Abstract

BACKGROUND

Improving care coordination is a national priority and a key focus of health care reforms. However, its measurement and ultimate achievement is challenging.

OBJECTIVE

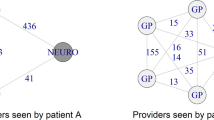

To test whether patients whose providers frequently share patients with one another—what we term ‘care density’—tend to have lower costs of care and likelihood of hospitalization.

DESIGN

Cohort study

PARTICIPANTS

9,596 patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) and 52,688 with diabetes who received care during 2009. Patients were enrolled in five large, private insurance plans across the US covering employer-sponsored and Medicare Advantage enrollees

MAIN MEASURES

Costs of care, rates of hospitalizations

KEY RESULTS

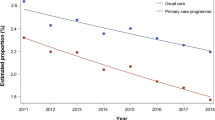

The average total annual health care cost for patients with CHF was $29,456, and $14,921 for those with diabetes. In risk adjusted analyses, patients with the highest tertile of care density, indicating the highest level of overlap among a patient’s providers, had lower total costs compared to patients in the lowest tertile ($3,310 lower for CHF and $1,502 lower for diabetes, p < 0.001). Lower inpatient costs and rates of hospitalization were found for patients with CHF and diabetes with the highest care density. Additionally, lower outpatient costs and higher pharmacy costs were found for patients with diabetes with the highest care density.

CONCLUSION

Patients treated by sets of physicians who share high numbers of patients tend to have lower costs. Future work is necessary to validate care density as a tool to evaluate care coordination and track the performance of health care systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Institute of Medicine. Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

National Priorities Partnership. National Priorities and Goals: Aligning Our Efforts to Transform America's Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2008: http://www.nationalprioritiespartnership.org/uploadedFiles/NPP/08-253-NQF%20ReportLo%5B6%5D.pdf.

Report to Congress. National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

Miller HD. From volume to value: better ways to pay for health care. Health Aff. 2009;28:1418–1428.

Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher E. Primary care and accountable care–two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2301–2303.

Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in Medicare. Health Aff. 2009;28(2):w219–w231.

Rosenthal MB. Beyond pay for performance–emerging models of provider-payment reform. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1197–1200.

National Quality Forum, NQF-Endorsed Definition and Framework for Measuring Care Coordination, http://www.qualityforum.org/projects/care_coordination.aspx, Accessed April 24, 2012.

McDonald K, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas. Vol No. 11-0023-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/careatlas/. Accessed April 24, 2012.

Saultz JW. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:134–143.

Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977;15:347–349.

Jee SH, Cabana MD. Indices for continuity of care: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:158–188.

Barnett ML, Landon BE, O'Malley AJ, Keating NL, Christakis NA. Mapping physician networks with self-reported and administrative data. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1592–1609.

Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Ann Rev Pub Health. 2007;28:69–93.

Wasserman S, Faust K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Ann Rev Sociol. 2008;34:405–429.

2010 National Healthcare Quality Report. 2010; http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr10.htm. Accessed April 24, 2012.

The Johns Hopkins ACG System Reference Manual Version 9.0. 2009; www.acg.jhsph.org. Accessed April 24, 2012.

Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Paper presented at: International Conference on Complex Systems 2006; Boston, MA.

Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29:452–472.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502.

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. Br Med J. 2003;327:1219–1221.

Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:247–258.

O'Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:56–65.

Chen AH, Kushel MB, Grumbach K, Yee HF. A safety-net systems gains efficiencies through 'eReferrals' to specialists. Health Aff. 2010;29:969–971.

Kim Y, Chen AH, Keith E, Yee HF, Kushel MB. Not perfect, but better: primary care providers' experiences with electronic referrals in a safety net health system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:614–619.

Pham HH, O'Malley AS, Bach PB, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians' links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(4):236–242.

Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130–1139.

Bynum JPW, Bernal-Delgado E, Gottlieb D, Fisher E. Assigning ambulatory patients and their physicians to hospitals: a method for obtaining population-based provider performance measurements. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:45–62.

Liebhaber A, Grossman JM. Physicians Moving to Mid-Sized, Single-Specialty Practices. Tracking Report No.18. 2007. http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/941/941.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2012.

Singer SJ, Burgers J, Friedberg M, Rosenthal MB, Leape L, Schneider E. Defining and measuring integrated patient care: promoting the next frontier in health care delivery. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68:112–127.

Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:666–674.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors thank Donniell Fishkind for his careful review of the manuscript. He did not receive compensation for his effort.

Funders

Dr. Pollack’s salary was supported by a career development award from the NIH National Cancer Institute and Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (1K07CA151910-01A1). The funders had no role in the design and conduct off the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

This work was performed with support by faculty and staff at The Johns Hopkins University, where the ACG method was developed and is maintained. The Johns Hopkins University holds the copyright to the ACG software. To help support research and development, The Johns Hopkins University receives royalties from health plans and other organizations that use the ACG software. The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pollack, C.E., Weissman, G.E., Lemke, K.W. et al. Patient Sharing Among Physicians and Costs of Care: A Network Analytic Approach to Care Coordination Using Claims Data. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 459–465 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2104-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2104-7