Abstract

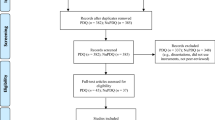

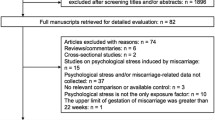

Mounting evidence from clinic and convenience samples suggests that stress is an important predictor of adverse obstetric outcomes. Using a proposed theoretical framework, this review identified and synthesized the population-based literature on the measurement of stress prior to and during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes. Population-based, peer-reviewed empirical articles that examined stress prior to or during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes were identified in the PubMed and PsycInfo databases. Articles were evaluated to determine the domain(s) of stress (environmental, psychological, and/or biological), period(s) of stress (preconception and/or pregnancy), and strength of the association between stress and obstetric outcomes. Thirteen studies were evaluated. The identified studies were all conducted in developed countries. The majority of studies examined stress only during pregnancy (n = 10); three examined stress during both the preconception and pregnancy periods (n = 3). Most studies examined the environmental domain (e.g. life events) only (n = 9), two studies examined the psychological domain only, and two studies examined both. No study incorporated a biological measure of stress. Environmental stressors before and during pregnancy were associated with worse obstetric outcomes, although some conflicting findings exist. Few population-based studies have examined stress before or during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes. Although considerable variation exists in the measurement of stress across studies, environmental stress increased the risk for poor obstetric outcomes. Additional work using a lifecourse approach is needed to fill the existing gaps in the literature and to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which stress impacts obstetric outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Heron, M. (2012). Deaths: Leading causes for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Vohr, B. R., Wright, L. L., Dusick, A. M., et al. (2000). Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics, 105, 1216–1226.

Bhutta, A. T., Cleves, M. A., Casey, P. H., et al. (2002). Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 288, 728–737.

Arck, P. C., Rucke, M., Rose, M., et al. (2008). Early risk factors for miscarriage: a prospective cohort study in pregnant women. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 17, 101–113.

Dole, N., Savitz, D. A., Hertz-Picciotto, I., et al. (2003). Maternal stress and preterm birth. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 14–24.

Copper, R. L., Goldenberg, R. L., Das, A., et al. (1996). The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 175, 1286–1292.

Gennaro, S., & Hennessy, M. D. (2003). Psychological and physiological stress: Impact on preterm birth. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 32, 668–675.

Nordentoft, M., Lou, H. C., Hansen, D., et al. (1996). Intrauterine growth retardation and premature delivery: The influence of maternal smoking and psychosocial factors. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 347–354.

Paarlberg, K. M., Vingerhoets, J., Passchier, J., et al. (1999). Psychosocial predictors of low birthweight: A prospective study. BJOG, 106, 834–841.

Pagel, M. D., Smilkstein, G., Regen, H., et al. (1990). Psychosocial influences on new born outcomes: A controlled prospective study. Social Science and Medicine, 30, 597–604.

Pritchard, C., & Teo Mfphm, P. (1994). Preterm birth, low birthweight and the stressfulness of the household role for pregnant women. Social Science and Medicine, 38, 89–96.

Rondo, P., Ferreira, R., Nogueira, F., et al. (2003). Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57, 266–272.

Jacobsen, G., Schei, B., & Hoffman, H. (1997). Psychosocial factors and small-for-gestational-age infants among parous Scandinavian women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. Supplement, 165, 14–18.

Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. In S. Cohen, R. C. Kessler, & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists (p. 3). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lu, M., & Halfon, N. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7, 13–30.

Dunkel-Schetter, C., & Glynn, L. (2010). Stress in pregnancy: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues to guide interdisciplinary research. In: R. Contrada & A. Baum (Eds.), Handbook of stress science. New York: Springer.

Misra, D., Guyer, B., & Allston, A. (2003). Integrated perinatal health framework. A multiple determinants model with a life span approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 65–75.

Halfon, N., & Hochstein, M. (2002). Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly, 80, 433–479.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

House, J. S. (1974). Occupational stress and coronary heart disease: A review and theoretical integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 15, 12–27.

Evans, R. G., & Stoddart, G. L. (1990). Producing health, consuming health care. Social Science and Medicine, 31, 1347–1363.

Witt, W. P., Wisk, L. E., Cheng, E. R., et al. (2011). Preconception mental health predicts pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes: A national population-based study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 1525–1541.

Harville, E., Xiong, X., & Buekens, P. (2010). Disasters and perinatal health: A systematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 65, 713–728.

Witt, W. P., Wisk, L. E., Cheng, E. R., et al. (2011). Poor prepregnancy and antepartum mental health predicts postpartum mental health problems among US women: A nationally representative population-based study. Women’s Health Issues, 21, 304–313.

Federenko, I., & Wadhwa, P. (2004). Women’s mental health during pregnancy influences fetal and infant developmental and health outcomes. CNS Spectrums, 9, 198–206.

Metcalfe, A., Lail, P., Ghali, W. A., et al. (2011). The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 25, 236–245.

Blaxter, M. (2010). Health (key concepts). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Szklo, M. (1998). Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiologic Reviews, 20, 81–90.

Khashan, A. S., McNamee, R., Abel, K. M., et al. (2009). Rates of preterm birth following antenatal maternal exposure to severe life events: A population-based cohort study. Human Reproduction, 24, 429–437.

Khashan, A. S., McNamee, R., Abel, K. M., et al. (2008). Reduced infant birthweight consequent upon maternal exposure to severe life events. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 688–694.

Precht, D. H., Andersen, P. K., & Olsen, J. (2007). Severe life events and impaired fetal growth: A nation-wide study with complete follow-up. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 86, 266–275.

Lu, M., & Chen, B. (2004). Racial and ethnic disparities in preterm birth: The role of stressful life events. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191, 691–699.

Nkansah-Amankra, S., Luchok, K. J., Hussey, J. R., et al. (2010). Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000–2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14, 215–226.

Whitehead, N., Hill, H., Brogan, D., et al. (2002). Exploration of threshold analysis in the relation between stressful life events and preterm delivery. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155, 117–124.

Class, Q., Lichtenstein, P., Långström, N., et al. (2011). Timing of prenatal maternal exposure to severe life events and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population study of 2.6 million pregnancies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73, 234–241.

Eskenazi, B., Marks, A., Catalano, R., et al. (2007). Low birthweight in New York City and upstate New York following the events of September 11th. Human Reproduction, 22, 3013–3020.

Zhu, J. L., Hjollund, N. H., Andersen, A. M., et al. (2004). Shift work, job stress, and late fetal loss: The national birth cohort in Denmark. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 46, 1144–1149.

Pryor, J., Thompson, J., Robinson, E., et al. (2003). Stress and lack of social support as risk factors for small-for-gestational-age birth. Acta Paediatrica, 92, 62–64.

Ghosh, J. K., Wilhelm, M. H., Dunkel-Schetter, C., et al. (2010). Paternal support and preterm birth, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a study in Los Angeles county mothers. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 13, 327–338.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Tegethoff, M., Greene, N., Olsen, J., et al. (2010). Maternal psychosocial adversity during pregnancy is associated with length of gestation and offspring size at birth: Evidence from a population-based cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 419–426.

Sable, M., & Wilkinson, D. (2000). Impact of perceived stress, major life events and pregnancy attitudes on low birth weight. Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 288–294.

Atrash, H. K., Johnson, K., Adams, M., et al. (2006). Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: The time to act. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10, S3–S11.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. M. (1987). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–49). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840, 33–44.

McDade, T. W., Williams, S., & Snodgrass, J. J. (2007). What a drop can do: dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography, 44, 899–925.

Affonso, D. D., Liu-Chiang, C. Y., & Mayberry, L. J. (1999). Worry: Conceptual dimensions and relevance to childbearing women. Health Care for Women International, 20, 227–236.

Lobel, M., Cannella, D. L., Graham, J. E., et al. (2008). Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology, 27, 604–615.

Misra, D., O’Campo, P., & Strobino, D. (2001). Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 15, 110–122.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (Contract Nos HHSN275200503396C and HHSN275201100014C, National Children’s Study Wisconsin Study Center (PI: M. Durkin and S. Leuthner). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Additional funding for this research was provided by a grant from the Health Disparities Research Scholars Program (FW; T32 HD049302; PI: G. Sarto). We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Witt, W.P., Litzelman, K., Cheng, E.R. et al. Measuring Stress Before and During Pregnancy: A Review of Population-Based Studies of Obstetric Outcomes. Matern Child Health J 18, 52–63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1233-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1233-x