Abstract

Discretized landscapes can be mapped onto ranked surfaces, where every element (site or bond) has a unique rank associated with its corresponding relative height. By sequentially allocating these elements according to their ranks and systematically preventing the occupation of bridges, namely elements that, if occupied, would provide global connectivity, we disclose that bridges hide a new tricritical point at an occupation fraction p = pc, where pc is the percolation threshold of random percolation. For any value of p in the interval pc < p ≤ 1, our results show that the set of bridges has a fractal dimension dBB ≈ 1.22 in two dimensions. In the limit p → 1, a self-similar fracture is revealed as a singly connected line that divides the system in two domains. We then unveil how several seemingly unrelated physical models tumble into the same universality class and also present results for higher dimensions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Any real landscape can be duly coarse-grained and represented as a two-dimensional discretized map of regular cells (e.g., a square lattice of sites or bonds) to which average heights can be associated. This process is exemplarily shown in Figs. 1(a)–(c). As such, the concept of discretized maps has been considered as a way to delimit spatial boundaries in a wide range of seemingly unrelated problems, ranging from tracing water basins and river networks in landscapes1,2,3,4,5 to the identification of cancerous cells in human tissues6,7 and the study of spatial competition in multispecies ecosystems8,9. Moreover, previous studies have shown that cracks or surviving paths through discretized maps possess a universal fractal dimension which can be physically realized in terms of optimal paths under strong disorder10,11,12,13, optimal path cracks14,15, loopless percolation16,17, or minimum spanning trees18,19,20,21,22,23. Here we show that all these problems can be understood in terms of the same universal concept of fracturing a ranked surface.

The generation process of a ranked surface.

The landscape in (a) is coarse-grained to the low-resolution system of 8 × 8 shown in (b) and then represented as a discretized map of local heights, as depicted in (c). By ranking these heights in crescent order, one obtains the ranked surface in (d). In fact, the landscape shown in (a) is a high resolution synthetic map obtained from a fractional Brownian motion simulation based on the Fourier filtering method15,41,42,43,44,45,46.

We start by defining a ranked surface. Given a two-dimensional discretized map of size L × L, we generate a list containing the heights of its elements (sites or bonds) in crescent order and then replace the numerical values in the original map by their corresponding ranks. As depicted in Fig. 1(d), the result is a ranked surface. The process of fracture generation is rather simple. Once the ranked surface is obtained, we sequentially occupy the elements of an empty lattice with the same size following the crescent rank order of the corresponding elements (i.e., in the same position) on the ranked surface. During each step of the allocation process, only bridges, identified as those lattice elements which, once occupied, would create a spanning cluster (i.e., a globally connecting cluster)24, are never occupied. These elements will eventually form a macroscopic fracture.

In Fig. 2 we show the evolution of the fracture line on a large ranked surface with the fraction of occupied bonds p. As displayed, the lattice is initially seeded by a set of disconnected bridge elements at low values of p, while for p → 1 the fracture finally emerges towards a singly connected line that divides the system in two. As we show later in this article, our results reveal that this line is fractal with dimension dBB ≈ 1.22. Interestingly, this value is statistically identical to the dimensions of fractures generated from different models previously investigated10,11,12,13. However, at the percolation threshold value of the classical random percolation model24,25, p = pc, the set of bridge bonds appearing in any configuration of our model should be identical to the set of the so-called anti-red bonds in random percolation26. As first proposed by Coniglio26 and numerically verified by Scholder27, at p = pc, this set is also fractal, but with dimension 1/ν ( = 3/4 in 2D), where ν is the correlation length exponent.

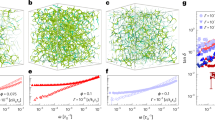

Snapshots of the fractal set of bridges in two (line) and three (surface) dimensions.

For 2D four stages are seen (from left to right): p = pc (black), p = 1.01pc (blue), p = 1.05pc (green) and p = 1 (red), while for 3D only the final set is shown. We considered in 2D a square lattice with 10242 sites and, in 3D, a simple-cubic lattice with 5123 sites. The fractal dimension is dBB = 1.215 ± 0.003, in 2D and dBB = 2.50 ± 0.02, in 3D.

Motivated by this substantial change in the fractal behavior at distinct stages of our fracturing process, in what follows we address how the set of bridges scales with the fraction of occupied bonds and the system size at p = pc analogously to a theta point28,29,30, while for all values of p above pc, it has a fractal dimension dBB. Moreover, we introduce a new tricritical crossover exponent, which we study up to dimension six, the upper-critical dimension of percolation.

Results

We performed simulations of fracturing ranked surfaces on square lattices. It is worth noting that, despite the similarities with random percolation, the suppressing of connectivity poses a statistically different problem. For example, while for p → 1 there is only a single configuration in random percolation (all bonds occupied), in ranked percolation there are N!, evenly weighted, possible configurations, where N is the total number of bonds. In classical percolation the total number of configurations is 2N. Figure 3 shows the dependence of the number of bridge bonds NBB on system size, for different fractions of occupied bonds, namely, p = pc = 0.5, p = 0.51 and p = 0.8. As expected, at the percolation threshold of classical percolation (p = pc), the number of bridge bonds diverges with system size as NBB ~ L1/ν, where ν is the correlation length exponent, with ν = 4/3 in 2D; while for p = 0.8,  , with dBB = 1.215 ± 0.003. The latter is in fact observed at any p > pc. We found the same result (see

Supplementary Information

) for site percolation and on other lattices (star, triangular and honeycomb), which provides strong evidence for the universality of this exponent. For

, with dBB = 1.215 ± 0.003. The latter is in fact observed at any p > pc. We found the same result (see

Supplementary Information

) for site percolation and on other lattices (star, triangular and honeycomb), which provides strong evidence for the universality of this exponent. For  , like p = 0.51 we can observe, as depicted in Fig. 3, a crossover between the two different regimes. The inset of Fig. 4 shows NBB, rescaled by

, like p = 0.51 we can observe, as depicted in Fig. 3, a crossover between the two different regimes. The inset of Fig. 4 shows NBB, rescaled by  , as a function of p, for different system sizes. The number of bridge bonds grows with p, such that, NBB ~ (p − pc)ζ, where ζ = 0.50 ± 0.03 is a novel exponent, which we call bridge-growth exponent. The overlap of the different curves confirms that the fractal dimension of the bridge bonds above pc is dBB, for all p > pc. This result differs from classical percolation where fractality is solely observed at criticality24,25 while, above pc, bridge bonds are only observed for finite systems26.

, as a function of p, for different system sizes. The number of bridge bonds grows with p, such that, NBB ~ (p − pc)ζ, where ζ = 0.50 ± 0.03 is a novel exponent, which we call bridge-growth exponent. The overlap of the different curves confirms that the fractal dimension of the bridge bonds above pc is dBB, for all p > pc. This result differs from classical percolation where fractality is solely observed at criticality24,25 while, above pc, bridge bonds are only observed for finite systems26.

Crossover in the size dependence.

Number of bridge bonds, NBB, for different p, namely, p = pc = 0.5 (circles), p = 0.51 (stars) and p = 0.8 (triangles). The solid lines stand for the best fit. At p = pc, as conjectured by Coniglio26, NBB ~ L1/ν, where ν = 4/3 is the critical exponent of the correlation length in 2D. For p > pc, the number of bridge bonds scales with  . A crossover between the two regimes in system size is observed (stars) for p in the neighborhood of pc. Systems of size L2 have been considered, with L ranging from 32 to 4096. All results have been averaged over 104 samples. Error bars are smaller than the symbol size.

. A crossover between the two regimes in system size is observed (stars) for p in the neighborhood of pc. Systems of size L2 have been considered, with L ranging from 32 to 4096. All results have been averaged over 104 samples. Error bars are smaller than the symbol size.

Tricritical scaling, crossover and data collapse.

Number of bridge bonds, NBB, as a function of the fraction of occupied bonds, p, for 2D with different system sizes L = {256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096}. The scaling function given by equation (1) is applied, with θ = 0.93, obtaining ζ = 0.50 ± 0.03. In the inset, NBB has been rescaled by  , where dBB = 1.215. All results have been averaged over 104 samples.

, where dBB = 1.215. All results have been averaged over 104 samples.

For polymer chains, at high temperatures, the excluded volume prevails over attractive forces and the chain can be described as a self-avoiding walk. When the temperature is reduced, the attractive forces become relevant leading, at a theta-temperature, to a new exponent at the crossover between two dimensions28,29,30. Analogously, in ranked percolation the fractal dimension of the bridge bonds is 1/ν, at p = pc, between dBB above pc and zero below pc. For the tricritical scaling we verify the following ansatz,

where  for x ≠ 0 and is nonzero at x = 0; and the exponent θ is the crossover exponent. Therefore, the following relation is obtained,

for x ≠ 0 and is nonzero at x = 0; and the exponent θ is the crossover exponent. Therefore, the following relation is obtained,

where φ = d − dBB. In the main plot of Fig. 4 we see, for 2D, the scaling given by equation (1), with θ = 0.93.

The results above disclose a tricritical pc below which the fraction of bridges in the bridge line vanishes in the thermodynamic limit. This is identical to a minimum height in the bridge line, H = hmin, in the context of landscapes (Figs. 1(a)–(b)). For a cumulative distribution function of heights H, P(H ≤ h), the minimum is given by P(H ≤ hmin) = pc. Note that, for uncorrelated landscapes, regardless the distribution of heights, the set of bridges only depends on their position in the rank. To observe the new set of exponents on discretized landscapes (Fig. 1(c)), NBB is the number of sites in the bridge line with both neighbors (one at each side) having height lower than h, where P(H ≤ h) = p.

To study the dependence of exponents ζ and φ on the spatial dimension, we analyze the same problem up to dimension six. On a simple-cubic lattice (3D), above pc, the set of all bridge bonds has a fractal dimension dBB = 2.50 ± 0.05 and grows with ζ = 1.0 ± 0.1 (see Supplementary Information ). Figure 5 shows the size dependence of NBB, in the limit p = 1, for lattices with size Ld, where 2 ≤ d ≤ 6 is the spatial dimension. In the inset, we plot the exponent φ as a function of d. Since the set of bridge bonds blocks connectivity from one side to the other, its fractal dimension must follow d − 1 ≤ dBB ≤ d, i.e., 0 ≤ φ ≤ 1. With increasing dimension φ decreases. At the upper-critical dimension of percolation, dc = 6, φ = 0.0 ± 0.1 and the set of bridge bonds becomes dense having the spatial dimension d. Table I summarizes the exponents for dimensions 2 to 6. The bridge-growth exponent grows with d and converges to ζ = 1.5 ± 0.7 at the upper-critical dimension. For d > 6, above the critical dimension of percolation, the exponent φ remains zero and the dimension of the set of bridges is equal to d. This can be understood from the fact that above dc one has an infinity of spanning clusters31 and thus many more possible bridges. Since the dimension of the set of bridges at p = pc is 1/ν and above pc is d, the crossover exponent increases with d, with the relation given by equation (2), where φ = 0.

Dependence on the spatial dimension and approach to the mean-field limit.

Size dependence of the number of bridge bonds, NBB, in the limit p = 1, up to dimension six. The solid lines stand for the best fit. The mass of the shortest path in loopless percolation (SP) in 2D is also included for comparison. Results have been averaged over 104 samples for 2D and 3D and 102 samples for higher dimensions. Error bars are smaller than the symbol size. The inset shows the dependence on the spatial dimension of the exponent φ. At the upper-critical dimension of percolation, d = 6, the set of bridge bonds becomes dense having the spatial dimension.

Since one can interchange occupied and empty bonds, there exists a symmetry between bridges and cutting bonds (red bonds), so one can raise the question of what happens when bonds are removed from a percolating system with the constraint that connectivity cannot be broken. Initially all bonds are occupied and at the end, since cutting bonds are never removed, a line of cutting bonds is obtained, which we denote here as the cutting line. Above pc, as in the classical case, the percolation cluster is compact and there are no cutting bonds. For p < pc, the set of cutting bonds is fractal with the same fractal dimension as the bridge-bond set, dCB = dBB, whereas at pc it is 1/ν. For the crossover scaling a similar ansatz to the one given by equation (1) is verified, where the argument of the scaling function is then (pc − p)Lθ. The same hyperscaling of equation (2) is obtained with φ = d − dCB. At d = 2, our numerical results corroborate the hypothesis of the same ζ and φ, for cutting and bridge bonds (see Supplementary Information ). For d > 2, the set of cutting bonds is a line with dCB ≤ 2 and the one of bridge bonds has a dimension above d − 1, so that the fractal dimensions differ. Above the critical dimension, the set of cutting bonds has dimension two, like the shortest path at pc32, for any p ≤ pc. Fisher33 proposed a bond-site transformation to map bond percolation on a lattice onto site percolation on a covering graph. For example, the covering graph of the square lattice is obtained by adding all diagonal edges to every other face34. Considering such a mapping for ranked percolation and, following the analogy with a random landscape, where sites are sequentially removed from the lowest number (height) and suppressing global disconnection, the obtained cutting line is identical to the bridge one with the constraint applied in the perpendicular direction. The same is also observed for site-ranked percolation on a square lattice. Given the relation between connectivity and disconnection, in both cases, the cutting version needs to be defined on different topologies, namely, the star lattice for the square (on sites) and the same lattice for its covering graph, but with swapped cells of diagonal bonds. For the triangular lattice, the relation between cutting and bridges sites is straightforward without requiring additional connections.

Discussion

For several different models in 2D the same fractal dimension as the one of bridge bonds has been reported. Here we discuss how some of them can be related with the process of fracturing ranked surfaces. Let us construct ranked percolation configurations on a random landscape starting with the bond with the largest number (height) and then occupying bonds sequentially in order of decreasing number. Each time a chosen bond closes a loop, it is not occupied (loopless). One stops the procedure when, for the first time, a path of connected sites spans from one side to the other (percolation threshold). Since all clusters are trees, the backbone and the shortest path are the same and their fractal dimension is identical to the bridge-bond line, as verified in Fig. 5. In fact, given the connectivity/disconnection relation discussed in the previous section, this line corresponds to the bridge line when bonds are occupied from the lowest to the largest number in the covering graph. This line also corresponds to the line of cutting bonds when bonds are removed from the smallest to the largest number. A similar procedure was also proposed to obtain the minimum spanning tree (MST), for which the same fractal dimension is found for the paths between all pairs of sites19. There bonds are sequentially removed (from the highest to the lowest value) under the constraint that all sites remain connected. If the constraint is relaxed such that only connectivity between two opposite borders is imposed, the cutting-bond line is obtained. Therefore, the cutting-bond line is the path between borders on the MST for which the largest value (height) is minimum, a valid relation in any spatial dimension d.

The fractal dimension dBB was also observed for the backbone of the optimal path crack (OPC)14,15. For a random landscape, the sequence of optimal paths between opposite borders is obtained and their highest site removed. Every such path crosses the bridge line. The highest site on successive paths is either on the bridge line itself or is higher than the lowest bridge-line site. Therefore, as in the loopless percolation described before, the removed sites percolate when all sites on the bridge line are removed, which is the backbone of the crack, giving the same fractal dimension dBB. This is in fact the case for the crack of any sequence of self-avoiding paths between opposite borders. Since in this case the duality between cutting and bridges is not used (only valid in 2D), the relation between OPC and bridge bonds is still true in higher dimensions.

Let us now define the optimal minimax path (OMP) in the following way. One starts selecting the set of paths on the landscape for which the highest-ranked site is minimum (minimax paths). Such set is then reduced to include only the paths for which the second highest site is also minimum and one proceeds iteratively to the following sites, until a unique path is obtained. This path is the optimal path in strong disorder16,17, since under such disorder strength each site is higher than the sum over the height of all sites with lower rank. This path is also identical to the backbone of the loopless-ranked-percolation cluster when occupied from the lowest to the largest number and, therefore, the cutting line in any dimension.

In summary, suppressing connectivity (disconnection) between opposite borders on ranked surfaces leads to a fractal set of bridge (cutting) bonds, with a universal fractal dimension, even far away from the critical point of classical percolation. In 2D, there is an equivalence between bridges and cutting bonds and dBB = dCB, whereas for d > 2 cutting bonds are still a fractal line but bridge bonds form a surface. The discussed models are then split into two groups. The ones suppressing connectivity (e.g., watershed10,12 and optimal path crack14,15) are in the bridges universality class, while the ones keeping connectivity (e.g., optimal path on the MST or in strong disorder media16) are in the universality class of cutting bonds. For d > 6, dBB = d and dCB = 2, so we conjecture that the upper-critical dimension of bridges and cutting bonds is also dc = 6. Finally, we show that, at the percolation threshold of classical percolation, ranked percolation displays a theta-point-like crossover.

This work opens up several challenges. Besides the need for a more precise numerical estimation of the bridge-growth exponent, it would be interesting to formulate a renormalization group scheme and to obtain the new set of exponents from analytic treatments such as, e.g., exact results in the mean-field limit and a Schramm-Loewner evolution in two dimensions. Another interesting possibility is to find the corresponding exponents in other related problems with different universality classes like, e.g., the Kasteleyn-Fortuin clusters in the q-state Potts model26,35,36,37,38 with or without magnetic field. Regarding the fractal dimension of the surface of discontinuous percolation clusters39,40, it would also be interesting to understand how it relates with the herein introduced bridge-bonds universality class. For the cutting bonds, the study of the crossover for higher dimensions represents another computational challenge. Finally, it would also be interesting to try to identify the third scaling field of our theta-like point.

Methods

All numerical results have been obtained with Monte Carlo simulations. Results have been averaged over 104 samples for 2D and 3D and 102 samples for higher dimensions.

References

Stark, C. P. An invasion percolation model of drainage network evolution. Nature 352, 423–425 (1991).

Maritan, A., Colaiori, F., Flammini, A., Cieplak, M. & Banavar, J. R. Universality classes of optimal channel networks. Science 272, 984–986 (1996).

Manna, S. S. & Subramanian, B. Quasirandom spanning tree model for the early river network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3460–3463 (1996).

Knecht, C. L., Trump, W., ben-Avraham, D. & Ziff, R. M. Retention capacity of random surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 045703 (2012).

Baek, S. K. & Kim, B. J. Critical condition of the water-retention model. arXiv:1111.0425.

Yan, J., Zhao, B., Wang, L., Zelenetz, A. & Schwartz, L. H. Marker-controlled watershed for lymphoma segmentation in sequential CT images. Med. Phys. 33, 2452–2460 (2006).

Ikedo, Y. et al. Development of a fully automatic scheme for detection of masses in whole breast ultrasound images. Med. Phys. 34, 4378–4388 (2007).

Kerr, B., Neuhauser, C., Bohannan, B. J. M. & Dean, A. M. Local migration promotes competitive restraint in a host-pathogen ’tragedy of the commons’. Nature 442, 75–78 (2006).

Mathiesen, J., Mitarai, N., Sneppen, K. & Trusina, A. Ecosystems with mutually exclusive interactions self-organize to a state of high diversity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 188101 (2011).

Cieplak, M., Maritan, A. & Banavar, J. R. Optimal paths and domain walls in the strong disorder limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 2320–2323 (1994).

Cieplak, M., Maritan, A. & Banavar, J. R. Invasion percolation and Eden growth: geometry and universality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3754–3757 (1996).

Fehr, E. et al. New efficient methods for calculating watersheds. J. Stat. Mech. P09007 (2009).

Fehr, E., Kadau, D., Andrade Jr, J. S. & Herrmann, H. J. Impact of perturbations on watersheds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 048501 (2011).

Andrade Jr, J. S., Oliveira, E. A., Moreira, A. A. & Herrmann, H. J. Fracturing the optimal paths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 225503 (2009).

Oliveira, E. A., Schrenk, K. J., Araújo, N. A. M., Herrmann, H. J. & Andrade Jr, J. S. Optimal-path cracks in correlated and uncorrelated lattices. Phys. Rev. E 83, 046113 (2011).

Porto, M., Havlin, S., Schwarzer, S. & Bunde, A. Optimal path in strong disorder and shortest path in invasion percolation with trapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 4060–4062 (1997).

Porto, M., Schwartz, N., Havlin, S. & Bunde, A. Optimal paths in disordered media: scaling of the crossover from self-similar to self-affine behavior. Phys. Rev. E 60, R2448–R2451 (1999).

Barabási, A.-L. Invasion percolation and global optimization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3750–3753 (1996).

Dobrin, R. & Duxbury, P. M. Minimum spanning trees on random networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5076–5079 (2001).

Jackson, T. S. & Read, N. Theory of minimum spanning trees. I. Mean-field theory and strongly disordered spin-glass model. Phys. Rev. E 81, 021130 (2010).

Çiftçi, K. Minimum spanning tree reflects the alterations of the default mode network during Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 39, 1493–1504 (2011).

Goyal, S. & Puri, R. K. Formation of fragments in heavy-ion collisions using a modified clusterization method. Phys. Rev. C 83, 047601 (2011).

Hubbe, M., Harvati, K. & Neves, W. Paleoamerican morphology in the context of European and East Asian Late Pleistocene variation: implications for human dispersion into the New World. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 144, 442–453 (2011).

Stauffer, D. & Aharony, A. Introduction to Percolation Theory (Taylor and Francis, 1994).

Broadbent, S. R. & Hammersley, J. M. Percolation processes: I. Crystals and mazes. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 53, 629–641 (1957).

Coniglio, A. Fractal structure of Ising and Potts clusters: exact results. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 3054–3057 (1989).

Scholder, O. Anti-red bond calculation algorithm in percolation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 20, 267–272 (2009).

de Gennes, P.-G. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics (Cornell Univ. Press, 1979).

Chang, I. & Aharony, A. Flory approximation for self-avoiding walks near the theta-point on fractal structures. J. Phys. I 1, 313–316 (1991).

Poole, P. H., Coniglio, A., Jan, N. & Stanley, H. E. Universality classes of the θ and θ′ points. Phys. Rev. B 39, 495–504 (1989).

Newman, C. M. & Schulman, L. S. Infinite clusters in percolation models. J. Stat. Phys. 26, 613–628 (1981).

Havlin, S. & Nossal, R. Topological properties of percolation clusters. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 17, L427–L432 (1984).

Fisher, M. E. Critical probabilities for cluster size and percolation problems. J. Math. Phys. 2, 620–627 (1961).

Wierman, J. C. Substitution method critical probability bounds for the square lattice site percolation model. Comb. Probab. Comput. 4, 181–188 (1995).

Fortuin, C. M. & Kasteleyn, P. W. On the random-cluster model: I. Introduction and relation to other models. Physica 57, 536–564 (1972).

Wu, F. Y. Percolation and the Potts model. J. Stat. Phys. 18, 115–123 (1978).

Coniglio, A. & Klein, W. Clusters and Ising critical droplets: a renormalisation group approach. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 13, 2775–2780 (1980).

Deng, Y., Blöte, H. W. J. & Nienhuis, B. Geometric properties of two-dimensional critical and tricritical Potts models. Phys. Rev. E 69, 026123 (2004).

Araújo, N. A. M. & Herrmann, H. J. Explosive percolation via control of the largest cluster. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 035701 (2010).

Schrenk, K. J., Araújo, N. A. M. & Herrmann, H. J. Gaussian model of explosive percolation in three and higher dimensions. Phys. Rev. E 84, 041136 (2011).

Prakash, S., Havlin, S., Schwartz, M. & Stanley, H. E. Structural and dynamical properties of long-range correlated percolation. Phys. Rev. A 46, R1724–R1727 (1992).

Sahimi, M. Long-range correlated percolation and flow and transport in heterogeneous porous media. J. Phys. I France 4, 1263–1268 (1994).

Sahimi, M. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Scaling properties of a percolation model with long-range correlations. Phys. Rev. E 54, 3870–3880 (1996).

Makse, H. A., Havlin, S., Schwartz, M. & Stanley, H. E. Method for generating long-range correlations for large systems. Phys. Rev. E 53, 5445–5449 (1996).

The Science of Fractal Images, edited by Peitgen H., & Saupe D. (Springer, 1988).

Mandelbrot, B. B. & Van Ness, J. W. Fractional Brownian motions, fractional noises and applications. SIAM Rev. 10, 422–437 (1968).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the ETH Risk Center. We also acknowledge the Brazilian agencies CNPq, CAPES and FUNCAP and the Pronex grant CNPq/FUNCAP, for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.S. and N.A.M.A. carried out the numerical experiments. All authors conceived and designed the research, analyzed the data, worked out the theory and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Schrenk, K., Araújo, N., Andrade Jr, J. et al. Fracturing ranked surfaces. Sci Rep 2, 348 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00348

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00348

This article is cited by

-

A universal approach for drainage basins

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Schramm-Loewner evolution and perimeter of percolation clusters of correlated random landscapes

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

A comparison of hydrological and topological watersheds

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Abnormal grain growth mediated by fractal boundary migration at the nanoscale

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

The influence of statistical properties of Fourier coefficients on random Gaussian surfaces

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.