Abstract

Purpose

To prospectively report the perimetric defects during a 6-month follow-up (FU) in patients with initially active ocular toxoplasmosis (OT).

Methods

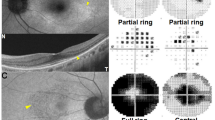

Twenty-four patients were studied, including 11 eyes with chorioretinal toxoplasmosis proven with a positive aqueous humor sample and 13 eyes with a biologically unproven, chorioretinal lesion. Automated 24-2 SITA-Standard visual fields were performed at baseline, at the first, and sixth months of FU. A composite clinical severity score was calculated from visual acuity (VA), severity of vitreitis, chorioretinal lesion size, location of the lesion in zone 1, the presence of an initial macular or papillary edema, and long-term scarring. This provided a relative cutoff level of severity. Nine eyes out of the 24 eyes were considered severe (3 unproven and 6 proven OT).

Results

Initial and final visual field parameters (mean deviation [MD] and pattern standard deviation [PSD]) were significantly correlated (r = 0.873; p < 0.001, and r = 0.890; p < 0.001, respectively). During FU, only foveal threshold [FT] was correlated with VA at baseline (r = 0.48; p = 0.01) and at the 6-month FU visit (r = 0.547; p = 0.004). The MD initial predictive value of clinical severity was 0.739 according to the ROC curve. At baseline, severe and nonsevere OT exhibited no significant difference in term of MD (p = 0.06) and PSD (p = 0.1). During the FU, taking into account all the data, MD, PSD, visual function index [VFI], and FT were associated with the severity of toxoplasmosis (p = 0.018, 0.05, 0.016, and 0.02, respectively): the unproven group had a faster recovery of MD during FU (p = 0.05).

Conclusion

Visual field parameters better reflected the chorioretinal destruction related to the toxoplasmosis lesion and the functional repercussions than VA alone. Interestingly, MD at presentation could be a discriminating factor of severity in active OT, and each visual field parameter follow-up could be a support to manage patients with active OT, especially in the severe group.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Montoya J, Liesenfeld O (2004) Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363(9425):1965–1976

Furtado JM, Winthrop KL, Butler NJ et al (2013) Ocular toxoplasmosis I: parasitology, epidemiology and public health: ocular toxoplasmosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 41(1):82–94

Holland GN (2003) Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Am J Ophthalmol 136(6):973–988

Holland GN (2004) Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Am J Ophthalmol 137(1):1–17

Pleyer U, Schlüter D, Mänz M (2014) Ocular toxoplasmosis: recent aspects of pathophysiology and clinical implications. Ophthalmic Res 52(3):116–123

Weiss LM, Dubey JP (2009) Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol 39(8):895–901

Wilder HC (1952) Toxoplasma chorioretinitis in adults. Arch Ophthalmol 48(2):127–136

Dodds EM, Holland GN, Stanford MR et al (2008) Intraocular inflammation associated with ocular toxoplasmosis: relationships at initial examination. Am J Ophthalmol 146(6):856–865.e2

Martin WG, Brown GC, Parrish RK et al (1980) Ocular toxoplasmosis and visual field defects. Am J Ophthalmol 90(1):25–29

Schlaegel TF, Weber JC (1984) The macula in ocular toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 102(5):697–698

Stanford MR (2005) The visual field in toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Br J Ophthalmol 89(7):812–814

Scherrer J, Iliev ME, Halberstadt M et al (2007) Visual function in human ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol 91(2):233–236

Delair E, Latkany P, Noble AG et al (2011) Clinical manifestations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 19(2):91–102

Commodaro AG, Belfort RN, Rizzo LV et al (2009) Ocular toxoplasmosis: an update and review of the literature. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 104(2):345–350

Garweg JG, de Groot-Mijnes JDF, Montoya JG (2011) Diagnostic approach to ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 19(4):255–261

Goldmann H, Witmer R (1954) Antikörper im Kammerwasser. Ophthalmologica 127(4–5):323–330

Fekkar A, Bodaghi B, Touafek F et al (2008) Comparison of immunoblotting, calculation of the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient, and real-time PCR using aqueous humor samples for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 46(6):1965–1967

Villard O, Filisetti D, Roch-Deries F et al (2003) Comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and PCR for diagnosis of Toxoplasmic chorioretinitis. J Clin Microbiol 41(8):3537–3541

Fardeau C, Romand S, Rao NA et al (2002) Diagnosis of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis with atypical clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol 134(2):196–203

Cunningham ET (2011) Proportionate topographic areas of retinal zones 1, 2, and 3 for use in describing infectious retinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 129(11):1507

European Glaucoma Society (ed) (2014) Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma, 4th edn. PubliComm, Savona, p 195

Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature for Reporting Clinical Data (2005) Results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 140(3):509–516

Ouyang Y, Pleyer U, Shao Q et al (2014) Evaluation of cystoid change phenotypes in ocular toxoplasmosis using optical coherence tomography. PLoS One 9(2):e86626

Diniz B, Regatieri AR et al (2011) Evaluation of spectral domain and time domain optical coherence tomography findings in toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Clin Ophthalmol:645–647

Monnet D (2009) Optical coherence tomography in ocular toxoplasmosis. Int J Med Sci:137–138

Smith JR, Cunningham ET (2002) Atypical presentations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 13(6):387–392

Song A, Scott IU, Davis JL et al (2002) Atypical anterior optic neuropathy caused by toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol 133(1):162–164

Mets MB, Holfels E, Boyer KM et al (1997) Eye manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol 123(1):1–16

Maenz M, Schlüter D, Liesenfeld O et al (2014) Ocular toxoplasmosis past, present and new aspects of an old disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 39:77–106

Riemslag FCC, Brinkman CJJ, Lunel HFEV et al (1992) Analysis of the electroretinogram in toxoplasma retinochorioiditis. Doc Ophthalmol 82(1–2):57–63

Acknowledgments

Association for Research and Teaching in Ophthalmology (ARFO, Grenoble, France), DRCI (Grenoble University Hospital).

Other participating investigators:

Guillemot C., MD, Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital, Saint Etienne, France.

Fricker-Hidalgo H., MD, Department of Parasitology, University Hospital, Grenoble, France.

Brenier-Pinchart M.P., MD, Department of Parasitology, University Hospital, Grenoble, France.

Lesoin A., MD, Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital, Grenoble, France and Grenoble Alpes University, Grenoble, F-38041, France.

Funding

This study was funded by grant number IRB 2009-A00877-50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blot, J., Aptel, F., Chumpitazi, B.F.F. et al. Monitoring of visual field over 6 months after active ocular toxoplasmosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 257, 1481–1488 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04313-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04313-2