service firms appear to be scarce on time resource, consumers may infer that service firms are ‘in demand’ by other consumers. Hence, scarcity of time is more aligned with the core of a service that focuses on competence and efficiency.

In sum, service firms often experience scarcity of money and time resources and scarcity of resources is detrimental for service firms. We explore the intriguing possibility that consumer perceptions can be managed to induce have more favorable perceptions of service firm related scarcity. We examine how two major firm related scarcities of time and/or money resources will be perceived and evaluated by the consumers. In this research, we consider the implications of service firm related scarcity on two basic dimensions of social perceptions – warmth and competence – that are used to assess other people.

Social perceptions: Warmth and competence

A significant body of social psychology research has found that individuals make sense of social groups around them along two fundamental dimensions- by assessing the intention of others, characterized by warmth dimension, and by assessing the likelihood in carrying out the intention, characterized by competence dimension (Fiske et al., 2002, 2007). In particular, the warmth dimension is used to assess traits like friendliness and trustworthiness. The competence dimension, in contrast, is used to assess traits like efficiency and skill. These dimensions guide social perceptions and elicit specific emotions and differential behaviors towards the target group (Cuddy et al., 2007). Individuals use these dimensions to assess themselves, other groups, nations, and social objects (Chen et al., 2014). Past research in consumer psychology has shown that the two dimensions of social perceptions can also be used to interpret and assess information about firms (Kervyn et al., 2012; Yang & Aggarwal, 2019). Emerging research has pointed out that specific brand-related cues may predict warmth and competence perceptions. Yang and Aggarwal (2019) showed that small sized companies are associated with higher warmth inferences, and this association has implications for evaluations. Thus, it appears that specific cues may lead to differential consumer perceptions and downstream consequences in terms of evaluations and purchase preferences. Similarly, these findings are compatible with the framework that service firms are evaluated in terms of two aspects- core and relationship (Iacobocci & Ostrom, 1996). In other words, the core aspect can be conceptualized as related to competence and relationship aspect can be conceptualized as related to warmth. However, the importance and downstream consequences of warmth and competence in the context of service firms have not been systematically investigated.

In sum, warmth and competence are two primary dimensions of social perception. In this research, we examine how money and time scarcity cues of service firms will affect warmth and competence perceptions of service firms.

Hypotheses development

Scarcity cues and consumer perceptions of service firms

Past research has pointed out that busy firms promote unique norms and behavioral patterns aimed at being task oriented (Rafaeli & Sutton, 1990; Sutton & Rafaeli, 1988). In a qualitative investigation, Sutton and Rafaeli (1988) found support for the premise that busy stores are more focused on task and efficiency and are less friendly. In their interviews with clerks in busy stores, the clerks agreed that friendly expressions were not essential and were less likely to engage in greetings, smiling, thanking, and establishing eye contact with customers since these expressions were perceived to hamper efficiency. Further, consumers are also more likely to focus on the core of the service (i.e., competence related traits) and less likely to focus on the friendliness cues in the busy stores (Grandey et al., 2011). When consumers visit such firms, they are likely to observe the focus on competence and hence, regard these firms high on competence. Thus, busy firms are more focused on quality and efficiency as well as consumers are more perceptive of the competence dimension of social perception.

In addition, as noted, when service firms appear to be scarce on time resource, consumers consider these service firms to be ‘in demand’ by other consumers and scarcity of time resource is aligned with the core of a service. Hence, we predict that busy service firms will be considered high on competence.

There is some evidence that firms that are associated with social objectives are considered high on warmth perceptions. For instance, past research has suggested that non-profits, because of their commitment to social objectives, are considered to be warmer than for-profit brands (Aaker et al., 2010). In an experiment, participants read a description about a product that was made either by a non-profit organization (e.g., www.mozilla.org) or for-profit organization (e.g., www.mozilla.com). Participants rated non-profit organizations as higher on warmth and generosity perceptions compared to for-profit organizations (Aaker et al., 2010, study 1). Another correlational study found that brands that were subsidized by government, for instance USPS, Veterans Hospital, Amtrak, and Public Transportation, were perceived as having positive intentions (Kervyn et al., 2012). Similarly, the small size of the firm is also associated with warmth perceptions (Yang & Aggarwal, 2019). Thus, past research has shown that high warmth perceptions are associated with firms having specific characteristics such as social objectives (Torelli et al., 2012).

Interestingly, none of the studies have examined another enduring characteristic often associated with firms that have social objectives and are smaller in size, limited money resource. We investigate the possibility that scarcity of money resource is yet another factor that may be instrumental in inducing warmth perceptions. As noted, when firms are scarce in money resource, these firms are seen as other-centered and more aligned with the relationship aspect of a service. Thus, we predict that firms lacking money resource will evoke higher warmth perceptions.

While we have discussed the consequences of the scarcity of either money or time resource on warmth and competence perceptions respectively, it is likely that both money and time scarcity may occur concurrently in some situations. Taken together, when scarcity of money cues are accompanied by scarcity of time cues, we suggest that money and time scarcity will have an additive effect such that the firm will be perceived as higher on both warmth and competence.

H1a

Service firm that is scarce on only money resource is judged as higher on warmth.

H1b

Service firm that is scarce on only time resource is judged as higher on competence.

H1c

Service firm that is scarce on money and time resource is judged as higher on warmth and competence.

Scarcity cues and purchase decisions

In the service firm context, the goal of the interaction is to receive service and hence, the interaction is more formal, work related and economic in nature (Grandey et al. 2005; Iacobucci & Ostrom, 1993; Parasuraman et al., 1985). Past research has shown that high levels of task performance and warmth (or authenticity) leads to higher customer satisfaction (Grandey et al. 2005). In a study using video vignettes of hotel check-in encounter to manipulate clerk’s task performance (by providing accurate vs. inaccurate information) and authenticity (by providing genuine vs. fake smiles), Grandey et al. 2005 (study 1) found that genuine smiles had an additive impact on customer satisfaction only when tasks were performed well. We examine the simultaneous impact of scarcity of money and time resource in service firms. Based on the above research, we expect that when scarcity of time cues are accompanied by scarcity of money cues, such firms will be more preferred in purchase decisions since warmth perceptions have an additive impact on purchase decisions.

H2

Service firm that is scarce on money and time resource has higher purchase preferences compared to service firm that is scarce on only money, scarce on only time, or control condition.

The moderating role of consumption contexts and purchase decisions

Social perception is contextually dependent, and the degree to which individuals utilize and consider warmth and competence perceptions in their social assessments is dynamic and differs across situations (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007). We suggest that the distinction highlighted in the social psychology literature between communal and exchange relationship contexts will be useful in determining the relevance of specific dimensions of social perceptions (Clark & Mills, 1993). The communal relationship contexts are governed by social considerations and people have a genuine concern for the other's welfare (Clark & Mills, 1993). In contrast, the exchange relationship contexts are governed by economic considerations and involve profit maximization (Clark & Mills, 1993). In particular, relationships for business purposes are typically characterized as exchange relationships whereas family and friendship relationships are generally characterized as communal relationships (Aggarwal, 2004). In addition, specific relationship contexts lead to differences in importance and relevance assigned to social perception dimensions (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007). Relevant to our research, communal and exchange relationship contexts correspond with warmth and competence perceptions respectively. Specifically, communal relationship contexts lead to greater relevance of warmth perceptions while assessing the firm, whereas exchange relationship contexts lead to greater relevance of competence perceptions while assessing the firm.

H3a

Service firm that is scarce on money resource has higher purchase preferences in communal relationship (vs. exchange relationship) context.

H3b

Service firm that is scarce on time resource has higher purchase preferences in exchange relationship (vs. communal relationship) context.

Summary of studies

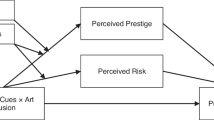

Four studies were conducted to test the proposed hypotheses (Fig. 1). Studies 1 and 2 examined whether firms that are scarce on time resource vs. money resource are perceived differently on their warmth and competence perceptions. In particular, we assessed whether firms that appear scarce on time resource are perceived to be more competent, while firms that appear scarce on money resource are perceived to be warmer, as detailed in H1a and H1b. Study 3 examined the combined effect of money and time scarcity cues on warmth and competence perceptions (H1c). Study 3 also examined the downstream consequences of scarcity of money and time among service firms on purchase decisions as detailed in H2. Study 4 assessed whether the consumption context moderated the impact of scarcity cues on purchase preferences (H3a and H3b).

Study 1: Perceptions of hair salons

Study 1 featured hair salons and presented scarcity cues in terms of money or time and examined the implications for warmth and competence perceptions. Specifically, we assessed whether presenting as a poor firm increases warmth rating compared to the control group and presenting as a busy firm increases competence ratings compared to the control group as predicted in H1a and H1b.

Method

Participants

One hundred and eighty nine participants from a large university in US (Mage = 19.66, SDage = 0.89, 46.6% females) completed this study for course credit. Participants were randomly presented with one of the three conditions that varied on scarcity cues- scarcity of time condition, scarcity of money condition, or control condition.

Procedure

Participants were asked to imagine that they had decided to go to a hair salon. They were told that they will be presented with brief comparative profiles of three randomly selected hair salons and the next availability for booking service at these hair salons. Participants were presented with either busy, poor, or control condition.

The profiles of the hair salons included a short description of the hair salon, company details including net income, and information about the next availability of the hair salon (adapted from Yang & Aggarwal, 2019). In the busy condition, we varied the availability of the focal salon such that the focal salon was less available compared to the other two hair salons. Specifically, in the busy condition, the focal hair salon was next available after one month in comparison to the other two hair salons, which were next available the following day. In the poor condition, we varied the net income of the focal salon such that the focal salon had a lower net income compared to the net income of the other two hair salons. Specifically, in the poor condition, the focal hair salon had lower net income (i.e., $4,000) in comparison to the other two hair salons (e.g., $45,000). In the control condition, the focal hair salon had similar availability and had similar net income in comparison to the other two hair salons.

Participants were then asked to rate the focal salon on two measures of warmth and competence perceptions. For the first measure of warmth and competence perceptions, they rated the salon on three traits to comprise the warmth index (warm, kind, and understanding (α = 0.90)) and three traits to comprise the competence index (competent, effective, and efficient (α = 0.82); adapted from Aaker et al., 2010). For the second measure of warmth and competence perceptions, participants assessed the salon on two items about intentions of the salon (“has good intentions toward ordinary people” and "consistently acts with the public’s best interests in mind” (α = 0.81) on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much) based on Kervyn et al. (2012). Participants also evaluated the salon on two items about the ability of the salon (i.e., “has the ability to implement its intentions” and “is skilled and effective at achieving its goals” (α = 0.79) on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; Kervyn et al., 2012).

At the end of the study, participants completed the manipulation checks, where they were asked to rate the extent to which the focal hair salon appeared scarce on money, assessing the manipulation of the poor condition on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Similarly, participants were asked to rate the extent to which the focal hair salon appeared scarce on time, assessing the manipulation of the busy condition on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Participants also answered the questions on the believability of the description of the hair salons. Finally, they completed the demographic information about age and gender.

Results

Manipulation checks

An independent samples t-test was conducted on the portrayal of money resource scarcity. The results confirmed the efficacy of the manipulation of the poor salon. As expected, participants in the poor condition thought that the focal firm was presenting money scarcity compared to busy condition (MPoor = 4.89, SD = 1.70; MBusy = 3.16, SD = 1.30; t(128) = 6.53, p < 0.001). In addition, another independent samples t-test was conducted on the portrayal of time resource scarcity, confirming the efficacy of the manipulation of the busy firm. As expected, participants in the busy condition thought that the focal salon was presenting time scarcity compared to poor condition (MBusy = 5.84, SD = 1.31; MPoor = 3.23, SD = 1.79; t(128) = 9.49, p < 0.001). The independent samples t-test that was conducted on believability measure showed that participants in two conditions rated the description to be similar on believability (MPoor = 4.76 SD = 1.31; MBusy = 4.91, SD = 1.40; t < 1).

Warmth and competence perceptions

A one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on warmth perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among warmth perceptions for the three cue conditions (F(2, 187) = 4.99, p < 0.01). Specifically of interest, follow up analyses showed that participants rated poor salon to be higher on warmth ratings compared to the control condition (MPoor = 4.96, SD = 1.28; MControl = 4.23, SD = 1.28; t(124) = 3.14, p < 0.01), supporting H1a.

Similar one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on the social perceptions of competence. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among competence perceptions for the three cue conditions (F(2, 187) = 5.03, p < 0.01). As expected, follow up analyses showed that participants rated the busy salon to be higher on competence ratings compared to control condition (MBusy = 5.21, SD = 1.43; MControl = 4.51, SD = 1.08; t(122) = 2.97, p < 0.01), supporting H1b (see Fig. 2).

Intentions and ability perceptions

The one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on the intention perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among intention ratings for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 187) = 8.51, p < 0.001). Follow up analyses showed that, as expected, participants rated the poor salon to have better intentions compared to the control condition (MPoor = 5.11, SD = 1.25; MControl = 4.23, SD = 1.09; t(124) = 4.05, p < 0.001).

Similar one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on ability perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among ability perceptions for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 187) = 5.79, p < 0.01). Specifically of interest, follow up analyses showed that participants rated the busy salon to have higher ability compared to the control condition (MBusy = 5.37, SD = 1.15; MControl = 4.63, SD = 1.22; t(122) = 3.40, p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study provided support for the differential social perceptions of the busy and poor firms. Busy firms were perceived to be higher on competence perceptions compared to the baseline, whereas poor firms were perceived to be higher on warmth perceptions compared to the baseline. In other words, while presenting scarcity of time resource enhanced perceptions of the firm’s competence and ability, firms depicting scarcity of money resource are perceived to have good intentions and higher warmth perceptions.

Study 2: Perceptions of restaurants

Study 2 further examines the systematic differences in perceptions of the busy and poor firms by featuring another service firm category, restaurants, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the findings.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and five participants from mTurk (Mage = 40.30, SDage = 13.18, 56.1% females) completed this study for a small monetary compensation. Participants were randomly presented with one of the three conditions that varied on scarcity cues- scarcity of time condition, scarcity of money condition, or control condition.

Procedure

Similar to Study 1, participants were asked to imagine that they had decided to go to a restaurant. They were told that they will be presented with brief profiles of three randomly selected restaurants and the next availability for reserving a table at these restaurants. Participants were presented with either busy, poor, or control condition.

The profiles of the restaurants included a short description of the restaurants, company details including net income, and information about the next availability of the restaurant. In the busy condition, we varied the availability of the focal restaurant such that the focal restaurant was less available compared to the other two restaurants. Specifically, in the busy condition, the focal restaurant was next available after one week, in comparison to the other two restaurants that were next available the following day. In the poor condition, we varied the net income of the focal restaurant such that the restaurant had lower net income compared to the net income of the other two restaurants. Specifically, in the poor condition, the focal restaurant had net income of $20,000, in comparison to the other two restaurants of $45,000. In the control condition, the focal restaurant had similar availability and had similar net income to the other two restaurants.

Similar to Study 1, participants were then asked to rate the focal restaurant on two measures of warmth and competence perceptions. For the first measure of warmth and competence perceptions, they rated the restaurant on three traits to comprise the warmth index (warm, kind, and understanding (α = 0.91)) and three traits to comprise the competence index (competent, effective, and efficient (α = 0.93); Aaker et al., 2010). For the second measure of warmth and competence perceptions, participants assessed the restaurant on two items about intentions of the restaurant (i.e., “has good intentions toward ordinary people” and “consistently acts with the public’s best interests in mind” (α = 0.86)) on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much) based on Kervyn et al. (2012). Participants also evaluated the restaurant on two items about the ability of the restaurant (i.e., “has the ability to implement its intentions” and “is skilled and effective at achieving its goals” (α = 0.93)) on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; Kervyn et al., 2012).

At the end of the study, participants completed the manipulation checks where they were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on money, assessing the manipulation of the poor firm on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Similarly, participants were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on time, assessing the manipulation of the busy firm on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Participants also answered the questions on the believability of the description of the restaurants. Finally, they completed the demographic information about age and gender.

Results

Manipulation checks

An independent samples t-test was conducted on the portrayal of money resource scarcity, confirming the efficacy of the manipulation of poor condition. As expected, participants in the poor condition thought that the focal restaurant appeared scarce on money compared to the busy condition (MPoor = 4.51, SD = 1.99; MBusy = 3.01, SD = 1.77; t(135) = 4.67, p < 0.001). In addition, another independent samples t-test was conducted on the portrayal of time resource scarcity, confirming the efficacy of the manipulation of busy condition. As expected, participants in the busy condition thought that the focal restaurant appeared scarce on time compared to the poor condition (MBusy = 5.17, SD = 1.90; MPoor = 3.57, SD = 1.78; t(135) = 5.08, p < 0.001). The independent samples t-test, conducted on believability measure, showed that participants in two conditions rated the description to be similar on believability (MPoor = 5.66, SD = 1.45; MBusy = 5.84, SD = 1.18; t < 1).

Warmth and competence perceptions

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on warmth perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among warmth perceptions for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 202) = 3.75, p < 0.05). Specifically of interest, follow up analyses showed that participants rated the poor restaurant higher on warmth ratings compared to the control condition (MPoor = 5.48, SD = 0.93; MControl = 4.94, SD = 1.29; t(134) = 2.73, p < 0.01), further supporting H1a.

A similar one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on the perceptions of competence. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among competence perceptions for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 202) = 4.00, p < 0.05). As expected, follow up analyses showed that participants rated the busy restaurant higher on competence ratings compared to the control condition (MBusy = 5.82, SD = 1.04; MControl = 5.30, SD = 1.39; t(135) = 2.42, p < 0.05), further supporting H1b (see Fig. 3).

Intentions and ability perceptions

The one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on the intention perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among intention ratings for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 202) = 4.41, p < 0.05). Follow up analyses showed that as expected participants rated the poor restaurant to have better intentions compared to control condition (MPoor = 5.50, SD = 1.07; MControl = 4.90, SD = 1.33; t(134) = 2.87, p < 0.01).

Similar one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of scarcity cues on ability perceptions. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference among ability perceptions for the three scarcity cue conditions (F(2, 202) = 3.94, p < 0.05). Specifically of interest, follow up analyses showed that participants rated busy restaurant to have higher ability compared to the control condition (MBusy = 5.55, SD = 1.16; MControl = 4.87, SD = 1.59; t(135) = 2.80, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Consistent with Study 1, we found differential perceptions of the busy and poor firms. Study 2 also provided a more rigorous test for our basic premise by reducing the extent to which the restaurants presented scarcity of time resource and money resource. In particular, the findings showed that busy firms engendered high competence perceptions when the busy firms were next available after one month (Study 1) or one week (Study 2). In addition, poor firms engendered high warmth perceptions when the poor firm’s net income was about one-tenth of the comparison group (Study 1) or half of the comparison group (Study 2).

Study 3: Scarcity of money and time and purchase preferences

In Study 3, we build on the findings from Studies 1 and 2 in the following ways. First, we examine a scenario where service firm experiences both money and time scarcity. We expect that service firm that is poor as well as busy will engender high warmth and competence perceptions (H1c). Second, we examine the downstream consequences of poor and busy firms on purchase preferences. We predict that consumers will have higher purchase preference for a firm that has both money and time scarcity compared to firms that have only money scarcity or only time scarcity or control condition (H2). Third, this study examines the underlying role of warmth and competence perceptions in predicting purchase preferences. Fourth, for greater ecological validity, we use (a) behavioral purchase choice as a consequential dependent variable; (b) representative sample of real consumers; (c) real website-based stimuli; and (d) the context of real service firms. Fifth, for greater generalization, we use consumer’s reviews to manipulate scarcity of money and time.

Method

Participants

A representative sample of New York residents was recruited for the study by market research agency. Four hundred eighteen participants completed the study for monetary compensation (ages 18–87; Mage = 42.54, SDage = 16.78, 52.2% females; 68% with at least a Bachelor’s degree; 59.6% with household income below $100 K). Participants were presented with one of the four conditions that varied on scarcity cues- scarcity of money as well as time (i.e., poor-busy condition), scarcity of only money (poor condition), scarcity of only time (busy condition), and control condition.

Procedure

All participants learned that they would be shown the Yelp webpage. The Yelp webpage was adapted using ChromDevTools that modified the User Interface components of the website (Mathur et al., 2022). The Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) styling (i.e., text format (such as text color and font size) and background images) remained same as the real Yelp webpage. We only changed the textual content of the webpage. The Yelp webpage showed search results of “Best Mexican restaurant near New York.” Top three restaurants in New York that appeared in the search results were shown to the participants. Participants saw consumers’ online reviews for each of the three restaurants.

The consumer’s review for the focal restaurant was modified based on the condition (i.e., poor condition, busy condition, poor-busy condition, and control condition), however, the reviews of the other two restaurants remained the same. In the poor condition, we varied the review of the focal restaurant such that consumer’s review described the restaurant being on the verge of closing many times over the years and described restaurant’s food and drinks as being easy on the wallet. In the busy condition, we varied the review of the focal restaurant such that consumer’s review described the restaurant as being very busy with wait time being 1 to 1.5 h and recommended to book reservation in advance. In the poor-busy condition, the consumer’s review incorporated the review of both poor and busy conditions. In the control condition, consumer’s review was similar to consumers’ reviews of the other two restaurants. These four conditions were selected based on a pretest that ensured that these conditions varied on scarcity cues manipulation but were similar in believability.

After viewing the reviews of the three restaurants, participants were asked to complete a behavioral dependent measure that involved spending real money. Specifically, participants were told that all participants would enter a raffle and two of them would be randomly picked to receive $30 cash voucher. The behavioral dependent measure comprised of choosing a restaurant (out of the three restaurants) where participants wanted to spend their $30 cash voucher. Participants also indicated their purchase intentions for the focal restaurant, i.e., the extent to which they would like to visit the restaurant on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much).

Similar to the earlier studies, participants were then asked to rate the focal restaurant on warmth and competence perceptions. Specifically, they rated the focal restaurant on three traits to comprise the warmth index (warm, kind, and understanding (α = 0.93)) and three traits to comprise the competence index (competent, effective, and capable (α = 0.91); Aaker et al., 2010). Participants completed the manipulation checks where they were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on money using a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Similarly, participants were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on time using a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Participants then completed the demographic information about age, gender, household income, and education. In the end, participants were debriefed that the Yelp webpage was modified for academic research.

Results

Manipulation checks

A one-way ANOVA on money resource scarcity manipulation check revealed significant difference across conditions (F(3, 414) = 38.38, p < 0.001). As expected, participants in the poor condition thought that the focal restaurant was portraying money scarcity compared to busy condition (MPoor = 4.81, SD = 1.68; MBusy = 2.96, SD = 1.69; t(200) = 7.79, p < 0.001) and control condition (MControl = 2.96, SD = 1.85; t(207) = 7.54, p < 0.001). In addition, participants in the poor-busy condition thought that the focal restaurant was portraying money scarcity compared to busy condition (MPoor-busy = 4.86, SD = 1.90; t(207) = 7.61, p < 0.001) and control condition (t(214) = 7.44, p < 0.001).

Similarly, the one-way ANOVA on time resource scarcity manipulation check revealed significant difference across conditions (F(3, 414) = 48.11, p < 0.001). As expected, participants in the busy condition thought that the focal restaurant was portraying time scarcity compared to poor condition (MBusy = 5.47, SD = 1.64; MPoor = 3.15, SD = 1.85; t(200) = 9.39, p < 0.001) and control condition (MControl = 3.10, SD = 1.92; t(201) = 9.40, p < 0.001). In addition, participants in the poor-busy condition thought that the focal restaurant was portraying time scarcity compared to poor condition (MPoor-busy = 4.95, SD = 1.71; t(213) = 7.41, p < 0.001) and control condition (t(214) = 7.48, p < 0.001).

Warmth and competence perceptions

A one-way ANOVA on warmth perceptions revealed significant difference across conditions (F(3, 414) = 20.91, p < 0.001). As expected, in the poor condition, the focal restaurant was perceived warmer compared to control condition (MPoor = 5.68, SD = 1.23; MControl = 4.47, SD = 1.50; t(207) = 6.35, p < 0.001). In addition, in the poor-busy condition, the focal restaurant was perceived warmer compared to control condition (MPoor-busy = 5.60, SD = 1.29; t(214) = 5.95, p < 0.001).

Similarly, the one-way ANOVA on competence perceptions revealed significant difference across conditions (F(3, 414) = 15.22, p < 0.001). As expected, in the busy condition, the focal restaurant was perceived more competent compared to control condition (MBusy = 5.53, SD = 1.04; MControl = 4.51, SD = 1.59; t(201) = 5.36, p < 0.001). In addition, in the poor-busy condition, the focal restaurant was perceived more competent compared to control condition (MPoor-busy = 5.61, SD = 1.35; t(214) = 5.47, p < 0.001).

Behavioral dependent measure

A logistic regression on the purchase choice (1 = focal restaurant; 0 = other restaurants) revealed significant difference across conditions (Wald's χ2(3, N = 418) = 19.32, p < 0.001). As expected, in accord with H2, participants in the poor-busy condition (57.7%) were more likely to choose the focal restaurant compared to the poor condition (41.3%; χ2(1, N = 215) = 5.66, p < 0.05), busy condition (42.9%; χ2(1, N = 209) = 4.53, p < 0.05), and control condition (27.6%; χ2(1, N = 216) = 19.14, p < 0.001).

Purchase intentions

The one-way ANOVA on the purchase intentions revealed significant difference across conditions (F(3, 414) = 11.32, p < 0.001). As expected, participants in the poor-busy condition had higher purchase intentions for the focal restaurant compared to poor condition (MPoor-busy = 6.03, SD = 1.27; MPoor = 5.35, SD = 1.68; t(213) = 3.36, p < 0.01), busy condition (MBusy = 5.48, SD = 1.55; t(207) = 2.80, p < 0.01), and control condition (MControl = 4.85, SD = 1.47; t(214) = 6.32, p < 0.001), supporting H2.

Mediation

To examine the underlying role of warmth and competence perceptions in predicting purchase decisions, we conducted a serial mediation analysis with purchase decision as DV. We employed PROCESS Model 80 (5,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018) with scarcity cues (1 = poor-busy condition; 0 = control condition) as the predictor, both warmth and competence perceptions as the first mediator (in parallel) and purchase intentions as the second mediator, and purchase choice as the dependent variable. The index of serial mediation was significant for both warmth perceptions (β = 0.07, SE = 0.05, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) [0.01, 0.19]) and competence perceptions (β = 0.06, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.16]). These findings indicate that both warmth and competence perceptions impacted purchase intention and purchase intention further influenced purchase decision for poor-busy restaurants (see Fig. 4).

Discussion

Study 3 examined the combined effects of money and time scarcity cues on warmth and competence perceptions and purchase choice. We found that service firm that was scarce on money and time resource had highest purchase preference compared to service firms that were scarce on only money, scarce on only time, or control condition. We also found evidence for the process that scarcity of money and time resource led to higher warmth and competence perceptions that consequently increased purchase preferences. These results highlighted that money and time scarcity cues impacted behavioral purchase choice, suggesting that service firm related scarcity cues could be used to increase consumer’s purchase preferences and subsequently lead to greater revenues and profits for firms. We established the robustness of the findings of earlier studies by providing convergent evidence for the premise that busy firms engender competence perceptions and poor firms evoke greater warmth perceptions.

Study 4: Moderating role of consumption context

In study 4, we examine the interactive effect of scarcity cues and consumption context on purchase preferences. We predict that a firm appearing scarce on time will be evaluated more favorably when there is an exchange relationship (vs. communal relationship) context. In addition, a firm depicting scarcity of money resource will be evaluated more favorably in a communal relationship (vs. exchange relationship) context.

Method

Participants

One hundred and forty-one participants from a large university in the US (Mage = 20.60, SDage = 1.34, 47.5% females) completed this study for course credit. The study was a 2 (scarcity cues: busy vs. poor) × 2 (consumption context: exchange relationship vs. communal relationship) between-subjects design.

Procedure

Participants were told to imagine that they were either meeting a business associate or a friend for a meal. Past research has pointed out that the relationship with “people who interact for business purposes” highlights exchange relationships, whereas “friendships” are generally characterized as communal relationships (Aggarwal, 2004, p. 88). Participants were asked to decide on a restaurant and reserve a table at the restaurant. Similar to study 2, they were told that they will be presented with brief profiles of three randomly selected restaurants and the next availability for booking a reservation at these restaurants. Participants were presented with either a busy or poor firm condition. In the busy condition, we varied the availability of the focal restaurant such that the focal restaurant was less available compared to the other two restaurants. Specifically, in the busy condition, the focal restaurant was next available after one month, in comparison to the other two restaurants that were next available the following day. In the poor condition, we varied the net income of the focal restaurant such that the focal restaurant had a lower net income compared to the net income of the other two restaurants. Specifically, in the poor condition, the focal restaurant had net income of $5,000, in comparison to the other two restaurants’ net income of $50,000.

After viewing the profiles of the restaurants, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they were willing to go to the focal restaurant on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all willing to go, 7 = willing to go). Similar to earlier studies, participants were also asked to rate the focal restaurant on three traits to comprise the warmth index (warm, kind, and understanding (α = 0.87)) and three traits to comprise the competence index (competent, effective, and efficient (α = 0.85); Aaker et al., 2010). At the end of the study, participants completed the manipulation checks, where they were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on money, assessing the manipulation of the poor condition. Similarly, participants were asked to rate the extent to which the focal restaurant appeared scarce on time, assessing the manipulation of the busy condition. Participants also answered the questions on the believability of the description of the restaurants. Finally, they completed the demographic information about age and gender.

Results

Manipulation checks

A 2 (busy vs. poor firm) × 2 (exchange vs. communal relationship) between-subjects ANOVA conducted on the portrayal of money resource scarcity confirmed the efficacy of the manipulation of the poor condition. As expected, participants in the poor condition thought that the focal restaurant was presenting money scarcity compared to busy condition (MPoor = 4.30, SD = 1.55; MBusy = 2.94, SD = 1.55; F(1, 137) = 26.80, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.16). Similarly, the 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA conducted on the portrayal of time resource scarcity confirmed the efficacy of the busy firm manipulation. As expected, participants in the busy condition thought that the focal restaurant was portraying time scarcity compared to poor condition (MBusy = 4.94, SD = 1.56; MPoor = 3.36, SD = 1.57; F(1, 137) = 35.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.21). No other effects were significant. Similar 2 × 2 ANOVA conducted on believability measure was not significant (all Fs < 1) indicating that participants in the four conditions rated the description similar on believability.

Purchase intentions

The 2 × 2 ANOVA on the purchase intentions index revealed a significant two-way interaction between scarcity cues and consumption context (F(1, 137) = 9.99, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.07). Follow-up analyses revealed that there was higher purchase intention for the poor firm in communal relationship context, compared to exchange relationship context (MCommunal = 5.30, SD = 1.67; MExchange = 4.50, SD = 1.00; F(1, 137) = 5.23, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.04), supporting H3a. In contrast, that there was a higher purchase intention for the busy firm in exchange relationship context, compared to communal relationship context (MExchange = 5.37, SD = 1.55; MCommunal = 4.62, SD = 1.54; F(1, 137) = 4.76, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.03), supporting H3b. (see Fig. 5).

Mediation

To examine the underlying relative role of warmth and competence perceptions in predicting purchase intentions and to assess whether mediation paths were moderated for exchange and communal relationship contexts, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis. We employed PROCESS Model 14 (5,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018) with scarcity cues as the predictor, competence and warmth perceptions as the mediator, consumption contexts as the moderator, and purchase intentions as the dependent variable. The index of moderated mediation was significant for both warmth perceptions (\(\beta\) = -0.56, SE = 0.24, 95% CI [- 1.09, -0.15]) and competence perceptions (\(\beta\) = -0.24, SE = 0.14, 95% CI [-0.55, -0.01]; see Fig. 6).

Discussion

In study 4, we examined the effects of scarcity cues and consumption contexts on purchase preferences. We found that busy firms had higher purchase intentions in exchange relationship contexts, whereas poor firms had higher purchase intentions in communal relationship contexts. We also found evidence for the process that busy firms led to higher competence ratings that consequently increased purchase preferences under exchange relationship consumption contexts. In contrast, poor firms led to higher warmth ratings that consequently increased purchase preferences under communal relationship consumption contexts.

General discussion

Managing scarcity is central to service firms. This research examined how service firms that are scarce on money and/or time resource are perceived and how scarcity of resources impacts purchase decisions. Across different operationalizations of time and money scarcity, service firm contexts (real and hypothetical), and managerially relevant dependent measures (behavioral purchase choices and purchase intentions) using variety of samples including representative sample of consumers, online panel participants, and students, we document that busy service firm is perceived to be high on competence and poor firm is perceived to be high on warmth. Service firm that is poor as well as busy is considered high on both warmth and competence and consequently has the highest purchase preference compared to either poor firm or busy firm.

Theoretical contributions

Scarcity of resources is ubiquitous and effectively managing scarcity is central to enhancing the performance of the service firm. may present challenge to the service firms. In this research, we highlight that under certain conditions, consumers may favorably view such scarcity of resources for service firms. We provide the first empirical evidence that busy service firms are perceived high on competence whereas poor service firms are perceived high on warmth. Thus, our work makes several important contributions and helps to better understand the impact of firm-level scarcity of money and time resource in consumer decision making.

This research extends our understanding of stereotypical judgments in marketing contexts based on Stereotype Content Model (SCM) framework (Fiske et al., 2002). The SCM theoretical framework has been adapted to brand context by emphasizing that perceived intentions and ability are important aspects in understanding brand perceptions (Kervyn et al., 2012). Past research has primarily focused on the downstream consequences of warmth and competence perceptions (Chen et al., 2014). In this research, we demonstrate that scarcity of money and time resource may act as an important antecedent that engenders differential service firm perceptions and consequently impacts consumers’ purchase decisions. Hence, we contribute to the service firm literature by proposing the antecedent that is not envisioned in the past literature.

The present research contributes to the scarcity literature. Extant research has shown that product related scarcity induces competence related assessments such as increased perceived value and quality of the products (Brock, 1968; Gierl & Huettl, 2010; Inman et al., 1997; Parker & Lehmann, 2011). It is important to note that this stream of work is about consumers' response to scarcity of goods and not about scarcity of input resources to produce the goods. In contrast, the present research examines consumers' response to scarcity of input resources (e.g., time and money) to provide or produce a service. Diverging from product related scarcity research that views scarcity as monolithic, we identify different types of scarcities at firm level. While product related scarcity only evokes assessments regarding the efficiency and capability of the products, we show that service firm related scarcity also induces assessments regarding warmth perceptions of the firms. We show that consumers engage in distinct decision making processes while evaluating money and time resource scarcity. The interpersonal aspect, that is unique to service firms (versus product), makes it possible to assess the intentions of the firm. In particular, while scarcity of time is more aligned with the competence dimension of social perceptions, scarcity of money is more aligned with the warmth dimension of social perceptions. We also find that specific consumption contexts moderate the relevance of warmth and competence perceptions in purchase decisions.

Past research has highlighted that consumers view scarcity favorably and buy products when they are perceived as scarce (Ang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; John et al., 2018). We document that in the service firm context, “scarce is good” heuristic is most applicable when service firms experience both scarcity of money resource as well as time resource since firms that are both poor and busy have greater purchase preference compared to firms that are only poor or only busy.

At individual level, Bellezza et al. (2017) have indirectly examined time scarcity and have primarily focused on working hard (i.e., work for long hours). Their key finding is that people who overwork are high on human capital characteristics such as ambition, aspiration, and competence. This finding differs from our research in terms of context (individuals vs. service firms), conceptualization of dependent variable (human capital characteristics vs. competence), and time scarcity operationalization (working long hours vs. lack of time resources).

Managerial implications

The findings of this research can inform service firms about the implications of specific firm-level scarcity. While most firms would avoid firm-level scarcity altogether, the current findings suggest that under certain conditions, service firms should embrace resource scarcity and rely on firm-level scarcity cues to cultivate warmth and competence perceptions and enhance purchase preferences. Since warmth and competence perceptions have differential consequences on consumers’ evaluations, we highlight below different ways in which firms can employ scarcity cues to evoke warmth versus competence perceptions.

Word of mouth, such as online reviews, plays a critical role in influencing consumer’s purchase behavior (Bettencourt, 2019). Firms are considering online reviews as essential part of the marketing mix planning and are employing them strategically to influence purchase choices (Dellarocas, 2006; Mayzlin, 2006). A key implication of this research is that firms may be able to use reviews highlighting firm-level scarcity to evoke warmth and competence (Study 3). For example, consumer reviews that highlight firm-level scarcity could be enlisted at the top of their websites and marked as the “top reviews” so that these reviews are read by the consumers first. Similarly, the association of busy and poor service firms with competence and warmth perceptions respectively can be seen in the marketplace. For instance, while pointing out his perceptions about the local restaurants facing scarcity of money resource, Dr. Anthony Fauci highlights, “I feel badly about restaurants losing business, and I feel it's almost a neighborly obligation to keep neighborhood restaurants afloat. Even though I can cook at home, several nights a week I go out for takeout purely to support those places” (Stieg, 2020).

In addition, our findings suggest that scarcity cues of money and time resources can also create strategic advantage by comparing the focal service firm with potential competitors that are non-busy or financially rich using comparative advertising. For example, Amazon Explore offers virtual experiences livestreamed to consumers but their featured experiences category is so busy that they are often “all booked up.” So, Amazon advertisement can suggest that their virtual experience is more in demand. In contrast, the competing program, YouTube travelogues that are typically a vicarious experience, is easily available.

Past research has pointed out that store related cues have implications for consumers’ attitudes and behaviors (Kamran-Disfani et al., 2017). A service firm may use physical evidence that signals scarcity of money or time. For instance, a doctor’s office that often has a long wait time can inform people about the estimated delay via text message indicating that the doctor is sought after by the patients. Similarly, night clubs that often have long lines outside can inform the potential visitors the need to arrive early or make reservations. Such signaling of being time scarce may enhance competence perceptions. Similarly, scarcity of money can be highlighted at the point of purchase such as at store window. For instance, Army & Navy Bags retail store has put the New York times article titled: “What Happened When Henry Yao Almost Went Bust” (Knoll, 2020) on its store window, thus highlighting money scarcity that is likely to evoke warmth perceptions.

As noted, money and time scarcity may provide certain advantages by signaling warmth and competence respectively, however, to achieve optimal return on investment, service firms should also strive to excel in both warmth and competence. For example, a busy restaurant can increase warmth by providing customers, who are waiting to be seated, with a free drink or a free appetizer. Thus, this research provides insights from a consumer perspective on resource scarcity and its implications for marketing strategy for service firms.

Future directions

Some issues emerge from the present research that need further investigation. In our research, we have focused on scarcity cues that clearly highlight either money or time scarcity. However, service firms related scarcity cues could also highlight scarcity of both money and time resources such as limited space or service staff. Further research could examine the impact of these scarcity cues that do not clearly highlight either money or time scarcity and are ambiguous in nature.

Second, in our research, we examine social perceptions of warmth and competence in the United States which is an independent culture. It is likely that downstream consequences may systematically differ for warmth and competence perceptions in a different culture (Mantrala et al., 2012).

While our studies have examined warmth and competence orthogonally, in a competitive marketplace, a minimum level of competence is required to survive. Since consumers believe that competence is necessary for a firm’s survival and profitability in the marketplace, they may expect that all service firms to possess at least moderate levels of competence (Yang & Aggarwal, 2019). Future research can explore whether the perceptions of low competence could have negative spillover effects on warmth perceptions.

The focus of this study is on examining how service firm related scarcity cues impact consumer perceptions and purchase decisions. Future research may address whether the antecedents of scarcity cues, such as whether scarcity cues are naturally occurring or deliberate on the part of the service provider, may have differential impact on purchase decisions.

Our research is focused on service sector, specifically the retailing industry. It will be productive to examine warmth and competence perceptions in other marketing contexts such as salesforce management, couponing, and online contexts (Mantrala et al., 2010). Interestingly, fashion and motion pictures industries, while not part of the service sector, have distinct market dynamics that are relevant to our research (Mantrala et al., 2005). For example, in the fashion industry, resource rich firms like Louis Vuitton have a clear competitive advantage, however, applying warmth and competence framework may provide insights on how poor firms can also gain competitive advantage (Mantrala & Rao, 2001).

Our findings related to warmth are uniquely relevant to service firms due to their interpersonal nature. While consumers may interact with non-service firms, but such interactions are thought to be primarily along competence dimension. While research in marketing has also addressed consumer relationships with brands, such relationships are often static one-sided consumer interaction with brand’s product, whereas consumer relationship with service firms are more interpersonal and reciprocal. For instance, consumer’s relationship with law firm is often more interactive and mutual that can considerably impact the evaluation of legal service. Future research can examine how consumer-brand relationship differs from consumer-service firm relationship.

In sum, our findings suggest that scarcity, while often viewed as a challenge in general, and specifically during economic or socially disruptive periods, could be a signaling cue for warmth and competence and if managed effectively, could provide a major competitive advantage. Service firms can be strategic and creative in how they rely on their resource scarcity to communicate warmth and competence.

References

Aaker, J., Vohs, K. D., & Mogilner, C. (2010). Nonprofits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 224–237.

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 751–763.

Adams, E. (2020). Punjabi deli fans crowdfund $38k in two days to keep the beloved Indian spot open. https://ny.eater.com/2020/8/31/21408501/punjabi-deli-crowdfunding-campaign Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Aggarwal, P. (2004). The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 87–101.

Ang, D., Gerrath, M. H., & Liu, Y. (2021). How scarcity and thinking styles boost referral effectiveness. Psychology & Marketing, 38(11), 1928–1941.

Atlantic (2018). The American economy is experiencing a paradigm shift. https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/citi-2018/the-american-economy-is-experiencing-a-paradigm-shift/2008/ Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Balachander, S., & Stock, A. (2009). Limited edition products: When and when not to offer them. Marketing Science, 28(2), 336–355.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

BBC (2021), How this iconic Manhattan newsstand survived the Covid pandemic https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-59702495 Accessed 1 January 2022.

Bellezza, S., Paharia, N., & Keinan, A. (2017). Conspicuous consumption of time: When busyness and lack of leisure time become a status symbol. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(1), 118–138.

Berry (1980). Service marketing is different. Business, 30 (May-June), 24–29.

Bettencourt, L.A. (2019). Word-of-mouth seeding and marketing mix planning: When is more better? https://www.ama.org/2019/04/29/word-of-mouth-seeding-and-marketing-mix-planning-when-is-more-better/

Bicen, P., & Johnson, W. H. (2014). How do firms innovate with limited resources in turbulent markets? Innovation, 16(3), 430–444.

Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. In J. H. Donnelly & W. R. George (Eds.), Marketing of Services (pp. 47–51). American Marketing Association.

Bowen, J., & Ford, R. C. (2002). Managing service organizations: Does having a “thing” make a difference? Journal of Management, 28(3), 447–469.

Brock, T. C. (1968). Implications of commodity theory for value change. In A. G. Greenwald, T. C. Brock, & T. M. Ostrom (Eds.), Psychological Foundations of Attitudes (pp. 243–276). Academic.

Cannon, C., Goldsmith, K., & Roux, C. (2019). A self-regulatory model of resource scarcity. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 29(1), 104–127.

Chen, C. Y., Mathur, P., & Maheswaran, D. (2014). The effects of country-related affect on product evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(4), 1033–1046.

Chen, T. Y., Yeh, T. L., & Wang, Y. J. (2020). The drivers of desirability in scarcity marketing. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(4), 924–944.

Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (1993). The difference between communal and exchange relationships: What it is and is not. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(6), 684–691.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648.

de Jong, A., Zacharias, N. A., & Nijssen, E. J. (2021). How young companies can effectively manage their slack resources over time to ensure sales growth: The contingent role of value-based selling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(2), 304–326.

Dellarocas, C. (2006). Strategic manipulation of internet opinion forums: Implications for consumers and firms. Management Science, 52(10), 1577–1593.

Eater (2020). Punjabi Deli Fans Crowdfund $38K in Two Days to Keep the Beloved Indian Spot Open https://ny.eater.com/2020/8/31/21408501/punjabi-deli-crowdfunding-campaign

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 147–157.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902.

Gierl, H., & Huettl, V. (2010). Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(3), 225–235.

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must “service with a smile” be stressful? The moderating role of personal control for American and French employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 893–904.

Grandey, A. A., Goldberg, L. S., & Pugh, S. D. (2011). Why and when do stores with satisfied employees have satisfied customers? The roles of responsiveness and store busyness. Journal of Service Research, 14(4), 397–409.

Grégoire, Y., Laufer, D., & Tripp, T. M. (2010). A comprehensive model of customer direct and indirect revenge: Understanding the effects of perceived greed and customer power. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(6), 738–758.

Hamilton, R., Thompson, D., Bone, S., Chaplin, L. N., Griskevicius, V., Goldsmith, K., ... & Zhu, M. (2019). The effects of scarcity on consumer decision journeys. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(3), 532-550.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hershfield, H. E., Mogilner, C., & Barnea, U. (2016). People who choose time over money are happier. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(7), 697–706.

Hosany, A. R., & Hamilton, R. W. (2022). Family responses to resource scarcity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1–31.

Iacobucci, D., & Ostrom, A. (1993). Gender differences in the impact of core and relational aspects of services on the evaluation of service encounters. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(3), 257–286.

Inman, J. J., Peter, A. C., & Raghubir, P. (1997). Framing the deal: The role of restrictions in accentuating deal value. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(1), 68–79.

John, M., Melis, A. P., Read, D., Rossano, F., & Tomasello, M. (2018). The preference for scarcity: A developmental and comparative perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 35(8), 603–615.

Kamran-Disfani, O., Mantrala, M. K., Izquierdo-Yusta, A., & Martínez-Ruiz, M. P. (2017). The impact of retail store format on the satisfaction-loyalty link: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research, 77, 14–22.

Kervyn, N., Fiske, S. T., & Malone, C. (2012). Brands as intentional agents framework: How perceived intentions and ability can map brand perception. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 166–176.

Kimes, S. E., & Wirtz, J. (2002). Perceived fairness of demand-based pricing for restaurants. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(1), 31–37.

Knoll, C. (2020) What happened when Henry Yao almost went bust https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/25/nyregion/nyc-army-navy-bags-coronavirus.html Accessed 24 November 2021.

Kristofferson, K., McFerran, B., Morales, A. C., & Dahl, D. W. (2017). The dark side of scarcity promotions: How exposure to limited-quantity promotions can induce aggression. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), 683–706.

Ku, H. H., Kuo, C. C., & Kuo, T. W. (2012). The effect of scarcity on the purchase intentions of prevention and promotion motivated consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 29(8), 541–548.

Leclerc, F., Schmitt, B. H., & Dube, L. (1995). Waiting time and decision making: Is time like money? Journal of Consumer Research, 22(1), 110–119.

Lee-Yoon, A., Donnelly, G. E., & Whillans, A. V. (2020). Overcoming Resource Scarcity: Consumers’ Response to Gifts Intending to Save Time and Money. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 5(4), 391–403.

Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 543–557.

Lynch, J. G., Jr., Netemeyer, R. G., Spiller, S. A., & Zammit, A. (2010). A generalizable scale of propensity to plan: The long and the short of planning for time and for money. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(1), 108–128.

Macdonnell, R., & White, K. (2015). How construals of money versus time impact consumer charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(4), 551–563.

Mantrala, M. K., & Rao, S. (2001). A decision-support system that helps retailers decide order quantities and markdowns for fashion goods. Interfaces, 31(3_supplement), S146-S165.

Mantrala, M. K., Albers, S., Caldieraro, F., Jensen, O., Joseph, K., Krafft, M., ... & Lodish, L. (2010). Sales force modeling: State of the field and research agenda. Marketing Letters, 21(3), 255-272.

Mantrala, M. K., Basuroy, S., & Gajanan, S. (2005). Do style-goods retailers’ demands for guaranteed profit margins unfairly exploit vendors? Marketing Letters, 16(1), 53–66.

Mantrala, M., Sridhar, S., & Dong, X. (2012). Developing India-centric B2B sales theory: An inductive approach using sales job ads. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 27(3), 169–175.

Mathur, P., Malika, M., Agrawal, N., & Maheswaran, D. (2022). The context (in)dependence of low fit brand extensions. Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429221076840

Mayzlin, D. (2006). Promotional chat on the Internet. Marketing Science, 25(2), 155–163.

Morgan, N. A. (2012). Marketing and business performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 102–119.

Mulligan, C. B. (1997). Scale economies, the value of time, and the demand for money: Longitudinal evidence from firms. Journal of Political Economy, 105(5), 1061–1079.

Okada, E. M., & Hoch, S. J. (2004). Spending time versus spending money. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2), 313–323.

Ong, B. (2020). The 21 most in-demand NYC outdoor dining reservations. https://www.timeout.com/newyork/news/the-21-most-in-demand-nyc-outdoor-dining-reservations-090320 Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50.

Parker, J. R., & Lehmann, D. R. (2011). When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. Journal of Retailing, 87(2), 142–155.