Abstract

Objective

To assess the use, side effects and discontinuation rates of iron preparations during pregnancy.

Design

Six hundred and twelve randomly selected postpartum women completed a questionnaire on iron supplement use in the second and third trimesters.

Results

Of the 517 women (84.5%) reported using iron supplements, 453 were eligible for the study. The most common preparation was ferrous fumarate (46.8%, P < 0.01), followed by ferrous sulfate (31.8%), ferric polymaltose (12.4%), and ferric bisglycinate (7.3%). Almost half the participants (45%) reported at least one adverse effect, especially constipation (27.4%, P < 0.01), nausea (10.8%). Multivitamin preparations and ferric bisglycinate were associated with the fewest side effects (23.7, 21.2% respectively, P < 0.01), and ferrous fumarate and immediate-release ferrous sulfate with the most (56.3, 53.7% respectively). Eighty-three women discontinued their originally prescribed iron preparation, mainly (89%) due to side effects. Discontinuation rates were lowest for the multivitamin and ferric bisglycinate (10.5, 9.1%, respectively). In most cases, the specific preparation was recommended by the women’s physician (76%).

Conclusion

Ferrous fumarate-containing multivitamin preparations and ferric bisglycinate, although infrequently recommended as the first-line of iron supplementation, may be associated with less side effects and better compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy is a significant worldwide health problem, affecting 22% of pregnant women in industrialized countries and 52% in non-industrialized countries [1]. Iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy is associated with increased maternal as well as fetal morbidity, including prematurity, low birth-weight and perinatal and infant loss [2–4]. Therefore, routine iron supplementation during the second half of pregnancy has been recommended, in the form of either daily [5] or weekly [6, 7] regimens. Others, however, support a selective iron supplementation only for women with iron deficiency anemia, in order to avoid the increased risk of hemoconcentration associated with routine iron supplementation [6, 8]. Unfortunately, compliance to either iron-supplementation programs, especially among pregnant women, is poor, due in part to the side effects associated with these preparations [9–12].

Currently, there are many iron preparations available, containing different types of iron salts, including ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, ferrous gluconate, ferric polymaltose and ferrous bisglycinate. Moreover, the various preparations also differ in pharmacokinetics (e.g. immediate vs. slow release). Although it is well accepted that the side effects of iron are dose-dependent, the influence of the type of iron salt on the rate of side effects is still unclear.

The purpose of this study was to assess the currently available preparations used for iron supplementation during pregnancy in terms of frequency of use, rate of side effects, and discontinuation rate.

Methods

The study sample consisted of 612 women that were randomly selected 1–3 days postpartum during a 3-month period (March to May 2004) in a single tertiary medical center that serves a versatile population of all socioeconomic levels. All were requested to complete an anonymous multiple-choice questionnaire on iron supplementation during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

Only women that used a routine daily supplementation, as recommended by the national health authorities, were included in the study group. Women with gastrointestinal complaints before pregnancy, and women who took more than one type of iron preparation concomitantly were excluded from the study. To control for the dosage-related effects, women who took more than one tablet per day of the specific iron preparation were excluded as well.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. All results are presented as mean ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Statistical significance of the results was determined with chi-square test. A P value of equal to or less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of the 517 (84.5%) women who reported using iron supplements during the second and the third trimesters, 453 were found to be eligible for the study (31 women used more than one preparation concomitantly, 24 women took more than one tablet per day, 11 women reported chronic gastrointestinal symptoms prior to pregnancy). Mean maternal age was 30 ± 4.7 years and nulliparity rate was 21.3%. There were no differences between the women in the various preparations groups with regard to mean maternal age (range 28.3–32.9 years, P = 0.31), nulliparity rate (range 16.1–29.2%, P = 0.46), and country of origin (P = 0.28). Most of the women (n = 358, 79.1%) used iron supplementation continuously during pregnancy, whereas the remaining used it only intermittently.

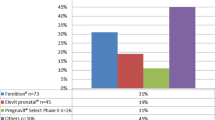

The most commonly used preparation was ferrous fumarate (46.8%, P < 0.01), either as an independent drug (38.4%) or in the form of multivitamin preparation (8.4%), followed by ferrous sulfate (31.8%; 11.9% as an immediate-release preparation, 19.9% as a slow-release preparation), ferric polymaltose (12.4%) and ferric bisglycinate (7.3%) (Table 1).

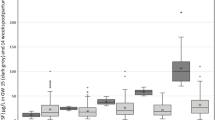

Overall, 45.0% of the participants reported at least one adverse effect related to the iron preparation. The most common complaint was constipation (27.4%, P < 0.01) (Table 1). Dark stool was reported by 28.3%, but was not considered an adverse effect for analysis purposes.

Multivitamin preparations and ferric bisglycinate were associated with significantly fewer side effects than the other preparations (23.7 and 21.2%, respectively, P < 0.01), and ferrous fumarate (as a separate preparation) and immediate-release ferrous sulfate were associated with the highest rate of side effects (56.3 and 53.7%, respectively). Constipation, the most common adverse affect, was reported less often by women taking multivitamin preparations (10.5%).

Overall, 83 (18.3%) women discontinued or changed their originally prescribed iron preparation. In almost all these cases (89%), the reason was side effects; in the remaining, the reasons were almost equally divided among price, ineffectiveness in preventing or correcting anemia and the lack of need for iron supplementation. Discontinuation rates were lowest for the multivitamin and ferric-bisglycinate preparations (10.5, 9.1%, respectively), and they dropped even further when analyzing discontinuation rates due to side effects alone (0.0, 6.1% respectively, P < 0.05). Moreover, while for most of the preparations the main reason for discontinuation was the associated side effects (66–97%), in the case of the multivitamin preparations, discontinuation was related mainly (75% of cases) to its ineffectiveness as an exclusive iron supplementation agent.

Regarding the choice of specific preparations, 58% of the women were unaware that there may be differences among the various preparations. In the remaining 42%, the preparation was recommended by the women’s physician (76%, P < 0.01), friends (15%), nurse (6%), or pharmacist (3%). Ferrous fumarate was recommended most often (25%, P < 0.05), and mostly by physicians (79%). The women reported that the main reasons given by the physicians for recommending this preparation were its effectiveness (48%) and low rate of side effects (45%). Ferric polymaltose was recommended in 14% of the cases, and slow-release ferrous sulfate in 15%. Ferric bisglycinate, being recommended for in 6% of these cases, was mainly recommended by the women’s friends (73%) owing to its low rate of side effects; in the other 27% of cases it was recommended by the physician.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the currently available preparations for iron supplementation during pregnancy in terms of frequency of use, rate of side effects and discontinuation rate.

We found that 84.5% of the women interviewed reported using iron supplementation, and of the women included in the study, 79.1% used it continuously during pregnancy. These results reflect a relatively high compliance compared with compliance rates reported by others [9–11]. It should be noted, however, that our findings were obtained in a group of women who gave birth in a single tertiary medical center, and may not reflect the compliance rates for iron supplementation in the general population of pregnant women.

Ferrous sulfate is the most widely used iron preparation throughout the world [12, 13]. In our study, ferrous sulfate and ferrous fumarate together accounted for 78% of iron supplement use. However, despite their efficacy and low cost, these preparations were associated with high rate of side effects, mainly of the gastrointestinal system, leading to poor compliance. Controlled-release ferrous sulfate preparations were reported to be associated with fewer upper-gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and epigastric discomfort [14, 15], although with no difference in discontinuation rates from conventional ferrous sulfate preparations. Others reported relatively better tolerability for polysaccharide-iron complexes [16] and iron bisglycinate [17] than the conventional ferrous sulfate preparations.

Almost half of the women in our study reported having side effects related to the iron supplements. Obviously, the assessment of gastrointestinal side effects in pregnant women poses a great difficulty because many of the complaints may be related to the pregnancy itself. For example, constipation and nausea, the most common side effects in our study (27.4, 10.8%, respectively), are also the most common gastrointestinal complaints among pregnant women unrelated to iron supplementation. Nevertheless, all the women in the study specifically attributed the symptoms to the iron preparations, and eventually, it is this subjective feeling that would affect compliance.

In our study, ferric bisglycinate caused the lowest rate of side effects. Nevertheless, considering the lower bioavailability of ferric compounds compared with ferrous salts [18, 19], it is possible that this difference in the rate of side effects will not be observed when equivalent effective doses of ferric and ferrous salts are used. Similarly, the multivitamin preparations, although containing ferrous fumarate as well, had a significantly lower rate of side effects than ferrous fumarate alone. This finding may be related to the presence of only 60 mg elemental iron in the multivitamin preparations compared with 100 mg in the conventional ferrous fumarate preparations.

The general incidence of constipation during pregnancy is about 30%, depending on dietary fiber intake [20, 21]; rates are highest in the first and third trimesters. In out study, 27.4% of the women reported iron supplement-related constipation. We speculate that, considering the high compliance rate of iron supplementation, iron may considerably contribute to this common complaint in pregnancy. Nausea is an even more common gastrointestinal symptom, occurring in 50–90% of pregnant women [22–24], mainly during the first trimester. Nevertheless, it was reported as an iron-related side effect in only 10.8% of the women in our study. It was the most common upper gastrointestinal complaint, with dyspepsia and vomiting occurring much less frequently. Nausea was less common in the women who took controlled-release ferrous sulfate (4.4%) or polysaccharide-iron complexes (3.6%), as suggested previously by others [14–16]. Further analysis of the contribution of the different side effects to discontinuation of iron supplementation revealed that vomiting was associated with almost 50% discontinuation rate, whereas the other adverse effects were better tolerated and were associated with similar discontinuation rates.

Unsurprisingly, in most cases (76%) the preparation used was recommended by the women’s physician. This finding, taken together with the fact that 58% of the women reported being unaware of any differences among the various preparations, highlights the critical role of the physician in determining compliance to iron supplementation. We believe that women should be informed about the possible side effects associated with the iron preparations, and that the importance of continuous iron supplementation throughout pregnancy, despite minor side effects, should be emphasized. Moreover, women should be informed regarding the availability of alternative preparations which may be better tolerated.

Our data demonstrate that some iron supplement preparations used in pregnancy may be associated with a lower rate of side effects than others. Randomized controlled studies evaluating the side effects and comparing the efficacy of these preparations are needed before any of these preparations can be routinely recommended as first-line treatment. Furthermore, alternative regimens of iron supplementation in terms of frequency [25] or dosage [26] have been suggested as an approach for increasing compliance, and their efficacy and tolerability should be evaluated as well.

References

World Health Organization (1992) The prevalence of anaemia in women: a tabulation of available information. WHO, Geneva

Macgregor M (1963) Maternal anaemia as a factor in prematurity and perinatal mortality. Scott Med J 8:134

Scholl TO, Hediger ML (1994) Anemia and iron-deficiency anemia: compilation of data on pregnancy outcome (discussion 500S–501S). Am J Clin Nutr 59(2 Suppl):492S–500S

Levy A, Fraser D, Katz M, Mazor M, Sheiner E (2005) Maternal anemia during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for low birthweight and preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 122(2):182–186

Stoltzfus RD, Dreyfuss ML (2000) Guidelines for the use of iron supplements to prevent and treat iron deficiency anemia. International Nutritional Anemia Consultative Group (INACG)

Pena-Rosas JP, Viteri FE (2006) Effects of routine oral iron supplementation with or without folic acid for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD004736

Casanueva E, Viteri FE, Mares-Galindo M, Meza-Camacho C, Loria A, Schnaas L et al (2006) Weekly iron as a safe alternative to daily supplementation for nonanemic pregnant women. Arch Med Res 37(5):674–682

Hemminki E, Merilainen J (1995) Long-term follow-up of mothers and their infants in a randomized trial on iron prophylaxis during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173(1):205–209

Schultink W, van der Ree M, Matulessi P, Gross R (1993) Low compliance with an iron-supplementation program: a study among pregnant women in Jakarta, Indonesia. Am J Clin Nutr 57(2):135–139

Nordeng H, Eskild A, Nesheim BI, Aursnes I, Jacobsen G (2003) Guidelines for iron supplementation in pregnancy: compliance among 431 parous Scandinavian women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 59(2):163–168

Yu SM, Keppel KG, Singh GK, Kessel W (1996) Preconceptional and prenatal multivitamin-mineral supplement use in the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Am J Public Health 86(2):240–242

DeMaeyer EM, Dallman P, Gumey JM, Hallberg L, Sood SK, Srikantia SG (1989) Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anaemia through primary health care. WHO, Geneva

Hansen CM (1994) Oral iron supplements. Am Pharm NS34(3):66–71

Rybo G, Solvell L (1971) Side-effect studies on a new sustained release iron preparation. Scand J Haematol 8(4):257–264

Brock C, Curry H, Hanna C, Knipfer M, Taylor L (1985) Adverse effects of iron supplementation: a comparative trial of a wax-matrix iron preparation and conventional ferrous sulfate tablets. Clin Ther 7(5):568–573

Jacobs P, Wood L, Bird AR (2000) Erythrocytes: better tolerance of iron polymaltose complex compared with ferrous sulphate in the treatment of anaemia. Hematol 5(1):77–83

Pineda O, Ashmead HD (2001) Effectiveness of treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children with ferrous bis-glycinate chelate. Nutrition 17(5):381–384

Jacobs P, Fransman D, Coghlan P (1993) Comparative bioavailability of ferric polymaltose and ferrous sulphate in iron-deficient blood donors. J Clin Apher 8(2):89–95

Bezkorovainy A (1989) Biochemistry of nonheme iron in man. II. Absorption of iron. Clin Physiol Biochem 7(2):53–69

Everson GT (1992) Gastrointestinal motility in pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 21(4):751–76

Greenhalf JO, Leonard HS (1973) Laxatives in the treatment of constipation in pregnant and breast-feeding mothers. Practitioner 210(256):259–263

Klebanoff MA, Koslowe PA, Kaslow R, Rhoads GG (1985) Epidemiology of vomiting in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 66(5):612–616

FitzGerald CM (1984) Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Br J Med Psychol 57(Pt 2):159–165

Tierson FD, Olsen CL, Hook EB (1986) Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and association with pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 155(5):1017–1022

Hyder SM, Persson LA, Chowdhury AM, Ekstrom EC (2002) Do side-effects reduce compliance to iron supplementation? A study of daily- and weekly-dose regimens in pregnancy. J Health Popul Nutr 20(2):175–179

Makrides M, Crowther CA, Gibson RA, Gibson RS, Skeaff CM (2003) Efficacy and tolerability of low-dose iron supplements during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 78(1):145–153

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Melamed, N., Ben-Haroush, A., Kaplan, B. et al. Iron supplementation in pregnancy—does the preparation matter?. Arch Gynecol Obstet 276, 601–604 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-007-0388-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-007-0388-3