Abstract

After stem cell transplantation, human patients are prone to life-threatening opportunistic infections with a plethora of microorganisms. We report a retrospective study on 116 patients (98 children, 18 adults) who were transplanted in a pediatric bone marrow transplantation unit. Blood, urine and stool samples were collected and monitored for adenovirus (AdV) DNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time PCR (RT-PCR) on a regular basis. AdV DNA was detected in 52 (44.8%) patients, with mortality reaching 19% in this subgroup. Variables associated with adenovirus infection were transplantations from matched unrelated donors and older age of the recipient. An increased seasonal occurrence of adenoviral infections was observed in autumn and winter. Analysis of immune reconstitution showed a higher incidence of AdV infections during periods of low T-lymphocyte count. This study also showed a strong interaction between co-infections of AdV and BK polyomavirus in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The immune reconstitution period following hematopoietic stem cell transplantations (HSCT) is accompanied by a high incidence of viral infection due to profound immunodeficiency. Adenoviral infections have been increasingly recognized as a clinical problem, and their significance needs to be elucidated. There are 52 currently known serotypes of human adenoviruses (AdV) [17, 33], which have been regarded as life-threatening pathogens after bone marrow transplantation [7, 9, 16, 31]. They are commonly detected in stool and pharyngeal swabs of healthy individuals, causing self-limiting infections of the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal system, and occasionally, the eye or urinary tract [1, 3, 7, 10, 12, 16]. In transplant recipients, AdV may occur as a de novo infection or reactivation of latent virus after primary infection in childhood [10]. According to different studies, the estimated rate of AdV infection after HSCT ranges from 3–47% [2, 3, 6, 10, 11, 13, 20–22, 27, 30], with mortality from 10 to 80% [10, 12, 16, 27, 28, 30]. A higher morbidity risk is present in recipients when the transplant is received from matched unrelated donors (MUDs) or partially matched family donors (PMFDs), after ex vivo T cell depletion, at younger age, in the presence of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), after antithymocyte globulin therapy and in cases of severe lymphopenia at the time of first detection of the virus [1–6, 15, 19, 20, 26, 28, 30]. Lack of efficient anti-AdV prophylaxis [3, 13, 16, 19, 20, 26] demands rapid and sensitive detection of human adenoviruses in clinical practice [26]. In this study, we report the results of a retrospective trial including 116 stem cell transplant recipients. Molecular techniques based on polymerase chain reaction and specific real-time PCR were used to detect AdV.

Materials and methods

Definitions

Adenoviral infection was defined as the presence of AdV DNA in the clinical sample obtained from whole blood, plasma, urine or stool, detected by PCR or RT-PCR, irrespective of symptoms. In contrast, an active infection was defined as the presence of AdV DNA in plasma or detection of an increasing AdV copy number in clinical materials such as whole blood, urine and stool. Disseminated disease was defined by AdV detection in at least two different clinical materials at the same time. Local infection was limited to detection of AdV genome at one body site. Acute GvHD was graded as grades 0 to IV according to standard criteria [29]. Mild acute GvHD was defined as grades I–II, and severe, as III–IV.

Patients and clinical samples

This retrospective study included 116 patients undergoing HSCT at the local Department of Paediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation, between 2007 and 2009. All recipients were tested for AdV infection on a regular basis after transplantation. The characteristics of the recipients are shown in Table 1. Due to the high variability of treated patients, different conditioning regimens were used (Table 2). Ex vivo T cell depletion of the graft was performed in all haploidentical transplantations (n = 9). Clinical samples of whole blood, plasma, urine and stool were collected. Virological surveillance was performed regularly every 1–2 weeks, starting from the day of transplantation (Day 0) and continued until discharge of the patient, and once a month afterwards. Parallel to this, a weekly flow cytometric assessment of lymphocyte (CD3+) count in peripheral blood samples was performed.

Control virus strains

Six control virus strains of different serotypes, representing species (A–F), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA). DNA isolated from control virus strains was used for standard curve preparation. It also served as a target DNA for positive controls for detection of inhibition in PCR and RT-PCR.

Preparation and extraction of clinical samples

DNA from whole-blood samples (EDTA) was extracted immediately after collection. Urine and stool were collected into sterile, disposable containers. Stool samples were frozen (−20°C) immediately after collection and transported on ice to the laboratory. The samples of plasma (EDTA) and urine were centrifuged at 3,000×g for 20 min and 3,000×g for 10 min, respectively, before freezing at −20°C. DNA was extracted from whole blood and plasma using spin columns from the QIAamp Blood Mini Kit, from urine, using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, and from stool, using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In largely cell-free fluids, RNA carrier was used. From a starting amount of 200 μl of whole blood or plasma, 140 μl of urine and 200 mg of stool, 50 μl of extracted DNA was collected. Six microliters of DNA-containing extract was used in standard PCR and 7 μl was used in real-time PCR amplification.

Preparation and extraction of control viral DNA

Viral genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μl of viral lysate, using a QIAamp Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The control PCR product used for preparation of the standard curve was purified by using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany).

Standards and calibration curve generation

For quantification of virus load, two external standard curves were applied: one for evaluation of adenoviruses from AdV species A, C, F and the second for quantification of viruses from AdV species B, D and E. Preparation of the standard curves was based on serial dilutions of fluorometrically quantified in-home cloned plasmid standards or an amplicon quantitative standard prepared using primers specific for AdV type 5. Plasmid or amplicon concentration and purity were determined using a NanoPhotometer (Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany). The viral copy number was calculated based on the known molecular weight of the plasmid and amplicon.

Polymerase chain reaction

The screening examination of all clinical samples was performed as a singleplex PCR assay in a 20-μl volume containing 10 μl HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit (QIAagen GmbH, Germany), 1 μl of forward and reverse primers (0.5 μM final conc.) ADV1 5′-GCC GAG AAG GGC GTG CGC AGG TA-3′ and ADV2 5′-ATG ACT TTT GAG GTG GAT CCC ATG GA-3′ (TIB MOLBIOL, Poland), which were described previously [24], 2 μl of distilled water and 6 μl of target viral nucleic acid. Reference strains of adenoviruses were used as positive controls in each run; distilled water instead of template was used as a negative control. On a basis of fluorometrically quantified viral DNA, we concluded that it was possible to reliably detect 7.5 × 101 copies of viral DNA per ml of the sample by classical PCR. Positive samples were quantified by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) to determine virus load.

RT-PCR

Viral copy numbers were quantified using a real-time PCR that was developed in our laboratory, based on specific primers and probes described elsewhere [7]. Quantitative amplification was performed on Real Time 7500 PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) in 96-well format by using TaqMan-based chemistry. In brief, the optimized master mix for the ACF reaction consisted of 13 μl of 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA), 1 μl of each primer (160 nM final conc.), except second reverse (320 nM final conc.), 1 μl of each probe (80 nM final conc.), 2.6 μl IC Master Mix, 0.52 μl of water, and 7 μl of target DNA solution in final total volume of 32 μl. The reaction for BDE serotypes consisted of: 12 μl of 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA), 1 μl of 2 primers (160 nM final conc.), 1 μl of each probe (80 nM final conc.), 2.4 μl IC MasterMix, 0.6 μl of water and 7 μl of extracted DNA in a total volume of 26 μl. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 min for AmpErase UNG activation, then 95°C for 10 min for denaturation, followed by 55 cycles (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min). TaqMan Exogenous Internal Positive Control (VIC-probe) from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, USA) was added during the DNA extraction step (5 μl/200 μl of lysate) and was coamplified in the multiplex reaction. To reduce the risk of sample contamination, the AmpErase system was used. Each run included at least two no-template controls and three different positive controls. The lower detection limit was determined by the analysis of dilution series, created using fluorometrically quantified DNA of AdV5 (as representative for ACF reaction) and DNA of AdV21 (as representative of AdV for BDE reaction). The sensitivity was demonstrated to be 2.5 (for multiplex reaction detecting viruses from species A, C, F) and 24 (for multiplex reaction detecting viruses from species B, D, E) copies of viral genome/reaction.

Additional methods

Evaluation of blood counts of CD3+ T cells was performed on a Cytomics 7500 (Beckman Coulter, USA) flow-cytometer using anti-CD3+-FITC (BD, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions. An Alert Q-PCR BKV Kit was used for evaluation of BKV infection.

Therapy

In patients with identified AdV replication and disseminated infection, therapy with cidofovir (CDV) was instituted. Cidofovir was administered with adequate hydration at a dose of 5 mg per kg BW with probenecid 2 h before and 3 and 8 h after CDV infusion. Therapy was continued at weekly intervals until clearance of AdV-DNA was achieved. Patients treated for AdV infection received 2–10 doses (median, four doses) of cidofovir.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica v.8.0 (StatSoft, Kraków, Poland). The chi square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for a univariate analysis of risk. To evaluate multiple risk factors for infection, a logistic regression model was used. An incidence of AdV-related death among the AdV-infected patients was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method and compared with log-rank and Cox–Mantel tests. The immunological status, based on the CD3+ cell count, was used to categorize patients into four groups (<500, <1,000, <2,000 and <6,500/μl), and its impact on adenoviral infection was determined using correspondence analysis and the Cochran–Cox test. Mean copy numbers of AdV in MUD, MMREL and IDSIB recipients were compared using ANOVA. The AdV dependence of concomitant infections was evaluated by Mann–Whitney test.

Results

Incidence of adenovirus infection and risk factors

Adenoviral infection was detected in 52 (44.8%) of 116 transplant recipients. No infections occurred in autograft recipients. The median age of AdV-infected patients at the time of HSCT was 9.5 years (range 1.0–44.0), with 36 male and 16 female patients. Morbidity was uniformly distributed among different periods after transplantation: 20% (0–3 weeks after HSCT), 21% (3–6 weeks), 17% (6–9 weeks), 18% (9–15 weeks) and 24% (>15 weeks) (p > 0.05). Of 52 infected patients, 10 died (8 MUD and 2 MSD) at a mean time of 98.4 days (range 11–245) after transplantation. GvHD was diagnosed in 7 of 10 (70%) patients who succumbed after HSCT: 4 GvHD I–II and 3 GvHD IV. GvHD was observed in 24 of 42 patients who survived, but 18/24 (75%) of them developed GvHD I–II, and 6/24 (25%) developed GvHD III–IV (p = 0.44). There was only one patient with GvHD IV in the group of infected patients who survived (p = 0.003). The probability of survival was 0.76 in the case of AdV-infected patients, whereas the probability was 0.64 in the case of AdV-free patients, but this difference was not significant (p = 0.26) (Fig. 1a). Analyzing factors affecting survival of the AdV cohort, the patient’s age was significant (p = 0.006). The probability of survival for 200 days after HSCT decreased with older age, 1–7 years (0.85), 8–14 years (0.76), 15–21 years (0.63), and reached a minimum in the age group 22–28 (0.46) (Fig. 1b).

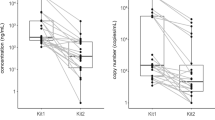

The most common sites of AdV-DNA isolation were stool 12/24 (50%) and urine 56/116 (48.3%), followed by whole blood 30/116 (25.9%) and plasma 22/116 (18.9 %). The median time from transplantation to the first AdV-positive result from urine was 17 days after HSCT (range 7–59) and 38 days in whole blood (range 7–183). In 3 patients, we were able to detect AdV-DNA as early as on Day 7 in urine or whole blood samples. This might indicate the necessity for AdV monitoring to start by at least Day 7 after transplantation. Blood positivity for AdV-DNA preceded plasma positivity on average by 2 days. Nineteen out of 52 patients developed disseminated infection: plasma and urine (28.8%), urine and stool (7.7%). The viral load in cases of disseminated disease did not exceed 104 copies/ml or gram of the sample (Fig. 2). Medium concentrations were as follows: 4.7 × 103 copies/ml in urine, 3.4 × 104 copies/ml in plasma, and 2.3 × 103 copies/g in stool. In 33/52 (63.5%) infected patients, local AdV infection was found in urine 29/52 (55.8%), plasma 1/52 (1.9%) or stool 3/52 (5.8%). Median concentration: urine, 7.4 × 102 copies/ml; plasma, 8.3 × 103 copies/ml; and stool, 5.6 × 102 copies/ml.

Among patients with local infection, 5 of 33 (15.2%) died. Disseminated disease, surprisingly, was not associated with higher mortality (p = 0.63) in comparison to patients with local infection. Mortality among patients with disseminated disease was 5/19 (26.3%). Adenoviruses were more frequently isolated from the blood and urinary tract of recipients of grafts from unrelated donors (MUD) (19%) than mismatched related (MMREL) (8%) or sibling (IDSIB) (10%) donors (p = 0.004). The mean copy numbers are listed in Table 3.

On univariate analysis, the AdV infection rate was correlated with older age of the patient (p = 0.005), and among children, the highest morbidity was observed between 7 to 12 years. T cell-depleted transplantations made up only 7.8% of all transplantations (9/116). According to the results from our study group, depletion of T cells from the graft material did not make patients more prone to adenoviral infections. Adenoviral DNA was found in blood (27/107), plasma (20/107) and urine (48/107) from patients undergoing non-T-depleted transplantations and in blood (3/9), plasma (2/9) and urine (2/9) of T cell depleted transplantations (p > 0.05). The use of anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and total body irradiation (TBI) in conditioning regimens had no influence on virus appearance, 39/81 versus 15/35 and 16/32 versus 38/84, respectively, p > 0.05. This confirms the suggestion that prevention of graft rejection by anti-thymocyte globulin and TBI does not conduce adenoviral infections as much as was thought previously. Seasonal fluctuations of adenoviral infection were observed. The incidence of AdV infections in each season was as follows: spring 11/45 (24.4%), summer 9/19 (47.4%), autumn 13/25 (52%) and winter 19/27 (70.4%) (p = 0.001) (Fig. 3).

No significant differences in AdV morbidity between peripheral blood (41/89) and bone marrow recipients (13/25) (p > 0.05) were observed. The gender of the recipient or donor was not associated with greater incidence of AdV infection (p > 0.05), female 43 versus male 48%. The incidence rates of AdV infections were similar according to primary disease; patients with malignant and non-malignant disorders had virtually identical morbidity (46 vs. 47%, p = 0.88).

Adenovirus infection and immune reconstruction

Analysis by median comparison showed that the median number of CD3+ cells in AdV-infected patients (median 490/μl, range 0–3,309/μl) was lower than among AdV-free recipients (median 665/μl, range 0–6,476/μl), p = 0.04. Correspondence analysis confirmed that AdV-free samples correlated with higher CD3+ cells counts (1,000–6,400/μl) (Fig. 4).

BK polyomavirus co-infections

Seven hundred fifty-two plasma and 705 urine samples were tested for concomitant infections with BK polyomavirus. Some patients presented co-infections after infection with one viral agent; therefore, examination of clinical materials was the basis of segregation. DNA of both AdV and BKV was detected in 39 plasma and 111 urine samples. One hundred seventeen plasma samples and 276 urine samples were positive for BK polyomavirus only, whereas 43 plasma and 58 urine samples contained AdV-DNA only. Co-occurrence of AdV and BKV both in plasma (p < 0.001) and in urine (p = 0.001) was statistically significant. Analysis using the Chi square test suggested that the presence of one virus was conductive to the occurrence of a concomitant virus. Examination of multiple risk factors (logistic regression) confirmed that BKV infection and transplantation from MUD increase the risk of AdV infection (p < 0.001 and p = 0.013, respectively). Correspondence analysis showed that, in most cases, both AdV and BKV are present together or both are absent. Wald–Wolfowitz and Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare mean viral loads of both viruses in co-infections. Viral copy numbers were different in plasma (p < 0.001) and urine (p = 0.02). The AdV load was higher in plasma (mean 5.8 × 103 copies/ml) and urine (mean 1.1 × 102 copies/ml) in co-infected samples than in the samples without BKV: plasma (mean 9.2 × 101 copies/ml), urine (mean 6.6 × 101 copies/ml). This confirms that infection with one virus type facilitates replication of the other virus. We also confirmed that the total number of CD3+ cells in peripheral blood in patients with AdV/BKV co-infections in plasma was significantly lower (352 ± 747 cells/μl) than in those with only AdV infection (434 ± 491 cells/μl) (p = 0.037). We could not confirm this observation for co-infections in urine. Multivariate analysis with logistic regression revealed that BKV infection and unrelated graft recipients played a role in the development of AdV infection (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our results show that adenoviral infections are very common in recipients undergoing HSCT. Previous studies indicated a moderate frequency of adenovirus infections in allogeneic SCT [3, 6, 22] associated with significant mortality [10]. This study demonstrated a high proportion (44.8%) of AdV-infected recipients, with a mortality risk of 19.2% (10/52). Our data, like those published by Walls et al. [31], Ison [16] and Myers et al. [25] show a higher incidence of adenoviral infection than data reported before the year 2003 by others [2, 3, 6, 10, 22, 28]. Therefore, we believe that the greater incidence of AdV infections in our study group might be a result of more sensitive methods used for AdV detection. We also need to mention the high proportion of AdV-positive stool samples and the low threshold for positivity in our research, which might also have an influence on the greater proportion of positive results. Our group consisted predominantly of MUD transplantation recipients (65.5%), who are more susceptible to AdV infections [30]. Moreover, due to application of molecular methods, we achieved very high sensitivity in the analysis of large-volume body fluid samples.

It has been suggested that there is a higher incidence of infection in children compared to adults [1, 2, 21, 22, 30]. Data reported by Chakrabarti et al. [6] pointed to a lack of dependence between age and infection. In our cohort, older age was associated with a greater incidence of AdV infection (p < 0.05). The proportion of MUD HSCT in children (62/98, 63.2%) was similar to that of the adult group (14/18, 77.7%). The highest incidence in the medium age group of children may be the result of possible enhanced replication of latent virus, because over 80% of children are infected by adenoviruses by age 6 [10]. Persistent infections are predominantly caused by AdV from species C. The AdV serotypes from species C are also the most common infections in childhood.

Examined risk factors for adenoviral infections included the recipient’s sex and underlying disease. The role of such factors was not observed in our study, in contrast to other publications [5, 6, 30]. Previous studies also usually documented the onset of adenovirus infection during the first 100 days after transplantation [6, 20, 28]. Our study has shown no difference between the early and late period after HSCT.

Interestingly, we detected an increased seasonal incidence of adenoviral infections in winter and autumn. This is consistent with AdV morbidity in healthy individuals, suggesting the importance of airborne and droplet transmission of the virus. Because of this, more attention should be paid to limiting visitor access to the patients.

In 36.5% of AdV patients, disseminated infection was found, but the prognosis for these patients was not worse than for those with localized disease. The presence of disseminated disease was not associated with higher mortality, even with a high viral load in plasma. Similar observations were made by other investigators, which may be attributed to rapid institution of cidofovir therapy in patients with identified dissemination of infection [6, 14, 28, 32].

The most common site of AdV isolation was stool, followed by urine, then whole blood and plasma. This is similar to the results of Baldwin et al. [2] and consistent with healthy patients developing enteritis and upper respiratory tract infections [8]. We investigated testing of whole blood samples. Excluding the cases of latency in lymphocytes of whole blood (defined as AdV-DNA presence only in whole-blood samples without an increase of viral load in whole blood and without the presence of virus in plasma or other tested materials at the same time), we noticed that AdV DNA was detected in blood at least 2 days before an active infection. Hence, monitoring of peripheral blood samples may have predictive value in surveillance of infection development.

We showed that the use of anti-thymocyte globulin and total body irradiation in the conditioning regimen did not increase the risk of AdV infection in stem cell transplantation recipients. The majority of the patients tested received stem cells from peripheral blood (89/116), and there was no difference in AdV morbidity between peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) and bone marrow (BM) recipients. Our study showed that recipients of unmanipulated graft material are not more likely to develop AdV infections, so a larger number of donor lymphocytes is probably not associated with greater transmission of latent AdV. The role of donor lymphocytes in the transmission of viruses from donor to recipient still needs to be elucidated.

Graft recipients are generally more susceptible to infections during post transplant recovery [25].

In concordance with some studies [16, 27], in our study, 3 of 7 patients who died after transplantation developed acute grade IV GvHD (p = 0.003). This may suggest a strong correlation between GvHD and the patient’s survival. GvHD requires immunosuppressive therapy, which lowers the number of lymphocytes and hampers the immunity of the recipient, thus enabling adenoviral infections. A low lymphocyte count due to immunosuppressive treatment or delayed T cell reconstitution was an important predictor for detection of adenoviral infections in our study, which is consistent with earlier observations [5, 6]. An inadequate humoral response due to B lymphocyte impairment can also contribute to AdV infection susceptibility [11].

Multiple plasma and urine samples were positive for both AdV and BKV. The CD3+ cell number in AdV/BKV co-infected patients was also lower than in those with isolated AdV infection. The occurrence of BK polyomavirus might intensify replication of AdV, because the AdV load was significantly higher in co-infection than in samples with AdV infection alone. Therefore, greater immunodeficiency may promote infections with more than one viral agent, and a low lymphocyte count in peripheral blood due to delayed immune recovery may facilitate the replication of AdV. This mechanism may not be sufficient to explain viral co-infections in all transplant recipients, because we identified cases that were asymptomatic and diagnosed in a state of relative immunocompetence. From a molecular point of view, the presence of co-infections may also be a result of interactions between cohabitating viruses due to transactivation of gene expression of other viruses. There are known examples of viral regulatory proteins that transactivate promoter sequences of heterologous viruses. Polyomavirus T antigen increases expression from the adenovirus E2 promoter, and this transactivation is as efficient as the homologous viral protein ElA [23]. Kristoffersen et al. [18] reported that BK large T antigen enhanced the expression of human CMV IE genes through heterologous transcriptional transactivation of the CMV major IE promoter in A549 cells. On this basis, it may be concluded that adenoviral transcription factors regulating specific target promoters can be induced by different viral regulatory proteins, like those of polyomaviruses. The reason for the higher AdV load in urine samples with concomitant BK polyomavirus infection is still unclear and needs to be determined in a broader examination. It is a noteworthy observation that patients can be afflicted by multiple viral infections, which might originally result from the prevalence of common risk factors, although one needs to consider the reciprocal enhancement of viral infections.

Our research confirms that adenovirus viremia is not always associated with fatal outcome. This clinical effect might be explained by the high efficacy of aggressive cidofovir therapy in patients with disseminated disease, even without symptomatic disease. The crucial factor in AdV therapy appears to be prompt detection and early initiation of appropriate anti-viral therapy in high-risk patients.

References

Bachanova V, Brunstein CG, Burns LJ, Miller JS, Luo X, Defor T Young JA, Weisdorf DJ, Tomblyn M (2009) Fewer infections and lower infection-related mortality following non-myeloablative versus myeloablative conditioning for allotransplantation of patient with lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant 43:237–244

Baldwin A, Kingman H, Darville M, Foot AB, Grier D, Cornish JM, Goulden N, Oakhill A, Pamphilon DH, Steward CG, Marks DI (2000) Outcome and clinical course of 100 patients with adenovirus infection following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 26:1333–1338

Bruno B, Gooley T, Hackman RC, Davis C, Corey L, Boeckh M (2003) Adenovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: effect of ganciclovir and impact on survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 9:341–352

Chakrabarti S, Collingham KE, Fegan CD, Milligan DW (1999) Fulminant adenovirus hepatitis following unrelated bone marrow transplantation: failure of intravenous ribavirin therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant 23:1209–1211

Chakrabarti S, Collingham KE, Fegan CD, Pillay D, Milligan DW (2000) Adenovirus infections following haematopoietic cell transplantation: is there a role for adoptive immunotherapy? Bone Marrow Transplant 26:305–307

Chakrabarti S, Mautner V, Osman H, Collingham KE, Fegan CD, Klapper PE, Moss PA, Milligan DW (2002) Adenovirus infections following allogeneic stem cell transplantation: incidence and outcome in relation to graft manipulation, immunosuppression, and immune recovery. Blood 100:1619–1627

Ebner K, Suda M, Watzinger F, Lion T (2005) Molecular detection and quantitative analysis of the entire spectrum of human adenoviruses by two-reaction real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 43:3049–3053

Echavarria M (2008) Adenoviruses in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:704–715

Fujita Y, Rooney CM, Heslop HE (2008) Adoptive cellular immunotherapy for viral diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant 41:193–198

Hale GA, Heslop HE, Krance RA, Brenner MA, Jayawardene D, Srivastava DK, Patrick CC (1999) Adenovirus infection after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 23:277–282

Heemskerk B, Lankester AC, van Vreeswijk T, Beersma MF, Claas EC, Veltrop-Duits LA, Kroes AC, Vossen JM, Schilham MW, van Tol MJ (2005) Immune reconstitution and clearance of human adenovirus viremia in pediatric stem-cell recipients. J Infect Dis 191:520–530

Hierholzer JC (1992) Adenoviruses in the immunocompromised host. Clin Microbiol Rev 5:262–274

Hoffman JA, Shah AJ, Ross LA, Kapoor N (2001) Adenoviral infections and a prospective trial of cidofovir in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 7:388–394

Howard DS, Phillips GL II, Reece DE, Munn RK, Henslee-Downey J, Pittard M, Barker M, Pomeroy C (1999) Adenovirus infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 29:1494–1501

Hromas R, Cornetta K, Srour E, Blanke C, Broun ER (1994) Donor leukocyte infusion as therapy of life-threatening adenoviral infections after T cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation. Blood 84:1689–1690

Ison MG (2006) Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 43:331–339

Jones MS 2nd, Harrach B, Ganac RD, Gozum MM, Dela Cruz WP, Riedel B, Pan C, Delwart EL, Schnurr DP (2007) New adenovirus species found in a patient presenting with gastroenteritis. J Virol 8:5978–5984

Kristoffersen AK, Johnsen JI, Seternes OM, Rollag H, Degre′ M, Traavik T (1997) The human polyomavirus BK T antigen induces gene expression in human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res 52:61–71

Lankester AC, Heemskerk B, Class EC, Schilham MW, Beersma MF, Bredius RG, van Tol MJ, Kroes AC (2004) Effect of ribavirin on the plasma viral DNA load in patients with disseminating adenovirus infection. Clin Infect Dis 38:1521–1525

La Rosa AM, Champlin RE, Mirza N, Gajewski J, Giralt S, Rolston KV, Raad I, Jacobson K, Kontoyiannis D, Elting L, Whimbey E (2001) Adenovirus infections in adult recipients of blood and marrow transplants. Clin Infect Dis 32:871–876

Leen AM, Bollard CM, Myers GD, Rooney CM (2006) Adenoviral infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Bone Marrow Transplant 12:243–251

Lion T, Baumgartinger R, Watzinger F, Matthes-Martin S, Suda M, Preuner S, Futterknecht B, Lawitschka A, Peters C, Potschger U, Gadner H (2003) Molecular monitoring of adenovirus in peripheral blood after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation permits early diagnosis of disseminated disease. Blood 102:1114–1120

Loeken MR, Khoury G, Brady J (1986) Stimulation of the adenovirus E2 promoter by simian virus 40 T antigen or ElA occurs by different mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 6:2020–2026

McDonough M, Kew O, Hierholzer JC (1993) PCR detection of human adenoviruses. In: Persing DH, Smith TF, Tenover FC, White TJ (eds) Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp 389–393

Myers GD, Krance RA, Weiss H, Kuehnle I, Demmler G, Heslop HE, Bollard CM (2005) Adenovirus infection rates in pediatric recipients of alternate donor allogeneic bone marrow transplants receiving either antithymocyte globulin (ATG) or alemtuzumab (Campath). Bone Marrow Transplant 36:1001–1008

Perlman J, Gibson C, Pounds SB, Gu Z, Bankowski MJ, Hayden RT (2007) Quantitative real-time PCR detection of adenovirus in clinical blood specimens: a comparison of plasma, whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Virol 40:295–300

Robin M, Marque-Juillet S, Scieux C, Peffault de Latour R, Ferry C, Rocha V, Molina JM, Bergeron A, Devergie A, Gluckman E, Ribaud P, Socié G (2007) Disseminated adenovirus infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Haematologica 92:1254–1257

Runde V, Ross S, Trenschel R, Lagemann E, Basu O, Renzing-Köhler K, Schaefer UW, Roggendorf M, Holler E (2001) Adenoviral infection after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT): report on 130 patients from a single SCT unit involved in a prospective multi center surveillance study. Bone Marrow Transplant 28:51–57

Silva MM, Bouzas LFS, Filgueira AL (2005) Tegumentary manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in bone marrow transplantation recipients. An Bras Dermatol 80:69–80

van Tol MJ, Kroes AC, Schinkel J, Dinkelaar W, Claas EC, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Vossen JM (2005) Adenovirus infection in paediatric stem cell transplant recipients: increased risk in young children with delayed immune recovery. Bone Marrow Transplant 36:39–50

Walls T, Hawrami K, Ushiro-Lumb I, Shingadia D, Saha V, Shankar AG (2005) Adenovirus infection after pediatric bone marrow transplantation: is treatment always necessary? Clin Infect Dis 40:1244–1249

Willems L, Lagrange-Xelot M, Gallien S, Robin M, Scieux C, Socié G, Molina JM (2008) Successful outcome of a disseminated adenovirus infection 6 years after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 41:411–412

Xu W, McDonough MC, Erdman DD (2000) Species-specific identification of human adenoviruses by a multiplex PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 38:4114–4120

Acknowledgments

This research project was sponsored by The Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, grant number NN-401-004-536.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bil-Lula, I., Ussowicz, M., Rybka, B. et al. PCR diagnostics and monitoring of adenoviral infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Arch Virol 155, 2007–2015 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-010-0802-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-010-0802-1